Cognitive Development Society VI Biennial Meeting October 16-17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finalist Symposium

TEMPLETON SCIENCE OF PROSPECTION AWARDS The Prospective Psychology Project University of Pennsylvania Positive Psychology Center FINALIST SYMPOSIUM: AUGUST 4–5, 201 4 37 01 Market Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 191 04 www.ppc.sas.upenn.edu Special Thanks to The John Templeton Foundation TEMPLETON SCIENCE OF PROSPECTION AWARDS Table of Contents Sponsors ...............................................1 Science of Prospection Steering Committee ..........2 Symposium Agenda Overview ........................6 Day One Presentation Schedule ......................8 Day Two Presentation Schedule .....................10 Science of Prospection Proposal Abstracts ...........12 SPONSORS The Prospective Psychology Project Some of the goals of Positive Psychology are to build a science that supports: Supported by a grant from the John Templeton • Families and schools that allow children to flourish Foundation, the University of Pennsylvania Positive • Workplaces that foster satisfaction and high Psychology Center has established the Prospective productivity Psychology Project to advance the scientific understanding of prospection, or the mental • Communities that encourage civic engagement representation of possible futures. To foster this • Therapists who identify and nurture their patients’ new field of research, the Prospective Psychology strengths Project announced the Templeton Science of • The teaching of Positive Psychology Prospection Awards competition in 2013. The awards will encourage research aimed at understanding • Dissemination of -

A Qualitative Study of Falling in Love

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1988 It happened by "magic": A qualitative study of falling in love Jacqueline L. Gibson The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Gibson, Jacqueline L., "It happened by "magic": A qualitative study of falling in love" (1988). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4975. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4975 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 Th is is an unpublished manuscript in which copyright s u b s i s t s , Any further r e p r in t in g of it s contents must be APPROVED BY THE AUTHOR. Ma n sf ie l d Library Un iv e r s it y of Montana ' Date :____1 9 . 8 J B _______ IT HAPPENED BY "MAGIC": A QUALITATIVE STUDY OF FALLING IN LOVE By Jacqueline L. Gibson B. A., University of Montana, Missoula, 1975 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts University of Montana 1988 Approved by Chairman, Board of Examiners UMI Number: E P 40439 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Science of Adolescent Learning: How Identity and Empowerment Influence Student Learning August 2019

Science of Adolescent Learning: How Identity and Empowerment Influence Student Learning August 2019 SCIENCE OF ADOLESCENT LEARNING Acknowledgments This report was written by Hans Hermann, policy and research associate at the Alliance for Excellent Education (All4Ed). Robyn Harper, policy and research associate at All4Ed, contributed to the report. Winsome Waite, PhD, vice president of practice at All4Ed, leads All4Ed’s Science of Adolescent Learning initiative and also contributed to this report. Kristen Loschert, editorial director at All4Ed, supported the development of this report and series. Cover photo by Lorie Shaull via Wikimedia Commons. Photo cropped to fit cover dimensions. All4Ed thanks the following individuals for their guidance and input during the development of this report: Adriana Galván, PhD, University of California–Los Angeles; Ben Kirshner, PhD, University of Colorado–Boulder; and Laurence Steinberg, PhD, Temple University. All4Ed also acknowledges David Osher, PhD, vice president and institute fellow at the American Institutes for Research, for his support as a lead advisor in the development of this report series. The Alliance for Excellent Education (All4Ed) is a Washington, DC–based national policy, practice, and advocacy organization dedicated to ensuring that all students, particularly those underperforming and those historically underserved, graduate from high school ready for success in college, work, and citizenship. all4ed.org © Alliance for Excellent Education, 2019. @All4Ed facebook.com/All4ed Science of Adolescent Learning: How Identity and Empowerment Influence Student Learning | all4ed.org Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................1 About All4Ed’s SAL Consensus Statement Report Series . .2 All4Ed’s SAL Research Consensus Statements ..............................3 How Identity and Empowerment Influence Student Learning. -

Mapping Mind-Brain Development: Towards a Comprehensive Theory

Journal of Intelligence Review Mapping Mind-Brain Development: Towards a Comprehensive Theory George Spanoudis 1,* and Andreas Demetriou 2,3 1 Psychology Department, University of Cyprus, 1678 Nicosia, Cyprus 2 Department of Psychology, University of Nicosia, 1700 Nicosia, Cyprus; [email protected] 3 Cyprus Academy of Science, Letters, and Arts, 1700 Nicosia, Cyprus * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +357-22892969 Received: 20 January 2020; Accepted: 20 April 2020; Published: 26 April 2020 Abstract: The relations between the developing mind and developing brain are explored. We outline a theory of intellectual development postulating that the mind comprises four systems of processes (domain-specific, attention and working memory, reasoning, and cognizance) developing in four cycles (episodic, realistic, rule-based, and principle-based representations, emerging at birth, 2, 6, and 11 years, respectively), with two phases in each. Changes in reasoning relate to processing efficiency in the first phase and working memory in the second phase. Awareness of mental processes is recycled with the changes in each cycle and drives their integration into the representational unit of the next cycle. Brain research shows that each type of processes is served by specialized brain networks. Domain-specific processes are rooted in sensory cortices; working memory processes are mainly rooted in hippocampal, parietal, and prefrontal cortices; abstraction and alignment processes are rooted in parietal, frontal, and prefrontal and medial cortices. Information entering these networks is available to awareness processes. Brain networks change along the four cycles, in precision, connectivity, and brain rhythms. Principles of mind-brain interaction are discussed. Keywords: brain; mind; development; intelligence; mental and brain changes; brain networks 1. -

The Orange Spiel Page 1 March 2020

The Orange Spiel Page 1 March 2020 Volume 40 Issue 3 March 2020 We meet at 7:00 most Thursdays at Shepherd of the Woods Lutheran, 7860 Southside Blvd, Jacksonville, FL Guests always welcome Call 355-SING No Experience Necessary WHAT'S INSIDE SINGING VALENTINES Title Page A GREAT SUCCESS Singing Valentines A Great Success 1, 3-4 by Mike Sobolewski Editorial 2 Magic Choral Trick #383 #381 5-6 he Big Orange Chorus just completed another Reframing Right And Wrong 6 successful Singing Valentine’s Day. The Chorus 4 Ways To Connect With Your Audience 7 delivered 73 singing valentines over a 4 day pe- Jaguars Award Us 7 T riod. The chorus grossed almost $6,000 and How To Sing Better Right Now 8-9 netted just under $5,000. A very special thanks goes to 2 Causes Of Vocal Hoarseness 9-10 Jan Sobolewski and Helen Giallombardo for manning What Does Science Say About The 11-13 Valentine Central on Friday, February 14. They solved Chapter Quartets 13 several problems that arose and actually took several Free Your Voice 14 valentine orders which were given to the quartets. Free Singing Tips 14 Quartet Corner 15 Of course special thanks goes to all the members who Chapter Member Stats 15 participated in delivering these special memories to our How To Become A Better Singer 16 customers. Here is a listing: Upcoming Schedules 17 • Wednesday : Mark Roblez, Steve Mullens, Jason Birthdays / Guests / New Members 17 Dearing, Mike Sobolewski Directing Team / Other Leaders 18 • Thursday : Dillon Tidwell, Steve Mullens / Eric Chapter Officers / Music Team 19 Grimes, Ryan Feeney, Rick Ard • Friday : 1. -

Make It New: Reshaping Jazz in the 21St Century

Make It New RESHAPING JAZZ IN THE 21ST CENTURY Bill Beuttler Copyright © 2019 by Bill Beuttler Lever Press (leverpress.org) is a publisher of pathbreaking scholarship. Supported by a consortium of liberal arts institutions focused on, and renowned for, excellence in both research and teaching, our press is grounded on three essential commitments: to be a digitally native press, to be a peer- reviewed, open access press that charges no fees to either authors or their institutions, and to be a press aligned with the ethos and mission of liberal arts colleges. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.11469938 Print ISBN: 978-1-64315-005- 5 Open access ISBN: 978-1-64315-006- 2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944840 Published in the United States of America by Lever Press, in partnership with Amherst College Press and Michigan Publishing Contents Member Institution Acknowledgments xi Introduction 1 1. Jason Moran 21 2. Vijay Iyer 53 3. Rudresh Mahanthappa 93 4. The Bad Plus 117 5. Miguel Zenón 155 6. Anat Cohen 181 7. Robert Glasper 203 8. Esperanza Spalding 231 Epilogue 259 Interview Sources 271 Notes 277 Acknowledgments 291 Member Institution Acknowledgments Lever Press is a joint venture. This work was made possible by the generous sup- port of -

Total Tracks Number: 2218 Total Tracks Length: 151:00:00 Total Tracks Size: 16.0 GB

Total tracks number: 2218 Total tracks length: 151:00:00 Total tracks size: 16.0 GB # Artist Title Length 01 2 Brothers On The 4Th Floor Can't Help Myself 05:39 02 2 Brothers On The 4th Floor Dreams (Will Come Alive) 04:19 03 2 Brothers on the 4th Floor I'm Thinking of You 03:24 04 2 Brothers On The 4Th Floor Never Alone 04:10 05 2 Brothers On The 4th Floor There's A Key 03:54 06 2 Eivissa Oh La La 04:41 07 2 In a Room Wiggle It 03:59 08 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This 03:40 09 2 Unlimited Jump For Joy 03:39 10 2 Unlimited No Limit 03:28 11 2 Unlimited No One 03:24 12 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone 05:36 13 2 Unlimited Workaholic 03:33 14 2pac Thug Mansion 03:32 15 2pac Wonder If Heaven Got A Ghetto 04:34 16 2pac Daz Kurupt Baby Dont Cry Remix 05:20 17 Three Doors Down Be Like That 04:25 18 3 Doors Down Here Without You 03:53 19 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 03:52 20 3lw No More (Baby I'm Gonna Do Rig 04:17 21 3lw Playa Gonna Play 03:06 22 3rd Eye Blind How Is It Gonna Be 04:10 23 3T Anything 04:15 24 4 Non Blondes What's Up 04:55 25 4 Non Blonds What's Up? 04:09 26 38 Special Caught Up In You 04:25 27 38 Special Hold On Loosely 04:40 28 38 Special Second Chance 04:12 29 50 Cent In Da Club 03:42 30 50 cent Window Shopper 03:09 31 98 Degrees Give Me One More Night (Una No 03:23 32 98 Degrees I Do (Cherish You) 03:43 33 98 Degrees Invisible Man 04:38 34 98 Degrees My Everything 04:28 35 98 Degrees The Hardest Thing 04:27 36 112 Anywhere 04:03 37 112 Cupid 04:07 38 112 Dance With Me 03:41 39 112 Love You Like I Did 04:16 40 702 Where My Girls At 02:44 -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Steve Ripley a Rock and Roll Legend in Our Own Backyard Who Has Worked with Some of the Greats

Steve Ripley A rock and roll legend in our own backyard who has worked with some of the greats. Chapter 01 – 1:10 Introduction Announcer: Steve Ripley grew up in Oklahoma, graduating from Glencoe High School and Oklahoma State University. He went on to become a recording artist, record producer, songwriter, studio engineer, guitarist and inventor. Steve worked with Bob Dylan, playing guitar on the Shot of Love album and on the Shot of Love tour. Dylan listed Ripley as one of the good guitarists he had played with. Red Dirt was first used by Steve Ripley’s band Moses when the group chose the label name Red Dirt Records. Steve founded Ripley Guitars in Burbank, California, creating guitars for musicians like Jimmy Buffet, J.J. Cale and Eddie Van Halen. In 1987 Steve moved to Tulsa to buy Leon Russell’s recording facility The Church Studio. Steve formed the country band The Tractors and was the co-writer of the country hit “Baby Likes to Rock It”. Under his own record label, Boy Rocking Records, Steve produced artists such as The Tractors, Leon Russell and the Red Dirt Rangers. What you are about to hear is a segment from Steve Ripley’s yet-to-be-posted oral history interview, but we wanted you to hear these chapters as he talks about his relationship with Bob Dylan, dining with the Beatles and his friendship with Leon Russell, on VoicesofOklahoma.com. Chapter 02 – 10:45 Concept of the Tractors John Erling: Today’s date, April 17, 2018. And we’re in your recording studio. -

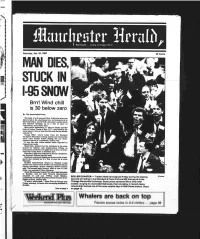

MAN Hea STUCK in I458N0W

iianritpBlpr) Manchester — A City of Village Charm Hpralft Saturday, Jan. 24,1987 30 Cents MAN HEa % ^3 a STUCK IN CUR I458N0W Brrr! Wind chill V is 30 below zero Bv The Associated Press The body of a 67-year-old New York state man was discovered in his snowbound car on Interstate 95 in Norwalk Friday, nearly half a day after a winter storm had finished dumping up to a foot of snow on Connecticut, state police said. State police spokesman Lt. Edward Dailey said the body of Arthur Young of Rye, N.Y., was found by his son at about 1; 30 p.m. near the Norwalk-Darien border and exit 13. Young didn’t return home from his Westport [ft workplace Thursday evening and his son retraced his usual route Friday before finding the car three- quarters buried in a snowbank, Dailey said. It was the only storm-related death reported on Connecticut roads. Meanwhile, shelters for the homeless in the state braced for bitterly cold temperatures Friday as forecasters predicted overnight lows of 10 to IS with a wind chill factor down to 30 below zero. !CIM Saturday’s high was expected to be just 15 degrees, the National Wedther Service said. Residents continued digging out from a major winter stohn that dumped up to a foot of snow on te state Thursday. Bradley International Airport in Windsor Locks opened one runway early Friday and resumed full air carrier operations, airport manager Robert Juliano said. The second main runway, used in case of wind shifts, was opening Friday afternoon. -

Paradigm Shift in Memory Development 2 August 2010

Paradigm shift in memory development 2 August 2010 (PhysOrg.com) -- A new study from UC Davis Later, outside the scanner, they were shown the challenges conventional wisdom on the pictures again, in black ink and mixed with new development of memory in children. ones. The subjects were and asked whether they had seen them before and whether they had been The prevailing view has been that changes in how red or green. memories are formed as children grow are driven by development of the prefrontal cortex, while the Younger children were less selective in using brain role of the hippocampus, a structure located in the regions in the hippocampus and the adjacent middle of the brain and known to be important for posterior parahippocampus as new memories were forming and recalling memories, is fixed in early formed, the researchers found. Older children and childhood, said Simona Ghetti, associate professor young adults became more selective and in at the UC Davis Department of Psychology and the recruiting specific areas of the hippocampus during Center for Mind and Brain. episodic memory formation. Instead, a new study by Ghetti and colleagues The discovery should open the door to more shows that between the ages of eight and 14, the research, Ghetti said. function of the hippocampus continues to change. The study was published this month in the Journal "We need to learn how the hippocampus is of Neuroscience. changing and what the implications of these changes are for the development of episodic "The development of prefrontal function is memory; we also need to know how the interaction important, but we found that the hippocampus also between the hippocampus and other relevant continues to develop," Ghetti said. -

Abstracts of the Psychonomic Society — Volume 14 — November 2009 50Th Annual Meeting — November 19–22, 2009 — Boston, Massachusetts

Abstracts of the Psychonomic Society — Volume 14 — November 2009 50th Annual Meeting — November 19–22, 2009 — Boston, Massachusetts Papers 1–7 Friday Morning Scene Processing randomly positioned. When targets were systematically located within Grand Ballroom, Friday Morning, 8:00–9:35 scenes, search for them became progressively more efficient. Learning was abstracted away from bedrooms and transferred to a living room, Chaired by Carrick C. Williams, Mississippi State University where the target was on a sofa pillow. These contingencies were explicit and led to central tendency biases in memory for precise target positions. 8:00–8:15 (1) These results broaden the scope of conditions under which contextual Encoding and Visual Memory: Is Task Always Irrelevant? CAR- cuing operates and demonstrate for the first time that semantic memory RICK C. WILLIAMS, Mississippi State University—Although some plays a causal and independent role in the learning of associations be- aspects of encoding (e.g., presentation time) appear to have an effect tween objects in real-world scenes. on visual memories, viewing task (incidental or intentional encoding) does not. The present study investigated whether different encoding 9:20–9:35 (5) manipulations would impact visual memories equally for all objects Visual Memory: Confidence, Accuracy, and Recollection of Specific in a conjunction search (e.g., targets, color distractors, object category Details. GEOFFREY R. LOFTUS, University of Washington, MARK T. distractors, or distractors unrelated to the target).