Responding to Requests for Information on Health Systems From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Singapore, July 2006

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Singapore, July 2006 COUNTRY PROFILE: SINGAPORE July 2006 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Singapore (English-language name). Also, in other official languages: Republik Singapura (Malay), Xinjiapo Gongheguo― 新加坡共和国 (Chinese), and Cingkappãr Kudiyarasu (Tamil) சி க யரச. Short Form: Singapore. Click to Enlarge Image Term for Citizen(s): Singaporean(s). Capital: Singapore. Major Cities: Singapore is a city-state. The city of Singapore is located on the south-central coast of the island of Singapore, but urbanization has taken over most of the territory of the island. Date of Independence: August 31, 1963, from Britain; August 9, 1965, from the Federation of Malaysia. National Public Holidays: New Year’s Day (January 1); Lunar New Year (movable date in January or February); Hari Raya Haji (Feast of the Sacrifice, movable date in February); Good Friday (movable date in March or April); Labour Day (May 1); Vesak Day (June 2); National Day or Independence Day (August 9); Deepavali (movable date in November); Hari Raya Puasa (end of Ramadan, movable date according to the Islamic lunar calendar); and Christmas (December 25). Flag: Two equal horizontal bands of red (top) and white; a vertical white crescent (closed portion toward the hoist side), partially enclosing five white-point stars arranged in a circle, positioned near the hoist side of the red band. The red band symbolizes universal brotherhood and the equality of men; the white band, purity and virtue. The crescent moon represents Click to Enlarge Image a young nation on the rise, while the five stars stand for the ideals of democracy, peace, progress, justice, and equality. -

Caring for Our People: 50 Years of Healthcare in Singapore

Caring for our People Prime Minister’s Message Good health is important for individuals, for families, and for our society. It is the foundation for our people’s vitality and optimism, and a reflection of our nation’s prosperity and success. A healthy community is also a happy one. Singapore has developed our own system for providing quality healthcare to all. Learning from other countries and taking advantage of a young population, we invested in preventive health, new healthcare facilities and developing our healthcare workforce. We designed a unique financing system, where individuals receive state subsidies for public healthcare but at the same time can draw upon the 3Ms – Medisave, MediShield and Medifund – to pay for their healthcare needs. As responsible members of society, each of us has to save for our own healthcare needs, pay our share of the cost, and make good and sensible decisions about using healthcare services. Our healthcare outcomes are among the best in the world. Average life expectancy is now 83 years, compared with 65 years in 1965. The infant mortality rate is 2 per 1,000 live births, down from 26 per 1,000 live births 50 years ago. This book is dedicated to all those in the Government policies have adapted to the times. We started by focusing on sanitation and public health and went on healthcare sector who laid the foundations to develop primary, secondary and tertiary health services. In recent years, we have enhanced government subsidies of a healthy nation in the years gone by, substantially to ensure that healthcare remains affordable. -

Health and Medical Research in Singapore Observatory on Health Research Systems

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Europe View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation documented briefing series. RAND documented briefings are based on research briefed to a client, sponsor, or targeted au- dience and provide additional information -

รายงานวิจัยฉบับสมบูรณ ASEAN Tourism Image Positioning: the Case Study of Singapore

รายงานวจิ ัยฉบับสมบูรณ ASEAN Tourism Image Positioning: The Case Study of Singapore โดย วลัยพร ริ้วตระกูลไพบูลย ตุลาคม 2552 สัญญาเลขท ี่ ABTC/ATR/00001 รายงานวจิ ัยฉบับสมบูรณ ASEAN Tourism Image Positioning: The Case Study of Singapore ผูวิจัย สังกัด วลัยพร รวตระกิ้ ูลไพบูลย มหาวิทยาลัยกรุงเทพ ชุดโครงการ ASEAN Tourism Image Positioning สนับสนุนโดย สํานักงานสนับสนุนการวิจัย (ความคิดเหนในรายงานน็ ี้เปนของผูวจิ ัย สกว.ไมจ าเปํ นตองเหนด็ วยเสมอไป) ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to firstly thank Thailand Research Fund (TRF) for the grant to conduct this study and Dr.Therdchai Choibamroong for his assistance in the research process. Special thanks to Robert Khoo and Gladys Cheng of National Association of Travel Agents Singapore (NATAS), Junice Yeo and Edward Kwok of Singapore Tourism Board (STB) for their wonderful support for the data collection. My thanks also extend to my husband for his understanding and continued support for this research in several ways. Walaiporn Rewtrakunphaiboon, Ph.D. iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Tourism is one of ASEAN's most important and dynamic industries. The number of tourist arrivals in ASEAN has grown rapidly from 20 millions in 1991 to 51 millions in 2005. Since tourists become more experienced and the tourism industry itself has been highly competitive, international tourism therefore presents various opportunities and challenges to the region. The research problem of this study concerns ways to help ASEAN tourist destinations to position image to the changing needs and demand of tourists. This strategy will help increasing the number of tourist arrivals to the region by attracting both new tourists and repeat tourists. This study focuses particularly on Singapore tourism as part of several studies for image positioning for all ASEAN country members. -

Human Security and Health in Singapore: Going Beyond a Fortress Mentality

Human Security and Health in Singapore: Going Beyond a Fortress Mentality Lee Koh and Simon Barraclough Singapore has achieved high levels of human security, overcoming the socio- economic instability and poverty of its early days of independence in the mid 1960s. It is now a high-income, technologically advanced nation, providing its population with access to housing, healthcare and education. High standards of healthcare and positive indicators attest to population health security, despite the crisis of the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) pandemic. Despite this enviable position, Singapore has not been noted for regional and global engagement with human security and human rights, although this insular outlook is beginning to change. It is argued here that Singapore, as an emerging international “health hub”, scientific and educational center, has both the capacity and motivation to play a greater role in supporting health security, both regionally and globally. INTRODUCTION The 2003 Report on Human Security defines human security as the protection of “the vital core of all human lives in ways that enhance freedoms and human fulfilment”1. The Human Development Report (HDR) defined such security as “freedom from fear and freedom from want” 2, and pictured human security as “a child who did not die, a disease that did not spread, a job that was not cut, an ethnic tension that did not explode in violence, a dissident that was not silenced” 3. Human security faces various threats, which may include such ills as chronic destitution, violent conflicts, financial crises and terrorist attacks4. To these may be added menaces to one of the essentials of human security: health. -

Health Systems Reforms in Singapore: a Qualitative Study of Key Stakeholders

Accepted Manuscript Title: Health Systems Reforms in Singapore: A Qualitative Study of Key Stakeholders Authors: Suan Ee Ong, Shilpa Tyagi, Mingjie Jane Lim, Seng Kee Chia, Helena Legido-Quigley PII: S0168-8510(18)30048-4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.02.005 Reference: HEAP 3862 To appear in: Health Policy Received date: 28-4-2017 Revised date: 11-1-2018 Accepted date: 10-2-2018 Please cite this article as: Ong Suan Ee, Tyagi Shilpa, Lim Mingjie Jane, Chia Seng Kee, Legido-Quigley Helena.Health Systems Reforms in Singapore: A Qualitative Study of Key Stakeholders.Health Policy https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.02.005 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. Revisions: 11 January 2018 HEALTH SYSTEMS REFORMS IN SINGAPORE: A QUALITATIVE STUDY OF KEY STAKEHOLDERS Suan Ee ONG1, Shilpa TYAGI1, Jane Mingjie LIM1, Kee Seng CHIA1, Helena LEGIDO-QUIGLEY1,2 1Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore, Singapore 2London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, United Kingdom Corresponding Author Dr Helena Legido-Quigley Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health National University of Singapore 12 Science Drive 2, #10‐03H Tahir Foundation Building Singapore 117549 E: [email protected] HIGHLIGHTS The RHS is a national-level move towards caring for the patient holistically across the care continuum. -

A Study of Older Adults' Perception of High-Density Housing Neighbourhoods in Singapore: Multi-Sensory Perspective

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article A Study of Older Adults’ Perception of High-Density Housing Neighbourhoods in Singapore: Multi-Sensory Perspective Zdravko Trivic Department of Architecture, School of Design and Environment, National University of Singapore, Singapore 117566, Singapore; [email protected] Abstract: Associated sensory and cognitive declines progress with ageing and profoundly impact the daily living and quality of life of older adults. In the context of an increased ageing population globally, this paper outlines an exploratory study of socio-sensory properties of two high-density housing neighbourhoods in Singapore and the ways senior local residents perceive their familiar built environments. This study employed exploratory on-site exercises with 44 student researchers (including sensory photo-journeys, documentation of sensory properties and daily activity patterns), and 301 socio-perceptual surveys with local residents, the majority of whom were older adults. The findings reveal important aspects related to sensory assessment and appreciation (e.g., crowdedness, noise, smell, cleanliness), walking experience (e.g., safety, wayfinding) and overall satisfaction with the neighbourhood (e.g., available public amenities, opportunities for inter-generational bonding), some of which correlated with age and reported health condition. Multi-sensory assessment shows the capacity to inform more integrated, empathetic, ability-building and context-specific ageing- Citation: Trivic, Z. A Study of Older friendly neighbourhood design. Adults’ Perception of High-Density Housing Neighbourhoods in Keywords: age-friendly neighbourhood; multi-sensory experience; perception; ageing population; Singapore: Multi-Sensory Perspective. high-density environment Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6880. https://doi.org/10.3390/ ijerph18136880 1. -

Women's Heart Health in Singapore: a Culture-Centered Framework

CARE WHITE PAPER SERIES 2013 VOL. 1 Women’s Heart Health in Singapore: A Culture-Centered Framework Sarah K. Comer & Mohan J. Dutta THE CARE WHITE PAPER SERIES IS A PUBLICATION OF THE CENTER FOR CULTURE-CENTERED APPROACH TO RESEARCH AND EVALUATION (CARE), NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE Requests for permission to reproduce the CARE White Paper Series should be directed to the Department of Communications and New Media, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, National University of Singapore. DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATIONS AND NEW MEDIA CARE WHITE PAPER SERIES 11 Computing Drive, AS6 Level 3 National University of Singapore Singapore 117416 T (65)6516-4971 W http://www.fas.nus.edu.sg/cnm Women’s Heart Health Mohan J. Dutta, Head [email protected] in Singapore: A Culture-Centered Framework Copyright of this paper resides with the author(s) and further publication, in whole or in part, shall only be made by authorization of the author(s). Sarah K. Comer & Mohan J. Dutta Design, layout, and editing: Daniel Teo, CARE Research Assistant CARE is online at http://www.care-cca.com. CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE (CVD) is the Stampfer, Hu, Manson, Rimm, & Willett, ABOUT CARE leading cause of death globally (Bonow, 2000), diet (Heidemann et. al, 2008; Funded by a $1.9 million grant from the the problems conceptualized by them. Smaha, Smith, Mensah, & Lenfant, Odegaard, Koh, Gross, Yuan, & Pereira, National University of Singapore (NUS), 2002; Bonow, Smaha, Smith, Mensah, & 2011; Rankin & Bhopal, 2001), and CARE seeks to: (a) create a strategic CARE is a global -

The Orchid and the Singaporean Identity. Jonathan Alperstein Vassar College

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2018 Commodity, conservation, and nation building: the orchid and the Singaporean identity. Jonathan Alperstein Vassar College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Alperstein, Jonathan, "Commodity, conservation, and nation building: the orchid and the Singaporean identity." (2018). Senior Capstone Projects. 733. https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone/733 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Commodity, Conservation, and Nation Building: The Orchid and the Singaporean Identity. By Jonathan Alperstein BA thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, NY Thesis Readers: Xiaobo Yuan, Post-Doctoral Fellow and Luis Philippe Römer, Visiting Assistant Professor May 2018 Alperstein 2 Chapter 1: The Growth of a Nation and its Orchids A miniscule seed difficult to see by the naked eye is thrust into a small flask of sterile agar gel, with a swirl of necessary nutrients. The flask is thrown on to a large centrifuge, spun to allow the tiny seed to begin to germinate. The seed after some time will soon erupt, revealing a small, two-leaved plant. Kept in the confines of its personal sterile green house, the plant uses photosynthesis to achieve a more mature form. Eventually the plant will be moved to a larger flask until it is large enough to be de-flasked. The young plant will be brought out of artificial light to its new home: a small medicine-cup-sized plastic pot. -

Apr–Jun 2018 (PDF)

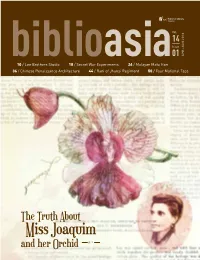

Vol. 14 Issue biblioasia01 APR–JUN 2018 10 / Lee Brothers Studio 18 / Secret War Experiments 24 / Malayan Mata Hari 36 / Chinese Renaissance Architecture 44 / Rani of Jhansi Regiment 50 / Four National Taps The Truth About Miss Joaquim and her Orchid p. 2 BiblioAsia Director’s Note Editorial & CONTENTS Vol. 14 / Issue 01 APR–JUN 2018 Production The proliferation of fake news isn’t a recent phenomenon. Fictitious accounts of how Agnes Managing Editor Joaquim stumbled upon her namesake orchid in her garden began circulating several Francis Dorai decades after she was credited for creating the hybrid by crossing two orchid species. FEATURE Writers Nadia Wright, Linda Locke and Harold Johnson separate fact from fiction in their Editor search for the truth. Veronica Chee Blooming Lies: The Vanda Similarly, not enough people know that Singapore was a base for nefarious experi- 02 Miss Joaquim Story Editorial Support ments in biological warfare during the Japanese Occupation. Between 1942 and 1945, a Masamah Ahmad laboratory was set up to breed bubonic plague-infected fleas and other deadly pathogens Jocelyn Lau Portraits from the for use as biological weapons. Cheong Suk-Wai finds out more from Singaporean war 10 Lee Brothers Studio history researcher Lim Shao Bin. Design and Print Oxygen Studio Designs Covert operations is also the subject of Ronnie Tan’s essay, as he recounts the fascinat- Pte Ltd Secret War Experiments ing story of Lee Meng, a Malayan Communist Party agent who headed its network of secret 18 in Singapore 02 10 18 couriers during the Emergency and the elaborate efforts hatched to trap her. -

Market Study Opportunities for the Dutch Life Sciences & Health Sector

Market Study: Opportunities for the Dutch Life Sciences & Health sector in Singapore Commissioned by the Netherlands Enterprise Agency SINGAPORE Market Study Opportunities for the Dutch Life Sciences & Health sector in Singapore PREFACE May 2019 Singapore’s high quality and affordable health system is a global healthcare frontrunner. The country has one of the highest (healthy) life expectancies in the world, but is also ageing rapidly. In 2030, the percentage of the population above 65 years old will have doubled. Together with an increasing burden of non- communicable (chronic) diseases, this creates a shift and sharp increase in health demands, putting pressure on Singapore’s health system. The ‘3 Beyonds-Policy’ has been designed by the Ministry of Health of Singapore to keep healthcare both good and affordable into the future. It focuses on improved prevention (Beyond Healthcare to Health), avoiding frequent hospital admissions by appropriate care at the community-level or at home (Beyond Hospital to Community), and improved focus on cost-effectiveness (Beyond Quality to Value). Singapore’s decision-makers in healthcare have an open approach to achieve the 3 Beyonds-plan by proactively studying international health systems, such as that in the Netherlands, and welcome foreign expert organisations to test and apply solutions for Singapore’s healthcare challenges within the country. Singapore functions as an entry point for the broader ASEAN market. Solutions which work in the Singaporean health system are picked up by other countries in the region. The country furthermore has an excellent business climate. This report was commissioned by the Netherlands Enterprise Agency (RVO.nl) and is produced by the Task Force Health Care (TFHC) in cooperation with the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Singapore. -

Affordable Excellence: the Singapore Healthcare Story

HASE LTIN This is the story of the Singapore healthcare system: how it works, how it is financed, its history, where it is going, and E what lessons it may hold for national health systems around the world. Singapore ranks sixth in the world in healthcare out- AFFORDABLE comes, yet spends proportionally less on healthcare than any other high-income country. This is the first book to set out a comprehensive system-level description of healthcare in Singapore, with a view to understanding what can be learned from its unique system design and development path. EXC ELLE The lessons from Singapore will be of interest to those currently Affordable planning the future of healthcare in emerging economies, as NC E: THE SINGAPORE HEA E: THE SINGAPORE Excellence well as those engaged in the urgent debates on healthcare in The Singapore Healthcare Story the wealthier countries faced with serious long-term challenges in healthcare financing. Policymakers, legislators, public health by William A. Haseltine officials responsible for healthcare systems planning, finance and operations, as well as those working on healthcare issues in universities and think tanks should understand how the Singa- pore system works to achieve affordable excellence. WILLIAM A. HASELTINE is President and Founder of LT HCARE S ACCESS Health International dedicated to promoting access to high-quality affordable healthcare worldwide, and is President of the William A. Haseltine Foundation for Medical Sciences TORY and the Arts. He was a Professor at Harvard Medical School and was the Founder and CEO of Human Genome Sciences. BROOKINGS Brookings Institution Press Washington, D.C.