“This Is Mud on Our Faces! We're Not Really Black!” Teaching Gender, Race

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses 5-2010 Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions Stephanie Savage Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, and the Marketing Commons Savage, Stephanie, "Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions" (2010). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 54. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/54 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Savage 1 “Who’s gonna turn down a Junior Mint? It’s chocolate, it’s peppermint ─it’s delicious!” While this may sound like your typical television commercial, you can thank Jerry Seinfeld and his butter fingers for what is actually one of the most renowned lines in television history. As part of a 1993 episode of Seinfeld , subsequently known as “The Junior Mint,” these infamous words have certainly gained a bit more attention than the show’s writers had originally bargained for. In fact, those of you who were annoyed by last year’s focus on a McDonald’s McFlurry on NBC’s 30 Rock may want to take up your beef with Seinfeld’s producers for supposedly showing marketers the way to the future ("Brand Practice: Product Integration Is as Old as Hollywood Itself"). -

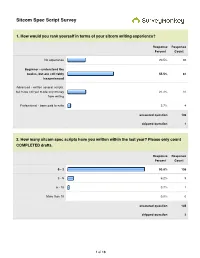

Sitcom Spec Script Survey

Sitcom Spec Script Survey 1. How would you rank yourself in terms of your sitcom writing experience? Response Response Percent Count No experience 20.5% 30 Beginner - understand the basics, but are still fairly 55.5% 81 inexperienced Advanced - written several scripts, but have not yet made any money 21.2% 31 from writing Professional - been paid to write 2.7% 4 answered question 146 skipped question 1 2. How many sitcom spec scripts have you written within the last year? Please only count COMPLETED drafts. Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 93.8% 136 3 - 5 6.2% 9 6 - 10 0.7% 1 More than 10 0.0% 0 answered question 145 skipped question 2 1 of 18 3. Please list the sitcoms that you've specced within the last year: Response Count 95 answered question 95 skipped question 52 4. How many sitcom spec scripts are you currently writing or plan to begin writing during 2011? Response Response Percent Count 0 - 2 64.5% 91 3 - 4 30.5% 43 5 - 6 5.0% 7 answered question 141 skipped question 6 5. Please list the sitcoms in which you are either currently speccing or plan to spec in 2011: Response Count 116 answered question 116 skipped question 31 2 of 18 6. List any sitcoms that you believe to be BAD shows to spec (i.e. over-specced, too old, no longevity, etc.): Response Count 93 answered question 93 skipped question 54 7. In your opinion, what show is the "hottest" sitcom to spec right now? Response Count 103 answered question 103 skipped question 44 8. -

Press Release Preview

HALLMARK CHANNEL’S ANNUAL CHRISTMAS IN JULY KICKS OFF, MAKING THE NETWORK #1 MOST-WATCHED ON SATURDAY AND IN WEEKEND TOTAL DAY Saturday Night Original Movie Premiere Crashing Through the Snow Becomes #1 Most-Watched Program of the Day NEW YORK – July 14, 2021 –Hallmark Channel’s 2021 Christmas in July programming event kicked off on Friday, making the network the #1 most-watched during Weekend Total Day among Households and Women 18+. The Saturday night original holiday movie premiere Crashing Through the Snowaveraged 2.0 million Total Viewers becoming the #1 most- watched entertainment cable program of the week among Households and Women 18+. Key Nielsen Highlights (L+SD) Crashing Through the Snow averaged 1.7 million Homes, 216K Women 25-54, and 2.0 million Total Viewers, and reached 2.8 million unduplicated Total Viewers The film propelled Hallmark Channel to become the #1 most-watched entertainment cable network on Saturday and in Weekend Total Day among Households and Women 18+ Crashing Through the Snow was the #1 most-watched entertainment cable program of the week among Households and Women 18+ Additionally, Hallmark Channel became the #2 most-watched entertainment network in Total Day for the week among Households, Women 18+, and Total Viewers Source: Nielsen L+SD 7/5/21-7/11/21; Excluding news and sports; Unduplicated P2+ audience, 6 min qualifier. Contact: Sakina Howard | 917-208-6302| [email protected] ABOUT HALLMARK CHANNEL Hallmark Channel, owned by Hallmark Cards, Inc., is Crown Media Family Networks’ flagship 24-hour cable television network. As the country’s leading destination for quality family entertainment, Hallmark Channel delivers on the 100-year legacy of the Hallmark brand. -

72Nd Emmy's Nominations Facts Figures

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2020 NOMINATIONS as of July 28, 2020 does not include producer nominations 72nd EMMY AWARDS updated 07.28.2020 version 1 Page 1 of 24 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2019 Game Of Thrones - 12 Chernobyl - 10 The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel - 8 Free Solo – 7 Fleabag - 6 Love, Death & Robots - 5 Saturday Night Live – 5 Fosse/Verdon – 4 Last Week Tonight With John Oliver – 4 Queer Eye - 4 RuPaul’s Drag Race - 4 Age Of Sail - 3 Barry - 3 Russian Doll - 3 State Of The Union – 3 The Handmaid’s Tale – 3 Anthony Bourdain Parts Unknown – 2 Bandersnatch (Black Mirror) - 2 Crazy Ex-Girlfriend – 2 Our Planet – 2 Ozark – 2 RENT – 2 Succession - 2 United Shades Of America With W. Kamau Bell – 2 When They See Us – 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2019 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Fleabag Drama Series: Game Of Thrones Limited Series: Chernobyl Television Movie: Bandersnatch (Black Mirror) Reality-Competition Program: RuPaul’s Drag Race Variety Series (Talk): Last Week Tonight With John Oliver Variety Series (Sketch): Saturday Night Live PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Phoebe Waller-Bridge (Fleabag) Lead Actor: Bill Hader (Barry) Supporting Actress: Alex Borstein (The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel) Supporting Actor: Tony Shalhoub (The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Jodie Comer (Killing Eve) Lead Actor: Billy Porter (Pose) Supporting Actress: Julia Garner (Ozark) Supporting Actor: Peter Dinklage (Game Of Thrones) Limited Series/Movie: Lead Actress: Michelle Williams (Fosse/Verdon) Lead Actor: Jharrel Jerome (When They See Us) Supporting -

“You're the Worst Gay Husband Ever!” Progress and Concession in Gay

Title P “You’re the Worst Gay Husband ever!” Progress and Concession in Gay Sitcom Representation A thesis presented by Alex Assaf To The Department of Communications Studies at the University of Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Honors) April 2012 Advisors: Prof. Shazia Iftkhar Prof. Nicholas Valentino ii Copyright ©Alex Assaf 2012 All Rights Reserved iii Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my Nana who has always motivated me to pursue my interests, and has served as one of the most inspirational figures in my life both personally and academically. iv Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank my incredible advisors Professor Shazia Iftkhar and Professor Nicholas Valentino for reading numerous drafts and keeping me on track (or better yet avoiding a nervous breakdown) over the past eight months. Additionally, I’d like to thank my parents and my friends for putting up with my incessant mentioning of how much work I always had to do when writing this thesis. Their patience and understanding was tremendous and helped motivate me to continue on at times when I felt uninspired. And lastly, I’d like to thank my brother for always calling me back whenever I needed help eloquently naming all the concepts and patterns that I could only describe in my head. Having a trusted ally to bounce ideas off and to help better express my observations was invaluable. Thanks, bro! v Abstract This research analyzes the implicit and explicit messages viewers receive about the LGBT community in primetime sitcoms. -

30 Rock and Philosophy: We Want to Go to There (The Blackwell

ftoc.indd viii 6/5/10 10:15:56 AM 30 ROCK AND PHILOSOPHY ffirs.indd i 6/5/10 10:15:35 AM The Blackwell Philosophy and Pop Culture Series Series Editor: William Irwin South Park and Philosophy X-Men and Philosophy Edited by Robert Arp Edited by Rebecca Housel and J. Jeremy Wisnewski Metallica and Philosophy Edited by William Irwin Terminator and Philosophy Edited by Richard Brown and Family Guy and Philosophy Kevin Decker Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Heroes and Philosophy The Daily Show and Philosophy Edited by David Kyle Johnson Edited by Jason Holt Twilight and Philosophy Lost and Philosophy Edited by Rebecca Housel and Edited by Sharon Kaye J. Jeremy Wisnewski 24 and Philosophy Final Fantasy and Philosophy Edited by Richard Davis, Jennifer Edited by Jason P. Blahuta and Hart Weed, and Ronald Weed Michel S. Beaulieu Battlestar Galactica and Iron Man and Philosophy Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White Edited by Jason T. Eberl Alice in Wonderland and The Offi ce and Philosophy Philosophy Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Edited by Richard Brian Davis Batman and Philosophy True Blood and Philosophy Edited by Mark D. White and Edited by George Dunn and Robert Arp Rebecca Housel House and Philosophy Mad Men and Philosophy Edited by Henry Jacoby Edited by Rod Carveth and Watchman and Philosophy James South Edited by Mark D. White ffirs.indd ii 6/5/10 10:15:36 AM 30 ROCK AND PHILOSOPHY WE WANT TO GO TO THERE Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ffirs.indd iii 6/5/10 10:15:36 AM To pages everywhere . -

Modern Family"

Representation of Gender in "Modern Family" Vuković, Tamara Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2016 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zadar / Sveučilište u Zadru Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:162:639538 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-26 Repository / Repozitorij: University of Zadar Institutional Repository of evaluation works Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Diplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti; smjer: nastavnički (dvopredmetni) Tamara Vuković Representation of Gender in “Modern Family” Diplomski rad Zadar, 2016. Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Diplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti; smjer: nastavnički (dvopredmetni) Representation of Gender in “Modern Family” Diplomski rad Student/ica: Mentor/ica: Tamara Vuković izv. prof. dr. sc. Senka Božić-Vrbančić Zadar, 2016. Izjava o akademskoj čestitosti Ja, Tamara Vuković, ovime izjavljujem da je moj diplomski rad pod naslovom Representation of Gender in „Modern Family“ rezultat mojega vlastitog rada, da se temelji na mojim istraživanjima te da se oslanja na izvore i radove navedene u bilješkama i popisu literature. Ni jedan dio mojega rada nije napisan na nedopušten način, odnosno nije prepisan iz necitiranih radova i ne krši bilo čija autorska prava. Izjavljujem da ni jedan dio ovoga rada nije iskorišten u kojem drugom radu pri bilo kojoj drugoj visokoškolskoj, znanstvenoj, obrazovnoj ili inoj ustanovi. Sadržaj -

From the Golden Girls to Grace and Frankie ………………………………………………………………………………………………………

HyperCultura Biannual Journal of the Department of Letters and Foreign Languages, Hyperion University, Romania Electronic ISSN: 2559 – 2025; ISSN-L 2285 – 2115 OPEN ACCESS Vol 7/ 201 8 Issue Editor: Sorina Georgescu ....................................................................................................... Rocío Palomeque Recio Sex Toys for Women with Arthritis: From the Golden Girls to Grace and Frankie ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Recommended Citation: Recio, Rocío Palomeque. “Sex Toys for Women with Arthritis: From the Golden Girls to Grace and Frankie .” HyperCultura 7 (2018) ……………………………………………………………………………………………………….. http://litere.hyperion.ro/hypercultura/ License: CC BY 4.0 Received: 30 August 2018/ Accepted: 18 February 2019/ Published: 31 March 2019 No conflict of interest Rocío Palomeque Recio, “Sex Toys for Women with Arthritis: From the Golden Girls to Grace and Frankie.” Rocío Palomeque Recio Nottingham Trent University Sex Toys for Women with Arthritis: From the Golden Girls to Grace and Frankie Abstract: The purpose of this work is to perform a comparative analysis of how women’s sexuality is displayed in both the American TV show Grace and Frankie (2015-present) and The Golden Girls (1985-1992) using a post- feminist optic (Genz and Brabon 2018). The post-feminist rhetoric, which surged as a result of the economic boom of the 1990s and 2000s, optimistically embraces consumer freedom, choice and empowerment (Genz and Brabon 2018) and presents women as assertive beings who enjoy their sexual freedom and financial agency. Analyzing two shows that feature senior women as their main characters , whose pilot episodes aired thirty years apart can shed some light on how media have changed the portrayal of senior women and their sexualities. The Golden Girls and Grace and Frankie share enough features to enable us to trace similarities: the leading characters are all white women, middle-upper class American, for instance. -

Resistance to Hegemonic Masculinity in Modern Family

Journal of Contemporary Rhetoric, Vol. 11, No.1/2, 2021, pp. 36-56. Modern Masculinities: Resistance to Hegemonic Masculinity in Modern Family Jennifer Y. Abbott∗ Cory Geraths+ Since its debut in 2009, the ABC television show Modern Family has captivated audiences and academics alike. The show professes a modern perspective on families, but many scholars have concluded that its male characters uphold problematic, normative expressions of gender. In contrast, we use the concept of hegemonic masculinity to argue that Modern Family resists normative expressions of masculinity by attuning viewers to the socially constructed nature of hegemonic masculinity and by authorizing feminine and flamboyant behaviors as appropriately manly. These coun- terhegemonic strategies work in tandem to scrutinize confining expectations for men and to offer viable alternatives. Taken together, their coexistence mitigates against an oppressive hybrid version of hegemonic masculinity. Conse- quently, our analysis introduces readers to the rhetorical power of hegemonic masculinity and strategies to resist it; considers the efficacy of these strategies while drawing a wide audience; and stresses the importance of diverse gender representation in popular media. Keywords: Modern Family, hegemonic masculinity, resistance, comedy, television, sitcom The ABC television show Modern Family concluded on April 8, 2020, securing its place in history as among the longest running and most successful domestic situation comedies. Beginning with its first season in 2009, and ending with its eleventh and final season in 2020, the series currently stands as the “third longest-running network sitcom in television history.”1 While ratings dipped ∗ Jennifer Y. Abbott (Ph.D., The Pennsylvania State University) is a Professor of Rhetoric at Wabash College and is affiliated with the college’s Gender Studies program. -

Representation of Jews in the Media: an Analysis of Old Hollywood Stereotypes Perpetuated in Modern Television Minnah Marguerite Stein

)ORULGD6WDWH8QLYHUVLW\/LEUDULHV 2021 Representation of Jews in the Media: An Analysis of Old Hollywood Stereotypes Perpetuated in Modern Television Minnah Marguerite Stein Follow this and additional works at DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATIONS REPRESENTATION OF JEWS IN THE MEDIA: AN ANALYSIS OF OLD HOLLYWOOD STEREOTYPES PERPETUATED IN MODERN TELEVISION By MINNAH STEIN A Thesis submitted to the Department of Communications and Media Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with Honors in the Major Degree Awarded: Summer, 2021 The members of the Defense Committee approve the thesis of Minnah Stein defended on April 2, 2021. Dr. Andrew Opel Thesis Director Dr. Martin Kavka Outside Committee Member Dr. Arienne Ferchaud Committee Member 2 Abstract Anti-Semitism in the United States is just as prevalent today as it has ever been. How does this cultural anti-Semitism translate into the media? Through portraying Jews as greedy, neurotic, pushy, money obsessed, cheap, and a myriad other negative stereotypes, the media often perpetuates long standing anti-Semitic tropes. This thesis analyzes the prevalence of Jewish stereotypes in modern television through the analysis and discussion of three of the most popular current television shows, getting into the nuance and complexity of Jewish representation. Through the deliberate viewing of Big Mouth, The Goldbergs, and Schitt’s Creek, the conclusion is that although an effort is being made to debunk some stereotypes about Jews, there are other Jewish stereotypes that have remained popular in television media. These stereotypes are harmful to Jews because they both feed and fuel the anti-Semitic attitudes of viewers. -

Rank Series T Title N Network Wr Riter(S)*

Rank Series Title Network Writer(s)* 1 The Sopranos HBO Created by David Chase 2 Seinfeld NBC Created by Larry David & Jerry Seinfeld The Twilighht Zone Season One writers: Charles Beaumont, Richard 3 CBS (1959)9 Matheson, Robert Presnell, Jr., Rod Serling Developed for Television by Norman Lear, Based on Till 4 All in the Family CBS Death Do Us Part, Created by Johnny Speight 5 M*A*S*H CBS Developed for Television by Larry Gelbart The Mary Tyler 6 CBS Created by James L. Brooks and Allan Burns Moore Show 7 Mad Men AMC Created by Matthew Weiner Created by Glen Charles & Les Charles and James 8 Cheers NBC Burrows 9 The Wire HBO Created by David Simon 10 The West Wing NBC Created by Aaron Sorkin Created by Matt Groening, Developed by James L. 11 The Simpsons FOX Brooks and Matt Groening and Sam Simon “Pilot,” Written by Jess Oppenheimer & Madelyn Pugh & 12 I Love Lucy CBS Bob Carroll, Jrr. 13 Breaking Bad AMC Created by Vinnce Gilligan The Dick Van Dyke 14 CBS Created by Carl Reiner Show 15 Hill Street Blues NBC Created by Miichael Kozoll and Steven Bochco Arrested 16 FOX Created by Miitchell Hurwitz Development Created by Madeleine Smithberg, Lizz Winstead; Season One – Head Writer: Chris Kreski; Writers: Jim Earl, Daniel The Daily Show with COMEDY 17 J. Goor, Charlles Grandy, J.R. Havlan, Tom Johnson, Jon Stewart CENTRAL Kent Jones, Paul Mercurio, Guy Nicolucci, Steve Rosenfield, Jon Stewart 18 Six Feet Under HBO Created by Alan Ball Created by James L. Brooks and Stan Daniels and David 19 Taxi ABC Davis and Ed Weinberger The Larry Sanders 20 HBO Created by Garry Shandling & Dennis Klein Show 21 30 Rock NBC Created by Tina Fey Developed for Television by Peter Berg, Inspired by the 22 Friday Night Lights NBC Book by H.G.