Suggestions and Observations Regarding Utah State Parks And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UMNP Mountains Manual 2017

Mountain Adventures Manual utahmasternaturalist.org June 2017 UMN/Manual/2017-03pr Welcome to Utah Master Naturalist! Utah Master Naturalist was developed to help you initiate or continue your own personal journey to increase your understanding of, and appreciation for, Utah’s amazing natural world. We will explore and learn aBout the major ecosystems of Utah, the plant and animal communities that depend upon those systems, and our role in shaping our past, in determining our future, and as stewards of the land. Utah Master Naturalist is a certification program developed By Utah State University Extension with the partnership of more than 25 other organizations in Utah. The mission of Utah Master Naturalist is to develop well-informed volunteers and professionals who provide education, outreach, and service promoting stewardship of natural resources within their communities. Our goal, then, is to assist you in assisting others to develop a greater appreciation and respect for Utah’s Beautiful natural world. “When we see the land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.” - Aldo Leopold Participating in a Utah Master Naturalist course provides each of us opportunities to learn not only from the instructors and guest speaKers, But also from each other. We each arrive at a Utah Master Naturalist course with our own rich collection of knowledge and experiences, and we have a unique opportunity to share that Knowledge with each other. This helps us learn and grow not just as individuals, but together as a group with the understanding that there is always more to learn, and more to share. -

Explore Logan, Utah

p e r i e n E x c e a h i g h e r e l e vat i o n Mike Bullock Explore Logan, Utah Less than a day’s drive from Yellowstone, Jackson and Utah’s 5 National Parks Visitors Guide 199 North Main, Logan, UT 435-755-1890 Cache Valley is Utah’s hidden treasure. It’s a land of dairy Welcome!farms, small towns, stunning mountains, modest cities, friendly people, higher education and internationally renowned live arts performances. Come discover your own adventure. There’s so much to do. Our majestic mountains provide outstanding all-season outdoor recreation. Utah State University generates intellectual stimulus and the fervor of major college athletics. The American West Heritage Center lets you step back in time with costumed interpreters in 160 acres of living history. The stage of the Utah Festival Opera and Musical Theatre glows with world- class performances. There are numerous dining, lodging and shopping offerings. The qualities of the Valley are at the same time unique and familiar, natural and exceptional. Come, let us show you what we mean— what we treasure. Pronounced “cash” Cache Valley was named by fur trappers who stored their beaver pelts in the area. The word cache is French and means to hide or store one’s treasures. Table of Contents Arts, Museums, and Family Fun p. 4 Dining p. 10 Events and Festivals p. 17 Heritage p. 20 Lodging p. 26 Outdoor Recreation p. 32 Extend Your Adventure p. 43 Adventure Checklist p. 46 Guide to Campgrounds p. -

Vendor List by City

Revised 2/20/14 Vendor List by City Antimony Otter Creek State Park 400 East SR 22 435-624-3268 Beaver Beaver Sport & Pawn 91 N Main 435-438-2100 Blanding Edge of the Cedars/Goosenecks State Parks 660 West 400 North 435-678-2238 Bluffdale Maverik 14416 S Camp Williams Rd 801-446-1180 Boulder Anasazi State Park 46 North Hwy 12 435-335-7308 Brian Head Brian Head Sports Inc 269 South Village Way 435-677-2014 Thunder Mountain Motorsports 539 North Highway 143 435-677-2288 1 Revised 2/20/14 Cannonville Kodachrome State Park 105 South Paria Lane 435-679-8562 Cedar City D&P Performance 110 East Center 435-586-5172 Frontier Homestead State Park 635 North Main 435-586-9290 Maverik 809 W 200 N 435-586-4737 Maverik 204 S Main 435-586-4717 Maverik 444 W Hwy 91 435-867-1187 Maverik 220 N Airport Road 435-867-8715 Ron’s Sporting Goods 138 S Main 435-586-9901 Triple S 151 S Main 435-865-0100 Clifton CO Maverik 3249 F Road 970-434-3887 2 Revised 2/20/14 Cortez CO Mesa Verde Motorsports 2120 S Broadway 970-565-9322 Delta Maverik 44 N US Hwy 6 Dolores Colorado Lone Mesa State Park 1321 Railroad Ave 970-882-2213 Duchesne Starvation State Park Old Hwy 40 435-738-2326 Duck Creek Loose Wheels Service Inc. 55 Movie Ranch Road 435-682-2526 Eden AMP Recreation 2429 N Hwy 158 801-614-0500 Maverik 5100 E 2500 N 801-745-3800 Ephraim Maverik 89 N Main 435-283-6057 3 Revised 2/20/14 Escalante Escalante State Park 710 North Reservoir Road 435-826-4466 Evanston Maverik 350 Front Street 307-789-1342 Maverik 535 County Rd 307-789-7182 Morgan Valley Polaris 1624 Harrison -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

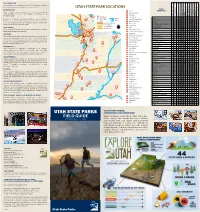

Utah State Parks Are Open Every Day Except for Thanksgiving and Christmas

PLAN YOUR TRIP Utah State Parks are open every day except for Thanksgiving and Christmas. For individual park hours visit our website stateparks.utah.gov. Full UTAH STATE PARK LOCATIONS / PARK RESERVATIONS 1 Anasazi AMENITIES Secure a campsite, pavilion, group area, or boat slip in advance by 2 Antelope Island calling 800-322-3770 8 a.m.–5 p.m. Monday through Friday, or visit 3 Bear Lake stateparks.utah.gov. # Center Visitor / Req. Fee Camping / Group Camping RV Sites Water Hookups—Partial Picnicking / Showers Restrooms Teepees / Yurts / Cabins / Fishing Boating / Biking Hiking Vehicles Off-Highway Golf / Zipline / Archery 84 Cache 3 State Parks 4 Camp Floyd Logan 1. Anasazi F-V R Reservations are always recommended. Individual campsite reservations 23 State Capitol Rivers 5 Coral Pink Sand Dunes Golden Spike Randolph N.H.S. Lakes 2. Antelope Island F-V C-G R-S B H-B may be made up to four months in advance and no fewer than two days Cities Box Elder Wasatch-Cashe N.F. 6 Dead Horse Point G Brigham City Rich 3. Bear Lake F-V C-G P-F R-S C B-F H-B before desired arrival date. Up to three individual campsite reservations per r e Interstate Highway 7 Deer Creek a 4. Camp Floyd Stagecoach Inn Museum F R t customer are permitted at most state parks. 43 U.S. Highway North S 8 East Canyon a 5. Coral Pink Sand Dunes F-V C-G P R-S H l Weber Morgan State Highway t PARK PASSES Ogden 9 Echo L 6. -

Bear River Heritage Area Book

Bear River heritage area Idaho Utah — Julie Hollist Golden Cache Bear Lake Pioneer Spike Valley Country Trails Blessed by Water Worked by Hand The Bear River Heritage Area — Blessed by Water, Worked by Hand fur trade, sixteen rendezvous were held—four in The Bear River those established by more recent immigrants, like Welcome to the Bear what is now the Bear River Heritage Area, and the The head of the Bear River in the Uinta people from Japan, Mexico, Vietnam and more. other twelve within 65 to 200 miles. Cache Valley, Mountains is only about 90 miles from where it Look for cultural markers on the landscape, River Heritage Area! which straddles the Utah-Idaho border (and is ends at the Great Salt Lake to the west. However, like town welcome signs, historic barns and It sits in a dry part of North America, home to Logan, Utah, and Preston, Idaho, among the river makes a large, 500-mile loop through hay stacking machines, clusters of evergreen yet this watershed of the Bear River is others), was named for the mountain man practice three states, providing water, habitat for birds, fish, trees around old cemeteries and town squares of storing (caching) their pelts there. and other animals, irrigation for agriculture and that often contain a church building (like the greener than its surroundings, offering hydroelectric power for homes and businesses. tabernacles in Paris, Idaho; and Brigham City, a hospitable home to wildlife and people Nineteenth Century Immigration Logan, and Wellsville, Utah, and the old Oneida alike. Early Shoshone and Ute Indians, The Oregon Trail brought thousands Reading the Landscape Stake Academy in Preston, Idaho). -

Utah Lake Watch Report 2005

Utah Lake Watch Report 2005 Prepared for Utah Division of Water Quality By Andy Dean, Utah State University Water Quality Extension www.extension.usu.edu/waterquality (435)797-2580 December 12, 2005 For additional copies of this report contact: Nancy Mesner (435)797-2465 [email protected] Introduction The Utah Lake Watch (ULW) program recruits volunteers to take Secchi depth measurements in lakes and reservoirs throughout Utah. This ULW annual report summarizes the results of Secchi depth measurements taken by volunteers throughout the summer of 2005. The data collected through the ULW are submitted to the Utah Division of Water Quality to supplement the data they take through their lakes program. The data can be used by scientists, lake managers, and numerous other organizations to analyze the clarity of and overall health of the lakes. Volunteers are trained individually to use a Secchi disk. The Secchi disk is lowered into the water body and the depth at which it disappears is the Secchi depth. Volunteers are also given information about site location (the DEQ station description or GPS coordinates). The monitoring site is typically the deepest part of the lake or nearest the dam on a reservoir. Standardized data sheets are given to each volunteer, which are returned to the USU Water Quality Extension office (Appendix 1) at the end of the summer season so these data can be recorded and summarized. Results During 2005, Secchi depths were recorded by 16 volunteers on 20 different lakes and reservoirs throughout Utah (23 sites total due to multiple sites in several reservoirs). -

The State of Utah's Travel and Tourism Industry 2017

The State of Utah’s Travel and Tourism Industry 2017 By Jennifer Leaver, Research Analyst April 2017 The State of Utah’s Travel and Tourism Industry Table of Contents Figure 1 Census Population Shares by Utah Travel Region, 2015 Introduction ............................................... 1 Utah Travel Regions ........................................ 2 Utah Travel and Tourism in a National Context .............. 2 Utah Visitor Spending and Profile ........................... 2 Travel -Generated Employment ............................. 5 The Seasonal Nature of Travel and Tourism in Utah .......... 6 Skiing and Snowboarding in Utah .......................... 7 Park Visitation in Utah ...................................... 8 Meetings, Conventions and Trade Shows ................... 9 Travel-Related Sales and Sales Tax Revenue ................. 9 Travel and Tourism Industry Performance .................. 11 Transportation Industry Performance ...................... 12 Arts, Entertainment and Recreation Industry Performance ... 13 Foodservice Industry Performance ........................ 13 Summary ................................................. 13 Appendix A ............................................... 15 Appendix B ............................................... 16 Introduction Utah’s diverse travel and tourism industry generates jobs and income for Utah residents and produces tax revenue for the Source: Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute analysis of Utah Population Estimates state. Domestic and international travelers and tourists are -

A History of Morgan County, Utah Centennial County History Series

610 square miles, more than 90 percent of which is privately owned. Situated within the Wasatch Mountains, its boundaries defined by mountain ridges, Morgan Countyhas been celebrated for its alpine setting. Weber Can- yon and the Weber River traverse the fertile Morgan Valley; and it was the lush vegetation of the pristine valley that prompted the first white settlers in 1855 to carve a road to it through Devils Gate in lower Weber Canyon. Morgan has a rich historical legacy. It has served as a corridor in the West, used by both Native Americans and early trappers. Indian tribes often camped in the valley, even long after it was settled by Mormon pioneers. The southern part of the county was part of the famed Hastings Cutoff, made notorious by the Donner party but also used by Mormon pioneers, Johnston's Army, California gold seekers, and other early travelers. Morgan is still part of main routes of traffic, including the railroad and utility lines that provide service throughout the West. Long known as an agricultural county, the area now also serves residents who commute to employment in Wasatch Front cities. Two state parks-Lost Creek Reservoir and East A HISTORY OF Morgan COUY~Y Linda M. Smith 1999 Utah State Historical Society Morgan County Commission Copyright O 1999 by Morgan County Commission All rights reserved ISBN 0-913738-36-0 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 98-61320 Map by Automated Geographic Reference Center-State of Utah Printed in the United States of America Utah State Historical Society 300 Rio Grande Salt Lake City, Utah 84 101 - 1182 Dedicated to Joseph H. -

OWNER / AGENT Tifie

Tifie Ranch OWNER / AGENT Tifie... a home, Ranch a recreational property, a hunting and fishing ranch, and a corporate retreat! $9,450,000 Morgan Valley Morgan County, Utah LOCATION: North Central Utah in Morgan Valley of Morgan County, a 50- minute drive from downtown Salt Lake City along Interstate 80, State Highway 65, and State Highway 66. ACREAGE: Approximately 164 acres ELEVATION: 5,400 feet at the lodge ZONING: 160 acres per dwelling WATER: One excellent well SEWER: Septic tanks/drain fields ELECTRICAL: On site PROPANE GAS: Truck delivered TELEPHONE: On site INTERNET: Satellite on site 2 intermountain realty group TIFIE RANCH Welcome to Tifie Ranch Hunting, Fishing, Special Event, and Corporate Retreat Offered for the first time, a spectacular, developed property with a 7 bedroom, 7 bathroom lodge, 3 guest cabins, 2 bowerys, 1 barn/tool shed, and a greenhouse. July, 2019 To our family, friends, and business associates, Imagine waking up to crisp mountain air, clear blue skies, and views of the beautiful Morgan Valley less than 1 mile from Welcome to our beloved Tifie Ranch. We built our lodge, moved from the Wasatch front, and began to raise our family on this incredible property 12 years the East Canyon Reservoir boat launching ramp! Enjoy being ago. We have grown to love the serenity and the surprises that the East Canyon surrounded by East Canyon Reservoir, Sheep Canyon, East Basin delivers daily. Our businesses are located in several Utah locations but this Canyon Creek, and owning ground along Highway 66, the is where we return each night to experience the majesties of nature with our children. -

Utah Scenic Byways Guide

Utah is the place where prehistory intersects with the enduring spirit of the Old West. Wild, adventure-rich places cradle vibrant urban centers. With interstates and airplanes, the world can feel pretty small. On Utah’s designated scenic byways, the world feels grand; its horizons seem infinite. As you drive through Utah, you’ll inevitably encounter many of the state’s scenic byways. In total, Utah’s distinct topography provides the surface for 27 scenic byways, which add up to hundreds of miles of vivid travel experiences wherein the road trip is as memorable as the destination. Utah’s All-American Road: Scenic Byway 12 headlines the network of top roads thanks to landscapes and heritage unlike anywhere else in the nation. All of Utah’s scenic byways are explorative journeys filled with trailheads, scenic overlooks, museums, local flavors and vibrant communities where you can stop for the night or hook up your RV. Not sure where to start? In the following pages, you’ll discover monumental upheavals of exposed rock strata among multiple national and state parks along the All-American Road (pg. 4); dense concentrations of fossils along Dinosaur Diamond (pg. 8); and the blazing red cliffs and deep blue waters of Flaming Gorge–Uintas (pg. 12) — and that’s just in the first three highlighted byways. Your journey continues down two dozen additional byways, arranged north to south. Best of all, these byways access an outdoor adventureland you can hike, fish, bike, raft, climb and explore from sunup to sundown — then stay up to welcome the return of the Milky Way. -

2. Characterization of Watershed

East Canyon Reservoir and East Canyon Creek TMDLs May 2010 2. CHARACTERIZATION OF WATERSHED East Canyon Reservoir watershed is located in north-central Utah approximately 20 miles east of Salt Lake City, Utah and 15 miles north of Park City, Utah (Figure 2.1). The watershed drains 145 square miles that includes Park City, Utah and several major ski resorts at its headwaters and a portion of Snyderville Basin from the Morgan–Summit county line to the headwaters of East Canyon Creek (SBWRD 2005). The watershed covers an elevation range from 5,600 feet (1,707 m) at the reservoir to over 10,000 feet (3,049 m) near Park City. Its principal drainage, East Canyon Creek begins just north of I-80 at the confluence of Kimball Creek from the south and an unnamed creek from the north. From there if flows northeast and north to the reservoir (Judd 1999; SBWRD 2005). The State of Utah has designated the beneficial uses of the reservoir and creek as domestic drinking water with prior treatment (1C), primary contact recreation (swimming) (2A), secondary contact recreation (2B), cold water game fish and the associated food chain (3A), and agricultural water supply (4). The cold water game fish designated use (3A) was identified as partially supported on the State of Utah 1998 303(d) list (UDEQ 2000a). The 1992–1997 average total phosphorus concentration in the reservoir water column exceeded the state pollution indicator (0.025 mg/L) at 0.117 mg/L (Judd 1999). This led to the development of a TMDL for East Canyon Reservoir in 2000.