Transparency in CRTC Decision-Making I. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The State of Competition in Canada's Telecommunications

RESEARCH PAPERS MAY 2016 THE STATE OF COMPETITION IN CANADA’S TELECOMMUNICATIONS INDUSTRY – 2016 By Martin Masse and Paul Beaudry The Montreal Economic Institute is an independent, non-partisan, not-for-profi t research and educational organization. Through its publications, media appearances and conferences, the MEI stimu- lates debate on public policies in Quebec and across Canada by pro- posing wealth-creating reforms based on market mechanisms. It does 910 Peel Street, Suite 600 not accept any government funding. Montreal (Quebec) H3C 2H8 Canada The opinions expressed in this study do not necessarily represent those of the Montreal Economic Institute or of the members of its Phone: 514-273-0969 board of directors. The publication of this study in no way implies Fax: 514-273-2581 that the Montreal Economic Institute or the members of its board of Website: www.iedm.org directors are in favour of or oppose the passage of any bill. The MEI’s members and donors support its overall research program. Among its members and donors are companies active in the tele- communications sector, whose fi nancial contribution corresponds to around 4.5% of the MEI’s total budget. These companies had no input into the process of preparing the fi nal text of this Research Paper, nor any control over its public dissemination. Reproduction is authorized for non-commercial educational purposes provided the source is mentioned. ©2016 Montreal Economic Institute ISBN 978-2-922687-65-1 Legal deposit: 2nd quarter 2016 Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec -

An Introduction to Telecommunications Policy in Canada

Australian Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy An Introduction to Telecommunications Policy in Canada Catherine Middleton Ryerson University Abstract: This paper provides an introduction to telecommunications policy in Canada, outlining the regulatory and legislative environment governing the provision of telecommunications services in the country and describing basic characteristics of its retail telecommunications services market. It was written in 2017 as one in a series of papers describing international telecommunications policies and markets published in the Australian Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy in 2016 and 2017. Drawing primarily from regulatory and policy documents, the discussion focuses on broad trends, central policy objectives and major players involved in building and operating Canada’s telecommunications infrastructure. The paper is descriptive rather than evaluative, and does not offer an exhaustive discussion of all telecommunications policy issues, markets and providers in Canada. Keywords: Policy; Telecommunications; Canada Introduction In 2017, Canada’s population was estimated to be above 36.5 million people (Statistics Canada, 2017). Although Canada has a large land mass and low population density, more than 80% of Canadiansi live in urban areas, the majority in close proximity to the border with the United States (Central Intelligence Agency, 2017). Telecommunications services are easily accessible for most, but not all, Canadians. Those in lower-income brackets and/or living in rural and remote areas are less likely to subscribe to telecommunications services than people in urban areas or with higher incomes, and high-quality mobile and Internet services are simply not available in some parts of the country (CRTC, 2017a). On average, Canadian households spend more than $200 (CAD)ii per month to access mobile phone, Internet, television and landline phone services (2015 data, cited in CRTC, 2017a). -

Your World Right Now Rogers Communications Inc. 2004 Annual Report

YOUR WORLD RIGHT NOW ROGERS COMMUNICATIONS INC. 2004 ANNUAL REPORT 1 Your World Right Now 10 Rogers Wireless 11 Rogers Cable 12 Rogers Media 13 Rogers in the Community 14 Rogers at a Glance 15 Letter to Shareholders 18 Management’s Discussion and Analysis 74 Consolidated Financial Statements 77 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements 110 Directors and Corporate Officers 112 Corporate Governance Overview 113 Corporate Information Rogers Communications Inc. (TSX: RCI; NYSE: RG) is a diversified Canadian communications and media company engaged in three primary lines of business: Rogers Wireless is Canada’s largest wireless Rogers Cable is Canada’s largest cable provider Rogers Media owns a collection of well known voice and data communications services provider offering cable television, high-speed Internet Canadian media assets with businesses in radio and the country’s only carrier operating on the access and video retailing, and plans to begin and television broadcasting, televised shopping, world standard GSM/GPRS technology platform. offering cable telephony services in the second publishing and sports entertainment. half of 2005. YOUR WORLD RIGHT NOW™ CHECKING CHECKING PURCHASING WIRELESSLY PACKED FLIGHT OFFICE BLUE JAYS SYNCHING CHATELAINE STATUS VOICEMAIL TICKETS CALENDAR AND FLARE WIRELESSLY ON PDA MAGAZINES FOR FLIGHT LISTENING PURCHASED VACATION PVR ROAMS TO CHFI TICKETS INSPIRED RECORDING GLOBALLY RADIO ONLINE BY TRAVEL FAVOURITE WITH WITH SHOW ON SHOW ROGERS ROGERS™ CABLE AT HOME GSM CELL YAHOO!® PHONE HI-SPEED INTERNET BE INFORMED RIGHT NOW Rogers gives you what you need to make informed decisions in a world of many options. Whether you’re on the go, at your desk or on your couch, we have innovative solutions that deliver the information you need in today’s fast-paced and exciting world. -

New Solar Research Yukon's CKRW Is 50 Uganda

December 2019 Volume 65 No. 7 . New solar research . Yukon’s CKRW is 50 . Uganda: African monitor . Cape Greco goes silent . Radio art sells for $52m . Overseas Russian radio . Oban, Sheigra DXpeditions Hon. President* Bernard Brown, 130 Ashland Road West, Sutton-in-Ashfield, Notts. NG17 2HS Secretary* Herman Boel, Papeveld 3, B-9320 Erembodegem (Aalst), Vlaanderen (Belgium) +32-476-524258 [email protected] Treasurer* Martin Hall, Glackin, 199 Clashmore, Lochinver, Lairg, Sutherland IV27 4JQ 01571-855360 [email protected] MWN General Steve Whitt, Landsvale, High Catton, Yorkshire YO41 1EH Editor* 01759-373704 [email protected] (editorial & stop press news) Membership Paul Crankshaw, 3 North Neuk, Troon, Ayrshire KA10 6TT Secretary 01292-316008 [email protected] (all changes of name or address) MWN Despatch Peter Wells, 9 Hadlow Way, Lancing, Sussex BN15 9DE 01903 851517 [email protected] (printing/ despatch enquiries) Publisher VACANCY [email protected] (all orders for club publications & CDs) MWN Contributing Editors (* = MWC Officer; all addresses are UK unless indicated) DX Loggings Martin Hall, Glackin, 199 Clashmore, Lochinver, Lairg, Sutherland IV27 4JQ 01571-855360 [email protected] Mailbag Herman Boel, Papeveld 3, B-9320 Erembodegem (Aalst), Vlaanderen (Belgium) +32-476-524258 [email protected] Home Front John Williams, 100 Gravel Lane, Hemel Hempstead, Herts HP1 1SB 01442-408567 [email protected] Eurolog John Williams, 100 Gravel Lane, Hemel Hempstead, Herts HP1 1SB World News Ton Timmerman, H. Heijermanspln 10, 2024 JJ Haarlem, The Netherlands [email protected] Beacons/Utility Desk VACANCY [email protected] Central American Tore Larsson, Frejagatan 14A, SE-521 43 Falköping, Sweden Desk +-46-515-13702 fax: 00-46-515-723519 [email protected] S. -

Proceedings of the 6Th Workshop on Vision and Language, Pages 1–10, Valencia, Spain, April 4, 2017

VL 2017 The 6th Workshop on Vision and Language Proceedings of the Workshop April 4, 2017 Valencia, Spain This workshop is supported by ICT COST Action IC1307, the European Network on Integrating Vision and Language (iV&L Net): Combining Computer Vision and Language Processing For Advanced Search, Retrieval, Annotation and Description of Visual Data. c 2017 The Association for Computational Linguistics Order copies of this and other ACL proceedings from: Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL) 209 N. Eighth Street Stroudsburg, PA 18360 USA Tel: +1-570-476-8006 Fax: +1-570-476-0860 [email protected] ISBN 978-1-945626-51-7 ii Introduction The 6th Workshop on Vision and Language 2017 (VL’17) took place in Valencia as part of EACL’17. The workshop is organised by the European Network on Integrating Vision and Language which is funded as a European COST Action. The VL workshops have the general aims: to provide a forum for reporting and discussing planned, ongoing and completed research that involves both language and vision; and to enable NLP and computer vision researchers to meet, exchange ideas, expertise and technology, and form new research partnerships. Research involving both language and vision computing spans a variety of disciplines and applications, and goes back a number of decades. In a recent scene shift, the big data era has thrown up a multitude of tasks in which vision and language are inherently linked. The explosive growth of visual and textual data, both online and in private repositories by diverse institutions and companies, has led to urgent requirements in terms of search, processing and management of digital content. -

Societe Canadienne Pour Les Traditions Musicales

50 51 CONSEIL Bulletin editor) Heather Sparling, 128-833 Scollard Res.: (416) 225-1547 Court, Mississauga, Ont. L5V 2B4 D'ADMINISTRATION/ Email: [email protected] Res.: (905) 501-1459 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Email: [email protected] Maureen Chafe,4512 Charleswood Dr. NW, Calgary, Alta. T2L 2E3 Norman Stanfield, 301 2017 West 5 Ave., Res.: (403) 277-7908; Bus.: 240-8984; Fax: Vancouver, B.C. V6J 1P8 Presidente/President 240-6594(must be addressed to Res. & bus.: (604) 732-6404 Maureen Chafe) Leslie Hall, Dept. of Philosophy & Email: [email protected] Music, Ryerson Polytechnic University, Email: [email protected] 350 Victoria St., Toronto, Ont. Phil Thomas, 4158 West 10th Ave., Anne-Marie Desdouits, Universite M4G 2K3 . Vancouver, B.C. V6R 2H3 Laval, Ethnologie, Departement 21 Berney Cres., Toronto, Ont. Res.: (604) 224-4678 d'histoire, Faculte de lettres, Pavilion M4G 3G4 Email: [email protected] Res.: (416) 485-4545; Bus.: 979-5000, ext. de Koninck, Ste-Foy (Quebec) G1V 7P4 (no attachments) or 7044; Fax: 979-5362 2517, rue Des Plaines, Ste-Foy (Quebec) [email protected] Email: [email protected] G1V 1B2 Res.: (418) 652-8225; Bus.: 656-2131, ext. David Warren, 103 Old Forest Hill Rd., SOCIETE Vice-presidents/Vice-Presidents 7996 Toronto, Ont. M5P 2R8 Email: anne- Res.: (416) 781-3922; Bus.: 763-4183; Fax: CANADIENNE Mike Ballantyne, P.O.B. 312, Cobble [email protected] 763-1310 Hill, B.C. V0R 1L0 Email: [email protected] Res.: (250) 743-3996 Dave Foster, 1516 24th St. NW, Calgary, POUR LES Email: [email protected] Alta. -

I. Tv Stations

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554 In the Matter of ) ) MB Docket No. 17- WSBS Licensing, Inc. ) ) ) CSR No. For Modification of the Television Market ) For WSBS-TV, Key West, Florida ) Facility ID No. 72053 To: Office of the Secretary Attn.: Chief, Policy Division, Media Bureau PETITION FOR SPECIAL RELIEF WSBS LICENSING, INC. SPANISH BROADCASTING SYSTEM, INC. Nancy A. Ory Paul A. Cicelski Laura M. Berman Lerman Senter PLLC 2001 L Street NW, Suite 400 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (202) 429-8970 April 19, 2017 Their Attorneys -ii- SUMMARY In this Petition, WSBS Licensing, Inc. and its parent company Spanish Broadcasting System, Inc. (“SBS”) seek modification of the television market of WSBS-TV, Key West, Florida (the “Station”), to reinstate 41 communities (the “Communities”) located in the Miami- Ft. Lauderdale Designated Market Area (the “Miami-Ft. Lauderdale DMA” or the “DMA”) that were previously deleted from the Station’s television market by virtue of a series of market modification decisions released in 1996 and 1997. SBS seeks recognition that the Communities located in Miami-Dade and Broward Counties form an integral part of WSBS-TV’s natural market. The elimination of the Communities prior to SBS’s ownership of the Station cannot diminish WSBS-TV’s longstanding service to the Communities, to which WSBS-TV provides significant locally-produced news and public affairs programming targeted to residents of the Communities, and where the Station has developed many substantial advertising relationships with local businesses throughout the Communities within the Miami-Ft. Lauderdale DMA. Cable operators have obviously long recognized that a clear nexus exists between the Communities and WSBS-TV’s programming because they have been voluntarily carrying WSBS-TV continuously for at least a decade and continue to carry the Station today. -

Distie's View

DISTIE’S VIEW IN-BUILDING WIRELESS OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE VAR CHANNEL CROSSOVER DISTRIBUTION.COM’S DARIN GIBBONS ON A FIELD THAT IS GROWING AS CELLULAR COMPETITION IN THE CANADIAN MARKET INCREASES by DARIN GIBBONS he wireless industry continues to venues where their return on investment is greater. They offer experience significant growth as these types of solutions to certain enterprise customers that meet the enterprise and consumer worlds their Average Revenue Per User (ARPU) metrics but unfortunately want the flexibility of always being they are just not able to address all in-building coverage gaps due Tconnected but not necessarily connected by a to budget constraints. wired infrastructure. The ever growing need The VAR can play a significant role in addressing these wireless for mobility, coupled with exploding sales of Smart Phones and in-building coverage issues for their enterprise customers by their countless new applications, are they key reasons for this educating them on their options and ultimately providing them unprecedented growth. with a solution. Mobility Service Providers are working diligently to expand Simple solutions known as adaptive repeaters extend the their macro and back office networks to meet these demands. 3G outdoor cellular network into the building without requiring Networks, 4G Networks, High Speed Packet Access ( HSPA ) and changes to the service providers’ macro network. They often Long-Term Evolution ( LTE ) are some of the terms that the general consist of a rooftop mounted antenna with coaxial cable feeding public often reads about on the internet and through various into the building which is then connected to indoor coverage service provider media campaigns that will facilitate this wireless units or antennas to distribute the cellular signals. -

FACTOR 2006-2007 Annual Report

THE FOUNDATION ASSISTING CANADIAN TALENT ON RECORDINGS. 2006 - 2007 ANNUAL REPORT The Foundation Assisting Canadian Talent on Recordings. factor, The Foundation Assisting Canadian Talent on Recordings, was founded in 1982 by chum Limited, Moffat Communications and Rogers Broadcasting Limited; in conjunction with the Canadian Independent Record Producers Association (cirpa) and the Canadian Music Publishers Association (cmpa). Standard Broadcasting merged its Canadian Talent Library (ctl) development fund with factor’s in 1985. As a private non-profit organization, factor is dedicated to providing assistance toward the growth and development of the Canadian independent recording industry. The foundation administers the voluntary contributions from sponsoring radio broadcasters as well as two components of the Department of Canadian Heritage’s Canada Music Fund which support the Canadian music industry. factor has been managing federal funds since the inception of the Sound Recording Development Program in 1986 (now known as the Canada Music Fund). Support is provided through various programs which all aid in the development of the industry. The funds assist Canadian recording artists and songwriters in having their material produced, their videos created and support for domestic and international touring and showcasing opportunities as well as providing support for Canadian record labels, distributors, recording studios, video production companies, producers, engineers, directors– all those facets of the infrastructure which must be in place in order for artists and Canadian labels to progress into the international arena. factor started out with an annual budget of $200,000 and is currently providing in excess of $14 million annually to support the Canadian music industry. Canada has an abundance of talent competing nationally and internationally and The Department of Canadian Heritage and factor’s private radio broadcaster sponsors can be very proud that through their generous contributions, they have made a difference in the careers of so many success stories. -

PPM Top-Line Radio Statistics Montreal CTRL Anglo

PPM Top-line Radio Statistics Montreal CTRL Anglo Broadcast year: Radio Meter 2019-2020 Survey period: August 26, 2019 - November 24, 2019 Demographic: A12+ Daypart: Monday to Sunday 2am-2am Geography: Montreal CTRL Anglo Data type: Respondent August 26, 2019 - November 24, 2019 Average Daily Universe: 849,000 Station Market AMA (000) Daily Cume (000) Share (%) CBFFM Montreal CTRL Anglo 0.7 15.2 1.4 CBFXFM Montreal CTRL Anglo 0.1 8.2 0.3 CBMFM Montreal CTRL Anglo 1.2 22.3 2.4 CBMEFM Montreal CTRL Anglo 3.3 53.5 6.9 CFGLFM Montreal CTRL Anglo 1.1 54.3 2.3 CHMPFM Montreal CTRL Anglo 1.2 32.4 2.4 CHOMFM Montreal CTRL Anglo 5.2 121.4 10.8 CHRF Montreal CTRL Anglo 0.0 1.7 0.0 CITEFM Montreal CTRL Anglo 0.5 31.8 1.0 CJAD Montreal CTRL Anglo 12.2 162.7 25.3 CJFMFM Montreal CTRL Anglo 4.5 145.9 9.4 CKAC Montreal CTRL Anglo 0.1 3.4 0.1 CKBEFM Montreal CTRL Anglo 10.3 229.9 21.5 CKGM Montreal CTRL Anglo 2.0 49.7 4.1 CKLXFM Montreal CTRL Anglo 0.1 5.8 0.2 CKMFFM Montreal CTRL Anglo 1.2 27.6 2.6 CKOIFM Montreal CTRL Anglo 0.5 39.8 1.0 TERMS Average Minute Audience (000): Expressed in thousands, this is the average number of persons exposed to a radio station during an average minute. Calculated by adding all the individual minute audiences together and dividing by the number of minutes in the daypart. -

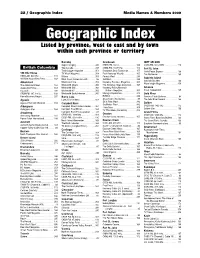

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

New Zealand DX Times Monthly Journal of the D X New Zealand Radio DX League (Est 1948) D X April 2013 Volume 65 Number 6 LEAGUE LEAGUE

N.Z. RADIO N.Z. RADIO New Zealand DX Times Monthly Journal of the D X New Zealand Radio DX League (est 1948) D X April 2013 Volume 65 Number 6 LEAGUE http://www.radiodx.com LEAGUE NZ RADIO DX LEAGUE 65TH ANNIVERSARY REPORT AND PHOTOS ON PAGE 36 AND THE DX LEAGUE YAHOO GROUP PAGE http://groups.yahoo.com/group/dxdialog/ Deadline for next issue is Wed 1st May 2013 . P.O. Box 39-596, Howick, Manukau 2145 Mangawhai Convention attendees CONTENTS FRONT COVER more photos page 34 Bandwatch Under 9 4 with Ken Baird Bandwatch Over 9 8 with Kelvin Brayshaw OTHER English in Time Order 12 with Yuri Muzyka Shortwave Report 14 Mangawhai Convention 36 with Ian Cattermole Report and photos Utilities 19 with Bryan Clark with Arthur De Maine TV/FM News and DX 21 On the Shortwaves 44 with Adam Claydon by Jerry Berg Mailbag 29 with Theo Donnelly Broadcast News 31 with Bryan Clark ADCOM News 36 with Bryan Clark Branch News 43 with Chief Editor NEW ZEALAND RADIO DX LEAGUE (Inc) We are able to accept VISA or Mastercard (only The New Zealand Radio DX League (Inc) is a non- for International members) profit organisation founded in 1948 with the main Contact Treasurer for more details. aim of promoting the hobby of Radio DXing. The NZRDXL is administered from Auckland Club Magazine by NZRDXL AdCom, P.O. Box 39-596, Howick, The NZ DX Times. Published monthly. Manukau 2145, NEW ZEALAND Registered publication. ISSN 0110-3636 Patron Frank Glen [email protected] Printed by ProCopy Ltd, President Bryan Clark [email protected] Wellington Vice President David Norrie [email protected] http://www.procopy.co.nz/ © All material contained within this magazine is copy- National Treasurer Phil van de Paverd right to the New Zealand Radio DX League and may [email protected] not be used without written permission (which is here- by granted to exchange DX magazines).