D:011011-Operation Merccury.Rtf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chania : Explore & Experience

INDEX INDEX .......................................................................................................................................... 1 THE BYZANTINE WALL OF CHANIA ............................................................................................. 3 THE EGYPTIAN LIGHTHOUSE ...................................................................................................... 4 GIALI TZAMISI ............................................................................................................................. 5 VENETIAN NEORIA ...................................................................................................................... 6 FIRKA FORTRESS ......................................................................................................................... 7 CENTER OF MEDITERRANEAN ARCHITECTURE (GRAND ARSENAL)............................................ 8 ANCIENT KYDONIA (PROTO-MINOAN SETTLEMENT OF KASTELI) .............................................. 9 ANCIENT APTERA ......................................................................................................................10 ENTRANCE OF THE RENIER MANSION ......................................................................................11 GATE AND RAMPART SABBIONARA .........................................................................................12 THE MINARET OF AGIOS NIKOLAOS .........................................................................................13 THE GRAVES OF VENIZELOS FAMILY ........................................................................................14 -

Full Page Photo

GEOLOGICA BALCANICA, 27.1-2, Sofia, August. 1997, p. 91-100 Depositional processes in outer arc marginal sub-basins during the Messinian time; Messinian crisis: An example from western Crete Island, Greece Nikolaos Kontopoulos, Abraham Zelilidis University qf Patras, Department of Geology. 26110 Parras, Greece Fax (30) 6/-99/-900; E-mail [email protected] (Submitted: March 22, 1996; accepted for publication: April 3, 1996) HuKoAaoc KoHmonyAoc, A6paxaM JeAuAuouc - llpo Abstract: The ratio of sea-level falling rate to subsidence/ Lieccbl OCOOKOHaKOnAeHU.R 60 6HeUJHeOyl06blX Kpae6blX uplift rate was the master factor controlling the evolution MeccuHCKUX cy66accetiHax; MeccuHcKuti Kpu3uc: llpu of three adjacent marginal sub-basins, the Platanos, Kas Mep c JanaOHOcol.leHmpaAbHOlOKpuma, rpet~U.R. OTuo telli and Maleme Sub-Basins. During the Messinian, the weHHe CKopocrH noHHlKeHHJI ypooull MOPll K cKopocru Platanos Sub-Basin was characterized by a constant shelf onycKaHHll/nO.UHliTHll 6blJIO rJiaBHbiM $aKTOpOM, KOH environment with a water depth of deposition not more TpOJIHpyK>IUHM 3BOJIIOUHIO Tpex npHJielKall{HX KpaeBLIX than 50 m; a sabkha environment which changed during cy66acceiiHOB - nnaTaHOCKoro, KacTeJIHHCKOro H the latest Messinian to a shelf environment characterized ManeMCKOrO. 8 MeCCHHCKOe BpeMll nnaTaHOCKHH the Kastelli Basin, representing a water depth of deposition cy66acCCHH xapaKTepH30BaJICll yCTOH'IHBbiMH WeJlbt}>o changing from 0 m to less than SO m; fmally, a terrestrial BbiMH ycJIOBHliMH C rny6HHOH OC8.llKOHaKOMeRHll He environment which changed during ~he latest Messinian 6onee SO m: ca6xoBbiMH ycnoBHliMH, nepewe.umHMH B to a shallow marine environment, characterized the weJib$OBYIO 06CT8HOBKY B CaMOM I103,llHeM MeCCHHC, Maleme Basin, representing a sea-level rise of no more xapaKTepuJoaancll KacrenuiicKuii 6acceiiu, o6na,nal0ll{HH than 50 m. -

01 Hst 1-3 Nieuw.Indd 1 15-10-19 16:15 01 Hst 1-3 Nieuw.Indd 2 15-10-19 16:15 Hitlers Parachutistengeneraal Kurt Student (1890-1978): Een Militaire Biografie

Hitlers parachutistengeneraal 01 hst 1-3 nieuw.indd 1 15-10-19 16:15 01 hst 1-3 nieuw.indd 2 15-10-19 16:15 Hitlers parachutistengeneraal Kurt Student (1890-1978): een militaire biografie Wouter van den Brandhof Hilversum Verloren 2019 01 hst 1-3 nieuw.indd 3 15-10-19 16:15 De publicatie van dit boek werd mede mogelijk gemaakt door financiële bijdragen van de J.E. Jurriaanse Stichting te Rotterdam, de G.Ph. Verhagen-Stichting te Rot- terdam, de M.A.O.C. Gravin van Bylandt Stichting te ’s-Gravenhage, de gemeente Aalten en AVG Explosieven Opsporing Nederland. Afbeeldingen op het omslag. Voorzijde: de grote foto is een persfoto van het Cle- veland News met daarop afgebeeld Kurt Student, 10 april 1945; kleine foto’s v.l.n.r. Fallschirmjäger te Gennep, 20 september 1944, propagandafoto van het Derde Rijk met daarop afgebeeld een Fallschirmjäger, 11 februari 1939, Student op Kreta tij- dens Unternehmen Merkur, 1941. Achterzijde v.l.n.r. het verwoeste Rotterdam na het bombardement van 14 mei 1940, luchtlandingen van Fallschirmjäger nabij Dordrecht, meidagen 1940, een neergekomen Duits transporttoestel in de regio Delft, meidagen 1940. Bronnen: Beeldbank WO2-niod, Bundesarchiv/Vrijheids- museum Groesbeek en collectie Wouter van den Brandhof Nijmegen. isbn 978 90 8704 817 4 Dit is de handelseditie van een proefschrift verschenen aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen. © 2019 Wouter van den Brandhof Uitgeverij Verloren Torenlaan 25, 1211 ja Hilversum www.verloren.nl Omslagontwerp: Studio Verloren Layout: Rombus, Hilversum Druk: Wilco, Amersfoort No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher. -

Contribution of Greece to the Victory of the Allies During Ww Ii

CONTRIBUTION OF GREECE TO THE VICTORY OF THE ALLIES DURING WW II Lt Colonel of Engineering Panayiotis Spyropoulos Historian of the History Directorate of Hellenic Army General Staff The peninsula of Greece has, since antiquity, been a point of confrontation be- tween East and West, as it constitutes an area of utmost strategic value, situated on the flanks of the main axis of operations in East-West direction and vice-versa. Who- ever occupies Greece can effortlessly with his forces harass the flanks or even the rear of troops operating along the aforementioned axis, control the sea line of com- munication from Gibraltar to Suez, and block from the west the sea route from the Black Sea to Propontis (Marmara) Sea, the Hellespont (Straits), the Aegean Sea and the Mediterranean Sea. The geo-strategic value of Greece has been dramatically enhanced during the XXth century, due to the rapid technological development of war equipment (as per the quote of sir Halford Mackinder on the «Heartland»). During the 2nd World War, Italy launched the attack against Greece, without informing its ally, Germany. Berlin was enraged by the Italian action and considered it «totally incoherent» and mistimed, because it was initiated just before wintertime, a season unsuitable for mountain operations, as well as just before the elections in the (still neutral) USA, providing Roosevelt with even more convincing arguments for go- ing to war. Moreover, it criticised the Italians refraining from any seaborne operation, a fact that facilitated the British in debarking on Crete and other islands, significant for their strategic importance; while they left them the margin to deploy in Thessalo- nica. -

Memorial Services

BATTLE OF CRETE COMMEMORATIONS ATHENS & CRETE, 12-21 MAY 2019 MEMORIAL SERVICES Sunday, 12 May 2019 10.45 – Commemorative service at the Athens Metropolitan Cathedral and wreath-laying at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Syntagma Square Location: Mitropoleos Street - Syntagama Square, Athens Wednesday, 15 May 2019 08.00 – Flag hoisting at the Unknown Soldier Memorial by the 547 AM/TP Regiment Location: Square of the Unknown Soldier (Platia Agnostou Stratioti), Rethymno town Friday, 17 May 2019 11.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Army Cadets Memorial Location: Kolymbari, Region of Chania 11.30 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the 110 Martyrs Memorial Location: Missiria, Region of Rethymno Saturday, 18 May 2019 10.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Memorial to the Fallen Greeks Location: Latzimas, Rethymno Region 11.30 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Australian-Greek Memorial Location: Stavromenos, Region of Rethymno 13.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Greek-Australian Memorial | Presentation of RSL National awards to Cretan students Location: 38, Igoumenou Gavriil Str. (Efedron Axiomatikon Square), Rethymno town 18.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Memorial to the Fallen Inhabitants Location: 1, Kanari Coast, Nea Chora harbour, Chania town 1 18.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Memorial to the Fallen & the Bust of Colonel Stylianos Manioudakis Location: Armeni, Region of Rethymno 19.30 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Peace Memorial for Greeks and Allies Location: Preveli, Region of Rethymno Sunday, 19 May 2019 10.00 – Official doxology Location: Presentation of Mary Metropolitan Church, Rethymno town 11.00 – Memorial service and wreath-laying at the Rethymno Gerndarmerie School Location: 29, N. -

The Newsletter of the Bookham & District University of the Third Age

It’s time again to renew your Please remembermembership to renew your Senior U3A membership before 31 August Moments The Newsletter of the Bookham & District University of the Third Age Issue 51 July 2016 1 From a watercolour painting by Peter Brazier (one time editor of SM) 2 Monday morning Painting Workshop in action! BookhamRegistered Charity Noand 103686 U3A District Membership No 4/239/93 U3A Registered Address: 20 Church Close Fetcham KT22 9BQ www.bookhamu3a.org.uk The Committee he July issue of Senior Moments is always a bit rushed because it is published just two months after the previous issue. The reason for this is because we Tdo not have a monthly meeting in August and the saving in postage costs is considerable. Chairman Vice Chairman There are many interesting articles this time, Neil Carter Lynn Farrell including four by the ‘Farrell’ team and two by Anita 01372 386048 01372 451797 Laycock, another regular contributor, but we also have two members new to contributing to your magazine. I found Cynthia Watson’s piece on architecture particularly pleasing, but it is an interest of mine. I was also very pleased to reproduce a painting by Peter Brazier who apart from being a good watercolour painter is a previous editor Secretary Treasurer Gillian Arnold Chris Pullan of Senior Moments. Lynn and Mike Farrell’s piece on 01372 45204 01372 454582 Crete interested me not just for the content of an island they know well, but it reminded me of the middle book (Officers and Gentlemen) of Evelyn Waugh’s War Trilogy,— Sword of Honour, where he gives a very good insight into the chaos and muddle that must accompany many military operations. -

Bonelli's Eagle and Bull Jumpers: Nature and Culture of Crete

Crete April 2016 Bonelli’s Eagle and Bull Jumpers: Nature and Culture of Crete April 9 - 19, 2016 With Elissa Landre Photo of Chukar by Elissa Landre With a temperate climate, Crete is more pristine than the mainland Greece and has a culture all its own. Crete was once the center of the Minoan civilization (c. 2700–1420 BC), regarded as the earliest recorded civilization in Europe. In addition to birding, we will explore several famous archeological sites, including Knossos and ancient Phaistos, the most important centers of Minoan times. Crete’s landscape is very special: defined by high mountain ranges, deep valleys, fertile plateaus, and caves (including the mythological birthplace of the ancient Greek god, Zeus) Rivers have cut deep, exceptionally beautiful gorges that create a rich presence of geological wealth and have been explored for their aromatic and medicinal plants since Minoan times. Populations of choughs, Griffon Vultures, Lammergeiers, and swifts nest on the steep cliffs. A fantastic variety of birds and plants are found on Crete: not only its resident bird species, which are numerous and include rare and endangered birds, but also the migrants who stop over on Crete during their journeys to and from Africa and Europe. The isolation of Crete from mainland Europe, Asia, and Africa is reflected in the diversity of habitats, flora, and avifauna. The richness of the surroundings results in an impressive bird species list and often unexpected surprises. For example, last year a Blue- cheeked Bee-eater, usually only seen in northern Africa and the Middle East, was spotted. Join us for this unusual and very special trip. -

Greece • Crete • Turkey May 28 - June 22, 2021

GREECE • CRETE • TURKEY MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 Tour Hosts: Dr. Scott Moore Dr. Jason Whitlark organized by GREECE - CRETE - TURKEY / May 28 - June 22, 2021 May 31 Mon ATHENS - CORINTH CANAL - CORINTH – ACROCORINTH - NAFPLION At 8:30a.m. depart from Athens and drive along the coastal highway of Saronic Gulf. Arrive at the Corinth Canal for a brief stop and then continue on to the Acropolis of Corinth. Acro-corinth is the citadel of Corinth. It is situated to the southwest of the ancient city and rises to an elevation of 1883 ft. [574 m.]. Today it is surrounded by walls that are about 1.85 mi. [3 km.] long. The foundations of the fortifications are ancient—going back to the Hellenistic Period. The current walls were built and rebuilt by the Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Ottoman Turks. Climb up and visit the fortress. Then proceed to the Ancient city of Corinth. It was to this megalopolis where the apostle Paul came and worked, established a thriving church, subsequently sending two of his epistles now part of the New Testament. Here, we see all of the sites associated with his ministry: the Agora, the Temple of Apollo, the Roman Odeon, the Bema and Gallio’s Seat. The small local archaeological museum here is an absolute must! In Romans 16:23 Paul mentions his friend Erastus and • • we will see an inscription to him at the site. In the afternoon we will drive to GREECE CRETE TURKEY Nafplion for check-in at hotel followed by dinner and overnight. (B,D) MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 June 1 Tue EPIDAURAUS - MYCENAE - NAFPLION Morning visit to Mycenae where we see the remains of the prehistoric citadel Parthenon, fortified with the Cyclopean Walls, the Lionesses’ Gate, the remains of the Athens Mycenaean Palace and the Tomb of King Agamemnon in which we will actually enter. -

Memorial Services

BATTLE OF CRETE COMMEMORATIONS CRETE, 15-21 MAY 2018 MEMORIAL SERVICES Tuesday, 15 May 2018 11.00 – Commemorative service at the Agia Memorial at the “Brigadier Raptopoulos” military camp Location: Agia, Region of Chania Wednesday, 16 May 2018 08.00 – Flag hoisting at the Unknown Soldier Memorial by the 547 AM/TP Regiment Location: Square of the Unknown Soldier (Platia Agnostou Stratioti), Rethymno town 18.30 – Commemorative service at the Memorial to the Fallen Residents of Nea Chora Location: 1, Kanaris Coast, Nea Chora harbour, Chania town Thursday, 17 May 2018 10.30 – Commemorative service at the Australian-Greek Memorial Location: Stavromenos, Region of Rethymno 11.00 – Commemorative service at the Army Cadets Memorial (followed by speeches at the Orthodox Academy of Crete) Location: Kolymvari, Region of Chania 12.00 – Commemorative service at the Greek-Australian Memorial Location: 38, Igoumenou Gavriil Str., Rethymno town 18.00 – Commemorative service at the Memorial to the Fallen & the Bust of Colonel Stylianos Manioudakis Location: Armeni, Region of Rethymno 19.30 – Commemorative service at the Peace Memorial in Preveli Location: Preveli, Region of Rethymno 1 Friday, 18 May 2018 10.00 – Flag hoisting at Firka Fortress Location: Harbour, Chania town 11.30 – Commemorative service at the 110 Martyrs Memorial Location: Missiria, Region of Rethymno 11.30 – Military marches by the Military Band of the 5th Infantry Brigade Location: Harbour, Chania town 13.00 – Commemorative service at the Battle of 42nd Street Memorial Location: Tsikalaria -

Spatial Distribution and Abundance of the Endangered Fan Mussel Pinna Nobilis Was Investigated in Souda Bay, Crete, Greece

Vol. 8: 45–54, 2009 AQUATIC BIOLOGY Published online December 29 doi: 10.3354/ab00204 Aquat Biol OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Spatial distribution, abundance and habitat use of the protected fan mussel Pinna nobilis in Souda Bay, Crete Stelios Katsanevakis1, 2,*, Maria Thessalou-Legaki2 1Institute of Marine Biological Resources, Hellenic Centre for Marine Research (HCMR), 46.7 km Athens-Sounio, 19013 Anavyssos, Greece 2Department of Zoology–Marine Biology, Faculty of Biology, University of Athens, Panepistimioupolis, 15784 Athens, Greece ABSTRACT: The spatial distribution and abundance of the endangered fan mussel Pinna nobilis was investigated in Souda Bay, Crete, Greece. A density surface modelling approach using survey data from line transects, integrated with a geographic information system, was applied to estimate the population density and abundance of the fan mussel in the study area. Marked zonation of P. nobilis distribution was revealed with a density peak at a depth of ~15 m and practically zero densities in shallow areas (<4 m depth) and at depths >30 m. A hotspot of high density was observed in the south- eastern part of the bay. The highest densities occurred in Caulerpa racemosa and Cymodocea nodosa beds, and the lowest occurred on rocky or unvegetated sandy/muddy bottoms and in Caulerpa pro- lifera beds. The high densities of juvenile fan mussels (almost exclusively of the first age class) observed in dense beds of the invasive alien alga C. racemosa were an indication of either preferen- tial recruitment or reduced juvenile mortality in this habitat type. In C. nodosa beds, mostly large individuals were observed. The total abundance of the species was estimated as 130 900 individuals with a 95% confidence interval of 100 600 to 170 400 individuals. -

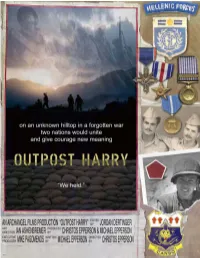

Outpost Harry

OUTPOST HARRY U.S. Veteran Interviews The Outpost Harry film crew attended the 15th annual reunion of the Outpost Harry Survivors Association held from June 15th through June 18th at the Marriott Hotel in downtown Des Moines Iowa. This reunion commemorated the 53rd year anniversary of the battle for Outpost Harry. 32 veterans were interviewed for the film. Donors continued from Page 6 Robert H (Bob) Baker, Sam Buck, Lupe P Carrasco, Dan Carson, Peter Chacho, Jack Coffey, Jerry Cunningham, James H Davis, James E Day, Robert Dornfried, James W. Evans, Henry W. Flaack, John Gallaspy, Leonard E Godmaire, Edward J Hanrahan Jr., James Jarboe, Richard R. Kilgen, Gerrard F Lang, Gordon B Lowery, Joseph E. Manley, Martin Markley, Richard L Martinet, James K. McQueen, Robert H Orheim, Don R Patton, Francis X Riley, Raymond J Scherrman, Charles Scott, Charles Seeman, Philip C. Smith, Claude L Williams, Mark H Woods and Stanley Zatorski. Thank you all for your generous support! Fueled with an ample supply of coffee Editor, Jordan Dertinger, goes through the photographs from one of our ARCHANGEL FILMS CREW OP Harry veterans photo albums. He is organizing a large reference library and scanning those that might be used in JOINS US AT THE REUNION the OP Harry Documentary. (Jarboe) During the reunion 28 interviews were conducted A group of enthusiastic young independent and much research information was collected. At the documentary filmmakers from Archangel Films attended end of the reunion the film crew moved on to the the reunion in Des Moines this year. They set up a suite Washington DC area from Des Moines to interview near our meeting rooms to film and record interviews retired MG Jack Singlaub who commanded a Bn. -

Churchill, Wavell and Greece, 1941*

Robin Higham Duty, Honor and Grand Strategy: Churchill, Wavell and Greece, 1941* In our previous works, then Capt. Harold E. Raugh and I took too limited a Mediterranean view of the background of the Greek campaign of 6-26 April 19411. Far from its being Raugh’s “disastrous mistake,” I argue that General Sir Archibald Wavell’s actions fitted both traditional British practice and the general policy worked out in London. In 1986 and 1987 I argued after long and careful thought since 1967 that Wavell went to Greece as part of a loyal deception of Prime Minister Winston Churchill, whose bellicose way at war was the antithesis of Wavell’s own professionalism. Further, whereas Raugh took the narrow military view, mine was a grand-strategic approach relating ends to means. My argument here is that a restudy of the campaign in Greece of 6-27 April 1941 utilizing the Orange Leonard ULTRA messages reconfirms my thesis that going to Greece was a deception and that far from being the miserable defeat which Raugh imagined, the withdrawal was a strategic triumph in the manner of a Wellington in Spain and Portugal or of the BEF’s in France in 1940. For this Wavell deserves full credit. In this respect, then, the so-called campaign in Greece must be seen not as an ignominious retreat in the face of superior forces, but rather as a skilful, carefully planned withdrawal and ultimate evacuation. It was a successful, though materially costly, gamble. * This paper was accepted for publication in late 2005 but delayed by the Balkan Studies financial crisis.