Needs Assessment Report on Wheelchair Service Provision in the Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

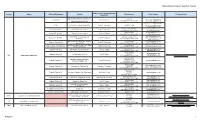

FOI Manuals/Receiving Officers Database

National Government Agencies (NGAs) Name of FOI Receiving Officer and Acronym Agency Office/Unit/Department Address Telephone nos. Email Address FOI Manuals Link Designation G/F DA Bldg. Agriculture and Fisheries 9204080 [email protected] Central Office Information Division (AFID), Elliptical Cheryl C. Suarez (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 2158 [email protected] Road, Diliman, Quezon City [email protected] CAR BPI Complex, Guisad, Baguio City Robert L. Domoguen (074) 422-5795 [email protected] [email protected] (072) 242-1045 888-0341 [email protected] Regional Field Unit I San Fernando City, La Union Gloria C. Parong (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4111 [email protected] (078) 304-0562 [email protected] Regional Field Unit II Tuguegarao City, Cagayan Hector U. Tabbun (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4209 [email protected] [email protected] Berzon Bldg., San Fernando City, (045) 961-1209 961-3472 Regional Field Unit III Felicito B. Espiritu Jr. [email protected] Pampanga (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4309 [email protected] BPI Compound, Visayas Ave., Diliman, (632) 928-6485 [email protected] Regional Field Unit IVA Patria T. Bulanhagui Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4429 [email protected] Agricultural Training Institute (ATI) Bldg., (632) 920-2044 Regional Field Unit MIMAROPA Clariza M. San Felipe [email protected] Diliman, Quezon City (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4408 (054) 475-5113 [email protected] Regional Field Unit V San Agustin, Pili, Camarines Sur Emily B. Bordado (632) 9288756 to 65 loc. 4505 [email protected] (033) 337-9092 [email protected] Regional Field Unit VI Port San Pedro, Iloilo City Juvy S. -

Philippine Report

SECOND QUARTER 2018 PHILIPPINE REPORT CONSTRUCTION MARKET QUARTERLY UPDATE TABLE OF CONTENTS MARKET SUMMARY 1 The Philippine Economy 1 Foreign Direct Investments 2 Philippine Construction 3 CONSTRUCTION MARKET ACTIVITY 4 Construction Market 5 Activity Cycle COMMODITY PRICE TRENDS 6 Metal Prices 6 Steel Reinforcements 6 Crude Oil Prices 6 MATERIAL PRICE TRENDS 7 Retail Price Index 7 Currency Exchange Rates 7 CONSTRUCTION PRICES 8 PROFESSIONAL SERVICES 9 The Lerato Tower 3 Makati City MARKET SUMMARY THE PHILIPPINE ECONOMY Philippine Economy Grows by 6.8% in Q1 2018 The Philippine economy grew by 6.8 percent in the first quarter of 2018. This was faster than the growth recorded in the same quarter of 2017. PHILIPPINES IN FIGURES Manufacturing, Other Services, and Trade were the Population 105.8M main drivers of growth for the quarter. Among the (as of First Quarter 2018) major economic sectors, Industry recorded the fastest growth at 7.9 percent. This was followed by Services with a growth of 7.0 percent. Agriculture Gross National Income 6.40% also grew at a slower pace of 1.5 percent. (as of First Quarter 2018) Net Primary Income increased to 4.3 percent Gross Domestic Product 6.80% during the quarter. Meanwhile, Gross National (as of First Quarter 2018) Income (GNI) posted a growth of 6.4 percent, faster than previous year’s growth of 6.3 percent. Inflation Rate 4.50% With the country’s projected population reaching (as of April 2018) 105.8 million in the first quarter of 2018, per capita GDP grew by 5.1 percent. -

CAREPARTNERS-GUIDEBOOK Web

Being A Carepartner TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . 2 Make Meaning to Stay Positive . 3 Caregiver Stress and Burnout . 4 The 7 Deadly Emotions of Caregiving . 9 Keeping Families Strong . 12 CurePSP Support Groups . 15 Caring From a Distance . 17 Travel Tips . 20 Compassionate Allowances for PSP, CBD, and MSA . 23 Support and Resources . 25 When to Hang Up the Keys . 29 When Is It Time to Get a Wheelchair? . 31 When Should Hospice Be Contacted? . 35 Estate Planning . 37 1 CurePSP Brain Tissue Donation Program . 40 Notes . 45 INTRODUCTION Message from the Chair of CurePSP’s Patient and Carepartner Advocacy Committee Ileen McFarland Those of us who have walked the walk as a patient or carepartner, associated with one of the rare prime of life brain diseases, know all too well the challenges we are confronted with on a day-to-day basis. Patients are stunned at their diagnosis and do not know where to turn and carepartners feel powerless and unqualified in their efforts to comfort and provide care for their loved ones. We here at CurePSP are sensitive to these circumstances and over the years have developed programs and support networks to assist you. The materials we have available to you from the onset of the disease through its course can be obtained by simply calling our office. We have more than 50 support groups nationwide where patients and carepartners meet once a month to discuss their issues and ease their burden. These support groups are led by well-trained facilitators, some of whom have had a personal experience with one of the diseases. -

Assessment of Impediments to Urban-Rural Connectivity in Cdi Cities

ASSESSMENT OF IMPEDIMENTS TO URBAN-RURAL CONNECTIVITY IN CDI CITIES Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project CONTRACT NO. AID-492-H-15-00001 JANUARY 27, 2017 This report is made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the sole responsibility of the International City/County Management Association (ICMA) and do not necessarily reflect the view of USAID or the United States Agency for International Development USAID Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project Page i Pre-Feasibility Study for the Upgrading of the Tagbilaran City Slaughterhouse ASSESSMENT OF IMPEDIMENTS TO URBAN-RURAL CONNECTIVITY IN CDI CITIES Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project CONTRACT NO. AID-492-H-15-00001 Program Title: USAID/SURGE Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Philippines Contract Number: AID-492-H-15-00001 Contractor: International City/County Management Association (ICMA) Date of Publication: January 27, 2017 USAID Strengthening Urban Resilience for Growth with Equity (SURGE) Project Page ii Assessment of Impediments to Urban-Rural Connectivity in CDI Cities Contents I. Executive Summary 1 II. Introduction 7 II. Methodology 9 A. Research Methods 9 B. Diagnostic Tool to Assess Urban-Rural Connectivity 9 III. City Assessments and Recommendations 14 A. Batangas City 14 B. Puerto Princesa City 26 C. Iloilo City 40 D. Tagbilaran City 50 E. Cagayan de Oro City 66 F. Zamboanga City 79 Tables Table 1. Schedule of Assessments Conducted in CDI Cities 9 Table 2. Cargo Throughput at the Batangas Seaport, in metric tons (2015 data) 15 Table 3. -

1623400766-2020-Sec17a.Pdf

COVER SHEET 2 0 5 7 3 SEC Registration Number M E T R O P O L I T A N B A N K & T R U S T C O M P A N Y (Company’s Full Name) M e t r o b a n k P l a z a , S e n . G i l P u y a t A v e n u e , U r d a n e t a V i l l a g e , M a k a t i C i t y , M e t r o M a n i l a (Business Address: No. Street City/Town/Province) RENATO K. DE BORJA, JR. 8898-8805 (Contact Person) (Company Telephone Number) 1 2 3 1 1 7 - A 0 4 2 8 Month Day (Form Type) Month Day (Fiscal Year) (Annual Meeting) NONE (Secondary License Type, If Applicable) Corporation Finance Department Dept. Requiring this Doc. Amended Articles Number/Section Total Amount of Borrowings 2,999 as of 12-31-2020 Total No. of Stockholders Domestic Foreign To be accomplished by SEC Personnel concerned File Number LCU Document ID Cashier S T A M P S Remarks: Please use BLACK ink for scanning purposes. 2 SEC Number 20573 File Number______ METROPOLITAN BANK & TRUST COMPANY (Company’s Full Name) Metrobank Plaza, Sen. Gil Puyat Avenue, Urdaneta Village, Makati City, Metro Manila (Company’s Address) 8898-8805 (Telephone Number) December 31 (Fiscal year ending) FORM 17-A (ANNUAL REPORT) (Form Type) (Amendment Designation, if applicable) December 31, 2020 (Period Ended Date) None (Secondary License Type and File Number) 3 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION SEC FORM 17-A ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 17 OF THE SECURITIES REGULATION CODE AND SECTION 141 OF CORPORATION CODE OF THE PHILIPPINES 1. -

Guidelines: How to Write About People with Disabilities

Guidelines: How to Write about People with Disabilities 9th Edition (On the Cover) Deb Young with her granddaughters. Deb is a triple amputee who uses a power (motorized) wheelchair. Online You can view this information online at our website. You can also download a quick tips poster version or download the full pdf of the Guidelines at http://rtcil.org/sites/rtcil.drupal.ku.edu/files/ files/9thguidelines.jpg Guidelines: How to Write about People with Disabilities You can contribute to a positive image of people with disabilities by following these guidelines. Your rejection of stereotypical, outdated language and use of respectful terms will help to promote a more objective and honest image. Say this Instead of How should I describe you or your disability? What are you? What happened to you? Disability Differently abled, challenged People with disabilities, disabled Handicapped Survivor Victim, suffers from Uses a wheelchair, wheelchair user Confined to a wheelchair Service dog or service animal Seeing eye dog Accessible parking or restroom Handicapped parking, disabled stall Person with Down syndrome Mongoloid Intellectual disability Mentally retarded, mental retardation Autistic, on the autism spectrum, atypical Abnormal Deb Young with her granddaughters. Deb is a triple amputee who uses a power Person with a brain injury Brain damaged motorized) wheelchair. Person of short stature, little person Midget, dwarf For More Information Person with a learning disability Slow learner, retard Download our brochure, Guidelines: How Person with -

Assisted Living Policy and Procedure

Assisted Living Policy and Procedure Subject/Title: Motorized Mobility Aids: Wheelchairs, Carts, and Scooters Pendulum, 4600B Montgomery Blvd. NE, Suite 204, Albuquerque, NM 87109 Reference: (888) 815-8250 • www.WeArePendulum.com I. POLICY GUIDELINES The facility promotes that residents with disabilities and physical limitations have access to devices that improve their independence. Motorized mobility aids may improve access to the facility and services. In order to provide a safe environment for residents, employees, and visitors, the facility maintains a policy for use of motorized mobility aids, whether they are wheelchairs, carts, or scooters. Orientation for safe use of motorized mobility aids augments safety for the resident using these devices as well as other residents, visitors, and employees. Routine inspection of motorized mobility aids promotes the maintenance of equipment that remains in good working order. II. DEFINITION A motorized mobility aid or device is a wheelchair, cart, or scooter that serves as an assistive device to allow an individual to be more independent and/or enables an individual to accomplish a task. In accordance with the Americans with Disabilities Act, Title II, Part 35, Nondiscrimination on the Basis of Disability in State and Local Government Services, Use of other power-driven mobility devices: A public entity shall make reasonable modifications in its policies, practices, or procedures to permit the use of other power-driven mobility devices by individuals with mobility disabilities, unless the public entity can demonstrate that the class of other power-driven mobility devices cannot be operated in accordance with legitimate safety requirements that the public entity has adopted pursuant to § 35.130(h). -

Accessibility Guide Provides Informa- Tion on the Recommendations and Restrictions for Each Attraction

WELCOME Dollywood® proudly offers a wholesome, family-fun experience for our Guests, and we are here to help Create Memories Worth Repeat- ing® for you and your family. We are committed to providing a safe and enjoyable environment for our Guests. This Rider Safety & Accessibility Guide provides informa- tion on the recommendations and restrictions for each attraction. Please carefully read through this guide to learn more about the services we provide, as well as particular attraction information. Additionally, we have included specific information for Guests with disabilities. This information provides a clear outline of the accom- modations at each attraction, as well as the physical requirements for entering or exiting ride vehicles and other attraction areas. It is important to note that, although all of our Hosts are eager to make your day as pleasant as possible, they are not trained in lifting or car- rying techniques and therefore cannot provide physical assistance. We suggest that Guests with disabilities bring a companion who can provide any physical assistance that may be needed. RIDE ACCESSIBILITY CENTER Our Ride Accessibility Center is provided to assist Guests with dis- abilities and provide detailed information about special services and rider requirements to help you make well-informed decisions about your visit. Guests who wish to use the Ride Accessibility Entrances must visit the Ride Accessibility Center (located next to the Dollywood Em- porium) to obtain a Ride Accessibility Pass. See page 9 for details about this program. Please Note: The information in this guide is subject to change. Please feel free to visit our Ride Accessibility Center for current information on accessibility services. -

ANALYSIS of the CHARCOAL VALUE CHAIN in ILOILO CITY (Final Report)

ANALYSIS OF THE CHARCOAL VALUE CHAIN IN ILOILO CITY (Final Report) BUILDING LOW EMISSION ALTERNATIVES TO DEVELOP ECONOMIC RESILIENCE AND SUSTAINABILITY PROJECT (B-LEADERS) September 2017 This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). It was prepared by the Building Low Emission Alternatives to Develop Economic Resilience and Sustainability (B- LEADERS) Project implemented by RTI International for USAID Philippines. ANALYSIS OF THE CHARCOAL VALUE CHAIN IN ILOILO CITY (Final Report) BUILDING LOW EMISSION ALTERNATIVES TO DEVELOP ECONOMIC RESILIENCE AND SUSTAINABILITY PROJECT (B-LEADERS) September 2017 DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ··································································· I LIST OF TABLES ········································································ III LIST OF FIGURES ······································································ III ACRONYMS ················································································ IV EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ································································· 1 I. INTRODUCTION ································································ 4 1.1. Objectives ............................................................................................................ 6 1.2. Scope and Limitations ....................................................................................... -

Two Centuries of Wheelchair Design, from Furniture to Film

Enwheeled: Two Centuries of Wheelchair Design, from Furniture to Film Penny Lynne Wolfson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the History of the Decorative Arts and Design MA Program in the History of the Decorative Arts and Design Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution and Parsons The New School for Design 2014 2 Fall 08 © 2014 Penny Lynne Wolfson All Rights Reserved 3 ENWHEELED: TWO CENTURIES OF WHEELCHAIR DESIGN, FROM FURNITURE TO FILM TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS i PREFACE ii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1. Wheelchair and User in the Nineteenth Century 31 CHAPTER 2. Twentieth-Century Wheelchair History 48 CHAPTER 3. The Wheelchair in Early Film 69 CHAPTER 4. The Wheelchair in Mid-Century Films 84 CHAPTER 5. The Later Movies: Wheelchair as Self 102 CONCLUSION 130 BIBLIOGRAPHY 135 FILMOGRAPHY 142 APPENDIX 144 ILLUSTRATIONS 150 4 List of Illustrations 1. Rocking armchair adapted to a wheelchair. 1810-1830. Watervliet, NY 2. Pages from the New Haven Folding Chair Co. catalog, 1879 3. “Dimension/Weight Table, “Premier” Everest and Jennings catalog, April 1972 4. Screen shot, Lucky Star (1929), Janet Gaynor and Charles Farrell 5. Man in a Wheelchair, Leon Kossoff, 1959-62. Oil paint on wood 6. Wheelchairs in history: Sarcophagus, 6th century A.D., China; King Philip of Spain’s gout chair, 1595; Stephen Farffler’s hand-operated wheelchair, ca. 1655; and a Bath chair, England, 18th or 19th century 7. Wheeled invalid chair, 1825-40 8. Patent drawing for invalid locomotive chair, T.S. Minniss, 1853 9. -

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper Mckinley Rd. Mckinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date < November 11, 2019 > 1 ALLOWED MARKS PUBLISHED FOR OPPOSITION .................................................................................................... 2 1.1 ALLOWED NATIONAL MARKS .............................................................................................................................................. 2 Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date < November 11, 2019 > 1 ALLOWED MARKS PUBLISHED FOR OPPOSITION 1.1 Allowed national marks Application No. Filing Date Mark Applicant Nice class(es) Number 7 January PHILIPPINE GRAND Formula One Licensing BV 1 4/1419/00000314 9 2019 PRIX [NL] FORMULA 1 7 January Formula One Licensing BV 2 4/1919/00000315 PHILIPPINES GRAND 41 2019 [NL] PRIX HOCO TECHNOLOGY 5 April 3 4/2016/00003537 HOCO. DEVELOPMENT 9 2016 (SHENZHEN) CO., LTD. [CN] 31 July RMCEA Metal Manufacturing 4 4/2017/00012099 FIGHTING TEXAS 21 2017 Corporation [PH] 6 October VIERA DMCI Project Developers, Inc. 5 4/2017/00016145 35; 36 and37 2017 RESIDENCES [PH] 26 October A. Menarini Asia-Pacific 6 4/2017/00017418 MIDOL 5 2017 Holdings Pte Ltd [SG] 22 7 4/2017/00018826 November SHISHI SAFETY Jason Perez Chua [PH] 9 and18 2017 8 January LKK Health Products Group 3; 9; 29; 30; 32 8 4/2018/00000363 INFINITUS 2018 Limited [HK] and35 26 January 20; 21; 24; 27 9 4/2018/00001622 KONA SOL Target Brands, Inc. [US] 2018 and28 18 April Maximum Savings Bank, Inc. -

2015 Edition TESDA: the Authority in Technical Education and Skills Development Republic Act No

2015 Edition TESDA: The Authority in Technical Education and Skills Development Republic Act No. 7796, otherwise known as the Technical Education and Skills Development Act of 1994, declares the policy of the State to provide relevant, accessible, high quality and efficient technical education and skills development (TESD) in support of the development of high quality Filipino middle-level manpower responsive to and in accordance with Philippine development goals and priorities. The Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA) is tasked to manage and supervise TESD in the Philippines. Vision TESDA is the leading partner in the development of the Filipino work- force with world-class competence and positive work values. Mission TESDA provides direction, policies, programs and standards towards quality technical education and skill development. Values Statement We believe in demonstrated competence, institutional integrity, personal commitment and deep sense of nationalism. Quality Policy "We measure our worth by the satisfaction of the customers we serve" Through: Strategic Decisions Effectiveness Responsiveness Value Adding Integrity Citizen focus Efficiency MESSAGE TESDA recognizes that whatever strides the Philippine technical vocational education and training (TVET) sector has achieved through the years cannot be solely attributed to the Agency. These accomplishments are results of the concerted efforts of all stakeholders who share the vision of developing the Filipino workforce that is armed with competencies that respond to the challenges of the new global economic landscape. The Agency therefore continues to expand and strengthen partnership with various groups and institutions. These partnerships have paved the way to improved public perception on TVET and TESDA and better opportunities to its graduates.