Chiptune: the Ludomusical Shaping of Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chiptuning Intellectual Property: Digital Culture Between Creative Commons and Moral Economy

Chiptuning Intellectual Property: Digital Culture Between Creative Commons and Moral Economy Martin J. Zeilinger York University, Canada [email protected] Abstract This essay considers how chipmusic, a fairly recent form of alternative electronic music, deals with the impact of contemporary intellectual property regimes on creative practices. I survey chipmusicians’ reusing of technology and content invoking the era of 8-bit video games, and highlight points of contention between critical perspectives embodied in this art form and intellectual property policy. Exploring current chipmusic dissemination strategies, I contrast the art form’s links to appropriation-based creative techniques and the ‘demoscene’ amateur hacking culture of the 1980s with the chiptune community’s currently prevailing reliance on Creative Commons licenses for regulating access. Questioning whether consideration of this alternative licensing scheme can adequately describe shared cultural norms and values that motivate chiptune practices, I conclude by offering the concept of a moral economy of appropriation-based creative techniques as a new framework for understanding digital creative practices that resist conventional intellectual property policy both in form and in content. Keywords: Chipmusic, Creative Commons, Moral Economy, Intellectual Property, Demoscene Introduction The chipmusic community, like many other born-digital creative communities, has a rich tradition of embracing and encouraged open access, collaboration, and sharing. It does not like to operate according to the logic of informational capital and the restrictive enclosure movements this logic engenders. The creation of chipmusic, a form of electronic music based on the repurposing of outdated sound chip technology found in video gaming devices and old home computers, centrally involves the reworking of proprietary cultural materials. -

Videogame Music: Chiptunes Byte Back?

Videogame Music: chiptunes byte back? Grethe Mitchell Andrew Clarke University of East London Unaffiliated Researcher and Institute of Education 78 West Kensington Court, University of East London, Docklands Campus Edith Villas, 4-6 University Way, London E16 2RD London W14 9AB [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Musicians and sonic artists who use videogames as their This paper will explore the sonic subcultures of videogame medium or raw material have, however, received art and videogame-related fan art. It will look at the work of comparatively little interest. This mirrors the situation in art videogame musicians – not those producing the music for as a whole where sonic artists are similarly neglected and commercial games – but artists and hobbyists who produce the emphasis is likewise on the visual art/artists.1 music by hacking and reprogramming videogame hardware, or by sampling in-game sound effects and music for use in It was curious to us that most (if not all) of the writing their own compositions. It will discuss the motivations and about videogame art had ignored videogame music - methodologies behind some of this work. It will explore the especially given the overlap between the two communities tools that are used and the communities that have grown up of artists and the parallels between them. For example, two around these tools. It will also examine differences between of the major videogame artists – Tobias Bernstrup and Cory the videogame music community and those which exist Archangel – have both produced music in addition to their around other videogame-related practices such as modding gallery-oriented work, but this area of their activity has or machinima. -

Spsg Sn76489 User Manual

SUPER PSG VST SN76489 SMS www.alyjameslab.com USER MANUAL 1.0 BY Aly James ©2013-2014 ALYJAMESLAB TABLE OF CONTENTS SUPER PSG VST ..................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................. 3 INSTALLATION............................................................................................................................... 6 CONTROL PANELS ......................................................................................................................... 9 THE SN76489 PSG CHIP ................................................................................................................11 MAIN CONTROLS..........................................................................................................................15 SETTINGS .....................................................................................................................................17 AMP GENERATOR.........................................................................................................................19 PITCH GENERATOR .......................................................................................................................22 ARPEGGIATOR .............................................................................................................................25 SPECIAL - TIMERS & AY-EG ............................................................................................................27 -

Use of Progressive Rock in David Wise's Soundtrack for Donkey Kong

Use of Progressive Rock in David Wise’s Soundtrack for Donkey Kong Country and the Advancement of Video Game Music Brooke Spencer Professor Stephanie Lind MUSC501 3 March 2019 Introduction In 1994, Nintendo released the Super Nintendo game: Donkey Kong Country (DKC)– resulting in widespread popularity and new innovative use of music in gameplay. Through the utilization of prog-rock in David Wise’s soundtrack for DKC, Nintendo has expanded its range of musical styles, function, and status as a top contending videogame company. The use of prog-rock can be broken down in David Wise’s three pieces: “Treetop Rock”, “Fear Factory”, and “Aquatic Ambience”. Through elements of prog-rock seen in each of these pieces - harmonic prolongation, fragmentation, distortion, and use of the concept ‘meta- chord’ – we can see that DKC’s music was unlike anything Nintendo had been creating previously, and set expectations for music in videogames to come. History Starting in 1977-78, the video game industry began to rise in popularity through arcades. In the 1960s/1970s when first-generation home consoles were created, sound was not a possibility. It was only when Pong was released on the Atari home console in 1975 that sounds were used deliberately: the game had 3 different sounds coinciding with actions on screen: the ball hitting the wall, the paddle, and a sound for player failure. Most games included sound in future releases to increase profits after Pong’s success.1 By the end of the 70s, arcades were growing in popularity, with Nintendo a primary arcade console producer. -

Hyperbole Followed by Disillusion

EDITORIAL Hyperbole Followed By Disillusion ew technology is invariably preceded by challenge of broadening the use base is a difficult as hyperbole and followed by disillusionment. ever. N The short-term impact of new technology is What was not as widely predicted in 1983, but has generally overestimated, while the long-term impact is become hugely significant, is the impact of electronics almost always underestimated," noted the chairman of on the way music is being made and performed today. AT&T in a recent interview. He was discussing the Guitars are currently in the forefront of popular music, evolution of the much heralded "information but behind the scene arsenals of electronics, ranging superhighway," but his words could have just as from signal processing to tone modules, are employed easily been used to describe the evolution of the to help produce that "true acoustic sound." The electronic music industry. marriage between MIDI, the entire family of In one form or another, electronic musical electronic instruments, and the computer has also instruments have existed for over 50 years, but from a made it possible for people working in their living commercial standpoint the synthesizer and electronic rooms to create recordings that previously would have music market has been an important industry sales required a $500,000 studio. Consumers may not have component only for the past 12 years. The only thing embraced electronic music to the extent predicted, but that has changed as rapidly as technology in that then no one anticipated that electronic music would relatively brief time span has been the outlook of end up on virtually every popular recording, including retailers and manufacturers. -

Vintage Game Consoles: an INSIDE LOOK at APPLE, ATARI

Vintage Game Consoles Bound to Create You are a creator. Whatever your form of expression — photography, filmmaking, animation, games, audio, media communication, web design, or theatre — you simply want to create without limitation. Bound by nothing except your own creativity and determination. Focal Press can help. For over 75 years Focal has published books that support your creative goals. Our founder, Andor Kraszna-Krausz, established Focal in 1938 so you could have access to leading-edge expert knowledge, techniques, and tools that allow you to create without constraint. We strive to create exceptional, engaging, and practical content that helps you master your passion. Focal Press and you. Bound to create. We’d love to hear how we’ve helped you create. Share your experience: www.focalpress.com/boundtocreate Vintage Game Consoles AN INSIDE LOOK AT APPLE, ATARI, COMMODORE, NINTENDO, AND THE GREATEST GAMING PLATFORMS OF ALL TIME Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton First published 2014 by Focal Press 70 Blanchard Road, Suite 402, Burlington, MA 01803 and by Focal Press 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Focal Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2014 Taylor & Francis The right of Bill Loguidice and Matt Barton to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Oberheim Prommer MIDI Sampler/ PROM Programmer USER's GUIDE

Oberheim Prommer MIDI Sampler/ PROM programmer USER'S GUIDE Prommer User's Guide Table of Contents 1 Prommer User's Guide Table of Contents 2 Oberheim Prommer User's Guide By Paul J. White Preliminary Edition, June 1986 CAUTION: To prevent fire or shock hazard, do not expose this appliance to rain or moisture. Do not remove cover. No user servicable parts inside. Refer servicing to qualified service personnel. WARNING: This equipment generates and uses radio frequency energy and if not installed and used properly, i.e., in strict accordance with the instruction manual, may cause harmful interference to radio communications. Operation of this equipment in a residential area is likely to cause interference in which case the user at his own expense will be required to take whatever measures may be required to correct the interference. © 1986 - Oberheim - A division of ECC Development Corporation 11650 W. Olympic Blvd. , Los Angeles, CA 90064 All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part is prohibited without permission. Oberheim, the Oberheim logo, Prommer, Matrix-12, Stretch, DMX, and DX are trademarks of ECC Development Corporation. Drumtraks is a trademark of SEQUENTIAL (Sequential Circuits, Inc.) Simmons is a trademark of Simmons Electronics Limited LinnDrum and Linn9000 are trademarks of Linn Electronics, Inc. Prommer User's Guide Table of Contents 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. Introduction 7 2. Getting started 9 3. Blocks 13 A. Select block B. Block address C. Block length D. Protect 4. Sampling 17 A. Sample rate B. Sample time display C. Record trigger threshold D. How to record a sound 5. -

Game Music Como Produto Cultural Autônomo: Como Ela Ultrapassa Os Limites Do Jogo E Se Insere Em Outras Mídias∗

Game music como produto cultural autônomo: como ela ultrapassa os limites do jogo e se insere em outras mídias∗ Camila Schäfery Índice cada vez mais visível também fora do uni- verso dos videogames. A partir desses estu- Introdução1 dos, da análise dos processos de autonomiza- 1 Game Music: Importância e Funções2 ção, concluiu-se que a game music, além de 2 Processos de Autonomização3 sua importância para os jogos, constitui-se Conclusão 12 num novo fenômeno midiático que a cada Bibliografia 13 dia cresce e contagia mais pessoas ao redor do mundo. Resumo Palavras-chave: game music, música, jo- gos eletrônicos. A música, nos jogos eletrônicos, além de servir como fundo, também é utilizada como forma de potencializar a experiência Introdução de imersão e interatividade do jogador. Con- siderando seu papel no game como de ex- UALQUER estudo na área de trema importância, este artigo procura ana- Q videogames é um desafio. Mesmo lisar como a música de videogames se tornou fazendo parte de nossas vidas há décadas, um produto cultural autônomo. Depois de essa mídia de entretenimento sempre foi realizada a pesquisa bibliográfica, foi ana- vista como brinquedo de criança e apenas lisado o movimento de autonomização da hoje ela ganha contornos mais sérios. A game music para identificar em quais mídias música, por outro lado, que é uma forma de esse tipo de música se insere atualmente e arte, sempre refletiu modismos e caracterís- como ela está se tornando uma manifestação ticas da sociedade de cada época. Agora, com a evolução tecnológica dos séculos XX ∗Artigo originalmente publicado na Revista Fron- e XXI, o impacto dela tem se expandido em teiras, v.13, n. -

Introduction Consoles

SUPER AUDIO CART Rack Extension Version Produced by Impact Soundworks in collaboration with OverClocked ReMix Version 1.0.0 Introduction Foreword from Impact Soundworks: Super Audio Cart faithfully reproduces the sound of seven classic video game systems whose cultural legacy and influence has lasted far beyond their commercial lifespans. When the library was conceived, our goal was superb authenticity by deep-sampling every sound chip. But over time, we expanded our vision to shatter the limitations of the original systems and allow for greatly expanded sound design possibilities. The final version of Super Audio Cart is the culmination of 2+ years of intense research, development, and sound design. With a massive 5,500+ samples meticulously recorded, edited, and looped, we’ve thoroughly captured the raw capabilities of each game system. These sounds are loaded into a custom Rack Extension with slick sound design tools to inspire both chiptune music and modern genres. To create this instrument, everyone involved needed a passion and deep connection to both video games and their music. That’s why we collaborated with OverClocked ReMix, a website and community dedicated to the appreciation of game music. To us, Super Audio Cart represents the ultimate tribute to that art form, and we know that it will find a place in your music for many years to come! Consoles 2600 The first mainstream home video game console released in 1977. Though its graphics and audio are incredibly primitive by today’s standards, it has an enduring dual legacy: it created the first video game market boom, as well as the first video game market crash, in 1982. -

Text-Based Description of Music for Indexing, Retrieval, and Browsing

JOHANNES KEPLER UNIVERSITAT¨ LINZ JKU Technisch-Naturwissenschaftliche Fakult¨at Text-Based Description of Music for Indexing, Retrieval, and Browsing DISSERTATION zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor im Doktoratsstudium der Technischen Wissenschaften Eingereicht von: Dipl.-Ing. Peter Knees Angefertigt am: Institut f¨ur Computational Perception Beurteilung: Univ.Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Gerhard Widmer (Betreuung) Ao.Univ.Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Andreas Rauber Linz, November 2010 ii Eidesstattliche Erkl¨arung Ich erkl¨are an Eides statt, dass ich die vorliegende Dissertation selbstst¨andig und ohne fremde Hilfe verfasst, andere als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel nicht benutzt bzw. die w¨ortlich oder sinngem¨aß entnommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht habe. iii iv Kurzfassung Ziel der vorliegenden Dissertation ist die Entwicklung automatischer Methoden zur Extraktion von Deskriptoren aus dem Web, die mit Musikst¨ucken assoziiert wer- den k¨onnen. Die so gewonnenen Musikdeskriptoren erlauben die Indizierung um- fassender Musiksammlungen mithilfe vielf¨altiger Bezeichnungen und erm¨oglichen es, Musikst¨ucke auffindbar zu machen und Sammlungen zu explorieren. Die vorgestell- ten Techniken bedienen sich g¨angiger Web-Suchmaschinen um Texte zu finden, die in Beziehung zu den St¨ucken stehen. Aus diesen Texten werden Deskriptoren gewon- nen, die zum Einsatz kommen k¨onnen zur Beschriftung, um die Orientierung innerhalb von Musikinterfaces zu ver- • einfachen (speziell in einem ebenfalls vorgestellten dreidimensionalen Musik- interface), als Indizierungsschlagworte, die in Folge als Features in Retrieval-Systemen f¨ur • Musik dienen, die Abfragen bestehend aus beliebigem, beschreibendem Text verarbeiten k¨onnen, oder als Features in adaptiven Retrieval-Systemen, die versuchen, zielgerichtete • Vorschl¨age basierend auf dem Suchverhalten des Benutzers zu machen. -

A Retrospective Analysis and the Future for Game Music. Bbw Hochschule

Interactive Music writing in the Age of AI: A retrospective analysis and the future for game music. bbw Hochschule – Management of Creative Industries MA Ugur, Huseyin Can Matriculation Number: 037201 Course Code: HM029 Primary supervisor – Peter Mathias Konhäusner Secondary supervisor – Prof. Dr. Ingo Schünemann Submitted on: 26/09/2020 Abstract In this thesis, the practices, workers and monetary aspects of interactive music industry has been investigated. As the terminology regarding this industry is observed to be ambiguous, each of the elements that make up the industry and where they came from were explored. Once the definitions and their relevance to industry have been established, the effects of progressive technology on this industry have been hypothesized. As technologies such as Virtual Reality and Augmented reality are still limited to niche area of console gaming and just recently making their appearance on mainstream, they have been only mentioned. However, with the all-encompassing nature of Artificial Intelligence technologies and what they offer to software industry int this thesis it is hypothesized to impact the industry on its population of workers and their financial and professional practices. As the industry has been observed to be in a stable state financially and dependent on the gaming industry itself, it is proposed that the biggest impact will be in their use of technology and how they can bring new dimensions to future games have been discussed. Furthermore, as these effects have been described anecdotally, to observe the psychosomatic experience a more developed game music can offer, an experiment game based on earlier studies in the field have been conducted. -

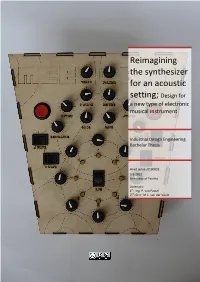

Design for a New Type of Electronic Musical Instrument

Reimagining the synthesizer for an acoustic setting; Design for a new type of electronic musical instrument Industrial Design Engineering Bachelor Thesis Arvid Jense s0180831 5-3-2013 University of Twente Assessors: 1st: Ing. P. van Passel 2nd: Dr.Ir. M.C. van der Voort Reimagining the synthesizer for an acoustic setting; Design for a new type of electronic musical instrument By: Arvid Jense S0180831 Industrial Design Engineering University of Twente Presentation: 5-3-2013 Contact: Create Digital Media/Meeblip Betahaus, to Peter Kirn Prinzessinnenstrasse 19-20 BERLIN, 10969 Germany www.creadigitalmusic.com www.meeblip.com Examination committee: Dr.Ir. M.C. van der Voort Ing. P. van Passel Peter Kirn ii iii ABSTRACT A design of a new type of electronic instrument was made to allow usage in a setting previously not suitable for these types of instrument. Following an open-ended design brief, an analysis of the Meeblip market, synthesizer design literature and three case-studies, a new usage scenario was chosen. The scenario describes a situation of spontaneous music creation at an outside location. A rapidly iterating design process produced a wooden, semi-computational operated synthesizer which has an integrated power supply, amplifier and speaker. Care was taken to allow for rich and musical interaction as well as making the sound quality of the instrument on a similar level as acoustic instruments. Keywords: Synthesizer design, Electronics design, Open source, Arduino, Meeblip, Interaction design SAMENVATTING (DUTCH) Een ontwerp is gemaakt voor een nieuw type elektronisch muziek instrument welke gebruikt kan worden in een setting die eerder niet geschikt was voor elektronische instrumenten.