Sri Lanka, Presidential Election, 16 November 2019: EU EOM Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRITICAL THEORY and AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism

CDSMS EDITED BY JEREMIAH MORELOCK CRITICAL THEORY AND AUTHORITARIAN POPULISM Critical Theory and Authoritarian Populism edited by Jeremiah Morelock Critical, Digital and Social Media Studies Series Editor: Christian Fuchs The peer-reviewed book series edited by Christian Fuchs publishes books that critically study the role of the internet and digital and social media in society. Titles analyse how power structures, digital capitalism, ideology and social struggles shape and are shaped by digital and social media. They use and develop critical theory discussing the political relevance and implications of studied topics. The series is a theoretical forum for in- ternet and social media research for books using methods and theories that challenge digital positivism; it also seeks to explore digital media ethics grounded in critical social theories and philosophy. Editorial Board Thomas Allmer, Mark Andrejevic, Miriyam Aouragh, Charles Brown, Eran Fisher, Peter Goodwin, Jonathan Hardy, Kylie Jarrett, Anastasia Kavada, Maria Michalis, Stefania Milan, Vincent Mosco, Jack Qiu, Jernej Amon Prodnik, Marisol Sandoval, Se- bastian Sevignani, Pieter Verdegem Published Critical Theory of Communication: New Readings of Lukács, Adorno, Marcuse, Honneth and Habermas in the Age of the Internet Christian Fuchs https://doi.org/10.16997/book1 Knowledge in the Age of Digital Capitalism: An Introduction to Cognitive Materialism Mariano Zukerfeld https://doi.org/10.16997/book3 Politicizing Digital Space: Theory, the Internet, and Renewing Democracy Trevor Garrison Smith https://doi.org/10.16997/book5 Capital, State, Empire: The New American Way of Digital Warfare Scott Timcke https://doi.org/10.16997/book6 The Spectacle 2.0: Reading Debord in the Context of Digital Capitalism Edited by Marco Briziarelli and Emiliana Armano https://doi.org/10.16997/book11 The Big Data Agenda: Data Ethics and Critical Data Studies Annika Richterich https://doi.org/10.16997/book14 Social Capital Online: Alienation and Accumulation Kane X. -

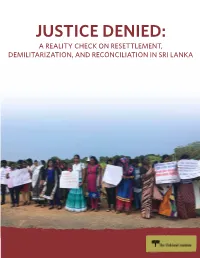

Justice Denied: a Reality Check on Resettlement, Demilitarization, And

JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA Acknowledgements This report was written by Elizabeth Fraser with Frédéric Mousseau and Anuradha Mittal. The views and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of The Oakland Institute alone and do not reflect opinions of the individuals and organizations that have sponsored and supported the work. Cover photo: Inter-Faith Women’s Group in solidarity protest with Pilavu residents, February 2017 © Tamil Guardian Design: Amymade Graphic Design Publisher: The Oakland Institute is an independent policy think tank bringing fresh ideas and bold action to the most pressing social, economic, and environmental issues. Copyright © 2017 by The Oakland Institute. This text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such uses be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, reuse in other publications, or translation or adaptation, permission must be secured. For more information: The Oakland Institute PO Box 18978 Oakland, CA 94619 USA www.oaklandinstitute.org [email protected] Acronyms CID Criminal Investigation Department CPA Centre for Policy Alternatives CTA Counter Terrorism Act CTF Consultation Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms IDP Internally Displaced Person ITJP International Truth and Justice Project LTTE Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam OMP Office on Missing Persons PTA Prevention of Terrorism Act UNCAT United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment UNHRC United Nations Human Rights Council 3 www.oaklandinstitute.org Executive Summary In January 2015, Sri Lanka elected a new President. -

Conversations with Stalin on Questions of Political Economy”

WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS Lee H. Hamilton, Conversations with Stalin on Christian Ostermann, Director Director Questions of Political Economy BOARD OF TRUSTEES: ADVISORY COMMITTEE: Joseph A. Cari, Jr., by Chairman William Taubman Steven Alan Bennett, Ethan Pollock (Amherst College) Vice Chairman Chairman Working Paper No. 33 PUBLIC MEMBERS Michael Beschloss The Secretary of State (Historian, Author) Colin Powell; The Librarian of Congress James H. Billington James H. Billington; (Librarian of Congress) The Archivist of the United States John W. Carlin; Warren I. Cohen The Chairman of the (University of Maryland- National Endowment Baltimore) for the Humanities Bruce Cole; The Secretary of the John Lewis Gaddis Smithsonian Institution (Yale University) Lawrence M. Small; The Secretary of Education James Hershberg Roderick R. Paige; (The George Washington The Secretary of Health University) & Human Services Tommy G. Thompson; Washington, D.C. Samuel F. Wells, Jr. PRIVATE MEMBERS (Woodrow Wilson Center) Carol Cartwright, July 2001 John H. Foster, Jean L. Hennessey, Sharon Wolchik Daniel L. Lamaute, (The George Washington Doris O. Mausui, University) Thomas R. Reedy, Nancy M. Zirkin COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES CHRISTIAN F. OSTERMANN, Series Editor This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Ninth Parliament - First Session) No. 62.] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Thursday, March 25, 2021 at 10.00 a.m. PRESENT : Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana, Speaker Hon. Angajan Ramanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Environment Hon. Dullas Alahapperuma, Minister of Power Hon. Mahindananda Aluthgamage, Minister of Agriculture Hon. Udaya Gammanpila, Minister of Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. (Dr.) Bandula Gunawardana, Minister of Trade Hon. Janaka Bandara Thennakoon, Minister of Public Services, Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Labour Hon. Vasudeva Nanayakkara, Minister of Water Supply Hon. (Dr.) Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Plantation Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Highways and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Tourism Hon. C. B. Rathnayake, Minister of Wildlife & Forest Conservation Hon. Chamal Rajapaksa, Minister of Irrigation and State Minister of National Security & Disaster Management and State Minister of Home Affairs Hon. Gamini Lokuge, Minister of Transport Hon. Wimal Weerawansa, Minister of Industries Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Weerasekera, Minister of Public Security Hon. M .U. M. Ali Sabry, Minister of Justice Hon. (Dr.) (Mrs.) Seetha Arambepola, State Minister of Skills Development, Vocational Education, Research and Innovation Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Co-operative Services, Marketing Development and Consumer Protection ( 2 ) M. No. 62 Hon. Ajith Nivard Cabraal, State Minister of Money & Capital Market and State Enterprise Reforms Hon. (Dr.) Nalaka Godahewa, State Minister of Urban Development, Coast Conservation, Waste Disposal and Community Cleanliness Hon. D. V. Chanaka, State Minister of Aviation and Export Zones Development Hon. Sisira Jayakody, State Minister of Indigenous Medicine Promotion, Rural and Ayurvedic Hospitals Development and Community Health Hon. -

Hansard (213-16)

213 වන කාණ්ඩය - 16 වන කලාපය 2012 ෙදසැම්බර් 08 වන ෙසනසුරාදා ெதாகுதி 213 - இல. 16 2012 சம்பர் 08, சனிக்கிழைம Volume 213 - No. 16 Saturday, 08th December, 2012 පාලෙනත වාද (හැනසා) பாராமன்ற விவாதங்கள் (ஹன்சாட்) PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) ල වාතාව அதிகார அறிக்ைக OFFICIAL REPORT (අෙශෝධිත පිටපත /பிைழ தித்தப்படாத /Uncorrected) අන්තර්ගත පධාන කරුණු නිෙව්දන : විෙශෂේ ෙවෙළඳ භාණ්ඩ බදු පනත : ෙපොදු රාජ මණ්ඩලීය පාර්ලිෙම්න්තු සංගමය, අන්තර් නියමය පාර්ලිෙම්න්තු සංගමය සහ “සාක්” පාර්ලිෙම්න්තු සංගමෙය් ඒකාබද්ධ වාර්ෂික මහා සභා රැස්වීම නිෂපාදන් බදු (විෙශෂේ විධිවිධාන) පනත : ශී ලංකා පජාතාන්තික සමාජවාදී ජනරජෙය් නිෙයෝගය ෙශෂේ ඨාධිකරණෙය්් අග විනිශචයකාර් ධුරෙයන් ගරු (ආචාර්ය) ශිරානි ඒ. බණ්ඩාරනායක මහත්මිය ඉවත් කිරීම සුරාබදු ආඥාපනත : සඳහා අතිගරු ජනාධිපතිවරයා ෙවත පාර්ලිෙම්න්තුෙව් නියමය ෙයෝජනා සම්මතයක් ඉදිරිපත් කිරීම පිණිස ආණ්ඩුකම වවසථාෙව්් 107(2) වවසථාව් පකාර ෙයෝජනාව පිළිබඳ විෙශෂේ කාරක සභාෙව් වාර්තාව ෙර්ගු ආඥාපනත : ෙයෝජනාව පශනවලට් වාචික පිළිතුරු වරාය හා ගුවන් ෙතොටුෙපොළ සංවර්ධන බදු පනත : ශී ලංකාෙව් පථම චන්දිකාව ගුවන්ගත කිරීම: නිෙයෝගය විදුලි සංෙද්ශ හා ෙතොරතුරු තාක්ෂණ අමාතතුමාෙග් පකාශය ශී ලංකා අපනයන සංවර්ධන පනත : විසර්ජන පනත් ෙකටුම්පත, 2013 - [විසිතුන්වන ෙවන් කළ නිෙයෝගය දිනය]: [ශීර්ෂ 102, 237-252, 280, 296, 323, 324 (මුදල් හා කමසම්පාදන);] - කාරක සභාෙව්දී සලකා බලන ලදී. -

Provisional Record 8 99Th Session, Geneva, 2010

International Labour Conference Provisional Record 8 99th Session, Geneva, 2010 Third sitting Thursday, 10 June 2010, 10.10 a.m. Presidents: Mr de Robien and Mr Nakajima support of more than 160 countries, the UN Eco- PRESENTATION OF THE REPORT OF THE CHAIRPERSON nomic and Social Council adopted the resolution, OF THE GOVERNING BODY “Recovering from the crisis: A Global Jobs Pact”. If employment and social protection were to be the Original French: The PRESIDENT (Mr DE ROBIEN) drivers and ultimate purposes of the recovery, the We will begin our work with the presentation of Pact had to be streamlined into the multilateral sys- the report of the Chairperson of the Governing tem. What was born as a portfolio of concrete Body to the Conference for the year 2009–10. The measures had to become an international reference. report is published in Provisional Record No. 1. It had to be an inspiration to a more sustainable I now give the floor to Ms Farani Azevêdo, economy and a more democratic and legitimate in- Chairperson of the Governing Body. After her pres- ternational order. As was stated last November by entation, I will give the floor to the spokespersons Minister Celso Amorim of Brazil in the Working of the groups and open the general discussion. Party on the Social Dimension of Globalization, a Ms AZEVÊDO (Chairperson of the Governing Body of the new and more inclusive global governance is re- International Labour Office) quired to protect the most vulnerable members of I would like first to recall that tomorrow is the society. -

Cal WRIT/ 89/2015 Vs

1 IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA In the matter of an Application for order in the nature of Writ of Quo Warrantor, certiorari and Mandamus under and in terms of Article 140 of the Constitution. General Sarath Fonseka of No.461/7, Pubudu Pedesa, I Wali Road, i Thalawathugoda. \'.1 PETITIONER CAl WRIT/ 89/2015 Vs, 1. Dhammika Kitulgoda, Former Secretary- General of Parliament, Parliament of Sri Lanka, Sri Jayewardenepura, Kotte. 2. Da yananda Dissana yake, Former Commissioner of Elections, 83/C Honnantara South, Samupakara Mw, Piliyandala. 3. Dhammika Dasanayake, Secretary- General Parliament, Parliament of Sri Lanka, Sri Jayewardenepura, Kotte. 4. Mahinda Deshapriya, Commissioner of Elections, Elections Secretariat, \ 2 Rajagiriya. 5. H.K. Kamal Padmasiri, Returning Officer, District Secretariat, Colombo 05. 6. Lakshman Nipunarachchi of No.07 Rajaye Niwasa, Bokundara, Piliyandala. 7. Jayantha Ketagoda of No.12/A, Dambugahawatta, Malabe. 8. Hon. Attorney General, Attorney General's Department, Colombo 12. RESPONDENTS f f Before : Vijith K. Malalgoda PC J (PICA) & J '\, H.C.J. Madawala J Counsel : Faiz Musthapha PC with Upul Jayasuriya, S.P. Sriskantha and Ifthikar Asihq for the Petitioner, Ms. Farzana Jameel Senior DSG with Sumith Dharmawardhane DSG and rd th th th Yuresha de. Silva for the 3 ,4 , 5 and 8 Respondents, Srinath Perera PC with Buddhika Wansharatne for the i h Respondent 3 Argued On : 13.05.2015 Written Submissions On : 29.05.2015, 03.06.2015 Order On : 18.06.2015 Order Vijith K. Malalgoda PC J (PICA) The Petitioner has filed the present Application before this Court seeking inter alia; b). -

In the Supreme Court of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA In the matter of an Application under and in terms of Articles 17 and 126 of the Constitution of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka 1. Centre for Policy Alternatives (Guarantee) Ltd., No.24/2 28 th Lane, Off Flower Road, Colombo 7. 2. Dr. Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu No. 03, Ascot Avenue, Colombo 5. Petitioners SC (FR) Application No. vs. 1. D. M. Jayaratne, Prime Minister, Prime Minister’s Office, 58, Sir Ernest De Silva Mawatha, Colombo 7 2. Chamal Rajapakse, Speaker of Parliament, Parliament of Sri Lanka, Sri Jayewardenepura Kotte 3. Ranil Wickremasinghe, Leader of the Opposition, 115, 5 th Lane, Colombo 3 4. A H M Azwer, Member of Parliament, 4, Bhatiya Road, Dehiwala 5. D M Swaminathan, Member of Parliament, 125, Rosmead Place, Colombo 07 6. Mohan Pieris, President’s Counsel, 3/144, Kynsey Road, Colombo 8 7. The Attorney General, Attorney General’s Department, Hulftsdorp, Colombo 12 Respondents 1/19 On this 15th day of January 2013 TO: THE HONOURABLE CHIEF JUSTICE AND THEIR LORDSHIPS THE OTHER HONOURABLE JUDGES OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA The Petition of the Petitioners above named appearing by Namal Rajapaksha their Registered Attorney-at-Law states as follows: THE PETITIONERS 1. The 1 st Petitioner is a body incorporated under the laws of Sri Lanka (and duly re- registered in terms of the Companies Act No.7 of 2007) and is made up of members, more than three-fourths of whom are citizens of Sri Lanka. -

Reforming Sri Lankan Presidentialism: Provenance, Problems and Prospects Volume 2

Reforming Sri Lankan Presidentialism: Provenance, Problems and Prospects Edited by Asanga Welikala Volume 2 18 Failure of Quasi-Gaullist Presidentialism in Sri Lanka Suri Ratnapala Constitutional Choices Sri Lanka’s Constitution combines a presidential system selectively borrowed from the Gaullist Constitution of France with a system of proportional representation in Parliament. The scheme of proportional representation replaced the ‘first past the post’ elections of the independence constitution and of the first republican constitution of 1972. It is strongly favoured by minority parties and several minor parties that owe their very existence to proportional representation. The elective executive presidency, at least initially, enjoyed substantial minority support as the president is directly elected by a national electorate, making it hard for a candidate to win without minority support. (Sri Lanka’s ethnic minorities constitute about 25 per cent of the population.) However, there is a growing national consensus that the quasi-Gaullist experiment has failed. All major political parties have called for its replacement while in opposition although in government, they are invariably seduced to silence by the fruits of office. Assuming that there is political will and ability to change the system, what alternative model should the nation embrace? Constitutions of nations in the modern era tend fall into four categories. 1.! Various forms of authoritarian government. These include absolute monarchies (emirates and sultanates of the Islamic world), personal dictatorships, oligarchies, theocracies (Iran) and single party rule (remaining real or nominal communist states). 2.! Parliamentary government based on the Westminster system with a largely ceremonial constitutional monarch or president. Most Western European countries, India, Japan, Israel and many former British colonies have this model with local variations. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Eighth Parliament - First Session) No. 134. ] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Tuesday, December 06, 2016 at 9.30 a. m. PRESENT : Hon. Karu Jayasuriya, Speaker Hon. Thilanga Sumathipala, Deputy Speaker and Chairman of Committees Hon. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister and Minister of National Policies and Economic Affairs Hon. (Mrs.) Thalatha Atukorale, Minister of Foreign Employment Hon. Wajira Abeywardana, Minister of Home Affairs Hon. John Amaratunga, Minister of Tourism Development and Christian Religious Affairs and Minister of Lands Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Development Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Amunugama, Minister of Special Assignment Hon. Gayantha Karunatileka, Minister of Parliamentary Reforms and Mass Media and Chief Government Whip Hon. Ravi Karunanayake, Minister of Finance Hon. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam, Minister of Education Hon. Lakshman Kiriella, Minister of Higher Education and Highways and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. Mano Ganesan, Minister of National Co-existence, Dialogue and Official Languages Hon. Daya Gamage, Minister of Primary Industries Hon. Dayasiri Jayasekara, Minister of Sports Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation Hon. Palany Thigambaram, Minister of Hill Country New Villages, Infrastructure and Community Development Hon. Duminda Dissanayake, Minister of Agriculture Hon. Navin Dissanayake, Minister of Plantation Industries Hon. S. B. Dissanayake, Minister of Social Empowerment and Welfare ( 2 ) M. No. 134 Hon. S. B. Nawinne, Minister of Internal Affairs, Wayamba Development and Cultural Affairs Hon. Gamini Jayawickrama Perera, Minister of Sustainable Development and Wildlife Hon. Harin Fernando, Minister of Telecommunication and Digital Infrastructure Hon. A. D. Susil Premajayantha, Minister of Science, Technology and Research Hon. Sajith Premadasa, Minister of Housing and Construction Hon. -

PE 2020 MR 82 S.Pdf

Election Commission – Sri Lanka Parliamentary Election - 05.08.2020 Registered electronic media to disseminate certified election results Last Updated Online Social Media No Organization TV FM Publishers(News Other News Websites (FB/ SMS Paper Web Sites) YouTube/ Twitter) 1 Telshan Network TNL TV - - - - - (Pvt) Ltd 2 Smart Network - - - www.lankasri.lk - - (Pvt) Ltd 3 Bhasha Lanka (Pvt) - - - www.helakuru.lk - - Ltd 4 Digital Content - - - www.citizen.lk - - (Pvt) Ltd 5 Ceylon News - - www.mawbima.lk, - - - Papers (Pvt) Ltd www.ceylontoday.lk Independent ITN, Lakhanda, www.itntv.lk, ITN Sri Lanka 6 Television Network Vasantham TV Vasantham - www.itnnews.lk (FB) - Ltd FM Lakhanda Radio (FB) Sri Lanka City FM 7 Broadcasting - - - - - Corporation (SLBC) Asia Broadcasting Hiru FM. 8 Corparation Hiru TV Shaa FM, www.hirunews.lk, Sooriyan FM, - www.hirugossip.lk - - Sun FM, Gold FM 9 Asset Radio Broadcasting (Pvt) - Neth FM - www.nethnews.lk NethFM(FB) - Ltd 1/4 File Online Number Organization TV FM Publishers(News Other News Websites Social Media SMS Paper Web Sites) Asian Media 10 Publications (Pvt) ltd - - www.thinakkural.lk - - - 11 EAP Broadcasting Swarnavahini Shree FM, - www.swarnavahini.lk, - - Company Ran FM www.athavannews.com 12 Voice of Asia Siyatha TV Siyatha FM - - - - Network (Pvt)Ltd Star tamil TV MTV Channel (Pvt) Sirasa TV, Sirasa FM, News 1st (FB), News 1st SMS 13 Ltd / MBC Shakthi TV, Shakthi FM, News 1st (S,T,E), Networks (Pvt) Ltd TV1 Yes FM, - www.newsfirst.lk (Youtube), KIKI mobile YFM, News 1st App Legends FM (Twitter) -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Eighth Parliament - First Session) No. 187. ] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Wednesday, August 09, 2017 at 1.00 p. m. PRESENT : Hon. Karu Jayasuriya, Speaker Hon. Thilanga Sumathipala, Deputy Speaker and Chairman of Committees Hon. Selvam Adaikkalanathan, Deputy Chairman of Committees Hon. Ranil Wickremesinghe, Prime Minister and Minister of National Policies and Economic Affairs Hon. (Mrs.) Thalatha Atukorale, Minister of Foreign Employment Hon. John Amaratunga, Minister of Tourism Development and Christian Religious Affairs Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Development and State Minister of Mahaweli Development Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Amunugama, Minister of Special Assignment Hon. Gayantha Karunatileka, Minister of Lands and Parliamentary Reforms and the Chief Government Whip Hon. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam, Minister of Education Hon. Lakshman Kiriella, Minister of Higher Education and Highways and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. Dayasiri Jayasekara, Minister of Sports Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Transport and Civil Aviation Hon. Duminda Dissanayake, Minister of Agriculture Hon. S. B. Dissanayake, Minister of Social Empowerment, Welfare and Kandyan Heritage Hon. S. B. Nawinne, Minister of Internal Affairs, Wayamba Development and Cultural Affairs Hon. Gamini Jayawickrama Perera, Minister of Sustainable Development and Wildlife Hon. A. D. Susil Premajayantha, Minister of Science, Technology and Research ( 2 ) M. No. 187 Hon. Sajith Premadasa, Minister of Housing and Construction Hon. (Mrs.) Chandrani Bandara, Minister of Women and Child Affairs Hon. Tilak Marapana, Minister of Development Assignments Hon. Faiszer Musthapha, Minister of Provincial Councils and Local Government Hon. Anura Priyadharshana Yapa, Minister of Disaster Management Hon. Sagala Ratnayaka, Minister of Law and Order and Southern Development Hon.