Patterned Ground in the Kharkhiraa Uul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

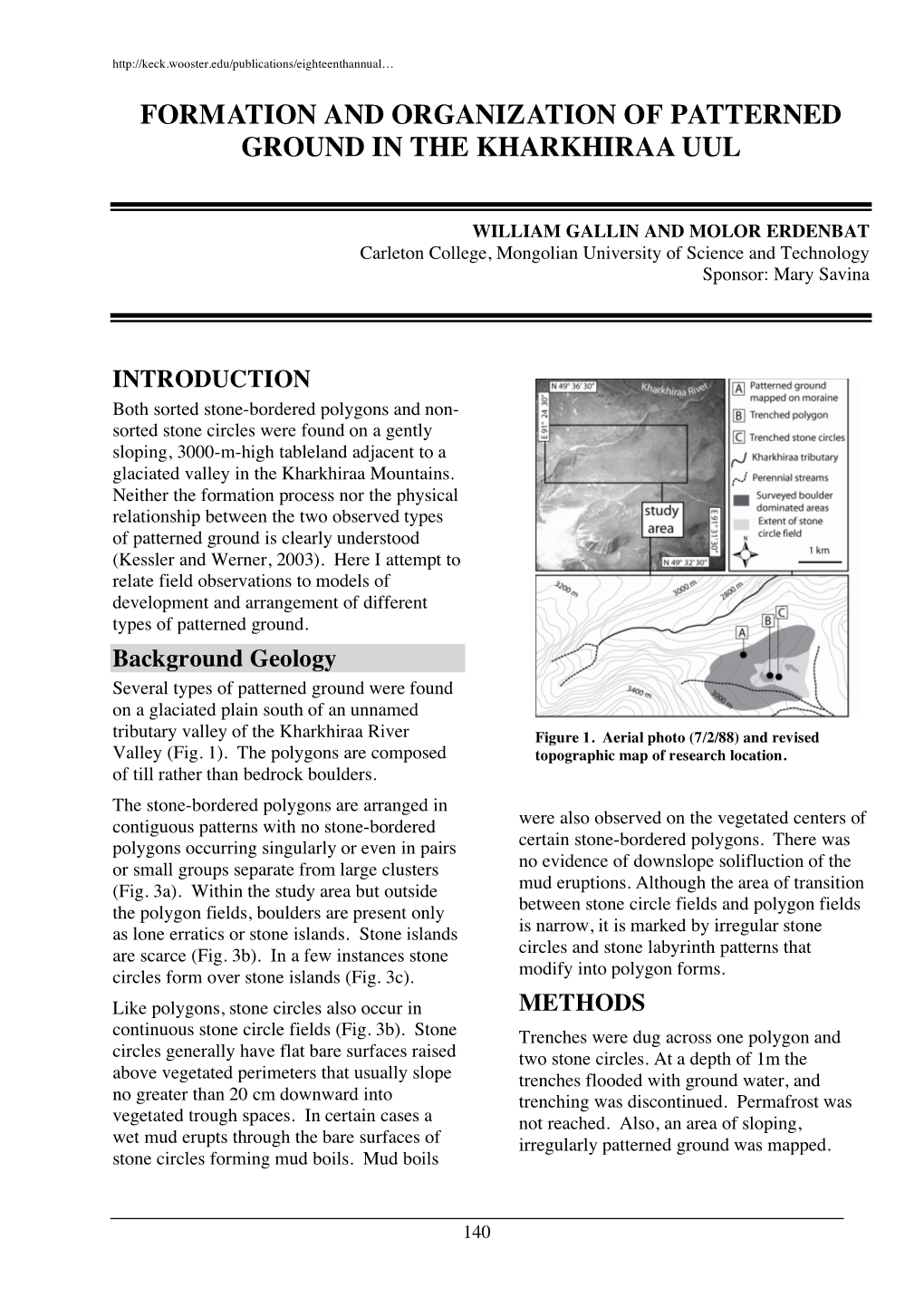

-

Response of CO2 Exchange in a Tussock Tundra Ecosystem to Permafrost Thaw and Thermokarst Development Jason Vogel,L Edward A

Response of CO2 exchange in a tussock tundra ecosystem to permafrost thaw and thermokarst development Jason Vogel,l Edward A. G. Schuur,2 Christian Trucco,2 and Hanna Lee2 [1] Climate change in high latitudes can lead to permafrost thaw, which in ice-rich soils can result in ground subsidence, or thermokarst. In interior Alaska, we examined seasonal and annual ecosystem CO2 exchange using static and automatic chamber measurements in three areas of a moist acidic tundra ecosystem undergoing varying degrees of permafrost thaw and thermokarst development. One site had extensive thermokarst features, and historic aerial photography indicated it was present at least 50 years prior to this study. A second site had a moderate number of thermokarst features that were known to have developed concurrently with permafrost warming that occurred 15 years prior to this study. A third site had a minimal amount of thermokarst development. The areal extent of thermokarst features reflected the seasonal thaw depth. The "extensive" site had the deepest seasonal thaw depth, and the "moderate" site had thaw depths slightly, but not significantly deeper than the site with "minimal" thermokarst development. Greater permafrost thaw corresponded to significantly greater gross primary productivity (GPP) at the moderate and extensive thaw sites as compared to the minimal thaw site. However, greater ecosystem respiration (Recc) during the spring, fall, and winter resulted in the extensive thaw site being a significant net source of CO2 to the atmosphere over 3 years, while the moderate thaw site was a CO2 sink. The minimal thaw site was near CO2 neutral and not significantly different from the extensive thaw site. -

Surficial Geology Investigations in Wellesley Basin and Nisling Range, Southwest Yukon J.D

Surficial geology investigations in Wellesley basin and Nisling Range, southwest Yukon J.D. Bond, P.S. Lipovsky and P. von Gaza Surficial geology investigations in Wellesley basin and Nisling Range, southwest Yukon Jeffrey D. Bond1 and Panya S. Lipovsky2 Yukon Geological Survey Peter von Gaza3 Geomatics Yukon Bond, J.D., Lipovsky, P.S. and von Gaza, P., 2008. Surficial geology investigations in Wellesley basin and Nisling Range, southwest Yukon. In: Yukon Exploration and Geology 2007, D.S. Emond, L.R. Blackburn, R.P. Hill and L.H. Weston (eds.), Yukon Geological Survey, p. 125-138. ABSTRACT Results of surficial geology investigations in Wellesley basin and the Nisling Range can be summarized into four main highlights, which have implications for exploration, development and infrastructure in the region: 1) in contrast to previous glacial-limit mapping for the St. Elias Mountains lobe, no evidence for the late Pliocene/early Pleistocene pre-Reid glacial limits was found in the study area; 2) placer potential was identified along the Reid glacial limit where a significant drainage diversion occurred for Grayling Creek; 3) widespread permafrost was encountered in the study area including near-continuous veneers of sheet-wash; and 4) a monitoring program was initiated at a recently active landslide which has potential to develop into a catastrophic failure that could damage the White River bridge on the Alaska Highway. RÉSUMÉ Les résultats d’études géologiques des formations superficielles dans le bassin de Wellesley et la chaîne Nisling peuvent être résumés en quatre principaux faits saillants qui ont des répercussions pour l’exploration, la mise en valeur et l’infrastructure de la région. -

Cold-Climate Landform Patterns in the Sudetes. Effects of Lithology, Relief and Glacial History

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS CAROLINAE 2000 GEOGRAPHICA, XXXV, SUPPLEMENTUM, PAG. 185–210 Cold-climate landform patterns in the Sudetes. Effects of lithology, relief and glacial history ANDRZEJ TRACZYK, PIOTR MIGOŃ University of Wrocław, Department of Geography, Wrocław, Poland ABSTRACT The Sudetes have the whole range of landforms and deposits, traditionally described as periglacial. These include blockfields and blockslopes, frost-riven cliffs, tors and cryoplanation terraces, solifluction mantles, rock glaciers, talus slopes and patterned ground and loess covers. This paper examines the influence, which lithology and structure, inherited relief and time may have had on their development. It appears that different rock types support different associations of cold climate landforms. Rock glaciers, blockfields and blockstreams develop on massive, well-jointed rocks. Cryogenic terraces, rock steps, patterned ground and heterogenic solifluction mantles are typical for most metamorphic rocks. No distinctive landforms occur on rocks breaking down through microgelivation. The variety of slope form is largely inherited from pre- Pleistocene times and includes convex-concave, stepped, pediment-like, gravitational rectilinear and concave free face-talus slopes. In spite of ubiquitous solifluction and permafrost creep no uniform characteristic ‘periglacial’ slope profile has been created. Mid-Pleistocene trimline has been identified on nunataks in the formerly glaciated part of the Sudetes and in their foreland. Hence it is proposed that rock-cut periglacial relief of the Sudetes is the cumulative effect of many successive cold periods during the Pleistocene and the last glacial period alone was of relatively minor importance. By contrast, slope cover deposits are usually of the Last Glacial age. Key words: cold-climate landforms, the Sudetes 1. -

Introduction to Foundations in Areas of Significant Frost Penetration

Introduction to Foundations in Areas of Significant Frost Penetration Course No: G03-003 Credit: 3 PDH J. Paul Guyer, P.E., R.A., Fellow ASCE, Fellow AEI Continuing Education and Development, Inc. 22 Stonewall Court Woodcliff Lake, NJ 07677 P: (877) 322-5800 [email protected] An Introduction to Foundations in Areas of Significant Frost Penetration Guyer Partners J. Paul Guyer, P.E., R.A. 44240 Clubhouse Drive El Macero, CA 95618 Paul Guyer is a registered mechanical (530) 758-6637 engineer, civil engineer, fire protection [email protected] engineer and architect with over 35 years experience in the design of buildings and related infrastructure. For an additional 9 years he was a principal advisor to the California Legislature on infrastructure and capital outlay issues. He is a graduate of Stanford University and has held numerous national, state and local offices with the American Society of Civil Engineers, Architectural Engineering Institute, and National Society of Professional Engineers. © J. Paul Guyer 2013 1 CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. FACTORS AFFECTING DESIGN OF FOUNDATIONS 3. SITE INVESTIGATIONS 4. FOUNDATION DESIGN (This publication is adapted from the Unified Facilities Criteria of the United States government which are in the public domain, have been authorized for unlimited distribution, and are not copyrighted.) (The figures, tables and formulas in this publication may at times be a little difficult to read, but they are the best available. DO NOT PURCHASE THIS PUBLICATION IF THIS LIMITATION IS NOT ACCEPTABLE TO YOU.) © J. Paul Guyer 2013 2 1. INTRODUCTION. 1.1 TYPES OF AREAS. For purposes of this manual, areas of significant frost penetration may be defined as those in which freezing temperatures occur in the ground to sufficient depth to be a significant factor in foundation design. -

Chapter 7 Seasonal Snow Cover, Ice and Permafrost

I Chapter 7 Seasonal snow cover, ice and permafrost Co-Chairmen: R.B. Street, Canada P.I. Melnikov, USSR Expert contributors: D. Riseborough (Canada); O. Anisimov (USSR); Cheng Guodong (China); V.J. Lunardini (USA); M. Gavrilova (USSR); E.A. Köster (The Netherlands); R.M. Koerner (Canada); M.F. Meier (USA); M. Smith (Canada); H. Baker (Canada); N.A. Grave (USSR); CM. Clapperton (UK); M. Brugman (Canada); S.M. Hodge (USA); L. Menchaca (Mexico); A.S. Judge (Canada); P.G. Quilty (Australia); R.Hansson (Norway); J.A. Heginbottom (Canada); H. Keys (New Zealand); D.A. Etkin (Canada); F.E. Nelson (USA); D.M. Barnett (Canada); B. Fitzharris (New Zealand); I.M. Whillans (USA); A.A. Velichko (USSR); R. Haugen (USA); F. Sayles (USA); Contents 1 Introduction 7-1 2 Environmental impacts 7-2 2.1 Seasonal snow cover 7-2 2.2 Ice sheets and glaciers 7-4 2.3 Permafrost 7-7 2.3.1 Nature, extent and stability of permafrost 7-7 2.3.2 Responses of permafrost to climatic changes 7-10 2.3.2.1 Changes in permafrost distribution 7-12 2.3.2.2 Implications of permafrost degradation 7-14 2.3.3 Gas hydrates and methane 7-15 2.4 Seasonally frozen ground 7-16 3 Socioeconomic consequences 7-16 3.1 Seasonal snow cover 7-16 3.2 Glaciers and ice sheets 7-17 3.3 Permafrost 7-18 3.4 Seasonally frozen ground 7-22 4 Future deliberations 7-22 Tables Table 7.1 Relative extent of terrestrial areas of seasonal snow cover, ice and permafrost (after Washburn, 1980a and Rott, 1983) 7-2 Table 7.2 Characteristics of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets (based on Oerlemans and van der Veen, 1984) 7-5 Table 7.3 Effect of terrestrial ice sheets on sea-level, adapted from Workshop on Glaciers, Ice Sheets and Sea Level: Effect of a COylnduced Climatic Change. -

The Influence of Shallow Taliks on Permafrost Thaw and Active Layer

PUBLICATIONS Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface RESEARCH ARTICLE The Influence of Shallow Taliks on Permafrost Thaw 10.1002/2017JF004469 and Active Layer Dynamics in Subarctic Canada Key Points: Ryan Connon1 , Élise Devoie2 , Masaki Hayashi3, Tyler Veness1, and William Quinton1 • Shallow, near-surface taliks in subarctic permafrost environments 1Cold Regions Research Centre, Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2Department of Civil and fl in uence active layer thickness by 3 limiting the depth of freeze Environmental Engineering, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, Department of Geoscience, University of • Areas with taliks experience more Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada rapid thaw of underlying permafrost than areas without taliks • Proportion of areas with taliks can Abstract Measurements of active layer thickness (ALT) are typically taken at the end of summer, a time increase in years with high ground synonymous with maximum thaw depth. By definition, the active layer is the layer above permafrost that heat flux, potentially creating tipping point for permafrost thaw freezes and thaws annually. This study, conducted in peatlands of subarctic Canada, in the zone of thawing discontinuous permafrost, demonstrates that the entire thickness of ground atop permafrost does not always refreeze over winter. In these instances, a talik exists between the permafrost and active layer, and ALT Correspondence to: must therefore be measured by the depth of refreeze at the end of winter. As talik thickness increases at R. Connon, the expense of the underlying permafrost, ALT is shown to simultaneously decrease. This suggests that the [email protected] active layer has a maximum thickness that is controlled by the amount of energy lost from the ground to the atmosphere during winter. -

Geophysical Mapping of Palsa Peatland Permafrost

The Cryosphere, 9, 465–478, 2015 www.the-cryosphere.net/9/465/2015/ doi:10.5194/tc-9-465-2015 © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Geophysical mapping of palsa peatland permafrost Y. Sjöberg1, P. Marklund2, R. Pettersson2, and S. W. Lyon1 1Department of Physical Geography and the Bolin Centre for Climate Research, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden 2Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden Correspondence to: Y. Sjöberg ([email protected]) Received: 15 August 2014 – Published in The Cryosphere Discuss.: 13 October 2014 Revised: 3 February 2015 – Accepted: 10 February 2015 – Published: 4 March 2015 Abstract. Permafrost peatlands are hydrological and bio- ing in these landscapes are influenced by several factors other geochemical hotspots in the discontinuous permafrost zone. than climate, including hydrological, geological, morpholog- Non-intrusive geophysical methods offer a possibility to ical, and erosional processes that often combine in complex map current permafrost spatial distributions in these envi- interactions (e.g., McKenzie and Voss, 2013; Painter et al., ronments. In this study, we estimate the depths to the per- 2013; Zuidhoff, 2002). Due to these interactions, peatlands mafrost table and base across a peatland in northern Swe- are often dynamic with regards to their thermal structures and den, using ground penetrating radar and electrical resistivity extent, as the distribution of permafrost landforms (such as tomography. Seasonal thaw frost tables (at ∼ 0.5 m depth), dome-shaped palsas and flat-topped peat plateaus) and talik taliks (2.1–6.7 m deep), and the permafrost base (at ∼ 16 m landforms (such as hollows, fens, and lakes) vary with cli- depth) could be detected. -

Periglacial Processes, Features & Landscape Development 3.1.4.3/4

Periglacial processes, features & landscape development 3.1.4.3/4 Glacial Systems and landscapes What you need to know Where periglacial landscapes are found and what their key characteristics are The range of processes operating in a periglacial landscape How a range of periglacial landforms develop and what their characteristics are The relationship between process, time, landforms and landscapes in periglacial settings Introduction A periglacial environment used to refer to places which were near to or at the edge of ice sheets and glaciers. However, this has now been changed and refers to areas with permafrost that also experience a seasonal change in temperature, occasionally rising above 0 degrees Celsius. But they are characterised by permanently low temperatures. Location of periglacial areas Due to periglacial environments now referring to places with permafrost as well as edges of glaciers, this can account for one third of the Earth’s surface. Far northern and southern hemisphere regions are classed as containing periglacial areas, particularly in the countries of Canada, USA (Alaska) and Russia. Permafrost is where the soil, rock and moisture content below the surface remains permanently frozen throughout the entire year. It can be subdivided into the following: • Continuous (unbroken stretches of permafrost) • extensive discontinuous (predominantly permafrost with localised melts) • sporadic discontinuous (largely thawed ground with permafrost zones) • isolated (discrete pockets of permafrost) • subsea (permafrost occupying sea bed) Whilst permafrost is not needed in the development of all periglacial landforms, most periglacial regions have permafrost beneath them and it can influence the processes that create the landforms. Many locations within SAMPLEextensive discontinuous and sporadic discontinuous permafrost will thaw in the summer months. -

Cold Season Emissions Dominate the Arctic Tundra Methane Budget

Cold season emissions dominate the Arctic tundra methane budget Donatella Zonaa,b,1,2, Beniamino Giolic,2, Róisín Commaned, Jakob Lindaasd, Steven C. Wofsyd, Charles E. Millere, Steven J. Dinardoe, Sigrid Dengelf, Colm Sweeneyg,h, Anna Kariong, Rachel Y.-W. Changd,i, John M. Hendersonj, Patrick C. Murphya, Jordan P. Goodricha, Virginie Moreauxa, Anna Liljedahlk,l, Jennifer D. Wattsm, John S. Kimballm, David A. Lipsona, and Walter C. Oechela,n aDepartment of Biology, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA 92182; bDepartment of Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield, Sheffield S10 2TN, United Kingdom; cInstitute of Biometeorology, National Research Council, Firenze, 50145, Italy; dSchool of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138; eJet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91109-8099; fDepartment of Physics, University of Helsinki, FI-00014 Helsinki, Finland; gCooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80304; hEarth System Research Laboratory, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Boulder, CO 80305; iDepartment of Physics and Atmospheric Science, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada B3H 4R2; jAtmospheric and Environmental Research, Inc., Lexington, MA 02421; kWater and Environmental Research Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK 99775-7340; lInternational Arctic Research Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK 99775-7340; mNumerical Terradynamic Simulation -

Permafrost Soils and Carbon Cycling

SOIL, 1, 147–171, 2015 www.soil-journal.net/1/147/2015/ doi:10.5194/soil-1-147-2015 SOIL © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Permafrost soils and carbon cycling C. L. Ping1, J. D. Jastrow2, M. T. Jorgenson3, G. J. Michaelson1, and Y. L. Shur4 1Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station, Palmer Research Center, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 1509 South Georgeson Road, Palmer, AK 99645, USA 2Biosciences Division, Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL 60439, USA 3Alaska Ecoscience, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA 4Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA Correspondence to: C. L. Ping ([email protected]) Received: 4 October 2014 – Published in SOIL Discuss.: 30 October 2014 Revised: – – Accepted: 24 December 2014 – Published: 5 February 2015 Abstract. Knowledge of soils in the permafrost region has advanced immensely in recent decades, despite the remoteness and inaccessibility of most of the region and the sampling limitations posed by the severe environ- ment. These efforts significantly increased estimates of the amount of organic carbon stored in permafrost-region soils and improved understanding of how pedogenic processes unique to permafrost environments built enor- mous organic carbon stocks during the Quaternary. This knowledge has also called attention to the importance of permafrost-affected soils to the global carbon cycle and the potential vulnerability of the region’s soil or- ganic carbon (SOC) stocks to changing climatic conditions. In this review, we briefly introduce the permafrost characteristics, ice structures, and cryopedogenic processes that shape the development of permafrost-affected soils, and discuss their effects on soil structures and on organic matter distributions within the soil profile. -

D3.1 Palsa Mire

European Red List of Habitats - Mires Habitat Group D3.1 Palsa mire Summary Palsa mire develops where thick peat is subject to sporadic permafrost in Iceland, northern Fennoscandia and arctic Russia where there is low precipitation and an annual mean temperature below -1oC. The permafrost dynamics produce a typical patterning with palsa mounds 2-4m (sometimes 7m) high elevated in central thicker areas by permafrost lenses, the carpet of Sphagnum peat limiting the penetration of thaw, and a perennially frozen core of peat, silt and ice lenses beneath. Pounikko hummock ridges can be found in marginal areas subject to seasonal freezing and there are plateau-wide palsas and pounu string mires in the arctic. Intact palsa mounds show a patterning of weakly minerotrophic vegetation with different assemblages of mosses, herbs and sub-shrubs on their tops and sides. Old palsa mounds can become dry and erosion may lead to melting and collapse. Complete melting leaves behind thermokarst ponds. Palsa mires have experienced substantial decline and deterioration in recent years and, although these changes are not yet dramatic, all estimations indicate high probability of collapse as a result of climatic warming. Climate change mitigation measures are decisive to prevent the collapse of this habitat type. Synthesis This habitat type is assessed as Critically Endangered (CR) under Criterion E as its probability of collapse within the next 50 years is estimated to be over 50% as a result of climate warming. This quantitative analysis has been performed by reviewing and analyzing published research articles, together with unpublished contributions from experts, by including probabilistic modeling of future trends and linear extrapolation of recent trends to support model predictions. -

Response of Methane and Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Peatlands to Permafrost Thawing in Xiaoxing’An Mountains, Northeast China

atmosphere Article Response of Methane and Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Peatlands to Permafrost Thawing in Xiaoxing’an Mountains, Northeast China Xiaoxin Sun 1,2, Hongjun Wang 3 , Changchun Song 4, Xin Jin 1, Curtis J. Richardson 3 and Tijiu Cai 1,2,* 1 Key Laboratory of Sustainable Forest Ecosystem Management-Ministry of Education, School of Forestry, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin 150040, China; [email protected] (X.S.); [email protected] (X.J.) 2 Heilongjiang Sanjiang Plain Wetland Ecosystem Research Station, Fuyuan 156500, China 3 Duke University Wetland Center, Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, USA; [email protected] (H.W.); [email protected] (C.J.R.) 4 Northeast Institute of Geography and Agroecology, Chinese Academy of Science, Changchun 130102, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Permafrost thawing may lead to the release of carbon and nitrogen in high-latitude regions of the Northern Hemisphere, mainly in the form of greenhouse gases. Our research aims to reveal the effects of permafrost thawing on CH4 and N2O emissions from peatlands in Xiaoxing’an Mountains, Northeast China. During four growing seasons (2011–2014), in situ CH4 and N2O emissions were monitored from peatland under permafrost no-thawing, mild-thawing, and severe- thawing conditions in the middle of the Xiaoxing’an Mountains by a static-chamber method. Average CH4 emissions in the severe-thawing site were 55-fold higher than those in the no-thawing site. The seasonal variation of CH4 emission became more aggravated with the intensification of permafrost Citation: Sun, X.; Wang, H.; Song, C.; thawing, in which the emission peaks became larger and the absorption decreased to zero.