Pretrial Detention, Release, and Bail Practice in Oregon (2021)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taking Notae on King and Cleric: Thibaut, Adam, and the Medieval Readers of the Chansonnier De Noailles (T-Trouv.)

_full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien B2 voor dit chapter en nul 0 in hierna): 0 _full_alt_articletitle_running_head (oude _articletitle_deel, vul hierna in): Taking Notae on King and Cleric _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 Taking Notae On King And Cleric 121 Chapter 5 Taking Notae on King and Cleric: Thibaut, Adam, and the Medieval Readers of the Chansonnier de Noailles (T-trouv.) Judith A. Peraino The serpentine flourishes of the monogram Nota in light brown ink barely catch the eye in the marginal space beside a wide swath of much darker and more compact letters (see Figure 5.1). But catch the eye they do, if not in the first instance, then at some point over the course of their fifty-five occurrences throughout the 233 folios of ms. T-trouv., also known as the Chansonnier de Noailles.1 In most cases the monogram looks more like Noā – where the “a” and the “t” have fused into one peculiar ligature. Variations of the monogram indi- cate a range of more or less swift and continuous execution (see Figure 5.2), but consistency in size and ink color strongly suggest the work of a single an- notator. Adriano Cappelli’s Dizionario di abbreviature latine ed italiane includes a nearly exact replica of this scribal shorthand for nota, which he dates to the thirteenth century.2 Thus the notae, and the act of reading they indicate, took place soon after its compilation in the 1270s or 1280s. Ms. T-trouv. conveys the sense of a carefully compiled, ordered, and execut- ed compendium of writings, some designed with music in mind, others not. -

Blue Line – Appendices

APPENDIX A IndyGo Public Involvement Program indygo may 2015 www.IndyGo.net public involvement program 317.635.3344 purpose and objectives +"ƛ" 1&3"-2)& &+3,)3"*"+1-/,$/*-/,3&!"0#,/+,-"+"5 %+$",#&+#,/*1&,++!&!"0 "14""+1%"-2)& +!1/+0-,/11&,+!" &0&,+*("/0ǽ%",'" 1&3",# +!6 ,ȉ0-2)& &+3,)3"*"+1 -/, "00&01,02--,/1-/, 1&3"-2)& &+3,)3"*"+11))01$"0,#-)++&+$+!-/,'" 1!"3"),-*"+1ǽ +!6 ,0""(0-2)& #""! (,+3/&"16,#!" &0&,+0Ǿ&+ )2!&+$ǿ ș"/3& "+! /"%+$"0 ș++2)-"/1&+$2!$"1 ș&1)" /")1"!-,)& 6!"3"),-*"+1 %1&*"!" &0&,+0+""!1,"*!",+,+",#1%"0"&1"*0Ǿ +!6 ,4&))21&)&7"&10-2)& &+3,)3"*"+1 -/,$/*1,"+02/"&1&0*""1&+$1%"0"-"/#,/*+ ",'" 1&3"0Ǿ"0-" &))6&+ ,+0&!"/1&,+,#),4&+ ,*" +!*&+,/&16-,-2)1&,+0ǿ ș/)6+! ,+1&+2,20&+3,)3"*"+1 ș"0,+)"-2)& 3&)&)&16,#1" %+& )&+#,/*1&,+ ș,)),/1&3"&+-21,+)1"/+1&3"0Ǿ"3)21&,+ /&1"/&+!*&1&$1&,++""!0 ș-"+-2)& *""1&+$0 ș "001,1%"!" &0&,+Ȓ*(&+$-/, "00-/&,/1, ),02/" affected public and stakeholders +!6 ,01/&3"01,/" %*+62!&"+ "0&+&10-2)& ,21/" %+!"+$$"*"+101/1"$&"0ǽ ,/ " %&+!&3&!2)-)+Ǿ-/,'" 1,/-/,$/*1%1 ))0#,/-2)& &+3,)3"*"+1Ǿ +!6 ,4&))&!"+1=%" 01("%,)!"/04%,/""&1%"/!&/" 1)6,/&+!&/" 1)6ƛ" 1"!ǽ%,0"4%,*6"!3"/0")6ƛ" 1"!,/4%, *6"!"+&"!"+"Ɯ1,#-)+Ǿ-/,'" 1,/-/,$/*/",#-/1& 2)/&+1"/"01&+1%"&!"+1&Ɯ 1&,+,# 01("%,)!"/0ǽ +!6 ,ȉ001("%,)!"/0&+ )2!"Ǿ21/"+,1)&*&1"!1,ǿ ș +!6 ,&!"/0 ș&+,/&16,-2)1&,+0 ș&*&1"!+$)&0%/,Ɯ &"+ 6țȜ,-2)1&,+0 ș,4Ȓ + ,*",-2)1&,+0 ș%,0"4&1%&0&)&1&"0 ș"&$%,/%,,!00, &1&,+0 ș%"&16,# +!&+-,)&0"!"/0%&- ș +!&+-,)&0&16Ȓ,2+16,2+ &) ș1%"//"$&,+)+!*2+& &-)1/+0&1-/,3&!"/0&+ )2!&+$ǿ,**21"/,++" 1Ǿ %211)" "/3& "0Ǿ 36" %%211)""/3& "0Ǿ -

The Crisis of English Wool and Textile Trade Revisited, C. 1275–1330† ∗ by PHILIP SLAVIN

Economic History Review, 73, 4 (2020), pp. 885–913 Mites and merchants: the crisis of English wool and textile trade revisited, c. 1275–1330† ∗ By PHILIP SLAVIN On the basis of 7,871 manorial accounts from 601 sheep-rearing demesnes and 187 tithe receipts from 15 parishes, this article addresses the origins, scale, and impact of the wool and textile production crisis in England, c. 1275–1350. The article argues that recurrent outbreaks of scab disease depressed sheep population and wool production levels until the early 1330s. The disease, coupled with warfare and taxation, also had a decisive role in depressing the volumes of wool exports. Despite this fact, wool merchants were still conducting business with major wool producers, who desperately needed access to the capital to replenish their flocks. he question of the ‘late medieval crisis’ has long puzzled historians. The essence T of the crisis can be summarized as follows. After two centuries of growth and expansion, English and other European economies had reached a phase of decline and/or stagnation, in terms of both aggregate output and per capita income. For a long time, the commonplace interpretations were either demographic or endogenous (technological, institutional, or monetary). For instance, in dealing with the ‘English urban textile crisis’, spanning from the late thirteenth century into the c. 1340s, historians focused on such endogenous factors as the shift of textile production from towns to the countryside, competition with higher quality Flemish and Brabantine cloth imports, technological advantages of the textile industry in the Low Countries, and rising transaction costs linked to ongoing international warfare and the increased burden of taxation.1 However, one exogenous variable that has altogether been overlooked by scholars is the supply of raw material, namely wool, without which nothing worked. -

{Download PDF} Right Here with You: Bringing Mindful

RIGHT HERE WITH YOU: BRINGING MINDFUL AWARENESS INTO OUR RELATIONSHIPS Author: Andrea Miller,Editors of the Shambhala Sun Number of Pages: 288 pages Published Date: 19 Aug 2011 Publisher: Shambhala Publications Inc Publication Country: Boston, United States Language: English ISBN: 9781590309049 DOWNLOAD: RIGHT HERE WITH YOU: BRINGING MINDFUL AWARENESS INTO OUR RELATIONSHIPS Right Here with You: Bringing Mindful Awareness into Our Relationships PDF Book In rare cases, an imperfection in the original, such as a blemish or missing page, may be replicated in our edition. Psychologists, clinical social workers, mental health counselors, psychotherapists, and students and trainees in these areas will find this book useful in learning to apply rational-emotive behavior therapy in practice. Climb aboard with us as we discover these fascinating trains made between 1946 and 1966, which have provided a long-lasting legacy from The A. Boggs, a young artist with a certain panache, a certain flair, an artist whose consuming passion is money, or perhaps, more precisely, value. Michael Miller makes it easy to tweak Windows so it works just like you want it to-and runs smooth as silk for years to come. Example sentences provide contextual support for more in depth understanding and practical application and stories challenge learners with the application of language with follow-up comprehension questions designed to coax them to use the target language. Because there are ways to work together, through open and direct communication, and, most of all, through empathy, to improve any relationship that's not as perfect as it could be. ) a Needed Thing Carried Around Everywhere; A Useful Handbook or Guidebook Always Kept on One's Person; Lit. -

February 15, 2021 Dear Participants in The

Thomas J. McSweeney Robert and Elizabeth Scott Research Professor of Law P.O. Box 8795 Williamsburg, VA 23187-8795 Phone: 757-221-3829 Fax: 757-221-3261 Email: [email protected] February 15, 2021 Dear Participants in the Columbia Legal History Workshop: I am delighted to have the opportunity to present Writing the Common Law in Latin in the Later Thirteenth Century to you. I wanted to give you some context for this project. I’m interested in treatise-writing as a practice. Why do people choose to write treatises? I published my first book, Priests of the Law, a little over a year ago. Priests of the Law is about Bracton, a major treatise of the early to mid-thirteenth century. I have now moved on to a project on the later thirteenth century. A number of (mostly shorter) tracts on the common law survive from the period between about 1260 and 1300. These texts are some of the earliest evidence we have for the education of the lawyers who practiced in the English royal courts. Some even appear to be derived from lecture courses on the common law that we otherwise known nothing about. And yet many of them have never been edited. I have begun to edit and translate some of these texts. As I have been working my way through them, I have been looking for connections and trying to make sense of some of the oddities I have been finding in these texts. This paper is my attempt to make sense of the differences in language I have found. -

F1964.9 Documentation

Freer Gallery of Art \) Smith sonian ` Freer Gallery of Art and Completed: 05 December 2007 F1964.9 Arthur M. Sack/er Gallery Updated: 08 June 2009 (format/bibliography) Artist: Anonymous Title: Master Clam Catches a Shrimp1 《蜆子捕蝦圖 》 Xianzi buxia tu Dynasty/Date: Southern Song, mid-13th century Format: Hanging scroll mounted on panel Medium: Ink on paper Dimensions: 74.6 x 27.9 cm (29-3/8 x 11 in) Credit line: Purchase Accession no.: F1964.9 Provenance: Nathan V. Hammer, New York Accoutrements: 1. New wooden box, with lid inscribed on exterior by unknown hand. Plus text written on inside of lid by Tayama Hōnan 田山方南 (1903–1980), dated 1963, with two (2) seals. Plus printed sticker on one end of N.V. Hammer, Far Eastern Art, New York, with handwritten number. 2. Old wooden (outer) box and lid, with metal lock and hinge at ends. Bad worm damage to lower right side. a. lid inscribed in standard script by Kobori Enshū 小堀遠州 (1579–1647), with three attached paper slips (two effaced) b. paper authentication slip by unidentified writer affixed inside lid, with one (1) seal on wood c. inscribed paper tags affixed to both ends of box. 1 Freer Gallery of Art \) Smith sonian ` Freer Gallery of Art and Completed: 05 December 2007 F1964.9 Arthur M. Sack/er Gallery Updated: 08 June 2009 (format/bibliography) 3. Old wooden (inner) box, with lid inscribed on exterior in clerical-standard script by unknown hand. 4. Cloth wrapper, with paper tag affixed on one end. Painting description: No artist inscription, signature or seal. -

Individual Research in Manuscript Studies

Individual research in manuscript studies Patrons and Artists at the Crossroads: The Islamic Arts of the Book in the Lands of Rūm, 1270s–1370s Cailah Jackson, University of Oxford My doctoral dissertation, submitted to the University of Oxford in 2017 under the supervision of Zeynep Yürekli-Görkay, is the first book-length study to analyse the production and patronage of Islamic illuminated manuscripts in late medieval Rūm in their fullest cultural contexts and in relation to the arts of the book of neighbouring regions. Although research concerning the artistic landscapes of late medieval Rūm has made significant progress in recent years, the development of the arts of the book and the nature of their patronage and production has yet to be fully addressed. The topic also remains relatively ne- glected in the wider field of Islamic art history. This thesis considers the arts of the book and the part they played in artistic life within contemporary scholarly frameworks that emphasise inclusivity, diversity and fluidity. Such frameworks acknowledge the period’s ethnic and religious pluralism, the extent of cross- cultural exchange, the region’s complex political situation after the breakdown in Seljuk rule, and the itinerancy of scholars, Sufis and craftsmen. Analyses are based on the codicological examination of sixteen illumi- nated Persian and Arabic manuscripts, none of which have been published in depth. In order to appropriately assess the material and to partially redress scholarly emphases on the constituent arts of the book (calligraphy, illumina- tion, illustration and binding), the manuscripts are considered as whole ob- jects. The manuscripts’ ample inscriptions (e.g. -

14. Explanation and Definition in Thomas Aquinas' Commentary On

14. Explanation AND DEFINITION IN THOMAS Aquinas’ COMMENTARY ON ARISTOTLE’s METAPHYSICS Fabrizio Amerini In his forty-year career, Sten Ebbesen has dealt with a great number of medieval topics, and metaphysics has not escaped his notice. In a series of texts that, in recent years, Sten has published in the Cahiers de l’Institut du Moyen-Âge Grec et Latin and elsewhere, he has, among other things, directed the attention of scholars to the presence of sensitive logical and semantical issues in the commentary tradition on Aristotle’s Metaphysics.1 In this paper I want to continue this line of investigation and focus on the interconnection between logic and metaphysics. I will not, however, approach this issue from the usual perspective of the relation between these two sciences—their borders, methods and subject-matter. My con- cern, rather, is to discuss the contribution that (syllogistic) logic can give to metaphysics, that is, the role that it can play in a metaphysical explana- tion of natural phenomena. Since the medievals normally read Aristotle’s Metaphysics as a work applying the Posterior Analytics theory of science to the field of metaphysics, (syllogistic) logic is supposed to structure the way of doing investigation in metaphysics. An interesting example of such an interconnection is given by Metaphysics 7.17, the chapter where, according to some contemporary interpreters, Aristotle extends the Posterior Analy- tics explanation theory from attributes to substances. The present paper deals with Thomas Aquinas’s interpretation of this chapter. 1 See, e.g., S. Ebbesen, ‘Words and Signification in 13th-Century Questions on Aristotle’s Metaphysics’, CIMAGL 71 (2000), 71–114, and S. -

Calendars of the United States House of Representatives and History of Legislation

1 ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS CONVENED JANUARY 3, 2019 FIRST SESSION ! ! CALENDARS OF THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES AND HISTORY OF LEGISLATION LEGISLATIVE DAY 176 CALENDAR DAY 176 Thursday, December 5, 2019 HOUSE MEETS AT 10 A.M. FOR MORNING-HOUR DEBATE E PL UR UM IB N U U S SPECIAL ORDERS (SEE NEXT PAGE) www.HouseCalendar.gov PREPARED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF CHERYL L. JOHNSON, CLERK OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES: By the Office of Legislative Operations The Clerk shall cause the calendars of the House to be Index to the Calendars will be included on the first legislative day of distributed each legislative day. Rule II, clause 2(e) each week the House is in session U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE : 2019 99–038 2 SPECIAL ORDERS SPECIAL ORDER The Speaker’s policy with regard to special-order speeches announced on February 11, SPEECHES 1994, as clarified and reiterated by subsequent Speakers, will continue to apply in the 116th Congress, with the following modifications. The Chair may recognize Members for special-order speeches for up to 4 hours. Such speeches may not extend beyond the 4-hour limit without the permission of the Chair, which may be granted only with advance consultation between the leader- ships and notification to the House. However, the Chair will not recognize for any special-order speeches beyond 10 o’clock in the evening. The 4-hour limitation will be divided between the majority and minority parties. Each party is entitled to reserve its first hour for respective leaderships or their designees. -

1060S 1070S 1080S 1090S 1100S 1110S 1120S 1130S 1140S 1150S

Domesday structure of Allertonshire Traces of the medieval village First edition 1:10560 OS map (1856) Villages where Village pump churches were David Rogers Depiction of Thornton le Street mill on early C18th map The Catholic cemetery affected by Medieval jug found in Area of 6 carucates (Thornton le Street) and at Kilvington Old Hall Scots raids in Thornton le Street in 1980s Wood End: reproduced by permission 7 carucates (North Kilvington) @ 120acres/carucate 1318 of North Yorkshire Library Services East window in St Leonard’s 1783: from Armstrong’s Post roads Church: by Kempe (1894) 1060s 1070s 1080s 1090s 1100s 1110s 1120s 1130s 1140s 1150s 1160s 1170s 1180s 1190s 1200s 1210s 1220s 1230s 1240s 1250s 1260s 1270s 1280s 1290s 1300s 1310s 1320s 1330s 1340s 1350s 1360s 1370s 1380s 1390s 1400s 1410s 1420s 1430s 1440s 1450s 1460s 1470s 1480s 1490s 1500s 1510s 1520s 1530s 1540s 1550s 1560s 1570s 1580s 1590s 1600s 1610s 1620s 1630s 1640s 1650s 1660s 1670s 1680s 1690s 1700s 1710s 1720s 1730s 1740s 1750s 1760s 1770s 1780s 1790s 1800s 1810s 1820s 1830s 1840s 1850s 1860s 1870s 1880s 1890s 1900s 1910s 1920s 1930s 1940s 1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000s 2010s 1042-1066 1066 Harold II 1087 -1100 1100-1135 1135-1154 1154 -1189 1189-1199 1199-1216 1216 -1272 1272-1307 1307-1327 1327 -1377 1377-1399 1399-1413 1413-1422 1422 -1461 1461 -1483 1483 Ed V 1485-1509 1509-1547 1547-1553 1553 Grey 1558 - 1603 1603 -1625 1625-1649 1649-1660 1660 -1685 1685-8 1688-1702 1702-1714 1714 - 1727 1727 -1760 1760-1820 1820-1830 1830-1837 1837-1901 1901-1910 1910 -

Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia Korea and Japan

Maritime History Case Study Guide: Northeast Asia Thirteenth Century Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia Korea and Japan Study Guide Prepared By Eytan Goldstein Lyle Goldstein Grant Rhode Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia: Korea and Japan Study Guide | 2 Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia Korea and Japan Study Guide Contents Decision Point Questions: The following six “Decision Point Questions” (DPQs) span the Mongol actions from 1270 through 1286 in a continuum. Case 1, the initial decision to invade, and Case 6, regarding a hypothetical third invasion, are both big strategic questions. The other DPQs chronologically in between are more operational and tactical, providing a strong DPQ mix for consideration. Case 1 The Mongol decision whether or not to invade Japan (1270) Case 2 Decision to abandon Hakata Bay (1274) Case 3 Song capabilities enhance Mongol capacity at sea (1279) Case 4 Mongol intelligence collection and analysis (1275–1280) Case 5 Rendezvous of the Mongol fleets in Imari Bay (1281) Case 6 Possibility of a Third Mongol Invasion (1283–1286) Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia: Korea and Japan Study Guide | 3 Case 1: The Mongol decision whether or not to invade Japan (1270) Overview: The Mongols during the thirteenth century built a nearly unstoppable war machine that delivered almost the whole of the Eurasian super continent into their hands by the 1270s. These conquests brought them the treasures of Muscovy, Baghdad, and even that greatest prize of all: China. Genghis Khan secured northern China under the Jin early on, but it took the innovations of his grandson Kublai Khan to finally break the stubborn grip of the Southern Song, which they only achieved after a series of riverine campaigns during the 1270s. -

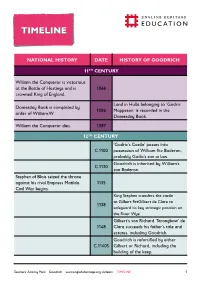

Goodrich-Castle-Timeline.Pdf

TIMELINETIMELINE NATIONAL HISTORY DATE HISTORY OF GOODRICH 11TH CENTURY William the Conqueror is victorious at the Battle of Hastings and is 1066 crowned King of England. Land in Hulla belonging to ‘Godric Domesday Book is completed by 1086 Mappeson’ is recorded in the order of William.W Domesday Book. William the Conqueror dies. 1087 12TH CENTURY ‘Godric’s Castle’ passes into C.1100 possession of William fitz Baderon, probably Godic’s son in law. Goodrich is inherited by William’s C.1120 son Baderon. Stephen of Blois seized the throne against his rival Empress Matilda. 1135 Civil War begins. King Stephen transfers the castle to Gilbert fitzGilbert de Clare to 1138 safeguard its key strategic position on the River Wye. Gilbert’s son Richard ‘Strongbow’ de 1148 Clare succeeds his father’s title and estates, including Goodrich. Goodrich is refortified by either C.1140S Gilbert or Richard, including the building of the keep. Teachers’ Activity Pack Goodrich www.english-heritage.org.uk/learn TIMELINE 1 Matilda’s son Henry II ascends the 1154 throne. Richard Strongbow sails to Ireland as its successful conqueror, in defiance 1170 of royal instructions. Richard Strongbow dies in Dublin. 1176 The Goodrich estate reverts to the Crown. King Richard 1 arranges the marriage of Isabel de Clare, Richard 1189 Strongbow’s daughter, to William Marshal. 13TH CENTURY William Marshall is granted 1204 Goodrich Castle King John agrees to the terms of 1215 Magna Carta. King John dies. At Henry III’s coronation, William William is named by the king's is informed about a Welsh attack 1216 council to serve as protector of the on Goodrich Castle, which he was nine-year-old King Henry III, and forced to repel.