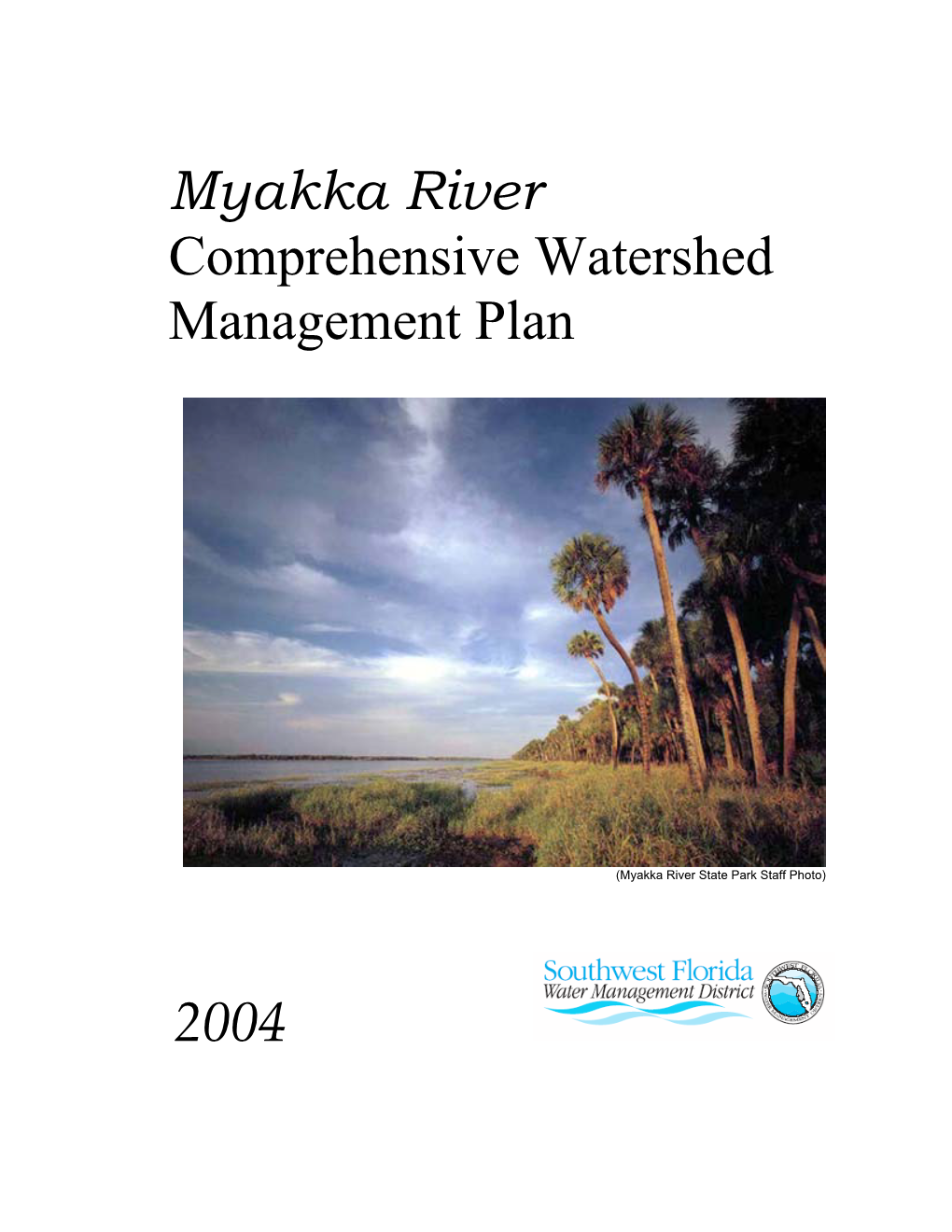

Myakka River Comprehensive Watershed Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2001 SWFWMD Land Acquisition Plan

Five-Year Land Acquisition Plan 2001 SWFWMD i Land Acquisition Five-Year Plan 2001 Southwest Florida Water Management District Five-Year Land Acquisition Plan 2001 If a disabled individual wishes to obtain the information contained in this document in another form, please contact Cheryl Hill at 1-800-423-1476, extension 4452; TDD ONLY 1-800-231-6103; FAX (352)754-68771 ii Table of Contents Table of Contents Introduction and History 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 1 Save Our Rivers 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 1 Preservation 2000 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 1 Florida Forever 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 3 Selection and Evaluation Process 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 5 Less-Than-Fee Acquisitions 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 10 Partnerships 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 13 Surplus Lands111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 16 Land Use/Management Activities111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 17 Management Planning 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 17 Land Use Implementation 111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 -

Florida Communities Trust Annual Report 2016-2017

Florida Communities Trust Annual Report Fiscal Year 2016-2017 Office of Operations Land and Recreation Grants Section Florida Department of Environmental Protection September 30, 2017 3900 Commonwealth Boulevard, MS 103 Tallahassee, Florida 32399-3000 www.dep.state.fl.us Florida Communities Trust Annual Report Fiscal Year 2016-2017 1 Table of Contents LETTER FROM THE CHAIR ....................................................................................................... 1 PROJECT LOCATION MAP ........................................................................................................ 2 FLORIDA COMMUNITIES TRUST .............................................................................................. 3 MISSION AND ACCOMPLISHMENTS ......................................................................................... 4 PARK HAPPENINGS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2016-2017 ................................................................ 8 ACQUIRED PROJECTS BY COUNTY 1991-2017 .................................................................... 12 SUMMARY OF FINANCIAL ACTIVITIES ................................................................................... 29 FLORIDA COMMUNITIES TRUST BOARD MEMBERS ............................................................ 31 Front Cover Photo: Victory Pointe Park (f.k.a. West Lake Park) Unique Abilities 2017 Cycle FCT # 16-005-UA17, City of Clermont, FL Back Cover Photo: Myers-Stickel Property Unique Abilities 2017 Cycle FCT # 16-012-UA17, St. Lucie County, FL Florida Communities Trust -

Natural Systems

Natural Systems NATURAL SYSTEMS INTRODUCTION Natural resources in Southwest Florida have had a major influence on the area’s economic development and growth. The most important of these resources are the Region’s location and climate, land and water resources, vegetation and wildlife, and inland and tidal wetlands. These resources have attracted the large number of retirees and tourists to the region, thereby fueling the area’s service, trade, and construction industries. THE CLIMATE Temperature Due to the Region's southerly location, a near-subtropical climate with an associated high annual rainfall is typical. Average monthly temperatures range from 64.3 degrees Fahrenheit in January to 82.6 degrees Fahrenheit in August. Freezes are not common in the Region, but may occur once or twice a year. "Jacket weather" occurs periodically during the fall and winter months. Weather and climate are very important factors in the economy of Southwest Florida. The combination of warm weather, decreased humidity, and low rainfall during the winter months encourages tourism and an influx of seasonal residents. A high yearly rainfall and moderate winter temperatures enable agriculture to thrive year-round. Periods of freezing weather, when they occur, have adverse effects upon the local economy. Unusually severe winter freezes and resulting agricultural losses in other parts of the state have caused a migration of agricultural interests into the Region from counties to the north. Precipitation Patterns Patterns of precipitation in Southwest Florida exhibit strong seasonal variations. The Region enjoys a rainy season from May through October and a dry season from November through April. Increased atmospheric moisture and incoming solar radiation levels in May generally trigger the rainy season, while a reversal of these conditions occurs in September to signal the start of the dry season. -

Section I Notices of Development of Proposed Rules and Negotiated Rulemaking

Florida Administrative Weekly Volume 34, Number 32, August 8, 2008 Section I PURPOSE AND EFFECT: The purpose of the rule Notices of Development of Proposed Rules development is to address the newly required designations for Major Areas of Interest, accelerated coursework, career and Negotiated Rulemaking education certification, and Ready to Work credential, on the standard high school diploma. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION SUBJECT AREA TO BE ADDRESSED: Diploma State Board of Education Designations. RULE NO.: RULE TITLE: SPECIFIC AUTHORITY: 1001.02, 1003.428, 1003.429, 6A-1.09422 Florida Comprehensive Assessment 1003.438 FS. Test Requirements LAW IMPLEMENTED: 15.03(3), 1001.02, 1003.428, PURPOSE AND EFFECT: The purpose of the rule 1003.4285, 1003.429, 1003.43, 1003.438 FS. development is to amend the rule to remove the passing score IF REQUESTED IN WRITING AND NOT DEEMED on the grade 10 FCAT Writing+ to qualify for a standard high UNNECESSARY BY THE AGENCY HEAD, A RULE school diploma and to remove the current grade-level scale DEVELOPMENT WORKSHOP WILL BE HELD AT THE scores in order to comply with Senate Bill (SB) 1908. SB 1908 DATE, TIME AND PLACE SHOWN BELOW: requires that the Commissioner discontinue administration of DATE AND TIME: August 28, 2008, 9:00 a.m. the multiple-choice test items on the comprehensive PLACE: Call 1(888)808-6959, code: 4137943 assessment of writing until a new comprehensive test of THE PERSON TO BE CONTACTED REGARDING THE writing is administered in 2012-2013. Until 2012-2013, the PROPOSED RULE DEVELOPMENT AND A COPY OF comprehensive assessment of writing will consist of an essay THE PRELIMINARY DRAFT IS: Holly Edenfield, Executive to be scored on a scale of 1 to 6. -

Recommended Minimum Flows for the Chassahowitzka River System

Recommended Minimum Flows For the Chassahowitzka River System Photo: W. Sotera October 30, 2012 Michael G. Heyl, Doug Leeper, Ron Basso Southwest Florida Water Management District Brooksville, Florida 34604-6899 and Marty Kelly (Formerly with Southwest Florida Water Management District) With contributions by Balanced Environmental Management Systems, Inc. ChassMFL_Final.docx Last Save: 12/11/2012 9:18 AM ii ChassMFL_Final.docx Last Save: 12/11/2012 9:18 AM Recommended Minimum Flows for the Chassahowitzka River System October 30, 2012 Michael G. Heyl, Doug Leeper, Ron Basso Southwest Florida Water Management District Brooksville, Florida 34604-6899 and Marty Kelly (Formerly with Southwest Florida Water Management District) With contributions by Balanced Environmental Management Systems, Inc. Prime Contractor The Southwest Florida Water Management District (District) does not discriminate on the basis of disability. This nondiscrimination policy involves every aspect of the District's functions, including access to and participation in the District's programs and activities. Anyone requiring reasonable accommodation as provided for in the Americans with Disabilities Act should contact the District's Human Resources Bureau Chief, 2379 Broad Street, Brooksville, Florida 34604-6899; telephone (352) 796-7211, ext. 4702 or 1-800-423-1476 (FL only), ext. 4702; TDD (FL only) 1-800-231-6103; or email to [email protected]. iii ChassMFL_Final.docx Last Save: 12/11/2012 9:18 AM Acknowledgements We would like to thank several of our colleagues at the Southwest Florida Water Management District for their contributions and useful suggestions concerning the work summarized in this report We are also indebted to District staff who conducted field sampling for the project (Don Hampton, Courtney James, Tammy Hinkle, Jason Hood and Richard Gant) and to Barbara Matrone for her assistance in document production. -

Myakka River State Park Unit Management Plan Approved

MYAKKA RIVER STATE PARK UNIT MANAGEMENT PLAN APPROVED STATE OF FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Division of Recreation and Parks December 7, 2004 Department of Environmental Protection Marjory Stoneman Douglas Building Jeb Bush 3900 Commonwealth Boulevard, MS 140 Colleen Castille Governor Tallahassee, Florida 32399-3000 Secretary Phone: (850) 245-2784 Fax: (850) 245-2786 December 7, 2004 Ms. BryAnne White Office of Park Planning Division of Recreation and Parks 3900 Commonwealth Blvd.; M.S. 525 Tallahassee, Florida 32399 Re: Myakka River State Park Lease # 3636 Ms. White: On October 15, 2004, the Acquisition and Restoration Council recommended approval of theMyakka River State Park management plan. On December 7, 2004, the Office of Environmental Services, acting as agent for the Board of Trustees of the Internal Improvement Trust Fund, approved the management plan for the Myakka River State Park. Pursuant to Section 253.034, Florida Statutes, and Chapter 18-2, Florida Administrative Code this plan’s ten-year update will be due on December 7, 2014. Approval of this land management plan does not waive the authority or jurisdiction of any governmental entity that may have an interest in this project. Implementation of any upland activities proposed by this management plan may require a permit or other authorization from federal and state agencies having regulatory jurisdiction over those particular activities. Pursuant to the conditions of your lease, please forward copies of all permits to this office upon issuance. Sincerely, Paula L. Allen Office of Environmental Services Division of State Lands Department of Environmental Protection "More Protection, Less Process” Printed on recycled paper. -

Myakka River State Park

Myakka River State Park Acquisition and Restoration Council Draft Unit Management Plan STATE OF FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Division of Recreation and Parks June 2018 Executive Summary Lead Agency: Department of Environmental Protection Division of Recreation and Parks Common Name of Property: Myakka River State Park Location: Sarasota and Manatee counties Acreage: 37,198.91 Acres Acreage Breakdown Natural Communities Acres Mesic Flatwoods 3766.16 Dry Prairie 14771.03 Mesic Hammock 673.43 Scrubby Flatwoods 182.44 Sinkhole 1.98 Basin Swamp 994.75 Baygall 293.40 Depression Marsh 6788.86 Dome Swamp 8.91 Floodplain Marsh 1181.81 River Floodplain Lake 1218.09 Blackwater Stream 142.57 Developed 75.03 Canal/Ditch 7.70 Artificial Pond 27.00 Abandoned Field 48.96 Abandoned Pasture 565.73 Spoil Area 3.14 Utility Corridor 96.57 Lease/Management Agreement Number: 2324 Use: Single Use Management Responsibilities Agency: Dept. of Environmental Protection, Division of Recreation and Parks Responsibility: Public Outdoor Recreation and Conservation Designated Land Use: Public outdoor recreation and conservation is the designated single use of the property. Sublease: None Encumbrances: None 1 Executive Summary Unique Features Overview: Myakka River State Park is located east of Sarasota in Sarasota and Manatee Counties Access to the park is from Interstate 75, exit 205 (State Road 72); the entrance is 9 miles east on State Road 72/Clark Rd. The park centers around Myakka River. The park was initially acquired in 1934. Currently, the park comprises 37,198.91 acres. The purpose of Myakka River State Park is to preserve the natural beauty, wildlife, and historical features of the property, to serve as an important link in the chain of protected lands in the southern portion of the state, and to provide outstanding outdoor recreation and natural resource interpretation for the benefit of the people of Florida. -

State of Florida Deepwater Horizon Project Proposals Updated 9/5/2014

State of Florida Deepwater Horizon Project Proposals Updated 9/5/2014 Project Geographic Confirmation Florida FTP Hyperlink to Project Title Abbreviated Project Description Watershed Estimated Cost Submitted By Latitude Longitude Number Region Number Counties Proposals 1 Southwest 1-020213 Fruit Farm Creek Mangrove Total project size is 1,025 acres. The project would restore historical hydrologic Everglades West Collier $1,940,000 Coastal Resources 25.923228 -81.660206 1-020213 Collier_Fruit Restoration Project connections across CR 92 in Collier County to restore 64 acres of dead mangroves, Coast; Everglades Group, Inc. Farm Creek permanently prevent future immediate death of 161 acres of severely stressed mangroves, and conserve and forestall death of an additional 800 acres of mangroves until further work could be undertaken (During Phase 3 not described here). Total restored or conserved: 1,025 acres. 2 Statewide 2-021313 Enhancing Community The Florida Emergency Preparedness Association (FEPA) is a statewide association of All FL Watersheds Statewide $100,000 Florida Emergency 0.000000 0.000000 2-021313 Resiliency through Florida emergency management professionals. Under this project, FEPA proposes to Preparedness Statewide_Communit Coordination and Cooperation sponsor a multi-day interactive forum to discuss emergency planning and mitigation Association y Resiliency measures to improve coordination at all levels of government and the private sector to address a broad range of hazards. FEPA is unique in that it includes representatives from all response disciplines as well as key private sector partners. 3 Atlantic 3-021313 Torry Island Pond Apple Forest This is an ongoing project (which has been on hold due to lack of funding) to restore Lake Okeechobee; Palm Beach $250,000 Arthur R. -

State 404 Program Applicant's Handbook

STATE 404 PROGRAM APPLICANT’S HANDBOOK This Handbook, including Appendices A and B only is incorporated by reference in subsection 62-331.010(5), F.A.C. Effective [date] FOR: FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Introduction The Florida Department of Environmental Protection (“Department” or “DEP”) developed this Applicant’s Handbook to help persons understand the rules, procedures, standards, and criteria that apply to the State 404 Program under Part IV of Chapter 373 of the Florida Statutes (F.S.). The Department administers and implements the State 404 Program. In the event the Department seeks and receives approval from EPA pursuant to 40 CFR 233.16 to modify the program to delegate implementation of the State 404 Program to Florida’s five Water Management Districts (“Districts”), the Districts may then implement the program with Department oversight. The State 404 Program Applicant’s Handbook refers to these entities collectively as “Agencies” and also refers to one or more water management districts as “District” or “Districts” (capitalized), respectively. The term “district” (lower case) generally refers to the main or field offices of either the Department or District. The Districts are: Northwest Florida Water Management District (NWFWMD) Suwannee River Water Management District (SRWMD) St. Johns River Water Management District (SJRWMD) Southwest Florida Water Management District (SWFWMD) South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD) The primary State 404 Program rules are adopted by DEP as Chapter 62-331 of the Florida Administrative Code (F.A.C.). This Applicant’s Handbook is incorporated by reference in subsection 62-331.010(5), F.A.C., and therefore operates as a rule of the Agencies. -

Bryan T. Veith, P.E., F.ASCE

President / Engineer & Business Consultant Bryan T. Veith, P.E., F.ASCE Experience Highlights Bryan Veith has over 26 years of “One Water” and public/private civil engineering experience including advanced water and wastewater treatment plants, integrated water resources, pumping stations, pipelines and trenchless technologies, reclaimed water systems, water supply and deep injection wells, stormwater management systems, site-civil, site planning, and biosolids to energy. Professional services have included business consulting, master planning/studies, piloting, modeling, engineering and design, construction management/CEI, permitting/regulatory assistance, asset management, funding assistance, public/stakeholder involvement, and alternative project delivery (i.e. Design Build, CMAR). He has served in various roles for projects throughout Florida and the US such as: Multi-office (region) area leader Business service line leader Project director Client services manager Business Consultant Senior project manager Quality Control New Initiative Leader Technical Leader Business Consulting / Asset Management Education Business Plan Development Assistance, SWFWMD, Brooksville, FL M.S., Environmental Engineering, University of South Florida, 1999 CSM/Project Manager. Provided business consulting to assist the District with development of their first Business Plan to clarify and to document the staff B.S., Civil Engineering, University of Florida, 1993 and financial resources needed to meet the District’s initiatives and goals -- some -

Assessment of Cyanotoxins in Florida's Surface Waters and Associated Drinking Water Resources

Assessment of Cyanotoxins in Florida’s Surface Waters and Associated Drinking Water Resources FINAL REPORT April 11, 2006 Christopher D. Williams Cyanobacteria Survey Project Coordinator St. Johns River Water Management District Palatka, FL 32178 BCI Engineers and Scientists Lakeland, Fl. 33803 John Burns Cyanobacteria Survey Project Manager St. Johns River Water Management District Palatka, FL. 32178 Andrew Chapman Environmental Scientist Cyanobacteria Survey Project Taxonomist St. Johns River Water Management District Palatka, FL. 32178 Marek Pawlowicz Biological Scientist III Bureau of Laboratories Florida Department of Health Jacksonville, FL. 32202 Wayne Carmichael Professor of Aquatic Biology/Toxicology Department of Biological Sciences Wright State University Dayton, OH. 45435 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Cyanobacteria are prevalent components of Florida’s surface fresh and estuarine waters and are known to produce toxins that have been linked to liver disease, kidney damage, genotoxicity, human cancer, and death. Upon “bloom” formation these events may pose a threat to public health when observed in recreational and/or drinking water supplies. Since 1999, the Florida Harmful Algal Bloom Task Force has supported statewide surveillance of cyanobacteria in surface waters and drinking water supplies. Dominant algal taxa that formed toxigenic blooms included Microcystis, Anabaena, Cylindrospermopsis, Aphanizomenon, Planktothrix, and Lyngbya. Toxins characterized by this monitoring project, via analyses performed by Wright State University and the Bureau of Laboratories at the Florida Department of Health, included microcystins, anatoxin-a, cylindrospermopsin, and debromoaplysiatoxin. The identification of cylindrospermopsin and debromoaplysiatoxin represent new records for such toxins in North America. In 1999, eighty percent of the blooms sampled and analyzed demonstrated toxicity in the mouse bioassay. Cyanotoxins (blue-green algal toxins) were identified in Florida’s surface drinking water supplies. -

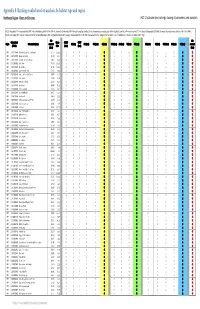

Freshwater Priority Resources

Appendix B. Ranking results based on analysis, by habitat type and region. Northwest Region ‐ Rivers and Streams HUC‐12 sub‐watershed rankings, showing all parameters used in analysis. ACCESS = Accessibility; RT = Recreational Trails; GFBWT = Great Florida Birding & Wildlife Trail; POP = Population w/in 50‐mile radius; FHO = Fishing & Hunting Opportunities; SE = Socio‐Economic Importance (category); WSM = Weighted Stream Miles; AFA = Avian Focus Areas; TE = Threatened, Endangered, & SGCN Wildlife Occurence (Freshwater Forested Wetlands); FW = Fish & Wildlife Populations (category); RFB = Riparian ‐ Freshwater Buffer; IW = Impaired Waterbodies; WRD = Weighted Road Density; IAP = Category 1 Invasive Aquatic Plants; ME ‐ FWF = Management Emphasis (category); Priority Ranks: 1 = Low; 2 = Medium Low; 3 = Medium; 4 = Medium High; 5 = High Sub- Sub- Sub-watershed Stream ACCESS GFBWT Region Sub-watershed (Name) watershed RT (Rank) POP (Rank) FHO (Rank) SE (Rank) WSM (Rank) AFA (Rank) TE (Rank) FW (Rank) RFB (Rank) IW (Rank) WRD (Rank) IAP (Rank) ME (Rank) watershed (HUC-12) Miles (Rank) (Rank) (Acres) (Rank) NW 031300110804 East River-Apalachicola River Frontal 39,713 169.61 3451 5 5 55 4 5 23254 5 NW 031300130504 Blounts Bay Frontal 25,504 81.33 4451 5 5 34 3 5 43224 5 NW 031300130503 Tates Hell Swamp-Cash Creek 20,453 80.20 4252 5 5 33 2 4 52225 5 NW 031403050602 White River 38,530 152.09 3155 5 5 51 5 4 33424 5 NW 031300110803 Brothers River 45,705 139.31 4352 5 5 52 4 5 21243 5 NW 031200011003 Lower St. Marks River 27,372 79.83 3312 5 4 35