Full Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HEVAN of UTTARAKHAND ( Mussoorie - Haridwar - Rishikesh - Chopta - Auli)

ी गणेशाय नमः 08 NIGHT / 09 DAYS (Ex. Delhi) HEVAN OF UTTARAKHAND ( Mussoorie - Haridwar - Rishikesh - Chopta - Auli) * * 02 Night Mussoorie - 01 Night Rudraprayag - 02 Night Joshimath - 01 Night Rishikesh - 01 Night Haridwar - 01 Night Delhi * * * 206, SAIGIRI APARTMENT, SAIBABA NAGAR, NAVGHAR ROAD, BHAYANDER(E), MUMBAI - 401105 Phone: - 09321590898 / 09322590898 /09323790898, - 022 - 28190898 Website - www.kanaiyatravels.com / www.uncleTours.com. / Email - [email protected] * Days Tour Detail SPECIAL DISCOUNT Day 01 : DELHI TO MUSSOORIE(280 KM / 8 -9 Hrs) ON GROUP BOOKING Pick Up From New Delhi Railway Station / Airport at Morning and proceed to Mussoorie (9-10 hrs. Now also available on journey). Evening visit Mall Road for shopping. Night halt at Mussoorie. EMI facility (The passengers who are directly reaching Haridwar by train will be picked up at 15.00 pm. & Passengers who reach Dehradun by direct flight / Train will be picked up at 16.00 pm.) DEPARTURE DATE Day 02 : MUSSOORIE SIGHTSEEING Wake up early in the morning and enjoy a nature walk at the mall road. Have your hot and PLEASE CALL 9322590898 delicious breakfast at the hotel. Post breakfast proceeds to explore Kempty falls, Devbhumi wax 9321590898 museum, Mussoorie lake, Camels back road, Cloud’s end, and Bhatta falls. Lunch during the sightseeing. Evening return back to the hotel. Evening explores Gun Hills by ropeway on your own from the Mall Road. Dinner and overnight stay at the Mussoorie. Day 03 : MUSSOORIE TO CHOPTA (185 KM / 7 Hrs) Wake up, Get refreshed and refuel yourself with a heavy breakfast. Check out at 08.30 AM from the hotel and proceeds to Rudraprayag via covering Surkanda Devi temple, Eco Park, Dhanaulti, Kanatal, Chamba, New Tehri, Srinagar, and Rudraprayag on the way. -

A Case of Community Based Ecotourism in the Himalayas

ECOLOGICAL IDIOSYNCRASY: A CASE OF COMMUNITY BASED ECOTOURISM IN THE HIMALAYAS Dhiraj Pathak1, Gaurav Bathla2, Shashi K Tiwari3 1Assistant Professor and HOD, Faculty of Hospitality, GNA University, Phagwara (India) 2Assistant Professor, Faculty of Hospitality, GNA University, Phagwara (India) 3Associate Professor, Faculty of Hospitality, GNA University, Phagwara (India) I INTRODUCTION Community-based ecotourism is a form of ecotourism that emphasizes the development of local communities and allows for local residents to have substantial control over, and involvement in; its development and management, and a major proportion of the benefits remain within the community. Community-based ecotourism should foster sustainable use and collective responsibility, but it also embraces individual initiatives within the community. With this form of ecotourism, local residents share the environment and their way of life with visitors, while increasing local income and building local economies. By sharing activities such as festivals, homestays, and the production of artisan goods, community-based ecotourism allows communities to participate in the modern global economy while cultivating a sustainable source of income and maintaining their way of life. A successful model of community-based ecotourism works with existing community initiatives, utilizes community leaders, and seeks to employ local residents so that income generated from ecotourism stays in the community and maximizes local economic benefits. Although ecotourism often promises community members improved livelihoods and a source of employment, irresponsible ecotourism practices can exhaust natural resources and exploit local communities. It is essential that approaches to community-based ecotourism projects be a part of a larger community development strategy and carefully planned with community members to ensure that desired outcomes are consistent with the community’s culture and heritage. -

Sustainable Tourism Development : Potential of Home Stay Business in Uttarakhand

IJMRT • Volume 13 • Number 1 • January-June 2019: 51-63 SUSTAINABLE TOURISM DEVELOPMENT : POTENTIAL OF HOME STAY BUSINESS IN UTTARAKHAND Dr. Anupama Srivastava1 & Sanjay Singh2 Abstract: Tourism has emerged as one of the most important industry of the future. The Multiplier effects of tourism in terms of employment generation, income generation, development of tourism infrastructure and also conservation of priceless heritage, cultural deposits and development of potential tourism places are significant. Uttaranchal remains as one of the greatest attractions for tourists and state has tremendous potential for future tourism development. Moreover, tourism as a socio-economic activity involves a variety of services and deals basically with human beings moving from one place to another for different motivation to fulfill varied objectives. There are a number of eco-tourism destinations including national parks and wildlife sanctuaries in the state of Uttarakhand which attract nature lovers. Against this backdrop, present paper purports to examine the scope of home stay tourism in The state of Uttarkhand. INTRODUCTION The State of Uttarakhand comprises of 13 districts that are grouped into two regions (Kumaon and Garhwal) and has a total geographical area of 53,484 sq. km. The State has a population of 101.17 million (Census of India, 2011) of which the rural population constitutes about 70 percent of the total. Uttarakhand is the 20th most populous state of the country. The economy of the State primarily depends on agriculture and tourism. About 70 percent of the population is engaged in agriculture. Out of the total reported area, only 14% is under cultivation. More than 55 percent of the cultivated land in the State is rain-fed. -

Download Download

ISSN: 2322 - 0902 (P) ISSN: 2322 - 0910 (O) International Journal of Ayurveda and Pharma Research Research Article ETHNO-BOTANICAL IDENTIFICATION OF SOME WILD HERB SPECIES OF SURKANDA DEVI HILL, UTTARAKHAND Arya Rishi1*, Singh D.C2, Tiwari R.C3, Naithani Harsh Bardhan4 *1P.G Scholar, 2Professor, Department of Dravyaguna, Uttrakhand Ayurveda University, Rishikul Campus, Haridwar, Uttrakhand, India. 3Associate Professor, Department of Agada Tantra, Uttrakhand Ayurveda University, Rishikul Campus, Haridwar, Uttrakhand, India. 4Consultant Lead Taxonomist, Botany Division, FRI, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India. ABSTRACT Medicinal plants play important role in healthcare practices among the tribal's and rural people. These Tribal's and rural people have wonderful knowledge about the effective treatment of many health problems only by using the plant parts. This knowledge acquired by the tribal's and rural peoples usually passed from generation to generation only in verbal form. So an effort was carried out to assess ethno botanical information of some wild herb species used by the local dwellers of Surkanda Devi Hill in District Tehri Garhwal of Uttarakhand. The information presented in this paper was gathered by frequent field visit in the forest and adjoining villages, participatory observations, group discussion, interviews with local knowledgeable people residing nearby Surkanda Devi Temple from September 2014 to March 2016. A total of 60 plant species were collected during the field visit out of which 48 plant species under 41 genera and 30 families were reported ethno-medicinal by the local dwellers and used by them for their primary health care. The plants used for different purposes are listed with scientific name, family, local name, ethno-medicinal importance. -

Initial Environment Examination IND:Uttarakhand Emergency Assistance Project (UEAP)

Initial Environment Examination Project Number: 47229-001 November 2016 IND: Uttarakhand Emergency Assistance Project (UEAP) Package: UEAP/PWD/C-104, UEAP/PWD/C-105 and UEAP/PWD/C-107 Submitted by Project implementation Unit –UEAP (Roads and Bridges), Dehradun This initial environment examination report has been submitted to ADB by the Project implementation Unit – UEAP (Roads and Bridges), Dehradun and is made publicly available in accordance with ADB’s Public Communications Policy (2011). It does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB. This initial environment examination report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Initial Environmental Examination October 2016 India: Uttarakhand Emergency Assistance Project 1- Protection/Treatment work on Chronic land slide zone on Haripur – Ichari – Kwanu – Meenus Motor Marg (Km 33) PACKAGE NO.: UEAP/PWD/C-104 2- Protection/Treatment work on Chronic Landslide Zone Pipaldali - Rajakhet Motor Marg Km-1, District Tehri in Uttarakhand, PACKAGE NO.: UEAP/PWD/C- 105 3- Protection/Treatment work on Chronic Landslide Zone Pratapnagar-Tehri Motor Marg Km-19, District Tehri in Uttarakhand, PACKAGE NO.: UEAP/PWD/C-107 Prepared by State Disaster Management Authority, Government of Uttarakhand, for the Asian Development Bank. -

(ECO-TOURISM) in UTTARAKHAND Analysis and Recommendations

RURAL DEVELOPMENT AND MIGRATION COMMISSION UTTARAKHAND, PAURI NATURE BASED TOURISM (ECO-TOURISM) IN UTTARAKHAND Analysis and recommendations SEPTEMBER 2018 PREFACE Uttarakhand, located in the western Himalayan region, is largely mountainous with bulk of its population living in the rural areas. Migration of people from rural to semi-urban or urban areas particularly from the hill districts is a major cause for concern, as it results in depopulated or partially depopulated villages; and a dwindling primary sector (agriculture). Out migration from the rural areas of the state is posing multiple challenges causing economic disparities; declining agriculture; low rural incomes and a stressed rural economy. It is in this background that the Uttarakhand government decided to set up a commission to assess the quantum and extent of out migration from different rural areas of the state; evolve a vision for the focused development of the rural areas, that would help in mitigating out-migration and promote welfare and prosperity of the rural population; advise the government on multi-sectoral development at the grassroots level which would aggregate at the district and state levels; submit recommendations on those sections of the population of the state that is at risk of not adequately benefitting from economic progress and to recommend and monitor focused initiatives in sectors that would help in multi-sectoral development of rural areas and thus help in mitigating the problem of out-migration. The commission chaired by the Chief Minister of the state , presented its first report to the government in the first half of 2018 in which various aspects of out migration have been brought out on the basis of a detailed ground level survey and detailed consultations with various stakeholders. -

Kanatal - Rishikesh

DELHI - KANATAL - RISHIKESH Distance to Kanatal : 325 kms. (7 to 8 hrs drive) - Route : Delhi - Meerut - Muzaffarnagar - Roorkee - Haridwar - Rishikesh - Narendra Nagar - Chamba - Kanatal (On Chamba - Mussorie Road) USP of Kanatal - At 8500 ft above sea level, secluded, Awesome view of Himalayas. Clear view of Trishul, Chaukhamba and Bandarpoonch. Lots of trekking options in Kodia Jungle. Pine and Oak forest. Places to See - Kodia Jungle, Tehri Dam, Dhanolti - Surkanda devi temple, ECO Park. Road Condition - Road after Muzaffarnagar to Roorkee is bad. High traffic in Haridwar and Roorkee. Midway Break - Namaste Midway has MCD, Haldiram, Costa, Baskin and Robins is about 5 kms before Muzaffarnagar and an ideal stop over. Of course Cheetal Grand is also another option which is 12 km before Midway. Stay - 3 nights at Kanatal Club Mahindra. 1 night stay at Rishikesh GMVN Rishilok Tourist Rest House. The Journey We started by 5.30 Am. By 7.30 am we reached MCD. 10 am we were in Haridwar and by 1 pm reached Kanatal. Day - 1 Check in was smooth and post lunch we lazed around for the day... The resort is on the main Chamba - Dhanaulti road. Medium sized resort with about 35 rooms. All rooms are valley facing. Well appointed rooms with good insulation and room heating . Evenings and early morning are cold and some times windy too. The hotel is just infront of Kodia eco park. Food is pricey but members have discount and fun dining option. Monkey menace a problem. Day-2 We planned to trek Kodia Jungle. Morning trek was about 7 kms. -

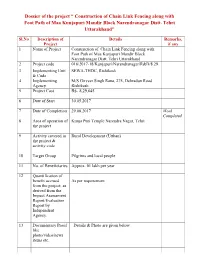

Dossier of the Project “ Construction of Chain Link Fencing Along with Foot Path of Maa Kunjapuri Mandir Block Narendranagar Distt

Dossier of the project “ Construction of Chain Link Fencing along with Foot Path of Maa Kunjapuri Mandir Block Narendranagar Distt. Tehri Uttarakhand” Sl.No Description of Details Remarks, Project if any 1 Name of Project Construction of Chain Link Fencing along with Foot Path of Maa Kunjapuri Mandir Block Narendranagar Distt. Tehri Uttarakhand 2 Project code 016/2017-18/Kunjapuri/Narendranagar/R&D/8.29 3 Implementing Unit SEWA-THDC, Rishikesh & Code 4 Implementing M/S Girveer Singh Rana, 275, Dehradun Road Agency Rishikesh 5 Project Cost Rs. 8,29,645 6 Date of Start 30.05.2017 7 Date of Completion 29.08.2017 Work Completed 8 Area of operation of Kunja Puri Temple Narendra Nagar, Tehri the project 9 Activity covered in Rural Development (Utthan) the project & activity code 10 Target Group Pilgrims and local people 11 No. of Beneficiaries Approx. 01 lakh per year 12 Quantification of benefit accrued As per requirement from the project, as derived from the Impact Assessment Report/Evaluation Report by Independent Agency. 13 Documentary Proof Details & Photo are given below like photo/video/news items etc. Introduction: Kunjapuri Devi Temple is a renowned Temple of High Religious Importance to Pilgrims of Hindu Religion. The Holy Shrine is Located at an altitudinal Height of 1,676 Meters above the sea level. The Temple is one of the 52 Shakti peeths in Uttarakhand and is a place where the chest of the Burnt Sati fell down. Kunjapuri Devi Temple offers Panoramic views of snow laden mountains such as Gangotri, Banderpooch, Swarga Rohini and chaukhamba. -

Patients and Healers: Medical Anthropology 1

Himalayan Geography: History, Society and Culture Spring 2020, ANTH 0730 Mr. Akshay Shah Hanifl Center Day “D” During Expeditions 1 COURSE STRUCTURE This course involves engaged participation in each of the expeditions/special programs that are featured on the itinerary for Pitt in the Himalayas 2020. Each of the field trips, as outlined below, will count as a class meeting. Instruction during each field trip will be intensively experiential, with a focus on directed field-based learning. The course is required for all students enrolled in Pitt in the Himalayas. COURSE BACKGROUND The Himalayan region is characterized by a tremendous range of social and cultural diversity that corresponds to climatic, ecological and geographical variation, as well as local and regional geopolitical factors. Historical change from the emergence of early forms of social complexity centered on chiefs and their forts – from which the regional designation of “Garhwal” takes its name – through the development of kingdoms and larger polities shows the intimate link between geography, environment and socio-political transformation. Similarly, local language patterns, regional religious practices, musical styles, mythology, food culture, sartorial fashion, architectural design, agricultural and transportation technologies and engineering and trade networks have all been shaped by the structure of mountain barriers, bounded valley communities and bracketed lines of communication that follow river systems. Whereas the political economy of the Himalayas has been structured around agricultural production, and the development of elaborate field terrace systems, there have also been subsidiary economies centered on trans-Himalayan trade and pilgrimage as well as pastoral nomadism and transhumance. Since the colonial period, the Himalayas have increasingly become a place for rest, relaxation, tourism and adventure, and this – along with further political transformations since Indian independence -- has lead to the rapid development of urban areas. -

UCOST Sponsored Research and Development Projects

UCOST Sponsored Research and Development Projects Assessment of potential of cyanobacterial isolates from Garhwal region for the production of phycobiliproteins PI— Dr Vidya Dhar Pandey Cyanobacteria (Blue-green algae), the organisms investigated for the present study, are a morphologically diverse and ubiquitous group of photosynthetic prokaryotes with potential applications in various fields, such as agriculture, aquaculture, nutraceuticals, pharmaceuticals, bioenergy and bioremediation. They produce fluorescent accessory photosynthetic pigments, called phycobiliproteins (PBPs), which are industrially and pharmacologically important natural products. The potential use of phycobiliproteins as non-toxic and non-carcinogenic natural food colorants/additives has been recognised world-wide in view of the toxicity and carcinogenicity of widely used synthetic food colorants/additives. They also find applications in cosmetics and clinical diagnostics. Moreover, they exhibit pharmacologically important activities, such as anticancerous, antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective and hepatoprotective. Because of their rapid growth rate, simple growth requirements, amenability to controlled laboratory culture and ubiquity, cyanobacteria comprise a suitable bioresource for phycobiliproteins. Although cyanobacteria are widely distributed organisms with remarkable ability to grow and survive under varied climatic/environmental conditions, hitherto they represent unexplored or meagerly explored organisms in Uttarakhand. Cyanobacterial samples -

Tarab Ling Facilitating Trekking and Outings

Tarab Ling Facilitating trekking and outings In the following you can see some suggestions for trekking in the higher mountains. There are also very nice walks all year round out of Tarab Ling for half a day or a full day to nearby hills, villages and waterfalls. Or you may take walks out from the nearby hill station, Mussoorie, and spend a night or two there. There are many options around Dehradun and if you like to arrange in advance please contact: Norbu Wangchuk, General Secretary Tarab Ling Association Asthal, P.O Maldevta Maldevta-Raipur Road Dehradun -248001 Uttarakhand, India Contact phone: (0091) 91 941 018 6214 / 999 7679 245 Email:[email protected] Web: http://tarab-institute.org HIGHER HIMLAYAN TREKKINGS (May to October) 1. CAMP BUGYAL SARAI Nestled between the foothills of the Himalayas and the lively village of Barsu, Camp Bugyal Sarai is a Himalayan paradise like no other. Whether it is a trek, a hike, a scenic vista or a relaxing afternoon in the wilderness that you seek, Barsu has it all. A day at Bugyal Sarai has endless possibilities, leaving the traveler toiling over how best to spend their day. Flora and fauna abound, making any hike a snail’s pace effort to soak in the Himalayan scenery. • The camp is a perfect jumping off point for a Himalayan trek for the adventurer or a simple, rustic getaway for the traveler seeking solace and relaxation. With a helpful and accommodating staff, full and eco-friendly facilities and a lovely touch of the local Himalayan culture, Bugyal Sarai is as versatile as its visitors—artists, yogis, climbers, hikers, writers, thinkers, and people of the world alike. -

Development of Adventure Tourism in Northern India : a Case Study of Uttrakhand

/ \ \ ✓ us rz 7G DEVELOPMENT OF ADVENTURE TOURISM IN NORTHERN INDIA : A CASE STUDY OF UTTRAKHAND THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF doctor of Vbilo0pbp IN COMMERCE (TOURISM) SAADIA LODI t rl Under the Supervision of Dr. SHEEBA HAMID (Associate Professor) [7T7?. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2013 14 NCV 2?14 k 1I1I 1 IU 1111k k\I1k Il III Department of Commerce on sheeba Hamid Aligarh Muslim University, .17A, (ph. (D. Aligarh. Associate (Professor (Tourism)'~'~-~' } Internal: 3505, 3506 Training a cPCPlaccement Officer External: 0571-2703661 Master of Tourism Administration (MTA) Qtertifttate This is to certify that the work embodied, in this thesis entitled "Development of Adventure Tourism in Northern India: A Case Study of (Jltrakhand" is the original work to the best of my knowledge. It has been carried out by Ms. Saadia Lodi, under my supervision and is suitable for submission for the award of Ph.D degree in Commerce (Tourism) of Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh. br. Shee a Hamid (Associat4 Professor) 'Mussoorie Cottage', 4/1286-A, Sir Syed Nagar, Aligarh — 202002 Res: +91-571-2407861, Cell: +91-9319926119 E-mail: [email protected] LIST OF CONTENTS Page No. Preface i-iv Acknowledgements v-vii List of Tables viii-x List of Figures xi List of Abbreviations xii-xiii Chapter-1: Introductory Background and Framework 1-35 of the Study (Section: A) 1. Introductory Background 1-2 2. India: A Background vis-a-vis Tourism 2-3 3. What is Adventure Tourism? 3-4 4. Uttarakhand: Adventure Tourism Destination 4 (Section: B) 5.