Adaptation and the Australian Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bruce Beresford's Breaker Morant Re-Viewed

FILMHISTORIA Online Vol. 30, núm. 1 (2020) · ISSN: 2014-668X The Boers and the Breaker: Bruce Beresford’s Breaker Morant Re-Viewed ROBERT J. CARDULLO University of Michigan Abstract This essay is a re-viewing of Breaker Morant in the contexts of New Australian Cinema, the Boer War, Australian Federation, the genre of the military courtroom drama, and the directing career of Bruce Beresford. The author argues that the film is no simple platitudinous melodrama about military injustice—as it is still widely regarded by many—but instead a sterling dramatization of one of the most controversial episodes in Australian colonial history. The author argues, further, that Breaker Morant is also a sterling instance of “telescoping,” in which the film’s action, set in the past, is intended as a comment upon the world of the present—the present in this case being that of a twentieth-century guerrilla war known as the Vietnam “conflict.” Keywords: Breaker Morant; Bruce Beresford; New Australian Cinema; Boer War; Australian Federation; military courtroom drama. Resumen Este ensayo es una revisión del film Consejo de guerra (Breaker Morant, 1980) desde perspectivas como la del Nuevo Cine Australiano, la guerra de los boers, la Federación Australiana, el género del drama en una corte marcial y la trayectoria del realizador Bruce Beresford. El autor argumenta que la película no es un simple melodrama sobre la injusticia militar, como todavía es ampliamente considerado por muchos, sino una dramatización excelente de uno de los episodios más controvertidos en la historia colonial australiana. El director afirma, además, que Breaker Morant es también una excelente instancia de "telescopio", en el que la acción de la película, ambientada en el pasado, pretende ser una referencia al mundo del presente, en este caso es el de una guerra de guerrillas del siglo XX conocida como el "conflicto" de Vietnam. -

A Dark New World : Anatomy of Australian Horror Films

A dark new world: Anatomy of Australian horror films Mark David Ryan Faculty of Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the degree Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), December 2008 The Films (from top left to right): Undead (2003); Cut (2000); Wolf Creek (2005); Rogue (2007); Storm Warning (2006); Black Water (2007); Demons Among Us (2006); Gabriel (2007); Feed (2005). ii KEY WORDS Australian horror films; horror films; horror genre; movie genres; globalisation of film production; internationalisation; Australian film industry; independent film; fan culture iii ABSTRACT After experimental beginnings in the 1970s, a commercial push in the 1980s, and an underground existence in the 1990s, from 2000 to 2007 contemporary Australian horror production has experienced a period of strong growth and relative commercial success unequalled throughout the past three decades of Australian film history. This study explores the rise of contemporary Australian horror production: emerging production and distribution models; the films produced; and the industrial, market and technological forces driving production. Australian horror production is a vibrant production sector comprising mainstream and underground spheres of production. Mainstream horror production is an independent, internationally oriented production sector on the margins of the Australian film industry producing titles such as Wolf Creek (2005) and Rogue (2007), while underground production is a fan-based, indie filmmaking subculture, producing credit-card films such as I know How Many Runs You Scored Last Summer (2006) and The Killbillies (2002). Overlap between these spheres of production, results in ‘high-end indie’ films such as Undead (2003) and Gabriel (2007) emerging from the underground but crossing over into the mainstream. -

The Workshop Film Group – a History 1968 – 2018

The Workshop Film Group – A History 1968 – 2018 THE WORKSHOP FILM GROUP A History 1968 - 2018 By Richard Keys, John Lanser and Michael O’Rourke Dedicated to Vi & Laurie Collings and Helen Ramsay. With thanks to all of our members who have contributed so much over the journey. Clockwise from top left: Helen Ramsay, Vi Collings, Laurie Collings First published by the Workshop Film Group, 2018 Workshop Arts Centre, 33 Laurel St, Willoughby, NSW www.workshopfilmgroup.net Copyright © Richard Keys, John Lanser and Michael O’Rourke, 2018 Compiled by Ian Grey 16 July 2018 Printed and bound by Forestville Printing, E4/15 Narabang Way, Belrose, NSW 2085 Page | 1 The Workshop Film Group – A History 1968 – 2018 CONTENTS Background 3 Birth of a film society 4 Programming 5 Technical challenges and significant steps forward 6 Residential film weekends 7 Non-residential film weekends 10 The sound of silents 10 Another dollar, Another Day 12 The Group logo 13 Special guests 14 Committee and membership 19 Appendix 1. Filmography 21 Appendix 2. Milestones 22 Appendix 3. Press clippings 23 Appendix 4 Programs 29 Page | 2 The Workshop Film Group – A History 1968 – 2018 BACKGROUND The Workshop Arts Centre (WAC), established by the artist and teacher Joy Ewart, was officially opened by Australian artist Hal Missingham on August 16, 1963. Prior to this Joy had run an art studio in a two-storey building - a former stable with overhead loft - in Dalton Street, Chatswood. Classes were held there from 1955 until 1961 when the Willoughby Council declared the premises unfit for occupation. -

David Stratton's Stories of Australian Cinema

David Stratton’s Stories of Australian Cinema With thanks to the extraordinary filmmakers and actors who make these films possible. Presenter DAVID STRATTON Writer & Director SALLY AITKEN Producers JO-ANNE McGOWAN JENNIFER PEEDOM Executive Producer MANDY CHANG Director of Photography KEVIN SCOTT Editors ADRIAN ROSTIROLLA MARK MIDDIS KARIN STEININGER HILARY BALMOND Sound Design LIAM EGAN Composer CAITLIN YEO Line Producer JODI MADDOCKS Head of Arts MANDY CHANG Series Producer CLAUDE GONZALES Development Research & Writing ALEX BARRY Legals STEPHEN BOYLE SOPHIE GODDARD SC SALLY McCAUSLAND Production Manager JODIE PASSMORE Production Co-ordinator KATIE AMOS Researchers RACHEL ROBINSON CAMERON MANION Interview & Post Transcripts JESSICA IMMER Sound Recordists DAN MIAU LEO SULLIVAN DANE CODY NICK BATTERHAM Additional Photography JUDD OVERTON JUSTINE KERRIGAN STEPHEN STANDEN ASHLEIGH CARTER ROBB SHAW-VELZEN Drone Operators NICK ROBINSON JONATHAN HARDING Camera Assistants GERARD MAHER ROB TENCH MARK COLLINS DREW ENGLISH JOSHUA DANG SIMON WILLIAMS NICHOLAS EVERETT ANTHONY RILOCAPRO LUKE WHITMORE Hair & Makeup FERN MADDEN DIANE DUSTING NATALIE VINCETICH BELINDA MOORE Post Producers ALEX BARRY LISA MATTHEWS Assistant Editors WAYNE C BLAIR ANNIE ZHANG Archive Consultant MIRIAM KENTER Graphics Designer THE KINGDOM OF LUDD Production Accountant LEAH HALL Stills Photographers PETER ADAMS JAMIE BILLING MARIA BOYADGIS RAYMOND MAHER MARK ROGERS PETER TARASUIK Post Production Facility DEFINITION FILMS SYDNEY Head of Post Production DAVID GROSS Online Editor -

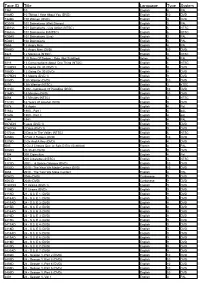

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

43E Festival International Du Film De La Rochelle Du 26 Juin Au 5 Juillet 2015 Le Puzzle Des Cinémas Du Monde

43e Festival International du Film de La Rochelle du 26 juin au 5 juillet 2015 LE PUZZLE DES CINÉMAS DU MONDE Une fois de plus nous revient l’impossible tâche de synthétiser une édition multiforme, tant par le nombre de films présentés que par les contextes dans lesquels ils ont été conçus. Nous ne pouvons nous résoudre à en sélectionner beaucoup moins, ce n’est pas faute d’essayer, et de toutes manières, un contexte économique plutôt inquiétant nous y contraint ; mais qu’une ou plusieurs pièces essentielles viennent à manquer au puzzle mental dont nous tentons, à l’année, de joindre les pièces irrégulières, et le Festival nous paraîtrait bancal. Finalement, ce qui rassemble tous ces films, qu’ils soient encore matériels ou virtuels (50/50), c’est nous, sélectionneuses au long cours. Nous souhaitons proposer aux spectateurs un panorama généreux de la chose filmique, cohérent, harmonieux, digne, sincère, quoique, la sincérité… Ambitieux aussi car nous aimons plus que tout les cinéastes qui prennent des risques et notre devise secrète pourrait bien être : mieux vaut un bon film raté qu’un mauvais film réussi. Et enfin, il nous plaît que les films se parlent, se rencontrent, s’éclairent les uns les autres et entrent en résonance dans l’esprit du festivalier. En 2015, nous avons procédé à un rééquilibrage géographique vers l’Asie, absente depuis plusieurs éditions de la programmation. Tout d’abord, avec le grand Hou Hsiao-hsien qui en est un digne représentant puisqu’il a tourné non seulement à Taïwan, son île natale mais aussi au Japon, à Hongkong et en Chine. -

Inclusive and Values Education Resources

INCLUSIVE AND VALUES EDUCATION RESOURCES Television, lm and multimedia have important roles to play in learning outcomes across the curriculum. The ACTF programs featured above can be used in multiple education settings to support the teaching of English, Arts (lm/media studies), Science, Technology, Indigenous education, Environment, HPE (personal development) and Values education. Each ACTF production is supported with teaching resources; either freely available online through the Learning Centre or on DVD ROM, purchased with the production. Visit the ACTF online catalogue at www.actf.com.au for the latest programs, teaching resources, lesson plans, teaching kits, CD and DVD materials. AUSTRALIAN CHILDREN’S TELEVISION FOUNDATION Level 3, 145 Smith Street Fitzroy | Victoria 3065 | AUSTRALIA ph: +61 3 9419 8800 | fx: +61 3 9419 0660 DATE TIME VENUE COST Friday 23rd October, 7.45pm for an The Plaza Ballroom, Regent Theatre Adult $75 + GST 2009 8.00pm start Collins Street, Melbourne Junior (under 15) $35 + GST Brought to you by Australian and New Zealand Cinema 8 Shortcuts TINA KAUFMAN 10 A Matter of Trust: Last Ride CARLY MILLAR 14 'Letting Things Breathe': Glendyn Ivin, Hugo Weaving and Tom Russell on Last Ride TOM REDWOOD 18 Tests of Endurance: Love, Faith and Family in My Year Without Sex ANNA ZAGALA 24 Swimming with Sharks: A Conversation with Sarah Watt DAVE HOSKIN 30 A Matter of Interpretation: Disgrace Documentary BRIAN MCFARLANE 36 The Birth of a Nation: Living on the Land in 76 Eyes on the World: Australian Documentary at Lucky -

A STUDY GUIDE by Katy Marriner

© ATOM 2012 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN 978-1-74295-267-3 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Raising the Curtain is a three-part television series celebrating the history of Australian theatre. ANDREW SAW, DIRECTOR ANDREW UPTON Commissioned by Studio, the series tells the story of how Australia has entertained and been entertained. From the entrepreneurial risk-takers that brought the first Australian plays to life, to the struggle to define an Australian voice on the worldwide stage, Raising the Curtain is an in-depth exploration of all that has JULIA PETERS, EXECUTIVE PRODUCER ALINE JACQUES, SERIES PRODUCER made Australian theatre what it is today. students undertaking Drama, English, » NEIL ARMFIELD is a director of Curriculum links History, Media and Theatre Studies. theatre, film and opera. He was appointed an Officer of the Order Studying theatre history and current In completing the tasks, students will of Australia for service to the arts, trends, allows students to engage have demonstrated the ability to: nationally and internationally, as a with theatre culture and develop an - discuss the historical, social and director of theatre, opera and film, appreciation for theatre as an art form. cultural significance of Australian and as a promoter of innovative Raising the Curtain offers students theatre; Australian productions including an opportunity to study: the nature, - observe, experience and write Australian Indigenous drama. diversity and characteristics of theatre about Australian theatre in an » MICHELLE ARROW is a historian, as an art form; how a country’s theatre analytical, critical and reflective writer, teacher and television pre- reflects and shape a sense of na- manner; senter. -

After the Ball David Williamson

David Williamson’s first full-length play, The Coming of Stork, premiered at the La Mama Theatre, Carlton, in 1970 and later became the film Stork, directed by Tim Burstall. The Removalists and Don’s Party followed in 1971, then Jugglers Three (1972), What If You Died Tomorrow? (1973), The Department (1975), A Handful of Friends (1976), The Club (1977) and Travelling North (1979). In 1972 The Removalists won the Australian Writers’ Guild AWGIE Award for best stage play and the best script in any medium and the British production saw Williamson nominated most promising playwright by the London Evening Standard. The 1980s saw his success continue with Celluloid Heroes (1980), The Perfectionist (1982), Sons of Cain (1985), Emerald City (1987) and Top Silk (1989); whilst the 1990s produced Siren (1990), Money and Friends (1991), Brilliant Lies (1993), Sanctuary (1994), Dead White Males (1995), Heretic (1996), Third World Blues (an adaptation of Jugglers Three) and After the Ball (both in 1997), and Corporate Vibes and Face to Face (both in 1999). The Great Man (2000), Up for Grabs, A Conversation, Charitable Intent (all in 2001), Soulmates (2002), Birthrights (2003), Amigos, Flatfoot (both in 2004), Operator and Influence(both 2005) have since followed. Williamson is widely recognised as Australia’s most successful playwright and over the last thirty years his plays have been performed throughout Australia and produced in Britain, United States, Canada and many European countries. A number of his stage works have been adapted for the screen, including The Removalists, Don’s Party, The Club, Travelling North, Emerald City, Sanctuary and Brilliant Lies. -

What Killed Australian Cinema & Why Is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving?

What Killed Australian Cinema & Why is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving? A Thesis Submitted By Jacob Zvi for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Faculty of Health, Arts & Design, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne © Jacob Zvi 2019 Swinburne University of Technology All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. II Abstract In 2004, annual Australian viewership of Australian cinema, regularly averaging below 5%, reached an all-time low of 1.3%. Considering Australia ranks among the top nations in both screens and cinema attendance per capita, and that Australians’ biggest cultural consumption is screen products and multi-media equipment, suggests that Australians love cinema, but refrain from watching their own. Why? During its golden period, 1970-1988, Australian cinema was operating under combined private and government investment, and responsible for critical and commercial successes. However, over the past thirty years, 1988-2018, due to the detrimental role of government film agencies played in binding Australian cinema to government funding, Australian films are perceived as under-developed, low budget, and depressing. Out of hundreds of films produced, and investment of billions of dollars, only a dozen managed to recoup their budget. The thesis demonstrates how ‘Australian national cinema’ discourse helped funding bodies consolidate their power. Australian filmmaking is defined by three ongoing and unresolved frictions: one external and two internal. Friction I debates Australian cinema vs. Australian audience, rejecting Australian cinema’s output, resulting in Frictions II and III, which respectively debate two industry questions: what content is produced? arthouse vs. -

ADAMS, Phillip

DON DUNSTAN FOUNDATION 1 DON DUNSTAN ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Phillip ADAMS This is George Lewkowicz for the Don Dunstan Foundation’s Don Dunstan Oral History Project interviewing Phillip Adams on the 1st May 2008 at Phillip Adams’s residence. The topic of interest is the film industry, Phillip’s advice to Don Dunstan on the setting up of the film industry in South Australia and Don and the arts more generally. Phillip, thanks very much for being willing to do this interview. Can you, just for the record, talk briefly about yourself and how you became interested in the film industry? (clock chimes) Well, by the time I got the phone call from Don I’d spent some years persuading, cajoling, bullying, flattering a rapid succession of prime ministers into doing things. My interest in the film industry was simply as a member of an audience for most of my life and it seemed no-one ever considered it remotely possible that Australia make films. We were an audience for films – leaving aside our extraordinary history of film production, which went back to the dawn of time, which none of us knew about; we didn’t know, for example, we’d made 500 films during the Silent Era alone – so, anyway, nothing was happening. The only film productions in Australia were a couple of very boring industrial docos. But once 1956 arrived with television we had to start doing a few things of our own, and long before I started getting fundamental changes in policy and support mechanisms a law was passed. -

Periodical ^E^Ai FIRST NUMBER of the NORTHWEST

of Periodical ^e^ai VOL. IX, NO. 51 DECEMBER 19, 1914 PRICE 25 CENTS FIRST NUMBER OF THE NORTHWEST QUARTERLY MUSICAL REVIEW THE TOWN CRIER HOLLYWOOD FARM BREEDERS OF Registered Holstein-Friesian Cattle Registered Duroc-Jersey Swine PRODUCERS AND DISTRIBUTORS OF Hollywood Certified Milk Hollywood Pork Sausage Hollywood Fresh Eggs FARM AT HOLLYWOOD, WASHINGTON City Office: 1418 Tenth Ave. :: Phone East 1 5 1 Visitors Always Welcome at the Far m I' A G E < > N E THE TOWN CRIER The Last Few Months Give Proof of Better Times iiv the Growth of Popular Savings It has been said that one of the best indications of the well-being of any com munity is to be found in the growth of the Savings of the people. Measured by this standard, we think that Seattle has every reason to feel satisfied. In the Scandinavian American Bank, which, having the largest Savings De posits in the Northwest, is perhaps the best barometer of popular Savings, the record shows: FIRST—A larger number of Savings Depositors; SECOND—A larger total of Savings Deposits; THIRD—A larger average balance to the credit of each depositor Than ever before in the history of the bank. In addition to these Savings Accounts we should consider:— (A) The Large Dumber of our Savings Depositors who have boughl homes in and around Se attle, (we know they have boughl them because in many cases our Mortgage Department helped to furnish tlie money) : and (B) The still larger number of our Savings Depositors who have invested part of their sav ings in small mortgages and bonds which they bought direct from the bank.