Enterprise and Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

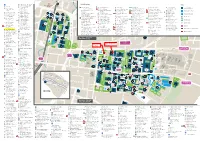

Accommodation Map

The University of Manchester Accommodation Map OXFORD S Key - Alphabetical Order CITY CENTRE Accommodation Office & Lambert Hall 33 FAIRFIELD STREET Manchester Student Homes 1 T WHITWORTH ST Linton House 20 33 LO PICCADILLY WHITWORTH STCAMBRIDGE W ROW GRANBY N Allen Hall 2 S DO STATION Manchester Aquatics Centre 42 AC T TREE K 6 N ROAD ES S V RL PR CHA ILLE Armitage Sports Centre 11 IN 7 Moberly Hall 23 CE 32 STREET S T SS S T Ashburne Hall & Sheavyn House 3 Oak House 25 A Y A Bowden Court 14 ANCUNIAN W R Opal Hall 27 M D 21 W OX T CAM REE I 40 ST C OR K Brian Redhead Court 40 OSVEN Opal Gardens 41 B GR U G RIDGE S R E 13 E PP N Broomcroft House 24 S Owens Park 26 JA 27 F T H CK 14 T REET H S Canterbury Court 4 ON C E Richmond Park & the Firs Villa 37 ORD42 ROAD15 R R E IG E Chandos Hall 6 S ST Ronson Hall 15 E HER TH H NT O ST Y BO D B ICK E ROAD Dalton-Ellis Hall & Sutherland 10 W NSW St. Anselm Hall 28 CAM S ST TH ROOBRU EET OO T TR B B L S B L O & Pankhurst Court ONSA RID O B U 1 St. Gabriel’s Hall 29 ND ST K G C C A E Grafton House 39 S R NSWI K Y L Sugden Sports Centre 21 T BRU R K P EET A N OR Grosvenor Place 13 E S Vaughan House 35 35 PL LLO 23 T & Grosvenor Street Building T YMOU Y EE T Weston Hall 7 D 39 R ROAD ST N S O Hardy Farm Residence 16 36 FT R T RA . -

Manchester Hospitals Arts Project

Administration Blood test Lecture theatre Genetic clinic Pharmacy Ante natal Gynaecology clinic wards Medical records Children's ward dept Medical genetics Arts centre MANCHESTER HOSPITALS' ARTS PROJECT BY PETER COLES Manchester Hospitals' Arts Project by Peter Coles Published by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, London, 1981 Further copies of this publication are available from the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation © 1981 Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation 98 Portland Place London WIN 4ET Telephone 01-636 5313/7 ISBN O 903319 22 5 Cover design by Michael Carney Associates Produced by PPR Printing London Wl Contents Acknowledgements 4 Foreword 5 North Western Regional Health Authority—Structure Plan 7 Manchester Hospitals' Arts Project—The Arts Team 8 Chapter 1 Setting the Scene 9 Chapter 2 How the Hospital acquired an artist 23 Chapter 3 The First Arts Team 32 Chapter 4 The Second Arts Team 43 Chapter 5 Funding and Administration 50 Chapter 6 New developments in hospital art 61 Guidelines for a hospital arts project 65 Appendices I Programme of activities from April 1980 to April 1981 66 II Summary of replies to a questionnaire sent to the 216 Health Districts in England and Wales by Julie Turner, 1980 76 Glossary 79 Photograph captions 80 Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to all those people involved with the Project, either as participants or as 'consumers' who gave up their time to talk to me. In particular, I would like to thank Mrs Jean Fowler for her kindness in allowing me to stay in the doctors' residence when necessary. I owe a great debt to Sheila Senior not only for her continued hospitality and wonderful cooking, but also for her valuable comments and secretarial help. -

Davenport Green to Ardwick

High Speed Two Phase 2b ww.hs2.org.uk October 2018 Working Draft Environmental Statement High Speed Rail (Crewe to Manchester and West Midlands to Leeds) Working Draft Environmental Statement Volume 2: Community Area report | Volume 2 | MA07 MA07: Davenport Green to Ardwick High Speed Two (HS2) Limited Two Snowhill, Snow Hill Queensway, Birmingham B4 6GA Freephone: 08081 434 434 Minicom: 08081 456 472 Email: [email protected] H10 hs2.org.uk October 2018 High Speed Rail (Crewe to Manchester and West Midlands to Leeds) Working Draft Environmental Statement Volume 2: Community Area report MA07: Davenport Green to Ardwick H10 hs2.org.uk High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has been tasked by the Department for Transport (DfT) with managing the delivery of a new national high speed rail network. It is a non-departmental public body wholly owned by the DfT. High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, Two Snowhill Snow Hill Queensway Birmingham B4 6GA Telephone: 08081 434 434 General email enquiries: [email protected] Website: www.hs2.org.uk A report prepared for High Speed Two (HS2) Limited: High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has actively considered the needs of blind and partially sighted people in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the HS2 website. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard please contact High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. © High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, 2018, except where otherwise stated. Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. -

Welcome to Your New Home

WELCOME TO YOUR NEW HOME Owens Park The information in this booklet is designed to help answer some essential questions you may have before your arrival at University Residences. *The information provided in this booklet is correct at the time of writing, however may be subject to change So you’re moving in – what next? Just over 450 people work within the residences here at the University of Manchester who will all help to settle you in and make sure your life in hall runs smoothly. Staff will be on site during our main arrival days in September, please feel free to ask for any assistance you may require. Please also refer to the online Residences Guide for more detailed information. Contact Details Address: Reception, Owens Park, Fallowfield, 293 Wilmslow Road, Manchester, M14 6HD Reception Number: 0161 306 9900 Email: [email protected] Reception is located in Owens Park and is open 24hrs a day. The Central Administration team are also located at reception and are available Monday – Friday 0900hrs – 1700hrs Finding your way to Owens Park By Air: Manchester Airport is approximately 8 miles to the south of the city, a taxi typically costs around £15- £20 to the Hall. Buses and rail shuttle service also run into Manchester city centre. By Car: Manchester is situated in the heart of the North West of England and has superb road networks into the city centre. By Coach: Chorlton Street bus station is approximately 4 miles to Owens Park, a taxi typically costs £9 - £12 By Rail: Piccadilly train station is approximately 4 miles to Owens Park, a taxi typically costs £9 - £12. -

Rusholme Calendar Phil Barton.Pdf

CALENDAR 2017 CALENDAR RUSHOLME RUSHOLME Rusholme greening projects in projects greening TREASURES OF RUSHOLME OF TREASURES will go to community to go will E V I T A E R C C 100% of purchase price purchase of 100% TREASURES OF RUSHOLME & VICTORIA PARK 2017 How many of the buildings and scenes in the Treasures of Rusholme Calendar did you recognise? We are proud of our heritage and of our vibrant present and hope that the calender has encouraged you to look anew at our wonderful neighbourhood. There is so much to see and do in Rusholme! This calendar has been produced by Creative Rusholme as part of our mission to raise the profile of our community and to develop the huge cultural potential of our neighbourhood on Manchester’s Southern Corridor. With two galleries, three parks, a major conservation area, residents from all over the world, including many thousands of young people and on a major transport route to the hospitals, universities and through to the city centre, Rusholme has it all! And we’d like everyone to know it. All aspects of the calendar have been provided free of charge. Based on an original idea by local resident Elaine Bishop, local artist and photographer Phil Barton took all the photographs and put the calendar together. Copyright for all images and text rest is retained by Phil Barton ©2016 and you should contact him if you wish to purchase or use any image [email protected]. The design and printing of the calendar has been undertaken free of charge by Scott Dawson Advertising (www.scottdawson.co.uk) as part of their commitment to supporting community endeavour. -

CV—Alpesh K. Patel/ Page 1 of 6

ALPESH KANTILAL PATEL CURRICULUM VITAE EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER, Manchester, England PhD in ART HISTORY AND VISUAL STUDIES, April 2009 Dissertation: “Queer Desi Visual Culture across the Brown Atlantic (US/UK)” MPHIL in DRAMA/SCREEN STUDIES (upgraded to PHD in 2006) YALE UNIVERSITY, New Haven, Connecticut BA in HISTORY OF ART with distinction in major, September 1997 ACADEMIC POSITIONS FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY, Miami, FL Assistant Professor of Contemporary Art and Theory, August 2011-present Director, Master in Fine Arts in Visual Arts, July 2012-present NEW YORK UNIVERSITY, New York, NY, Fall 2010-Spring 2011 Visiting Scholar, Center for Study of Gender and Sexuality FELLOWSHIPS, SCHOLARSHIPS, BURSARIES, STUDENTSHIPS, GRANTS, AND OTHER HONORS NATIONAL ENDOWMENT OF ARTS SUMMER INSTITUTE: Re-envisioning American Art History: Asian American Art, Research, and Teaching at Asian/Pacific/American Institute at New York University, July 2012 CITY OF MIAMI BEACH CULTURAL ARTS COUNCIL, Junior Anchor Grant to develop year-round programming for Miami Beach Urban Studios (MBUS), October 2012. $30,000 with matching grant FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY, Office of Engaged Creativity Grant, 2011-12 COLLEGE ART ASSOCIATION (CAA), Professional Development Fellowship, finalist, 2008 HIGHER EDUCATION FUNDING COUNCIL FOR ENGLAND (HEFCE), Overseas Research Studentship, 2006-8 UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER SCHOOL OF ARTS, HISTORIES AND CULTURES Skills Awareness for Graduate Education (SAGE) grant, to fund organization of postgraduate conference, -

Building List

ST ANDRE W’S ST T S S I V A TR HOYLE STREE ST D T SHEFFIEL T REE ST K STREET C D L DO E D PA IRFI BA FA RIN G ST REE T N EE GR Manchester Piccadilly K Station D DWIC A 35 Cordingley Lecture AR Theatre 147 78 Academy BUILDING LIST KEY 86 Core Technology bus stop BE R RY ST 37 Access Summit Facility Assessment Centre at 42 Cosmo Rodewald 122 1 Sackville Street 19 Masdar Building 39 Kilburn Building 57 Student Services 72 Vaughan House 90 National Graphene Institute The University of cluster Campus buildings Concert Hall Building (Graphene Engineering 40 Information Centre 73 Avila House RC Chaplaincy 91 McDougall Centre Manchester 01 Council Chamber 7 James Lighthill Building Innovation Centre) Technology Building 58 Christie Building 92 Jean McFarlane Building 74 Holy Name Church University residences 83 Accommodation Office 20 Ferranti6 Building 59 Simon Building (Sackville Street) ET 41 Dental Hospital 93 George Kenyon Building E 8 Renold Building A 75 AV Hill Building 15 cluster 07 Aerospace Research TR 21 MSST Tower 51 Council Chamber S E 60 Zochonis Building and Hall of Residence 9 Barnes Wallis Building / E 42 Martin Harris Centre 76 AQA Under construction Centre (UMARI) 22 SugdenR Sports Centre OA D cluster (Whitworth Building) ELD T forR Music and Drama 61 Chemistry Building 100 Denmark Road Hall FI S SON FSE Student Hub / cluster DE cluster 63 Alan Gilbert IR cluster G WA 77 Ellen Wilkinson Building cluster IN26 Booth Street East Building 68 Council Chamber N T 62 Dryden Street Nursery 121 Liberty Park FA W 43 Coupland Building -

10Th Anniversary Tile 7 71 1909 Pottery 9 42 1914 Pottery 14 103 1915 in Print 15 64 1917 at Pilkington’S (Inc

10th Anniversary tile 7 71 1909 pottery 9 42 1914 pottery 14 103 1915 in print 15 64 1917 at Pilkington’s (inc. South America) 17 61 1950’s images 17 12 1950s - An account of pottery production at Pilkington’s in the 1950s (2005) 5 (single document) 1950s pottery 19 77 Aberystwyth – A collection in its time 5 64 Advertisement 1907 17 13 Advertisement 1913, 1906, 1926 & reprint of leaflet “Throwing of Modern Pottery” 2 10, 44, 56, 105, 51 Advertisement style 1904-1938 1 1, 104 Advertisements 13 125 Advertising – and research request 9 3 Advertising Oddity 12 121 Agate bowls 19 96 Albion United Reform Church Memorial and colour page 2 1 41 American Pottery Gazette – Arthur Veel Rose, Kakiemon designs by William Burton 19 40,65,69 Animal figures - stand alone document July 2004 & additional information 4 39 Antiques Roadshow: An insider’s view by Will Farmer 20 76 Antiques Roadshow: The ‘Cole’ charger at Compton Verney 20 73 APG, The American Pottery Gazette 20 61, 85 Art schools and the artists 13 98 Arts & Crafts Exhibition Paris 1914 14 71 Arts and Crafts Exhibition at the Grosvenor Gallery 1913 13 6 Auction - historic auction prices 16 36, 70 Auctions - historic auction prices 14 85 Auctions - historic auction prices 15 12 Auctions: Ebay 2019 19 95 Auctions: Ebay 2020 20 78 Auctions: Fieldings Decades of Design 15 October 2020 20 112 Auctions: Harriman Judd 2001 20 46 Auctions: Kingham & Orme Nov 2017, May 2018 18 30, 62 Auctions: Kingham & Orme, February, 2019 19 52, 53, 97, Auctions: Lyon & Turnbull April 2019 19 53 Auctions: Lyon & Turnbull Oct 2018 – The Contents of Kirkton House 18 105 Auctions: Woolley & Wallis Arts & Crafts Design 6 October 2020 20 108 Auctions: Woolley & Wallis Dec 2017, Jun 2018 18 31, 89 Auctions: Woolley & Wallis December 2018, June 2019 19 51 Auctions: Woolley & Wallis, 25 Feb 2015, Nick Rocke Collection 15 22, 26 Back Issues 9 31 Barlow A.E. -

2001: University of Manchester

CLASSICAL ASSOCIATION ANNUAL CONFERENCE THE UNIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER WEDNESDAY 18 APRIL - SATURDAY 21 APRIL 2001 CA 2001 CONFERENCE INFORMATION The CA Conference in 2001 will be hosted by the University of Manchester, and will form part of the celebrations of the 150th anniversary of the University, which was originally founded as Owens College in 1851 and became the first of England’s great civic universities. Programme CA 2001 offers a programme of exceptional variety. Several panels will focus on the theme of ‘setting the agenda for the twenty-first century’, as advertised in the Call for Papers: ‘Computers and the Classicist’; ‘Classics without Greek and Latin: the future for teaching and research’; ‘Shifting Boundaries: Classics and other disciplines’; ‘Plato after Plato’; ‘Personal Identity’; ‘Fragments’; ‘Ancient Ideas of Freedom’. In addition panels will be offered on: § Semiotics and Greek Literature § The History of Classics § Poetic Identity § Ancient Music § Old Age § Folklore § Romanisation and Other Interactions § Ancient Religion § Late Ovid § Greek Tragedy As you can see from the enclosed programme, our three plenary sessions with distinguished guest speakers will also address some of the highlighted themes. They include the Presidential Address by Professor T.P. Wiseman. In addition, this year, there will be a performance of Lyric Poetry in Greek and Latin. A welcoming reception will be held on Wednesday, 18 April, in the newly refurbished galleries of the Manchester Museum. The main Conference Centre, where all other scheduled events will take place, is at Hulme Hall, Oxford Place, Victoria Park, Manchester M14 5RL. Accommodation for delegates will be on site at Hulme Hall and, if needed, at nearby Dalton Ellis Hall. -

Thurs 25 March Additional Programme Information 090310

From the Margins to the Core? Conference Additional Programme Information Day 2 - Thursday 25 March 2010 Connecting or Competing Equalities? 09.30-09.50 Title: Diversity and cultural policy This presentation will suggest how contemporary concerns with diversity and difference present particular challenges for mainstream art historical and curatorial practice. It will locate Dr Leon Wainwright’s own practice, which overlaps historical research, collaborations with museums and galleries, and curatorial work. Briefly, he will set out the broader intellectual background on which the concept of ‘margins and core’ has emerged in the academy, and suggest why opportunities for exploring transnationalism may also become the site of ‘competing equalities’. The examples for this range from the institutional life in Britain of World Art Studies, and two exhibitions in Liverpool in 2010. Chair: Dr Jo Littler, Senior Lecturer in Media and Cultural Studies at Middlesex University As well as being the Senior Lecturer in Media and Cultural Studies at Middlesex University, Jo Littler is co-editor, with Roshi Naidoo, of The Politics of Heritage: The Legacies of Race (Routledge 2005), author of Radical Consumption? Shopping for change in contemporary culture (Open University Press, 2009) and an associate editor of Soundings. Speaker: Dr Leon Wainwright, Senior Lecturer in History, Art & Design, Manchester Metropolitan University Leon Wainwright is Senior Lecturer in the History of Art and Design at Manchester Metropolitan University, Visiting Fellow at the Yale Center for British Art, a member of the editorial board of the journal Third Text, and Guest Curator, with Reyahn King, of Aubrey Williams Atlantic Fire (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, 2010). -

Building Key Key P

T S BAR ING S D TREET N L EE E R I G F K R IC I D W 35 Cordingley Lecture Theatre A RD A F 147 Building key A Key 86 Core Technology Facility Manchester Piccadilly Bus 78 Academy Station stop B 42 Cosmo Rodewald ERRY S cluster 63 Alan Gilbert 47 Coupland Building 3 83 Grove House 16 Manchester 53 Roscoe Building 81 The Manchester 32 Access Summit Concert Hall T Campus buildings Learning Commons 31 Crawford House 29 Harold Hankins Building Interdisciplinary Biocentre 45 Rutherford Building Incubator Building Disability Resource 01 Council Chamber cluster 46 Alan Turing Building 33 Crawford House Lecture 74 Holy Name Church 44 Manchester Museum cluster 14 The Mill Centre (Sackville Street) 01 Sackville Street Building University residences Theatres 76 AQA 80 Horniman House cluster 65 Mansfield Cooper Building 67 Samuel Alexander Building 37 University Place 37 Accommodation Office 51 Council Chamber cluster (Whitworth Building) 3 10 36 Arthur Lewis Building 867 Denmark Building 35 Humanities Bridgeford 42 Martin Harris Centre for 56 Schunck Building 38 Waterloo Place 31 Accounting and Finance A cluster cluster Principal car parks 6 15 P 68 Council Chamber 75 AV Hill Building T 41 Dental School and Hospital Street Music and Drama 11 Weston Hall 01 Aerospace Research E 54 Schuster Building (Students’ Union) E 30 Devonshire House AD 40 Information Technology 25 Materials Science Centre Centre (UMARI) 73 Avila House RC ChaplaTinRcy RO 59 Simon Building 84 Whitworth Art PC clusters S SON cluster 31 Counselling Service 2 G 70 Dover Street BuildWinAg -

143 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

143 bus time schedule & line map 143 Manchester - West Didsbury View In Website Mode The 143 bus line (Manchester - West Didsbury) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Piccadilly Gardens: 7:30 AM - 11:39 PM (2) West Didsbury: 7:13 AM - 11:59 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 143 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 143 bus arriving. Direction: Piccadilly Gardens 143 bus Time Schedule 24 stops Piccadilly Gardens Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 9:20 AM - 7:42 PM Monday 7:30 AM - 11:39 PM Palatine Road, West Didsbury Tuesday 7:30 AM - 11:39 PM The Christie Wednesday 7:30 AM - 11:39 PM Palatine Road, the Christie Thursday 7:30 AM - 11:39 PM Wilmslow Road, Withington Friday 7:30 AM - 11:39 PM Withington Library, Withington Saturday 9:25 AM - 11:41 PM 1c 160-164 Wellington Road, Manchester Victoria Road, Fallowƒeld Wilmslow Road, Manchester 143 bus Info Granville Road, Fallowƒeld Direction: Piccadilly Gardens 340 Wilmslow Road, Manchester Stops: 24 Trip Duration: 34 min Friendship Inn, Fallowƒeld Line Summary: Palatine Road, West Didsbury, The Christie, Palatine Road, the Christie, Wilmslow Road, Cawdor Road, Owens Park Withington, Withington Library, Withington, Victoria 2 Cawdor Road, Manchester Road, Fallowƒeld, Granville Road, Fallowƒeld, Friendship Inn, Fallowƒeld, Cawdor Road, Owens Langley Road, Owens Park Park, Langley Road, Owens Park, Grangethorpe Road, Owens Park, Platt Lane, Rusholme, Rusholme Grangethorpe Road, Owens Park Centre, Rusholme, Great Western Street, Rusholme,