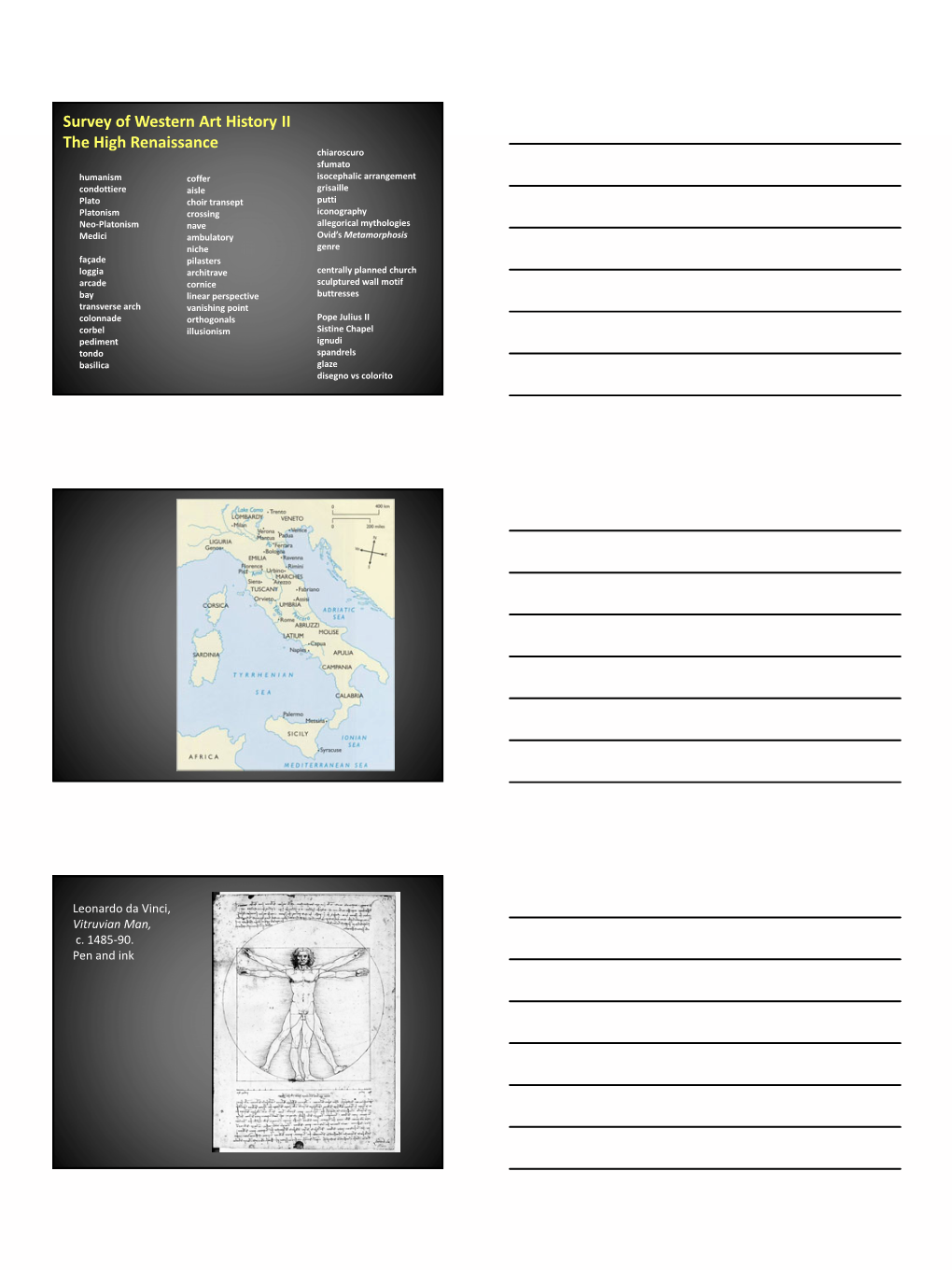

Survey of Western Art History II the High Renaissance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

Janson. History of Art. Chapter 16: The

16_CH16_P556-589.qxp 12/10/09 09:16 Page 556 16_CH16_P556-589.qxp 12/10/09 09:16 Page 557 CHAPTER 16 CHAPTER The High Renaissance in Italy, 1495 1520 OOKINGBACKATTHEARTISTSOFTHEFIFTEENTHCENTURY , THE artist and art historian Giorgio Vasari wrote in 1550, Truly great was the advancement conferred on the arts of architecture, painting, and L sculpture by those excellent masters. From Vasari s perspective, the earlier generation had provided the groundwork that enabled sixteenth-century artists to surpass the age of the ancients. Later artists and critics agreed Leonardo, Bramante, Michelangelo, Raphael, Giorgione, and with Vasari s judgment that the artists who worked in the decades Titian were all sought after in early sixteenth-century Italy, and just before and after 1500 attained a perfection in their art worthy the two who lived beyond 1520, Michelangelo and Titian, were of admiration and emulation. internationally celebrated during their lifetimes. This fame was For Vasari, the artists of this generation were paragons of their part of a wholesale change in the status of artists that had been profession. Following Vasari, artists and art teachers of subse- occurring gradually during the course of the fifteenth century and quent centuries have used the works of this 25-year period which gained strength with these artists. Despite the qualities of between 1495 and 1520, known as the High Renaissance, as a their births, or the differences in their styles and personalities, benchmark against which to measure their own. Yet the idea of a these artists were given the respect due to intellectuals and High Renaissance presupposes that it follows something humanists. -

Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Italian Renaissance: Envisioning Aesthetic Beauty and the Past Through Images of Women

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2010 DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN Carolyn Porter Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/113 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Carolyn Elizabeth Porter 2010 All Rights Reserved “DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN” A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University. by CAROLYN ELIZABETH PORTER Master of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2007 Bachelor of Arts, Furman University, 2004 Director: ERIC GARBERSON ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia August 2010 Acknowledgements I owe a huge debt of gratitude to many individuals and institutions that have helped this project along for many years. Without their generous support in the form of financial assistance, sound professional advice, and unyielding personal encouragement, completing my research would not have been possible. I have been fortunate to receive funding to undertake the years of work necessary for this project. Much of my assistance has come from Virginia Commonwealth University. I am thankful for several assistantships and travel funding from the Department of Art History, a travel grant from the School of the Arts, a Doctoral Assistantship from the School of Graduate Studies, and a Dissertation Writing Assistantship from the university. -

Titian and Veronese Two Venetian Painters

Titian and Veronese Two Venetian Painters Titian Veronese Garry Law Sack of Rome 1527 – end of the Renaissance in Rome Timeline and Contemporaries / Predecessors Titian - ~1488-1576 • Born Tiziano Vecellio in Pieve di Cadrone – Small fortified town dating back to the Iron Age. • Father a soldier / local councilor / supplier of timber to Venice • Named after a local saint Titianus • Went to Venice aged 9, apprenticed to Zuccato then Gentile Bellini then Giovani Bellini • Partnership with Giorgione – shared workshop – ended with G’s early death • Together redefined Venetian painting • Their work so similar have long been disputes over authorship of some paintings They did undertake some joint works – frescoes Titian was asked to complete some unfinished works after Giorgione’s death – only one such is known for sure – otherwise we don’t know if he did finish others. The Pastoral Concert - Once considered Giorgione – now considered Titian – though some have considered as by both (Louvre). • Portraits - Royal and Papal commissions late in career • Cabinet Pictures • Religious art • Allegorical / Classical Isabella d’Este “La Bella” • Lead the movement to having large pictures for architectural locations on canvas rather than Fresco – which lasted poorly in Venice’s damp climate • Sought to displace his teacher Bellini as official state painter – declined, but achieved on B’s death. • Married housekeeper by whom he already has two children • Wife dies young in childbirth – a daughter modelled for him for his group pictures • Does not remarry – described as flirting with women but not interested in relationships • Ran a large studio – El Greco was one pupil • Of his most successful pictures many copies were made in the studio Penitent Mary Madelene Two of many versions Christ Carrying the Cross. -

Donato Bramante 1 Donato Bramante

Donato Bramante 1 Donato Bramante Donato Bramante Donato Bramante Birth name Donato di Pascuccio d'Antonio Born 1444Fermignano, Italy Died 11 April 1514 (Aged about 70)Rome Nationality Italian Field Architecture, Painting Movement High Renaissance Works San Pietro in Montorio Christ at the column Donato Bramante (1444 – 11 March 1514) was an Italian architect, who introduced the Early Renaissance style to Milan and the High Renaissance style to Rome, where his most famous design was St. Peter's Basilica. Urbino and Milan Bramante was born in Monte Asdrualdo (now Fermignano), under name Donato di Pascuccio d'Antonio, near Urbino: here, in 1467 Luciano Laurana was adding to the Palazzo Ducale an arcaded courtyard and other features that seemed to have the true ring of a reborn antiquity to Federico da Montefeltro's ducal palace. Bramante's architecture has eclipsed his painting skills: he knew the painters Melozzo da Forlì and Piero della Francesca well, who were interested in the rules of perspective and illusionistic features in Mantegna's painting. Around 1474, Bramante moved to Milan, a city with a deep Gothic architectural tradition, and built several churches in the new Antique style. The Duke, Ludovico Sforza, made him virtually his court architect, beginning in 1476, with commissions that culminated in the famous trompe-l'oeil choir of the church of Santa Maria presso San Satiro (1482–1486). Space was limited, and Bramante made a theatrical apse in bas-relief, combining the painterly arts of perspective with Roman details. There is an octagonal sacristy, surmounted by a dome. In Milan, Bramante also built the tribune of Santa Maria delle Grazie (1492–99); other early works include the cloisters of Sant'Ambrogio, Milan (1497–1498), and some other constructions in Pavia and possibly Legnano. -

Sebastiano Del Piombo and His Collaboration with Michelangelo: Distance and Proximity to the Divine in Catholic Reformation Rome

SEBASTIANO DEL PIOMBO AND HIS COLLABORATION WITH MICHELANGELO: DISTANCE AND PROXIMITY TO THE DIVINE IN CATHOLIC REFORMATION ROME by Marsha Libina A dissertation submitted to the Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland April, 2015 © 2015 Marsha Libina All Rights Reserved Abstract This dissertation is structured around seven paintings that mark decisive moments in Sebastiano del Piombo’s Roman career (1511-47) and his collaboration with Michelangelo. Scholarship on Sebastiano’s collaborative works with Michelangelo typically concentrates on the artists’ division of labor and explains the works as a reconciliation of Venetian colorito (coloring) and Tuscan disegno (design). Consequently, discourses of interregional rivalry, center and periphery, and the normativity of the Roman High Renaissance become the overriding terms in which Sebastiano’s work is discussed. What has been overlooked is Sebastiano’s own visual intelligence, his active rather than passive use of Michelangelo’s skills, and the novelty of his works, made in response to reform currents of the early sixteenth century. This study investigates the significance behind Sebastiano’s repeating, slowing down, and narrowing in on the figure of Christ in his Roman works. The dissertation begins by addressing Sebastiano’s use of Michelangelo’s drawings as catalysts for his own inventions, demonstrating his investment in collaboration and strategies of citation as tools for artistic image-making. Focusing on Sebastiano’s reinvention of his partner’s drawings, it then looks at the ways in which the artist engaged with the central debates of the Catholic Reformation – debates on the Church’s mediation of the divine, the role of the individual in the path to personal salvation, and the increasingly problematic distance between the layperson and God. -

Italian Humanism Was Developed During the Fourteenth and the Beginning of the Fifteenth Centuries As a Response to the Medieval Scholastic Education

Italian Humanism Was developed during the fourteenth and the beginning of the fifteenth centuries as a response to the Medieval scholastic education • Growing concern with the natural world, the individual, and humanity’s worldly existence. • Revived interest in classical cultures and attempt to restore the glorious past of Greece and Rome. Recovering of Greek and Roman texts that were previously lost or ignored. • Interest in the liberal arts - grammar, rhetoric, poetry, history and moral philosophy. • Promotes human values as distinct from religious values, mainly Roman civic virtues: self-sacrificing service to the state, participation in government, defense of state institutions. Renaissance architecture: Style of architecture, reflecting the rebirth of Classical culture, that originated in Florence in the early 15th century. There was a revival of ancient Roman forms, including the column and round arch, the tunnel vault, and the dome. The basic design element was the order. Knowledge of Classical architecture came from the ruins of ancient buildings and the writings of Vitruvius. As in the Classical period, proportion was the most important factor of beauty. Filippo Brunelleschi (1377 - 1446), Florentine architect and engineer. Trained as a sculptor and goldsmith, he turned his attention to architecture after failing to win a competition for the bronze doors of the Baptistery of Florence. Besides accomplishments in architecture, Brunelleschi is also credited with inventing one-point linear perspective which revolutionized painting. Sculpture of Brunelleschi looking at the dome in Florence Filippo Brunelleschi, Foundling Hospital, (children's orphanage that was built and managed by the Silk and Goldsmiths Guild), Florence, Italy, designed 1419, built 1421-44 Loggia Arcade A roofed arcade or gallery with open sides A series of arches supported by stretching along the front or side of a building. -

Raphael's School of Athens: a Theorem in a Painting?

Journal of Humanistic Mathematics Volume 2 | Issue 2 July 2012 Raphael's School of Athens: A Theorem in a Painting? Robert Haas Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, and the Geometry and Topology Commons Recommended Citation Haas, R. "Raphael's School of Athens: A Theorem in a Painting?," Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, Volume 2 Issue 2 (July 2012), pages 2-26. DOI: 10.5642/jhummath.201202.03 . Available at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/vol2/iss2/3 ©2012 by the authors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License. JHM is an open access bi-annual journal sponsored by the Claremont Center for the Mathematical Sciences and published by the Claremont Colleges Library | ISSN 2159-8118 | http://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/ The editorial staff of JHM works hard to make sure the scholarship disseminated in JHM is accurate and upholds professional ethical guidelines. However the views and opinions expressed in each published manuscript belong exclusively to the individual contributor(s). The publisher and the editors do not endorse or accept responsibility for them. See https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/policies.html for more information. Raphael's School of Athens: A Theorem in a Painting? Cover Page Footnote Acknowledgments: I thank Robert J. Kolesar, Professor of Mathematics at John Carroll University, and Jon L. Seydl, the Paul J. and Edith Ingalls Vignos, Jr., Curator of European Painting and Sculpture, 1500-1800, at the Cleveland Museum of Art, for their comments and encouragement on the manuscript. -

14 a Creative Process

CONTEMPORARY TOPICS II E-ISSN 2237 -2660 A Creative Process between Painting and Body Arts: Carolee Schneemann and Aby Warburg Vera Pugliese I IUniversidade de Brasília – UnB, Brasília/DF, Brazil ABSTRACT – A Creative Process between Painting and Body Arts: Carolee Schneemann and Aby Warburg 1,2 – This article discusses the issue of the pictorial gesture potency in Carolee Schneemann’s creating pro- cess and how her use of herself body allowed her to question whether she could, in addition to an image be also an image maker : a poetic and theoretical juxtaposition at the same time, which causes specific displacements in her per- formative work. This study aims to correlate operatory concepts around the nymph as a theoretical object, with spe- cial attention to its accessories in movement, in the Warburgian sense, from the examination of iconological paths and theoretical approaches inaugurated by Aby Warburg, having as focus the crossings between painting and the body arts. Keywords: Performance and Painting. Pathosformeln . Contemporary Poetics. Carolee Schneemann. Aby Warburg. RÉSUMÉ – Un Processus de Création entre la Peinture et les Arts du Corps: Carolee Schneemann et Aby Warburg – Cet article traite de la question de la puissance du geste pictural dans le processus de création de Carolee Schneemann et de la façon dont son utilisation du corps lui a permis de se demander si elle pouvait, en plus d’une image, être aussi une image maker : à la fois une juxtaposition poétique et théorique qui provoque des déplacements spécifiques dans son œuvre performatique. On cherche corréler les concepts opératoires autour de la nymphe en tant qu’objet théorique, avec une attention particulière à ses accessoires en mouvement , dans le sens warburgien à partir de l’examen des parcours iconologiques et les approches théoriques inaugurés par Aby Warburg, ayant comme accent les croisements entre la peinture et les arts du corps. -

Titian's Later Mythologies Author(S): W

Titian's Later Mythologies Author(s): W. R. Rearick Source: Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 17, No. 33 (1996), pp. 23-67 Published by: IRSA s.c. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1483551 . Accessed: 18/09/2011 17:13 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae. http://www.jstor.org W.R. REARICK Titian'sLater Mythologies I Worship of Venus (Madrid,Museo del Prado) in 1518-1519 when the great Assunta (Venice, Frari)was complete and in place. This Seen together, Titian's two major cycles of paintingsof mytho- was followed directlyby the Andrians (Madrid,Museo del Prado), logical subjects stand apart as one of the most significantand sem- and, after an interval, by the Bacchus and Ariadne (London, inal creations of the ItalianRenaissance. And yet, neither his earli- National Gallery) of 1522-1523.4 The sumptuous sensuality and er cycle nor the later series is without lingering problems that dynamic pictorial energy of these pictures dominated Bellini's continue to cloud their image as projected -

Boucher: Three Pastoral Scenes

Art Appreciation Lecture Series 2015 Meet the Masters: Highlights from the Scottish National Gallery Meet the Masters: Boucher: three pastoral scenes Lecturer: Professor Mark Ledbury, University of Sydney 10 & 11 June 2015 Lecture summary: This lecture explores the three Pastoral Scenes by François Boucher in the Scottish National Gallery , discussing the personal, institutional and generic contexts in which they were produced and understood and examining through them whether the oft-repeated criticisms of Boucher’s unnatural and unrealistic pastoral style were in fact a product of misunderstanding both of the genre and the complexity of the painter’s compositions. The Lecture will argue that Boucher’s enjoyment of both artifice and nature, and his unashamed love of painting as decoration, demonstrate not his moral debauchery and superficiality but his keen and essential grasp of the painter’s role and the possibilities of painting in the eighteenth century. Slide list: 1. Gustaf Lumberg, Portrait of François Boucher (1741, Pastel, Musée du Louvre, Paris) 2. François Boucher, Venus and Vulcan (1732, Oil on Canvas, Musée du Louvre, Paris) 3. François Boucher, Portrait of Madame Pompadour (1748, Oil on Canvas, Munich, Alte Pinakothek) 4. François Boucher, Odalisque , (c1745, Oil on Canvas, Paris: Louvre) 5. François Boucher, Study of a woman , (Chalk, Pencil on Paper, New York, Cooper Hewitt) 6. François Boucher, The Milliner (Morning) 1746 Oil on Canvas, , Stockholm, Nationalmuseum 7. François Boucher, Pastoral Scene (The offering to the Village Girl), c1762, Oil on Canvas, National Gallery of Scotland 8. François Boucher, Pastoral Scene (The Gallant or Aimiable Pastoral), c.1762, Oil on Canvas, National Gallery of Scotland 9. -

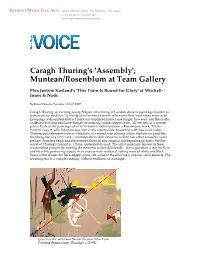

Caragh Thuring's 'Assembly'; Muntean/Rosenblum at Team Gallery

Caragh Thuring's 'Assembly'; Muntean/Rosenblum at Team Gallery Plus Justine Kurland's 'This Train Is Bound for Glory' at Mitchell- Innes & Nash By Daniel Kunitz Tuesday, Oct 27 2009 Caragh Thuring, an exciting young Belgian artist living in London, dissects paintings in order to reanimate the medium. At first glance, the five canvases in her first New York show seem to be groupings of disjointed abstract marks on unprimed linen. Look longer, however, and the marks coalesce, resolving into loose though structurally sound compositions, all versions of a country picnic. Each of the paintings takes as its source and inspiration a Renaissance work, Titian's Pastoral Concert, which depicts two men in the countryside disporting with two nude ladies. Thuring pulls elements from it—the form of a seated man playing a lute, the bow on a red hat, the tilting line of a tree trunk—combines them with elements culled from other artworks, some perhaps from her head, and reassembles them all into original and beguiling pictures. But the secret of Thuring's concert is, I think, controlled discord. The artist maintains tension in these reassembled pictures by treating the elements within differently—she might draw a tree trunk in outline while portraying a body in an expressively rendered, roiling mass of white and black. Some of the shapes are hard-edged, some soft; some of the drawing is precise, some gestural. The resulting mix is a complex melody without stuffiness or nostalgia. Courtesy the artist and Simon Preston New York Painting Renaissance: Thuring's 1 (2009) Details Caragh Thuring: 'Assembly' Simon Preston Gallery 301 Broome Street, 212-431-1105 Through November 1 Muntean/Rosenblum: 'Untitled '09' If, in recent years, we've not seen much good painterly painting like Thuring's, that's because the medium has been dominated by the sort of work done by the Viennese artist duo Muntean and Rosenblum: conceptually inclined, narrative-based, illustrational canvases.