Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Spring 5-17-2019 Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States Margaret Thoemke [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Thoemke, Margaret, "Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 167. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/167 This Thesis (699 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language May 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota iii Copyright 2019 Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke iv Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my three most favorite people in the world. To my mother, Heather Flaherty, for always supporting me and guiding me to where I am today. To my husband, Jake Thoemke, for pushing me to be the best I can be and reminding me that I’m okay. Lastly, to my son, Liam, who is my biggest fan and my reason to be the best person I can be. -

PDF of This Issue

Patriots Win Super Bowl! MIT’s The Weather Oldest and Largest Today: Rain and snow 40°F (4°C) Tonight: Rain, 30s°F (0-3°C) Newspaper Tomorrow: Partly cloudy, 42°F (6°C) Details, Page 2 Volume 124, Number 1 Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Tuesday, February 3, 2004 UA Completes Under Convertible Wins Killian Chaos By Kathleen Dobson year’s Autonomous Design Robot ble Trouble,” created by Cheng Lui Half Of Fall Projects Competition (6.270) called “Killian ’05, Pedro Yip ’05, and Sheung Yan In a nearly full Kresge auditori- Chaos.” S. Lee ’07, by just one point. By Lauren E. LeBon amount has been small. um, “ZSR Convertible,” created by The closest match-up of the day “We expected to go pretty far” and Tongyan Lin “It’s supposed to be a two-way Xin David Zhang ’06, Yasuhiro Shi- for “ZSR Convertible” came in the but did not expect to win, Ren said STAFF REPORTERS thing,” Uzamere said, “not a dic- rasaki ’06, and Yin Ren ’06, went final round of the best of three afterwards. Out of the 52 Undergraduate tum.” undefeated last Thursday to win this match-up, when it defeated “Hum- Having no previous robot design Association’s goals published in While 19 of the goals have been experience and little electronics The Tech last term, 19 have reached completed as of Feb. 1, 23 goals coursework, the “ZSR Convertible” completion by the end of Indepen- have missed the original deadlines team relied on the programming dent Activities Period, while 23 published in The Tech. -

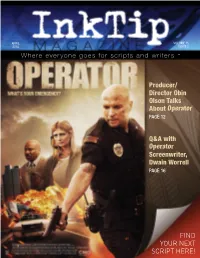

Producer/ Director Obin Olson Talks About Operator PAGE 12

APRIL VOLUME 15 2015 ISSUE 2 Where everyone goes for scripts and writers ™ Producer/ Director Obin Olson Talks About Operator PAGE 12 Q&A with Operator Screenwriter, Dwain Worrell PAGE 16 FIND YOUR NEXT SCRIPT HERE! Where everyone goes for writers and scripts™ IT’S FAST AND EASY TO FIND THE SCRIPT OR WRITER YOU NEED. WWW.INKTIP.COM A FREE SERVICE FOR ENTERTAINMENT PROFESSIONALS. Peruse this magazine, find the scripts/books you like, and go to www.InkTip.com to search by title or author for access to synopses, resumes and scripts! l For more information, go to: www.InkTip.com. l To register for access, go to: www.InkTip.com and click Joining InkTip for Entertainment Pros l Subscribe to our free newsletter at http://www.inktip.com/ep_newsletters.php Note: For your protection, writers are required to sign a comprehensive release form before they can place their scripts on our site. Table of Contents Recent Successes 3, 9, 11 Feature Scripts – Grouped by Genre 7 Industry Endorsements 3 Feature Article: Operator 12 Contest/Festival Winners 4 Q&A: Operator Screenwriter Dwain Worrell 16 Writers Represented by Agents/Managers 4 Get Your Movie on the Cover of InkTip Magazine 18 Teleplays 5 3 Welcome to InkTip! The InkTip Magazine is owned and distributed by InkTip. Recent Successes In this magazine, we provide you with an extensive selection of loglines from all genres for scripts available now on InkTip. Entertainment professionals from Hollywood and all over the Bethany Joy Lenz Options “One of These Days” world come to InkTip because it is a fast and easy way to find Bethany Joy Lenz found “One of These Days” on InkTip, great scripts and talented writers. -

Invictus This Is a Poem 'Invictus' (Unconquered, Undefeated) by William Henley

Invictus This is a Poem 'Invictus' (Unconquered, Undefeated) by William Henley. Nelson Mandela was inspired by the poem, and had it written on a scrap of paper in his prison cell while he was incarcerated for 27 years on Robben Island. Text Out of the night that covers me, Black as the pit from pole to pole, I thank whatever gods may be For my unconquerable soul. In the fell clutch of circumstance I have not winced nor cried aloud. Under the bludgeonings of chance My head is bloody, but unbowed. Beyond this place of wrath and tears Looms but the Horror of the shade, And yet the menace of the years Finds and shall find me unafraid. It matters not how strait the gate, How charged with punishments the scroll, I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul. "Invictus" is a short Victorian poem by the English poet William Ernest Henley (1849– 1903). It was first published in 1875 in a book called Book of Verses, where it was number four in several poems called Life and Death (Echoes). It originally had no title. ... Background At the age of 12, Henley contracted tuberculosis of the bone. A few years later, the disease progressed to his foot, and physicians announced that the only way to save his life was to amputate directly below the knee. It was amputated when he was 17. Stoicism inspired him to write this poem. Despite his disability, he survived with one foot intact and led an active life until his death at the age of 53. -

One Tree Hill the Road Mix Tracklist

One tree hill the road mix tracklist The Road Mix: Music from the Television Series One Tree Hill, Volume 3, the third soundtrack compiled of music featured on the teen drama One Tree Hill was. Listen to songs from the album The Road Mix: Music from the Television Series One Tree Hill, Vol. 3, including "Stay Away", "You'll Ask for Me". Product Description. For the first time in television history, a mixtape heard in an episode will become a soundtrack album. Containing hits from artists such as. One Tree Hill Soundtrack – The Road Mix: Music From The Television Series One Tree Hill Vol. 3. By Mia Hytönen. 16 songs. Play on Spotify. 1. Don't. Tracklist Since One Tree Hill debuted in , the cult-favorite teen drama has become more watchable and complex with each season -- and, judging by 3: The Road Mix, it's also developed more eclectic taste in music. music from the WB television series ONE TREE HILL Music from Website: Volume III: The Road Mix. Music of One Tree Hill. 2-HOUR SERIES FINALE EVENT: One Tree Hill AIRING: Wednesday . Go ahead and pick which characters playlist you wanna mix! Music by Episode: Season One. SEASON ONE: Fall - Spring . The Road Mix: Music From The Television Series 'One Tree Hill' - Volume, 'One Tree. All songs from the tv show, ONE TREE HILL, with scene descriptions, by episode. The Road Mix: Music from the Television Series One Tree Hill, Vol. 3. Blame it on my top 20 songs featured on One Tree Hill. in season 5 earned them a spot on the One Tree Hill Road Mix compilation. -

The Barns at Wolf Trap Welcomes International Guitar Night; Ari Hest

January 9, 2014 Contact: Camille Cintrón, Manager, Public Relations 703.255.4096 or [email protected] The Barns at Wolf Trap Welcomes International Guitar Night; Ari Hest with Special Guest Sarah Siskind; Sonny Landreth and Cindy Cashdollar; Paul Cebar Tomorrow Sound; and Maceo Parker All Shows at The Barns at Wolf Trap 1635 Trap Road, Vienna, VA 22182 International Guitar Night Featuring: Brian Gore, Italy’s Pino Forastiere, Mike Dawes from England, and Quique Sinesi from Argentina Thursday, January 16, 2014 at 8 pm Friday, January 17, 2014 at 8 pm $25-$27 Showcasing extraordinary songwriting and playing skills which demonstrate a high level of both technical ability and musicality, International Guitar Night has become a major force in live contemporary guitar music. This year’s version of North America’s premier touring guitar festival features guitarists from South America, Italy, England, and the United States. American “guitar poet” Brian Gore’s playing contains a “bounce and spaciousness all his own” (Los Angeles Times). He created International Guitar Night in 1995 and has released multiple albums and books on fingerstyle guitar. Italian steel-string guitarist Pino Forastiere fuses the classical, contemporary, and rock genres as he “employs a dazzling blend of slapping, tapping, strumming, altered tunings, and harmonics, combined with classical phrasing and a focus on distinct and addictive melodies” (Guitar Player). English fingerstyle guitarist Mike Dawes has developed a multifaceted repertoire of sound in his short but successful career, fusing Celtic, rock, jazz, and experimental music to create a product all his own. He has gained praise from artists like Gotye, Frank Turner, and Justin Hayward. -

3N1 Final.Pdf

cvr1 FSG bw page cvr2 The official journal of the Young Adult Library Services Association VOLUME 3 NUMBER 1 FALL 2004 ISSN 1541-4302 CONTENTS FROM THE EDITOR 2 ARTICLES FROM THE PRESIDENT 35 Publishing 101: A Guide 3 What YALSA Means to Me for the Perplexed David Mowery Publishers Offer Insight through Orlando Program and Interviews ARTICLES Roxy Ekstrom and Amy Alessio 6 Ten Years and Counting 37 YA Galley Project Gives Teens YALSA’s Serving the Underserved a New Voice Project, 1994–2004 Diane Monnier and Francisca Monique le Conge Goldsmith 13 What Does Professionalism Mean 40 Young Adults as Public for Young Adult Librarians? Library Users Dawn Rutherford A Challenge and Priority 16 Reaching Out to Young Adults Ivanka Stricevic in Jail 42 An Unscientific Study of Teen Patrick Jones TV Programming 20 Making a Difference Leslie Marlo Incarcerated Teens Speak Diana Tixier Herald THE UPDATE 44 AWARD SPEECHES 22 Margaret A. Edwards Lifetime GUIDELINES FOR Achievement Award Speech AUTHORS Ursula K. Le Guin 15 26 Michael L. Printz Award Speech INDEX TO ADVERTISERS Angela Johnson 50 28 Michael L. Printz Honor Speech K. L. Going 29 Michael L. Printz Honor Speech Helen Frost 30 Michael L. Printz Honor Speech Carolyn Mackler 33 Michael L. Printz Honor Speech Jennifer Donnelly FROM THE EDITOR amed tennis player Arthur Ashe once said, “From what we get, we can make a living; what we give, YALSA Publications Committee (performing referee duties and providing advisory input for the journal) however, makes a life.” His causes Donald Kenney, Chair, Blacksburg, Virginia were many, and he shared his Lauren Adams, Newton, Massachusetts Sophie R. -

Route N10 - City to Otara Via Manukau Rd, Onehunga, Mangere and Papatoetoe

ROUTE N10 - CITY TO OTARA VIA MANUKAU RD, ONEHUNGA, MANGERE AND PAPATOETOE Britomart t S Mission F t an t r t sh e S e S Bay St Marys aw Qua College lb n A y S e t A n Vector Okahu Bay St Heliers Vi e z ct t a o u T r S c Arena a Kelly ia Kohimarama Bay s m A S Q Tarltons W t e ak T v a e c i m ll e a Dr Beach es n ki le i D y S Albert r r t P M Park R Mission Bay i d a Auckland t Dr St Heliers d y D S aki r Tama ki o University y m e e Ta l r l l R a n Parnell l r a d D AUT t S t t S S s Myers n d P Ngap e n a ip Park e r i o Auckland Kohimarama n R u m e y d Domain d Q l hape R S R l ga d an R Kar n to d f a N10 r Auckland Hobson Bay G Hospital Orakei P Rid a d de rk Auckland ll R R R d d Museum l d l Kepa Rd R Glendowie e Orakei y College Grafton rn Selwyn a K a B 16 hyb P College rs Glendowie Eden er ie Pass d l Rd Grafton e R d e Terrace r R H Sho t i S d Baradene e R k h K College a Meadowbank rt hyb r No er P Newmarket O Orakei ew ass R Sacred N d We Heart Mt Eden Basin s t Newmarket T College y a Auckland a m w a ki Rd Grammar d a d Mercy o Meadowbank R r s Hospital B St Johns n Theological h o St John College J s R t R d S em Remuera Va u Glen ll d e ey G ra R R d r R Innes e d d St Johns u a Tamaki R a t 1 i College k S o e e u V u k a v lle n th A a ra y R R d s O ra M d e Rd e u Glen Innes i em l R l i Remuera G Pt England Mt Eden UOA Mt St John L College of a Auckland Education d t University s i e d Ak Normal Int Ea Tamaki s R Kohia School e Epsom M Campus S an n L o e i u n l t e e d h re Ascot Ba E e s Way l St Cuthberts -

Village of Hall and District Progress Association Inc. Annual Report

Village of Hall and District Progress Association Inc. Annual Report 2009 – 2010 INTRODUCTION Committee members are asked from time to time ‘what does the Progress Association do?’ Our Annual Reports seek to answer this question. In short, we have managed the Hall and district website (hall.act.au) and the Rural Fringe, partnered with government in planning and developing around a million dollars worth of community facilities, won and managed two government projects – one ACT and one Commonwealth – each worth around $10,000, initiated a Men’s Shed, made significant gains in recognition, conservation and interpretation of Hall and district heritage, staged a very popular twilight Concert by the Hall Village Brass Band, supported the National Sheep Dog Trials, and taken on the organization of the Hall School Centenary in 2011. Endeavours such as these are in addition to the on-going task of maintaining relationships with local MLA’s and representing the interests of the Hall and district community to the ACT government on a whole range of matters. MEMBERS As well as maintaining the Rural Fringe and the community website as community services, we circulate periodic email updates to members on forthcoming events, and important issues. We also respond to a steady stream of requests for information. Lacking a reliable source of surplus income, the Association is not a funding body as such. We nevertheless made contributions to the community dinner during the Sheep Dog Trials (paying for the Band) , and a special grant to the Hall Village Brass Band to enable them to acquire uniforms. The Band is one of our many valued affiliated organizations. -

The History of Gender Representations in Teen Television

The History of Gender Representations in Teen Television Author: Nicole Sandonato Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/3869 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2014 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. The History of Gender Representations in Teen Television By Nicole Sandonato A Senior Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of Communication Boston College May 2014 The History of Gender Representations in Teen Television Sandonato i Acknowledgements First, I wish to thank Professor William Stanwood for his endless help on this thesis. This paper would not have been possible without his guidance and editing skills. Thank you for calming my nerves and making me believe in myself and my ability to write this paper. I am a more confident writer, student and person because of your help. Thank you! I wish to thank my roommate Megan Cannavina for her constant support during this whole process. Through every stress, deadline, and revision, she was there to hold me together and reminded me that “I got this”. You help me to stop doubting myself and to reach for the stars! I would also like to thank my family for their love, support and encouragement in all my academic endeavors. I am so blessed to have you all behind me for every step in my journey. I love and thank you! The History of Gender Representations in Teen Television Sandonato ii Table of Contents Acknowledgments ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Kelly Valentine Hendry

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Kelly Valentine Hendry Talent Representation Telephone Madeleine Dewhirst & Sian +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 Smyth Address [email protected] Hamilton Hodell, 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Television Title Director Producer Production Company Amblin/Dreamworks for NBC BRAVE NEW WORLD Owen Harris David Wiener Universal GANGS OF LONDON Gareth Evans Sister Pictures/Pulse Films HBO/Sky Atlantic CITADEL Brian Kirk Sarah Bradshaw AGBO/Amazon Sony Pictures THE WHEEL OF TIME Uta Briesewitz Rafe Judkins Television/Amazon Studios Emma Kingsman- DEADWATER FELL Lynsey Miller Kudos/Channel 4 Lloyd/Diederick Santer COBRA Hans Herbots Joe Donaldson New Pictures for Sky One UNTITLED BRIDGERTON PROJECT Julie Anne Robinson Shondaland Netflix GHOSTS Tom Kingsley Matthew Mulot Monumental Pictures/BBC GOLD DIGGER Vanessa Caswill Mainstreet Pictures BBC1 THE SPY Gideon Raff Legend Films Netflix Brian Kaczynski/Stuart THE CRY Glendyn Ivin Synchronicity Films/BBC1 Menzies Naomi De Pear/Katie THE BISEXUAL Desiree Akhavan Sister Pictures for Hulu and C4 Carpenter HARLOTS Coky Giedroyc Grainne Marmion Monumental Pictures for Hulu Fuqua Films/Entertainment ICE Various Robert Munic One Vertigo Films/Company BULLETPROOF! Nick Love Jon Finn Pictures Robert Connolly/Matthew Hilary Bevan Jones/Tom DEEP STATE Endor/Fox Parkhill Nash BANCROFT John Hayes Phil Collinson Tall Story Pictures/ITV Catherine Oldfield/Francis TRAUMA Marc Evans Tall Story Pictures/ITV Hopkinson/Mike Bartlett RIVIERA Philipp Kadelbach/Various Foz Allen -

Killer Movie (2008), Heber Holiday (2007) and Evidence (2013), Starring Stephen Moyer

‘WRITE BEFORE CHRISTMAS’ Cast Bios TORREY DEVITTO (Jessica) – Widely known for her leading role in the current NBC drama “Chicago Med,” Torrey DeVitto is a renowned actress, model and musician. “Chicago Med” hails from the same creators of “Chicago Fire” and “Chicago PD” the latest spin-off focusing on the day-to-day chaos of the team of doctors running the ER. DeVitto plays Natalie Manning, a doctor in the ER Pediatrics division. The show has become the most watched program on Wednesday nights from viewers 18-49 and the series is currently in its fifth season. In 2013, DeVitto was seen as the gorgeous Maggie Hall in the final season of Lifetime’s popular drama, “Army Wives.” She is best known for her stellar recurring roles as Melissa Hastings in the ABC Family/Freeform series “Pretty Little Liars” from 2010 to 2017, Dr. Meredith Fell in The CW fantasy drama “The Vampire Diaries” from 2012 to 2013 and as Carrie in The CW drama “One Tree Hill” from 2008 to 2009 Other notable work includes her roles as Alexandra on the MTV pilot, “Alexandra the Great,” guest-starring on the FBC pilot, “One Big Happy,” guest-starring in “The Untitled Michael Jacobs Pilot” for FBC, and guest-starring on episodes of “Scrubs” (2001), “Dawson's Creek” (1998), “Jack & Bobby (2004), “The King of Queens,” (1998), “ Drake & Josh” (2004), “CSI: Miami” (2002) and “Castle” (2009). DeVitto booked her first lead on the ABC Family series, “Beautiful People” (2005) as aspiring model Karen Kerr. Her film debut was in Starcrossed (2005), and she has appeared in the 2006 movie sequel, I'll Always Know What You Did Last Summer (2006), The Rite (2011) with Anthony Hopkins, Green Flash (2008), Killer Movie (2008), Heber Holiday (2007) and Evidence (2013), starring Stephen Moyer.