3 Prisons & a Ferryman's Seat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mitchell Final4print.Pdf

VICTORIAN CRITICAL INTERVENTIONS Donald E. Hall, Series Editor VICTORIAN LESSONS IN EMPATHY AND DIFFERENCE Rebecca N. Mitchell THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Columbus Copyright © 2011 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mitchell, Rebecca N. (Rebecca Nicole), 1976– Victorian lessons in empathy and difference / Rebecca N. Mitchell. p. cm. — (Victorian critical interventions) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-1162-5 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-8142-1162-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8142-9261-7 (cd) 1. English literature—19th century—History and criticism. 2. Art, English—19th century. 3. Other (Philosophy) in literature. 4. Other (Philosophy) in art. 5. Dickens, Charles, 1812–1870— Criticism and interpretation. 6. Eliot, George, 1819–1880—Criticism and interpretation. 7. Hardy, Thomas, 1840–1928—Criticism and interpretation. 8. Whistler, James McNeill, 1834– 1903—Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Series: Victorian critical interventions. PR468.O76M58 2011 820.9’008—dc22 2011010005 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1162-5) CD-ROM (ISBN 978-0-8142-9261-7) Cover design by Janna Thompson Chordas Type set in Adobe Palatino Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materi- als. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS List of Illustrations • vii Preface • ix Acknowledgments • xiii Introduction Alterity and the Limits of Realism • 1 Chapter 1 Mysteries of Dickensian Literacies • 27 Chapter 2 Sawing Hard Stones: Reading Others in George Eliot’s Fiction • 49 Chapter 3 Thomas Hardy’s Narrative Control • 70 Chapter 4 Learning to See: Whister's Visual Averstions • 88 Conclusion Hidden Lives and Unvisited Tombs • 113 Notes • 117 Bibliography • 137 Index • 145 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1 James McNeill Whistler, The Miser (1861). -

DATES of TRIALS Until October 1775, and Again from December 1816

DATES OF TRIALS Until October 1775, and again from December 1816, the printed Proceedings provide both the start and the end dates of each sessions. Until the 1750s, both the Gentleman’s and (especially) the London Magazine scrupulously noted the end dates of sessions, dates of subsequent Recorder’s Reports, and days of execution. From December 1775 to October 1816, I have derived the end dates of each sessions from newspaper accounts of the trials. Trials at the Old Bailey usually began on a Wednesday. And, of course, no trials were held on Sundays. ***** NAMES & ALIASES I have silently corrected obvious misspellings in the Proceedings (as will be apparent to users who hyper-link through to the trial account at the OBPO), particularly where those misspellings are confirmed in supporting documents. I have also regularized spellings where there may be inconsistencies at different appearances points in the OBPO. In instances where I have made a more radical change in the convict’s name, I have provided a documentary reference to justify the more marked discrepancy between the name used here and that which appears in the Proceedings. ***** AGE The printed Proceedings almost invariably provide the age of each Old Bailey convict from December 1790 onwards. From 1791 onwards, the Home Office’s “Criminal Registers” for London and Middlesex (HO 26) do so as well. However, no volumes in this series exist for 1799 and 1800, and those for 1828-33 inclusive (HO 26/35-39) omit the ages of the convicts. I have not comprehensively compared the ages reported in HO 26 with those given in the Proceedings, and it is not impossible that there are discrepancies between the two. -

Victorian Heroes: Peabody, Waterlow, and Hartnoll ______

Victorian Heroes: Peabody, Waterlow, and Hartnoll ____________________________________________________________________________________ Victorian Heroes: Peabody, Waterlow, and Hartnoll The development of housing for the working- classes in Victorian Southwark Part 2: The buildings of Southwark Martin Stilwell © Martin Stilwell 2015 Page 1 of 46 Victorian Heroes: Peabody, Waterlow, and Hartnoll ____________________________________________________________________________________ This paper is Part 2 of a dissertation by the author for a Master of Arts in Local History from Kingston University in 2005. It covers the actual philanthropic housing schemes before WW1. Part 1 covered Southwark, its history and demographics of the time. © Martin Stilwell 2015 Page 2 of 46 Victorian Heroes: Peabody, Waterlow, and Hartnoll ____________________________________________________________________________________ © Martin Stilwell 2015 Page 3 of 46 Victorian Heroes: Peabody, Waterlow, and Hartnoll ____________________________________________________________________________________ Cromwell Buildings, Red Cross Street 1864, Improved Industrial Dwellings Company (IIDC) 18 dwellings, 64 rooms1, 61 actual residents on 1901 census2 At first sight, it is a surprise that this relatively small building has survived in a predominantly commercial area. This survival is mainly due to it being a historically significant building as it is only the second block built by Sydney Waterlow’s IIDC, and the first of a new style developed by Waterlow in conjunction with builder -

Green Linkslinks –– a a Walkingwalking && Cyclingcycling Networknetwork Forfor Southwsouthwarkark

GreenGreen LinksLinks –– A A WalkingWalking && CyclingCycling NetworkNetwork forfor SouthwSouthwarkark www.southwarklivingstreets.org.uk 31st31st MarchMarch 20102010 www.southwarkcyclists.org.uk Contents. Proposed Green Links - Overview Page Introduction 3 What is a Green Link? 4 Objectives of the Project 5 The Nature of the Network 6 The Routes in Detail 7 Funding 18 Appendix – Map of the Green Links Network 19 2 (c) Crown Cop yright. All rights reserved ((0)100019252) 2009 Introduction. • Southwark Living Streets and Southwark Cyclists have developed a proposal for a network of safe walking and cycling routes in Southwark. • This has been discussed in broad outline with Southwark officers and elements of it have been presented to some Community Councils. • This paper sets out the proposal, proposes next steps and invites comments. 3 What is a Green Link? Planting & Greenery Biodiverse Connects Local Safe & Attractive Amenities Cycle Friendly Pedestrian Friendly Surrey Canal Path – Peckham Town Centre to Burgess Park 4 Objectives. • The purpose of the network is to create an alternative to streets that are dominated by vehicles for residents to get about the borough in a healthy, safe and pleasant environment in their day-to-day journeys for work, school shopping and leisure. • The routes are intended to provide direct benefits… - To people’s physical and mental health. - In improving the environment in terms of both air and noise. - By contributing to the Council meeting its climate change obligations, by offering credible and attractive alternatives to short car journeys. - Encouraging people make a far greater number and range of journeys by walking and cycling. • More specifically the network is designed to: - Take advantage of Southwark’s many large and small parks and open spaces, linking them by routes which are safe, and perceived to be safe, for walking and cycling. -

Different Faces of One ‘Idea’ Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek

Different faces of one ‘idea’ Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek To cite this version: Jean-Yves Blaise, Iwona Dudek. Different faces of one ‘idea’. Architectural transformations on the Market Square in Krakow. A systematic visual catalogue, AFM Publishing House / Oficyna Wydawnicza AFM, 2016, 978-83-65208-47-7. halshs-01951624 HAL Id: halshs-01951624 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01951624 Submitted on 20 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Architectural transformations on the Market Square in Krakow A systematic visual catalogue Jean-Yves BLAISE Iwona DUDEK Different faces of one ‘idea’ Section three, presents a selection of analogous examples (European public use and commercial buildings) so as to help the reader weigh to which extent the layout of Krakow’s marketplace, as well as its architectures, can be related to other sites. Market Square in Krakow is paradoxically at the same time a typical example of medieval marketplace and a unique site. But the frontline between what is common and what is unique can be seen as “somewhat fuzzy”. Among these examples readers should observe a number of unexpected similarities, as well as sharp contrasts in terms of form, usage and layout of buildings. -

7 Archaeological Potential and Significance

Joseph Lancaster Nursery Site, London Borough of Southwark, SE1 4EX: An Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment ©Pre-Construct Archaeology Ltd, June 2017 7 ARCHAEOLOGICAL POTENTIAL AND SIGNIFICANCE 7.1 General 7.2 The site is located on the southern edge of the Thames Valley Floodplain of the River Thames Basin. The settlement of Southwark grew up around two gravel eyots – often referred to as the north and south islands – that were separated from the ‘mainland’ to the south by the Borough Channel. It was this series of gravel eyots upon which the bridge crossing to Londinium was constructed and connected to the south by Road 1. South of the Borough Channel and on higher ground the road splintered into Stane Street (running to Chichester) and Watling Street (running to Canterbury and Dover). The study area is located south of this road junction in an area that has become identified as the ‘Southern Cemeteries’ to denote it as separate to those cemeteries around Londinium on the north bank of the Thames. 7.3 Prehistoric 7.3.1 Pottery and worked flints found in north Southwark indicate that the area was frequented in the Mesolithic and later settled from the late Neolithic to early Bronze Age period onwards. What had been an intertidal zone would have varied in character depending on the periodic rising and falling of sea level due to climatic fluctuations (Killock 2010:12). However, the nature of that settlement is still poorly understood and most of the finds recorded on the HER from these periods are residual - suggesting a background presence of dispersed activity across north Southwark with the Mesolithic activity focussed closer to the Thames and the gravel eyots. -

Prisons and Punishments in Late Medieval London

Prisons and Punishments in Late Medieval London Christine Winter Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London Royal Holloway, University of London, 2012 2 Declaration I, Christine Winter, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 3 Abstract In the history of crime and punishment the prisons of medieval London have generally been overlooked. This may have been because none of the prison records have survived for this period, yet there is enough information in civic and royal documents, and through archaeological evidence, to allow a reassessment of London’s prisons in the later middle ages. This thesis begins with an analysis of the purpose of imprisonment, which was not merely custodial and was undoubtedly punitive in the medieval period. Having established that incarceration was employed for a variety of purposes the physicality of prison buildings and the conditions in which prisoners were kept are considered. This research suggests that the periodic complaints that London’s medieval prisons, particularly Newgate, were ‘foul’ with ‘noxious air’ were the result of external, rather than internal, factors. Using both civic and royal sources the management of prisons and the abuses inflicted by some keepers have been analysed. This has revealed that there were very few differences in the way civic and royal prisons were administered; however, there were distinct advantages to being either the keeper or a prisoner of the Fleet prison. Because incarceration was not the only penalty available in the enforcement of law and order, this thesis also considers the offences that constituted a misdemeanour and the various punishments employed by the authorities. -

Byelaws for Parks and Open Spaces

London Borough of Southwark BYELAWS FOR PLEASURE GROUNDS, PUBLIC WALKS AND OPEN SPACES ARRANGEMENT OF BYELAWS PART 1 GENERAL 1. General interpretation 2. Application 3. Opening times PART 2 PROTECTION OF THE GROUND, ITS WILDLIFE AND THE PUBLIC 4. Protection of structures and plants 5. Unauthorised erection of structures 6. Climbing 7. Grazing 8. Protection of wildlife 9. Fires 10. Missiles 11. Interference with life-saving equipment PART 3 HORSES AND CYCLES 12. Horses 13. Cycling PART 4 PLAY AREAS, GAMES AND SPORTS 14. Interpretation of Part 4 15. Children’s play areas 16. Children’s play apparatus 17. Skateboarding, etc 18. Cricket 19. Archery 20. Field sports 21. Golf PART 5 WATERWAYS 22. Interpretation of Part 5 23. Bathing 24. Ice skating 25. Boats 26. Fishing 27. Pollution 28. Blocking of watercourses PART 6 MODEL AIRCRAFT 29. Interpretation of Part 6 30. Model aircraft PART 7 OTHER REGULATED ACTIVITIES 31. Provision of services 32. Excessive noise 33. Aircraft, hang-gliders and hot air balloons 34. Kites PART 8 MISCELLANEOUS 35. Obstruction 36. Savings 37. Removal of offenders 38. Penalty 39. Revocation SCHEDULE 1 - Grounds to which byelaws apply generally SCHEDULE 2 - Grounds referred to in certain byelaws 2 Byelaws made under section 164 of the Public Health Act 1875 and sections 12 and 15 of the Open Spaces Act 1906 by the London Borough of Southwark with respect to pleasure grounds, public walks and open spaces. PART 1 GENERAL General Interpretation 1. In these byelaws: “the Council” means the London Borough of Southwark; “the -

The Campaign to Abolish Imprisonment for Debt In

THE CAMPAIGN TO ABOLISH IMPRISONMENT FOR DEBT IN ENGLAND 1750 - 1840 A thesis submitted in partial f'ulf'ilment of' the requirements f'or the Degree of' Master of' Arts in History in the University of' Canterbury by P.J. LINEHAM University of' Canterbury 1974 i. CONTENTS CHAPI'ER LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES • . ii PREFACE . • iii ABSTRACT . • vii ABBREVIATIONS. • •• viii I. THE CREDITOR'S LAW • • • • . • • • • 1 II. THE DEBTOR'S LOT • • . • • . 42 III. THE LAW ON TRIAL • • • • . • . • • .. 84 IV. THE JURY FALTERS • • • • • • . • • . 133 v. REACHING A VERDICT • • . • . • 176 EPILOGUE: THE CREDITOR'S LOT . 224 APPENDIX I. COMMITTALS FOR DEBT IN 1801 IN COUNTY TOTALS ••••• • • • • • 236 II. SOCIAL CLASSIFICATION OF DEBTORS RELEASED BY THE COURT, 1821-2 • • • 238 III. COMMITTALS FOR DEBT AND THE BUSINESS CLIMATE, 1798-1818 . 240 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 242 ii. LIST OF TABLES TABLE I. Social Classirication of Debtors released by the Insolvent Debtors Court ••••••••• • • • 50 II. Prisoners for Debt in 1792. • • • • • 57 III. Committals to Ninety-Nine Prisons 1798-1818 •••••••••••• • • 60 IV. Social Classification of Thatched House Society Subscribers • • • • • • 94 v. Debtors discharged annually by the Thatched House Society, 1772-1808 ••••••••••• • • • 98 VI. Insolvent Debtors who petitioned the Court • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 185 LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE ~ I. Committals for Debt in 1801. • • • • • 47 II. Debtors and the Economic Climate •••••••• • • • • • • • 63 iii. PREFACE Debtors are the forgotten by-product of every commercial society, and the way in which they are treated is often an index to the importance which a society attaches to its commerce. This thesis examines the English attitude to civil debtors during an age when commerce increased enormously. -

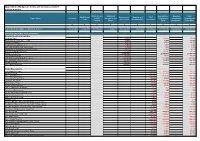

Appendix C - Budget Virements and Variations 2020/21 Outturn Monitor

Appendix C - Budget virements and variations 2020/21 outturn monitor Children's and Southwark General Fund Housing Total Adult Social Environment Housing and Chief Project Name Children's Adults' Schools for the Programme Investment Programmed Care and Leisure Modernisation Executive's Services Future Total Programme Expenditure £ £ £ £ £ £ £ £ £ £ CURRENT PROGRAMME AT MONTH 8 2020-21 84,503,990 32,947,378 117,451,368 5,489,177 132,103,138 78,645,905 241,018,066 574,707,654 2,093,902,747 2,668,610,401 OUTTURN VIREMENTS TO BE APPROVED Environment and Leisure Peckham Ward (15,000) (15,000) (15,000) Nunhead & Peckham Rye - CGS 15,000 15,000 15,000 Newington Gardens 48,352 48,352 48,352 Peckham Pulse Option 1 & 2 1,500 1,500 1,500 OLF SSG Disability Multi-Sports Court (1,500) (1,500) (1,500) Monuments & Memorials in the Public Realm 27,648 27,648 27,648 Structures Capital Programme (27,648) (27,648) (27,648) Climate Emergency 25,000,000 25,000,000 25,000,000 Enid Street Play Area 49,744 49,744 49,744 OLF SSG Disability Multi-Sports Court (342,000) (342,000) (342,000) OLF Southwark Athletics Centre 342,000 342,000 342,000 Bevington Street 55,755 55,755 55,755 Community Playspaces 669,693 669,693 669,693 - - Chief Executive's Enid Street Play Area (49,744) (49,744) (49,744) Bevington Street (55,755) (55,755) (55,755) Community Playspaces (669,693) (669,693) (669,693) Grove Lane Pocket Place 53,465 53,465 53,465 Lordship Lane Traffic (46,940) (46,940) (46,940) Demonstrator Zones (34,100) (34,100) (34,100) Deliver Walking Network 19,108 19,108 -

Imprisoned Debtors

RESEARCH GUIDE 66 - Imprisoned Debtors CONTENTS Introduction Records of Debtors Records of Bankrupts Reading List Introduction By the 14th century all creditors could cause those owing them money to be committed to prison to try to secure the payment of their debts. Before 1841 the legal status of being a bankrupt and therefore able to pay off creditors and be discharged of all outstanding debts was confined to traders owing more than £100. Many debtors who were not traders or who owed less than £100 were confined indefinitely in prison, responsible for their debts but unable to pay them. They were often held in the same prisons as those remanded for trial and convicted offenders and formed one of the largest groups of prisoners. In 1776 John Howard found that 2,437 out of a total of 4,084 inmates were imprisoned for debt. Until 1869 debtors were allowed extensive privileges compared to other prisoners, including being allowed visitors, their own food and clothing, and the right to work at their trade or profession as far as was possible in prison. Periodic Acts of Parliament (37 between 1670 and 1800) for the Relief of Insolvent Debtors allowed the release of debtors from prison if they applied to a Justice of the Peace and submitted a schedule of their assets. In 1813 a Court for the Relief of Insolvent Debtors was established. The 1844 Insolvency Act abolished imprisonment for debts under £20 and allowed private persons to become bankrupts and lowered the financial limit to £50. The 1861 Bankruptcy Act abolished the Court for the Relief of Insolvent Debtors and transferred its jurisdiction to the Bankruptcy Court. -

Venues of Popular Politics in London, 1790–C. 1845

Bibliography Primary sources Archival sources Arundel Castle Archives ACC2 Strand Estate Papers AC MSS, Howard Letters and Papers, 1636–1822, II Bishopsgate Institute Papers of George J. Holyoake British Library Francis Place Papers Correspondence of Leigh Hunt City of Westminster Archives Foster, D. Inns, Tavern, Alehouses, Coffee Houses etc, In and Around London, vol. 20, c. 1900. Guildhall Library Collection Nobel Collection: Surrey Institution Papers. Norman Collection: Collection of newspaper and other cuttings related to London inns, taverns, coffeehouses, clubs, tea gardens, music halls, c.1885–1900, 5 vols. Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino, California Richard Carlile Papers London Metropolitan Archives Rendle Collection, Southwark File 287 Radical Spaces Middlesex Sessions of the Peace Papers Public Record Office Home Office Papers HO40/20-25 British Nineteenth Century Riots and Disturbances. HO64 Discontent and Authority in England 1820–40. HO64/11 Police and Secret Service Reports, 1827–1831, Police and Secret Service Reports, reports from Stafford of Seditious Meetings, Libellous Papers, 1830–33. HO64/12 Police and Secret Service Reports, 1832. HO64/13 Secret Service Miscellaneous Reports and Publications HO64/15 Reports 1834–37. HO64/16 Reports and Miscellaneous, 1827–33. HO64/17 Police and Secret Service Reports, 1831. HO64/18 Seditious Publications, 1830–36. Southwark Local Studies Library Surrey Institution/Rotunda Collection Wellcome Library ‘Surrey Rotunda’ Collection, 1784–1858. West Yorkshire Archive Service, Leeds Humphrey Boyle Papers Contemporary newspapers and periodicals Bell’s Life in London, 14 July 1822. Bell’s Weekly Messenger, 14 November 1830. Black Dwarf, 1820–24, selected dates. Cobbett’s Weekly Political Register, 1816–30, selected dates.