A Theological Review of Approaching Models in the Dialog of Faith and Science

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revelation and Inspiration and the Bible

Revelation and Inspiration and the Bible REVELATION is that act by which God discloses Himself or communicates truth to the mind. We can talk about two kinds of revelation. First there is general revelation - the revelation of God in creation. Psalm 19:1-6 reflects this. Romans 1:19- 20 teaches us that God's attributes, power and divine nature are clearly seen, being understood from what is made. Creation will always wear the "fingerprints" of the Creator. However, Psalm 19:7-14 refers to the the form of revelation, whereby God reveals his will - which we call special revelation - nature cannot reveal moral and spiritual responsibilities - these are communicated verbally. Adam and Eve in the garden had both. Before the fall, they could see clearly God revealed in creation and had his spoken commandments (Gen. 1:28,2:16,17) . They were in personal communication with God. Romans 1:18-25 teaches us that general revelation is sufficient to leave man inexcusable for disbelief, but insufficient for salvation. This is due in part to the fallenness of man, his heart and reason darkened so he cannot understand and he has "suppressed the truth in unrighteousness." Professing wisdom, they became fools, exchanging God for created things- worshipping creation rather than the Creator. (Rom 1:25) As a result they live lives controlled by lusts and passions and darkened minds. (vs. 38) Further there was no need to "build" revelation concerning God's redemption into the creation of a perfect unfallen world. Now that man is fallen, and needs redemption- he needs that special revelation that reveals God's redemptive activity (Rom 10:8-17.) We need special revelation (God's spoken self-disclosure) to correctly perceive Him in the creation and as redeemer and Lord. -

Revelation & Social Reality

Revelation & Social Reality Learning to Translate What Is Written into Reality Paul Lample Palabra Publications Copyright © 2009 by Palabra Publications All rights reserved. Published March 2009. ISBN 978-1-890101-70-1 Palabra Publications 7369 Westport Place West Palm Beach, Florida 33413 U.S.A. 1-561-697-9823 1-561-697-9815 (fax) [email protected] www.palabrapublications.com Cover photograph: Ryan Lash O thou who longest for spiritual attributes, goodly deeds, and truthful and beneficial words! The outcome of these things is an upraised heaven, an outspread earth, rising suns, gleaming moons, scintillating stars, crystal fountains, flowing rivers, subtle atmospheres, sublime palaces, lofty trees, heavenly fruits, rich harvests, warbling birds, crimson leaves, and perfumed blossoms. Thus I say: “Have mercy, have mercy O my Lord, the All-Merciful, upon my blameworthy attributes, my wicked deeds, my unseemly acts, and my deceitful and injurious words!” For the outcome of these is realized in the contingent realm as hell and hellfire, and the infernal and fetid trees, as utter malevolence, loathsome things, sicknesses, misery, pollution, and war and destruction.1 —BAHÁ’U’LLÁH It is clear and evident, therefore, that the first bestowal of God is the Word, and its discoverer and recipient is the power of understanding. This Word is the foremost instructor in the school of existence and the revealer of Him Who is the Almighty. All that is seen is visible only through the light of its wisdom. All that is manifest is but a token -

Bibliology the Study of the Bible

Bibliology The Study of the Bible Copyright First AG Leadership College 2008 17 Jalan Sayor, off Jalan Pudu Kuala Lumpur, 55100 Malaysia Phone: 03 21446773 Fax: 03 21424895 E-Mail [email protected] Bibliology Bibliology Chapter One: REVELATION OF CHRIST REVELATION 1. Audrey Millard J. Erickson writes: “Because man is finite and God is infinite, if man is to know God it must come about by God’s revelation of Himself to man. By this we mean God’s manifestation of Himself to man in such a way that man can know and fellowship with Him.” (Erickson 1983:153). 2. There are two reasons why revelation is necessary for us to know God: (a) We are creatures. Bruce Milne writes: “In the beginning God created … man”. (Gen 1:1,27). These first words of the Bible express the distinction between God and mankind. God as the Creator exists freely apart from ourselves; the creature depends utterly on God for existence (cf man and woman as “dust” in Gen 2:7; 3:19; Ps 103:14). God and mankind therefore belong to different orders of being. This distinction is not absolute. We are made “in the image of God”; God communicates with us (Gen 1:28 etc.); God became man in the Lord Jesus Christ (Jn 1:1,14); God the Spirit indwells Christians and brings them into a personal relationship to God (Rom 8:9-17). All these factors confirm a degree of correspondence between God and humanity. Yet a profound, irreducible distinction remains. This distinction in being involves a distinction in knowing; “who among men knows the thought of a man except the man’s spirit within him? In the same way no-one knows the thoughts of God except the Spirit of God”. -

'Solved by Sacrifice' : Austin Farrer, Fideism, and The

‘SOLVED BY SACRIFICE’ : AUSTIN FARRER, FIDEISM, AND THE EVIDENCE OF FAITH Robert Carroll MacSwain A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St. Andrews 2010 Full metadata for this item is available in the St Andrews Digital Research Repository at: https://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/920 This item is protected by original copyright ‘SOLVED BY SACRIFICE’: Austin Farrer, Fideism, and the Evidence of Faith Robert Carroll MacSwain A thesis submitted to the School of Divinity of the University of St Andrews in candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The saints confute the logicians, but they do not confute them by logic but by sanctity. They do not prove the real connection between the religious symbols and the everyday realities by logical demonstration, but by life. Solvitur ambulando, said someone about Zeno’s paradox, which proves the impossibility of physical motion. It is solved by walking. Solvitur immolando, says the saint, about the paradox of the logicians. It is solved by sacrifice. —Austin Farrer v ABSTRACT 1. A perennial (if controversial) concern in both theology and philosophy of religion is whether religious belief is ‘reasonable’. Austin Farrer (1904-1968) is widely thought to affirm a positive answer to this concern. Chapter One surveys three interpretations of Farrer on ‘the believer’s reasons’ and thus sets the stage for our investigation into the development of his religious epistemology. 2. The disputed question of whether Farrer became ‘a sort of fideist’ is complicated by the many definitions of fideism. -

Progressive Revelation

PROGRESSIVE REVELATION THE Protevangelium, God's word of salvation to fallen man in Paradise, is the beginning of the special revelation contained in the Bible. Only in Eden has general revelation been adequate to the needs of man. Man having fallen, " God breaks His way in a round-about fashion into man's darkened heart to reveal there His redemptive love. By slow steps and gradual stages He at once works out His saving purpose and moulds the world for its reception, choosing a people for Himself and training it through long and weary ages, until at last when the fulness of time has come, He bares His arm and sends out the proclamation of His great salvation to all the earth " (Warfield). The whole history of salvation is one coming of God to His people, one speech of grace to man. It is an historical revelation given first through patriarchs and prophets and ultimately in the Son-a revelation essentially different from the general manifestation of God, e.g. in the works of His hands or in the rational nature of man, because it is redemptive in purpose and soteriological in character. This "word" of God is a revelation of grace and salvation. Under the old covenant men served as the medium through which this word was sounded, until finally the whole revelation is summed up in the one moment of incarnation, when the Word Himself became flesh. It seems quite evident, therefore, that God chose to give the revelation of His grace only progressively, or in other words through the process of an historical development. -

General Revelation

Scholars Crossing SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations 12-1983 Review: General Revelation W. David Beck Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs Recommended Citation Beck, W. David, "Review: General Revelation" (1983). SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations. 82. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/sor_fac_pubs/82 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in SOR Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 462 JOURNAL OF THE EVANGELICAL THEOLOGICAL SOCIETY and more Biblical designation of God's creative act than creatio ex nihilo (p. 51, Appendix D). He does not attempt to relate the details of Genesis 1 to scientific data, believing that whereas scientific explanations deal with secondary causation the ' 'language of creation," theological language, is that of divine, fiat causation (pp. 62, 246). Appealing to the ' 'literary framework" understanding of Genesis 1, he suggests that the six days are days of revelation about creation, not days or periods of creation itself (pp. 58-59). On the question of the literary genre of Genesis 1 he suggests that the text is best understood by viewing its ''polemical intent" to counter the magic and idolatry of ancient Near Eastern polytheism and to lead man to live a godly life before the one true Creator (pp. 62-66). Houston deals with the nature of man, as God's image-bearer, in terms of man's stew ardship or "sovereignty" over other creatures, his responsibility to God, and his "rela tional" nature with respect to God and mankind (pp. -

Question 38 - Can General Revelation in and by Itself Bring Someone to a Saving Knowledge of Jesus Christ?

Liberty University Scholars Crossing 101 Most Asked Questions 101 Most Asked Questions About the Bible 1-2019 Question 38 - Can General Revelation in and by itself bring someone to a saving knowledge of Jesus Christ? Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/questions_101 Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "Question 38 - Can General Revelation in and by itself bring someone to a saving knowledge of Jesus Christ?" (2019). 101 Most Asked Questions. 12. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/questions_101/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the 101 Most Asked Questions About the Bible at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in 101 Most Asked Questions by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 101 MOST ASKED QUESTIONS ABOUT THE BIBLE 38. Can General Revelation in and by itself bring someone to a saving knowledge of Jesus Christ? Theologian Millard Erickson responds as follows: “But what of the judgment of man, spoken of by Paul in Romans 1 and 2? If it is just for God to condemn man, and if man can become guilty without having known God’s special revelation, does that mean that man without special revelation can do what will enable him to avoid the condemnation of God? In Rom. 2:14 Paul says: ‘When Gentiles who have not the law, do by nature what the law requires, they are a law to themselves, even though they do not have the law.’ Is Paul suggesting that they could have fulfilled the requirements of the law? “What if someone then were to throw himself upon the mercy of God, not knowing upon what basis that mercy was provided? Would he not in a sense be in the same situation as the Old Testament believers? The doctrine of Christ and his atoning work had not been fully revealed to these people. -

GCSE Revision the Existence of God and Revelation Revision Guide

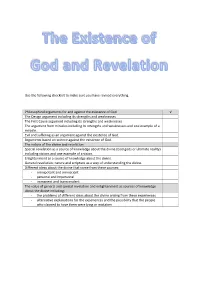

Use the following checklist to make sure you have revised everything. Philosophical arguments for and against the existence of God √ The Design argument including its strengths and weaknesses. The First Cause argument including its strengths and weaknesses The argument from miracles including its strengths and weaknesses and one example of a miracle. Evil and suffering as an argument against the existence of God. Arguments based on science against the existence of God. The nature of the divine and revelation Special revelation as a source of knowledge about the divine (God gods or ultimate reality) including visions and one example of a vision. Enlightenment as a source of knowledge about the divine. General revelation: nature and scripture as a way of understanding the divine. Different ideas about the divine that come from these sources: - omnipotent and omniscient - personal and impersonal - immanent and transcendent. The value of general and special revelation and enlightenment as sources of knowledge about the divine including: - the problems of different ideas about the divine arising from these experiences - alternative explanations for the experiences and the possibility that the people who claimed to have them were lying or mistaken Agnostic: Belief that there is insufficient evidence to say whether God exists or not. All-compassionate: Characteristic of God; all-loving, omnibenevolent. All-merciful: Characteristic of God; always forgiving and never vindictive. Atheism: Belief that there is no God. Benevolent: Characteristic of God; all-loving. Conscience: Sense of right and wrong; seen as the voice of God within our mind by many religious believers. Design argument: Also known as teleological argument. -

AQA Religious Studies C – Existence of God and Revelation

AQA Religious Studies C – Existence of God and Revelation Design argument Key terms The Design Argument argues that God must exist because the world around us is so intricate and well-designed that there must be an intelligent creator behind it. Atheist Someone who does not William Paley puts this forward in his Watchmaker’s Argument that says if you found a watch in the grass you would not assume its intricate believe a God exists Theist Someone who believes mechanism had come about by accident, you would assume someone had created it. The same applies for the world around us. in a God or Gods Atheists argue that nature and science are responsible for the world around us and that much of the so-called design is the result of chance Benevolent God’s nature as all- and natural selection. loving and all-good First Cause The First Cause Argument was put forward by Thomas Aquinas and it argues that there has to be an uncaused cause that made everything Omnipotent God’s nature as argument else happen and that must be God. It argues that nothing moves without first being pushed and that God is the only possible being that can all-powerful exist with no cause as God is eternal (never beginning, never ending) Omniscient God’s nature as all- knowing and aware of all that Atheists argue that by this logic God must have a cause or that if God is eternal then the universe itself could be eternal as well. has happened past, present, Argument from The Argument from Miracles argues that miracles (a remarkable event seemingly only explained by God’s actions) prove that God exists. -

General Revelation Approach to Salvific Hypostasis and Its Reinterpretation of Biblical Christology

Journal of Religion and Theology Volume 3, Issue 1, 2019, PP 29-38 ISSN 2637-5907 General Revelation Approach to Salvific Hypostasis and its Reinterpretation of Biblical Christology Kiatezua Lubanzadio Luyaluka, Ph. D. (Hon.) Kiatezua Lubanzadio Luyaluka, Ph. D. (hon.) Institut des Sciences Animiques Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo *Corresponding Author: Kiatezua Lubanzadio Luyaluka has a PhD (honors) degree from Trinity Graduate School of Apologetics and Theology, Kerala, India. Email : [email protected] ABSTRACT This paper capitalizes on a cosmological argument to demonstrate that the hypostatic nature of man is the result of a double relationship in which the Children of God in heaven abide: a unity with the Most-high manifested in the presence of the Word, the fullness of divinity in and around them, and the existence of a tempting potential evil which any bad exercice of free will might actualize. The first relationship, coupled with the absolute non-contingency of the Most-high, translates in the presence of the divne nature in man and the second relationship actualized acounts for the limitations of man. Substantianting the explicit salvific import of this paradigm and its anthropology as the brand of African tradtional religion, the paper uses it to reinterpret the hypostasis of Jesus in light of the KCA. Keywords: Christology; hypostasis; cosmological argument; Bukôngo; Jesus; salvation INTRODUCTION explain how divinity and humanity are related one to another in 1Jesus. This issue was addressed by The word hypostasis is from the Greek u`po, stasij - hupostasis - which alludes to an entity’s the Fifth Council of Constantinople (AD 553) basic or essential nature. -

The Problem of Revelation

THE PROBLEM OF REVELATION Regarding the basic meaning of the term "revelation" there is a fair degree of consensus in our time. The term may be defined either phe- nomenologically or theologically. Phenomenologically, it signifies a sud- den or unexpected disclosure of a deeply meaningful truth or reality. Revelation usually connotes that the new awareness or knowledge comes upon one as a gift, that it answers a real need, and that it effects a wonderful transformation in the recipient. Theologically, revelation signifies an action of God by which he makes known himself or something he intends to manifest. The theo- logical notion of revelation presupposes, or at least implies, that God exists and has dealings with the world. Divine revelation, according to Christian theologians, is a gift; it answers a real need—delivery from darkness and death—and makes a profound difference, inasmuch as it "justifies" or "saves" those who would otherwise perish. Christians believe that God's revealing action undergirds the faith of ancient Israel and that of the Christian Church. The Bible, which expresses this histor- ical faith, is accordingly viewed as a primary document of revelation. Notwithstanding these basic agreements there is no consensus among Christian or Catholic theologians as to the forms in which revela- tion comes, where it is principally found, or how it is related to faith. In the present paper I shall seek to classify and evaluate some of the most prominent modern theories.1 My own concern is with the logical schematization of positions, but in order to give concreteness and actuality to the analysis I shall take the risk of naming some authors as representatives of the various points of view. -

Revelation in Christian Theology

11 Revelation in Christian Theology Glen E. Harris Jr. Christianity is a revealed religion. We do not embark on the theological task desiring to study God in himself (archetypal knowledge), but as he has revealed himself (ectypal knowledge). Most people who make concessions for the concept of divine revelation agree upon this assertion, but deduce very different conclusions from it. In the Bible, the idea of revelation generally means ‘unmasking’ or ‘unveiling’ of that which was previously unknown. The Hebrew and Greek terms which lie behind these words refer to a host of divine activities from theophanies to apocalyptic manifestations, from God’s handiwork in the cosmos to the work of grace in the human heart.1 Because of the naturalism that is so pervasive in modern theology, some have argued that the biblical idea of revelation (theophanies, apocalyptics, etc.) is inconsistent with modern dogmatics, not to mention phenomenologically untenable. Gerald F. Downing is one such theologian. Downing has argued that these biblical ideas are wholly inconsistent with the contemporary doctrines of revelation in the form of theological propositions or existential experience, which, he notes, can only be traced back to the era after the Enlightenment. In his opinion, because the modern idea of revelation is inconsistent with both the biblical usage and the pre-Enlightenment Christian tradition, it should be abandoned. Revelation is not central to the theological task because of its ethereal nature. He goes so far as to deny the possibility of a present form of divine revelation (adhering to the biblical usage) and relegates it to the eschaton.2 Knowledge of God will come only when he shows himself finally and ultimately in the Parousia, he argues.