The Effect of Emotions Among Different Sports During Competition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 07 P.1.Qxp

THE GREEK AUSTRALIAN The oldest circulating Greek newspaper outside Greece email: VEMA [email protected] JANUARY 2007 Tel. (02) 9559 7022 Fax: (02) 9559 7033 In this issue... Our Primate’s View WHEN ‘PLUSES’ BECOME ‘MINUSES’ (Professor Joseph Ratzinger, as Pope Benedict XVI) PAGES 5/23 - 6/24 Housing affordability FEATURE The ageless spirit of Hellenism at record low PAGE 19/37 Dreams of buying a home are even fur- ther out of reach for many first-time buy- ers because of rising interest rates and higher prices, Australia's peak building body says. Last year's three interest rate rises, coupled with an ongoing shortage of housing stock, has sent affordability to a record low, the Housing Industry Association (HIA) said. And for the first time in history, Perth hous- ing for first-time buyers is now less afford- able than Sydney. HIA is calling on federal and state govern- ments to take action over the housing crisis. Releasing its quarterly Housing Affordabi- lity Index, HIA's executive director of hous- ing and economics, Simon Tennent, said it had become patently obvious that the cor- rection in housing markets and improve- Greece in row with ment in affordability predicted two years ago was way off the mark. FYROM over "The combination of rising prices over the monwealth Bank Housing Affordability home buyer income, up 1.7 percentage quarter and the triple whammy of higher Index for first-time buyers fell 5.5 per cent, points on the September quarter. Alexander the Great interest rates has pushed housing out of its fourth consecutive decline, and was 15.5 The median first-home price, based on reach for an increasing number of house- per cent lower than a year earlier. -

MIS Code: 5016090

“Developing Identity ON Yield, SOil and Site” “DIONYSOS” MIS Code: 5016090 Deliverable: 3.1.1 “Recording wine varieties & micro regions of production” The Project is co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund and by national funds of the countries participating in the Interreg V-A “Greece-Bulgaria 2014-2020” Cooperation Programme. 1 The Project is co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund and by national funds of the countries participating in the Interreg V-A “Greece-Bulgaria 2014-2020” Cooperation Programme. 2 Contents CHAPTER 1. Historical facts for wine in Macedonia and Thrace ............................................................5 1.1 Wine from antiquity until the present day in Macedonia and Thrace – God Dionysus..................... 5 1.2 The Famous Wines of Antiquity in Eastern Macedonia and Thrace ..................................................... 7 1.2.1 Ismaric or Maronite Wine ............................................................................................................ 7 1.2.2 Thassian Wine .............................................................................................................................. 9 1.2.3 Vivlian Wine ............................................................................................................................... 13 1.3 Wine in the period of Byzantium and the Ottoman domination ....................................................... 15 1.4 Wine in modern times ......................................................................................................................... -

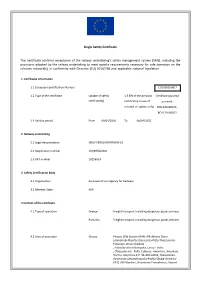

Single Safety Certificate.Pdf

Single Safety Certificate This certificate confirms acceptance of the railway undertaking's safety management system (SMS), including the provisions adopted by the railway undertaking to meet specific requirements necessary for safe operation on the relevant network(s), in conformity with Directive (EU) 2016/798 and applicable national legislation. 1. Cerfiticate Information 1.1 European Identification Number EU1020200017 1.2 Type of the certificate Update of safety 1.3 EIN of the previous Certificat siguranta certificate(s) certificate (in case of partea B: renewal or update only) RO1220190127, RO1120180022 1.4 Validity period From 09/04/2020 To 08/04/2025 2. Railway undertaking 2.1 Legal denomination GRUP FEROVIAR ROMAN SA 2.2 Registration number J40/8958/2001 2.3 VAT number 14256514 3. Safety Certification Body 3.1 Organisation European Union Agency for Railways 3.2 Member State N/A 4.Content of the certificate 4.1 Type of operation Greece Freight transport, Including dangerous goods services Romania Freight transport, Including dangerous goods services 4.2 Area of operation Greece Piraeus (Old Station SPAP)-AIR-Athens-Oinoi- Leianokladi-Plaiofarsalos-Larisa-Platy-Thessaloniki- Eidomeni, Oinoi-Chalkida , Palaiofarsalos-Kalampaka, Larisa - Volos , (Thessaloniki) - Palty- Eddessa- Amyntaio, Amyntaio - Florina, Amyntaio-K.P. 32+500 AmKZ, Thessaloniki- Strymonas-Alexandroupolis-Pythio-Dikaia-Ormenio- KP32+900 Borders, Strymonas-Promahonas, Airport (El. Venizelos)-Metamorfosi-SKA-Liosia-Korinthos- Kiato, Neo Ikonio-KP 25+286, Athens-Liosia, Athens- Metamorfosi Romania Intreaga retea feroviara din România / the whole railway network from Romania 4.3 Operations to border stations Greece Romania Hungary Lokoshaza Kotegyan Biharkeresztes Nirabrany Agerdomajor Bulgaria Ruse Kardam Vidin Tovarna 4.4 Restrictions and conditions of use Greece Romania 4.5 Applicable national legislation Greece Law 4632/2019, Government Gazette no 159 of 14 October 2019 Romania Legal framework applicable for the Romanian railway sector 4.6 Additional information Greece Romania 5. -

Commission Implementing Decision 2014/709/EU Lays Down Animal Health Control Measures in Relation to African Swine Fever in Certain Member States

COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING DECISION of 9 October 2014 concerning animal health control measures relating to African swine fever in certain Member States and repealing Implementing Decision 2014/178/EU (notified under document C(2014) 7222) (Text with EEA relevance) 2014/709/EU (OJ No. L 295, 11.10.2014, p. 63) amended by (EU) 2015/251 (OJ No. L 41, 17.02.2015, p. 46) amended by (EU) 2015/558 (OJ No. L 92, 08.04.2015, p. 109) amended by (EU) 2015/820 (OJ No. L 129, 27.05.2015, p. 41) amended by (EU) 2015/1169 (OJ No. L 188, 16.07.2015, p. 45) amended by (EU) 2015/1318 (OJ No. L 203, 31.07.2015, p. 14) amended by (EU) 2015/1372 (OJ No. L 211, 08.08.2015, p. 34) amended by (EU) 2015/1405 (OJ No. L 218, 19.08.2015, p. 16) amended by (EU) 2015/1432 (OJ No. L 224, 27.08.2015, p. 39) amended by (EU) 2015/1783 (OJ No. L 259, 06.10.2015, p. 27) amended by (EU) 2015/2433 (OJ No. L 334, 22.12.2015, p. 46) amended by (EU) 2016/180 (OJ No. L 35, 11.02.2016, p. 12) amended by (EU) 2016/464 (OJ No. L 80, 31.03.2016, p. 36) amended by (EU) 2016/857 (OJ No. L 142, 31.05.2016, p. 14) amended by (EU) 2016/1236 (OJ No. L 202, 28.07.2016, p. 45) amended by (EU) 2016/1372 (OJ No. L 217, 12.08.2016, p. 38) amended by (EU) 2016/1405 (OJ L 228, 23.08. -

Results Factsheet Indicator Set06: Accessibility of Transport Modes

RESULTS FACTSHEET May 2011 INDICATOR SET06: ACCESSIBILITY OF TRANSPORT MODES RESULTS FACTSHEET INDICATOR SET06: ACCESSIBILITY OF TRANSPORT MODES DEFINITION - OBJECTIVE This indicator records data on the airports, railway stations and ports located in the Regions of the Egnatia Motorway Impact Zones, and more specifically: (a) their location, (b) their position in an official rating according to their significance, (c) the volume of passenger and commercial traffic they serve, and (d) their distance and time distance from the closest Egnatia Motorway junction. The indicator monitors the impact of the Egnatia Motorway on the accessibility of other types of transport modes. The optimum connection between the motorway and other transport modes constitutes a basic parameter in developing an integrated system of combined transport. RESULTS – ASSESSMENT The results presented in this factsheet mainly derive from the “Study on the accessibility indicators of special interest areas and public transport in the zone of the regions crossed by the Egnatia Motorway”, which was conducted for the Observatory of “EGNATIA ODOS A.E.” in 2009. This study recorded 44 public transportation infrastructure locations in the Egnatia Motorway Impact Zone IV1, out of which 26 are railway stations, while 9 are ports and 9 are airports. 14 infrastructures are located in the Region of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace, 12 in the Region of Central Macedonia, 8 in the Region of Thessaly and 5 in the Regions of Western Macedonia and Epirus. The distance and time distance of each public transport infrastructure location from the closest Egnatia Motorway IC is presented per Region in the following tables. 1 Impact Zone IV concerns the motorway impacts in the Zone of the Regions crossed by the Egnatia Motorway, i.e. -

Eastern Macedonia and Thrace : Quick Facts (I)

Region of Eastern Macedonia-Thrace Investment Profile November 2017 Contents 1. Profile of the Region of Eastern Macedonia-Thrace 2. Eastern Macedonia-Thrace’ competitive advantages 3. Investment Opportunities 1. Profile of the Region of Eastern Macedonia-Thrace 2. Eastern Macedonia-Thrace’ competitive advantages 3. Investment Opportunities 4. Investment Incentives The Region of Eastern Macedonia and Thrace : Quick facts (I) Eastern Macedonia and Thrace consists of the northeastern parts of the country, and is divided into the Macedonian regional units of Drama, Kavala and Thasos and the Thracian regional units of Xanthi, Rhodope, Evros and Samothrace •The Region covers 14.157 sq. km corresponding to 10,7% of the total area of Greece. It borders Bulgaria and Turkey to the north, the prefecture of Serres to the west and the Thracian Sea to the south •The Prefecture of Evros, the borderline of Greece is the largest prefecture of Thrace. It borders Bulgaria to the north and northeast and Turkey to the East, having the river Evros, The island of Samothrace also belongs to the prefecture of Evros •The prefecture of Rhodope lies in central Thrace covering 2,543 sq. km. The capital of the prefecture is Komotini, the administrative seat of the Region of East Macedonia and Thrace. •The prefecture 4.of Xanthi Investment covers 1,793 sq .Incentives km., of which 27% is arable land, 63% forests and 3% meadows in the plains •The Prefecture of Kavala is in East Macedonia and covers 2,110 sq. km. The islands of Thassos and Thassopoula also belong to the prefecture •The prefecture of Drama is well-known for the verdant mountain ranges, the water springs, the rare flora and fauna. -

Pilot Project a Study of Cargo Flows & the Logistics Demand for a Freight

PILOT PROJECT A STUDY OF CARGO FLOWS & THE LOGISTICS DEMAND FOR A FREIGHT CENTRE IN THESPROTIA GREEK PROJECT TEAM LEADER OF THE GREEK TEAM PREFECTURE OF THESPROTIA CHAMBER OF COMMERCE OF THESPROTIA SUB-CONTRACTORS IMPETUS ENGINEERING S.A. 3-5 DIMITSANIS STR., 183 46 MOSCHATO TEL.: +30 210 4838938 FAX: +30 210 4836807 e-mail: [email protected] Dec. 2005 I-LOG - PILOT PROJECT A IN THESPROTIA STUDY OF CARGO FLOWS AND THE LOGISTICS DEMAND FOR A FREIGHT CENTRE IN THESPROTIA Table of Contents 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1. The necessity of creating a freight centre in Thesprotia ......................................................................... 3 1.2. Development of Container Traffic in the Mediterranean Markets ............................................................. 3 1.2.1. General development considerations ............................................................................................. 3 1.2.2. Structure of shipping within the Mediterranean .............................................................................. 4 1.2.3. Forecast of container shipping in the Mediterranean Sea................................................................. 6 1.2.4. Trade Flows ................................................................................................................................. 8 1.2.5. Commodity specific analysis ....................................................................................................... -

Download (PDF, 539.19

GREECE Reference map as of 11 Jun 2018 Svilengrad / Ormenio D Karaagac / Kastanies BULGARIA Haskovo / Trigono Û D THE FORMER D E" Orestiada Fylakio - RIC Ivayalovgrad Evros-Orestiada Black Sea Û YUGOSLAV REPUBLIC D E" Diavata Kulata / Promachonas Tirana OF MACEDONIA Û GREECE Idomeni / Gevgelija Û E" Thessaloniki Port Û D Drama D D# Û Serres (KEGE) E" Uzunkopru / Pythio E" Û A E" Nea Kavala Lagadikia E" Kavala (Perigiali) D Thessaloniki ALBANIA DÛ iavata Ipsala / Kipoi Û Alexandreia (G.Pelagou Camp) E" Û " D# " Û E A E Lagadikia ITALY E" Veria (Armatolou Kokkinou Camp) Thessaloniki E"Û D# Katerini Û Û Kato Mila (Pieria Ktima Iraklis) Moria Û E" Konitsa E" Û E" Kara Tepe E" Doliana GREECE Mytilene Û D# Û A Û Lesvos Agia Eleni E"D# Katsikas E" E" D# Larissa Katsikas D# Trikala Koutsochero (Efthimiopoulou camp) Û D# Karditsa Volos E"D# Volos PIKPA Û F Û Filipiada (Petropoulaki Camp) E" Û MoriaE"E#" ADF Lesvos PIKPA E"Û Thermopiles GREECE TURKEY Chios D# Chios Û Û # Û LivadiaD Û RitsonaÛ E" D# E" Elefsina (Merchant Marine Academy) E" OinÛ ofyta E" Chios Thiva (Former textile factory Sagiroglou) E" Vial GREECE Û E" Skaramagas port Athens (FO) Û " D# Vial E Û Kilkis AthÛ ens Elefsina (Merchant Marine Academy) Û Û Û Û E" E" D# Andravidas Û E" E" Eleonas A E" E"D#A Athens (FO) E" Schisto GREECE Samos Û Schisto Athens AthenÛ s ED#" Lavrio (Min. Agr. Summer Camp) E"F D# Tripoli Û Û Samos ED#" Leros # Samos D Lepida Û Û E" Vathy E" D# Kos Pyli GREECE Rhodes D#F D# Tilos Û GREECE National capital E" Refugee Center Leros Mediterranean D# A UNHCR Country Office F Refugee Location Û Leros Sea E" PIKPA Building A UNHCR Sub-Office D# Refugee Accomodation Lepida Û D# Chania E" D UNHCR Field Office Crossing point D# Heraklion Sitia D# UNHCR Field Unit International boundary 100km The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

![Duncan, Ifor. 2021. Hydrology of the Powerless. Doctoral Thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London [Thesis]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5057/duncan-ifor-2021-hydrology-of-the-powerless-doctoral-thesis-goldsmiths-university-of-london-thesis-4405057.webp)

Duncan, Ifor. 2021. Hydrology of the Powerless. Doctoral Thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London [Thesis]

Duncan, Ifor. 2021. Hydrology of the Powerless. Doctoral thesis, Goldsmiths, University of London [Thesis] https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/29967/ The version presented here may differ from the published, performed or presented work. Please go to the persistent GRO record above for more information. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Goldsmiths, University of London via the following email address: [email protected]. The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. For more information, please contact the GRO team: [email protected] HYDROLOGY OF THE POWERLESS Ifor Duncan Submitted To Goldsmiths, University Of London As Required For The Degree Of Doctor Of Philosophy Centre for Research Architecture Department of Visual Cultures Date: 30 September 2019 1 Declaration of Authorship I ____Ifor Duncan_______ hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented is largely my own but also contains research co-produced with colleague Stefanos Levidis, PhD Candidate (CRA). This is restricted to Part I: Fluvial Frontier. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ________ ______________ Date: 30/09/2019 2 Acknowledgements Firstly, I want to thank my supervisors Susan Schuppli and Ayesha Hameed for their continued support and insight, and for the inspiration I take from their research and profound practices. I would also like to thank Astrid Schmetterling, with whom I started this process, for her generosity and kindness. I would also like to thank the staff of Visual Cultures and CRA for all of their help and guidance over the years, as well my upgrade examiners Shela Sheikh and Richard Crownshaw. -

List of Refugee Deaths

List of 36 570 documented deaths of refugees and migrants due to the restrictive policies of "Fortress Europe" Documentation by UNITED as of 1 April 2019 Death by Policy - Time for Change! Campaign information: Facebook - UNITED Against Refugee Deaths, UnitedAgainstRefugeeDeaths.eu, [email protected], Twitter: @UNITED__Network #AgainstRefugeeDeaths UNITED for Intercultural Action, European network against nationalism, racism, fascism and in support of migrants and refugees Amsterdam secretariat: Postbus 413, NL-1000 AK Amsterdam, Netherlands, tel +31-6-48808808, [email protected], www.unitedagainstracism.org The UNITED List of Deaths can be freely re-used, translated and re-distributed, provided UNITED is informed in advance and source (UnitedAgainstRefugeeDeaths.eu) is mentioned. Researchers can obtain this list with more data in xls format from UNITED. found name, gender, age region of origin cause of death source dead number 28/03/19 2 N.N. (men) unknown drowned, bodies recovered off coast of Chios (GR), 36 rescued HelCoastG/IOM 27/03/19 1 Ali (boy, 18) Afghanistan suicide in shelter for unaccompanied minor asylum seekers in Geneva (CH), bad housing conditions Vivre/RTS/Le Courrier/TribuneGeneve 26/03/19 1 N.N. Sub-Saharan Africa drowned, found in advanced state of decomposition on beach near Tetouan, south of the Strait of Gibraltar (MA) El Pueblo de Ceuta/IOM 26/03/19 1 N.N. Sub-Saharan Africa drowned, found dead on beach in Azla (MA), presumably while trying to reach Spain FaroCeuta 26/03/19 1 N.N. Sub-Saharan Africa drowned, found floating in advanced state of decomposition in sea in Tarajal area of Ceuta (ES) FaroCeuta/Ceutaaldia/El Pueblo de Ceuta/IOM 26/03/19 4 N.N. -

Organization of Folk Athletic Games in Thrace

ORGANIZATION OF FOLK ATHLETIC GAMES IN THRACE Evangelos Albanidis, Dimitrios Goulimaris, Vasileios Serbezis Abstract: The aim of this paper is to study folk games which were organized by the Greek at cultural events in Thrace taking as its source the literature that has been published on the topic and fieldwork materials. Research has revealed that Thracians celebrated almost every festival and celebration with wrestling matches or a horse racing event. These spontaneous athletic games were con- nected with religion while these were often performed at religious festivals. The winners were mostly awarded lambs and goats, which were the offerings of believers to the church or offerings of shepherds for having had a good year and for their flocks. At special weddings, the Greek also organized horse races and wrestling matches. Key words: folk games, footraces, Greece, horse races, Thrace, wrestling matches INTRODUCTION Thrace is spread over three present-day countries: Greece, Turkey, and Bul- garia. The area has had no clearly defined boundaries ever since the ancient times. In the present study, Thrace is being studied in its greater national and geographical boundaries, those being the Struma (Strymōn) River to the west, the Danube to the north, the Thracian Sea to the south, and the Black Sea and Propontis (the Sea of Marmara) to the east (Oberhumer 1936: 394–396, Samsaris 1980: 13–17). Christian Thracians, who lived in North and East Thrace (present- day Bulgaria and Turkey, respectively) until 1923, had to abandon their home- land and settle mainly in West Thrace (present-day Greece) (Svolopoulos 2000: 265–266). -

World Bank Document

Documentof The World Bank FOROMCIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized RePoitNo. 6966 Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT GREECE EVROS DEVELOPMENT PROJECT LN. 1457-GR Public Disclosure Authorized October 14, 1987 Public Disclosure Authorized Agriculture Operations Country Department IV Europe, Middle East and North Africa Region dwhesk bm a ViieteddISebmot and may be Wedby ripietsony inthe ped.nunce of thai,oelal dutItm Uts cautentsmay noteebuiwh be disclosewithoust world Bank autheulzatlo. ABBREVIATIONS ABG - Agricultural Bank of Oreece DR - Drachma DEPO - Evros Development Project Office ERR - Economic Rate of Return ETVA - Hellenic Industrial Development Bank KYDEP - Central Organization for the Management of Agricultural Products PCR - Project Completion Report THEWOULD BANK Washington.D.C. 20433 U.SA Offieof DMI,.cttGwtai C'Postion.Ieatvawt Lctober 14, 1987 MEMORANDUMTO THE EXECUTIVEDIRECTORS AND THE PRESIDENT SUBJECTs Project CompletionReport on Greece Evros DevelopmentProject (Loan 1457-GR) Attachedt for information,is a copy of a report entitled 'Project CompletionReport on Greece Evros DevelopmentProject (Loan 1457-GR)lprepared by the Borrower,together with an OverviewMemorandum by the Europe,Middle East and North Africa RegionalOffice. Further evaluationof this project by the OperationsEvaluation Department has not been made. Attachment Thi docunnt has^"sftted distribution nd may be oW byre piattonlyi thed ptrfonmue of theirofcial duti Its contentsmy not otherwisebe dicose withoutWorld Bank authoration.