PDF Download Under a Creative Commons CC-BY License

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pagan Survivals, Superstitions and Popular Cultures in Early Medieval Pastoral Literature

Bernadette Filotas PAGAN SURVIVALS, SUPERSTITIONS AND POPULAR CULTURES IN EARLY MEDIEVAL PASTORAL LITERATURE Is medieval pastoral literature an accurate reflection of actual beliefs and practices in the early medieval West or simply of literary conventions in- herited by clerical writers? How and to what extent did Christianity and traditional pre-Christian beliefs and practices come into conflict, influence each other, and merge in popular culture? This comprehensive study examines early medieval popular culture as it appears in ecclesiastical and secular law, sermons, penitentials and other pastoral works – a selective, skewed, but still illuminating record of the be- liefs and practices of ordinary Christians. Concentrating on the five cen- turies from c. 500 to c. 1000, Pagan Survivals, Superstitions and Popular Cultures in Early Medieval Pastoral Literature presents the evidence for folk religious beliefs and piety, attitudes to nature and death, festivals, magic, drinking and alimentary customs. As such it provides a precious glimpse of the mu- tual adaptation of Christianity and traditional cultures at an important period of cultural and religious transition. Studies and Texts 151 Pagan Survivals, Superstitions and Popular Cultures in Early Medieval Pastoral Literature by Bernadette Filotas Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Aid to Scholarly Publications Programme, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION Filotas, Bernadette, 1941- Pagan survivals, superstitions and popular cultures in early medieval pastoral literature / by Bernadette Filotas. -

Why We Play: an Anthropological Study (Enlarged Edition)

ROBERTE HAMAYON WHY WE PLAY An Anthropological Study translated by damien simon foreword by michael puett ON KINGS DAVID GRAEBER & MARSHALL SAHLINS WHY WE PLAY Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Troop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com WHY WE PLAY AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY Roberte Hamayon Enlarged Edition Translated by Damien Simon Foreword by Michael Puett Hau Books Chicago English Translation © 2016 Hau Books and Roberte Hamayon Original French Edition, Jouer: Une Étude Anthropologique, © 2012 Éditions La Découverte Cover Image: Detail of M. C. Escher’s (1898–1972), “Te Encounter,” © May 1944, 13 7/16 x 18 5/16 in. (34.1 x 46.5 cm) sheet: 16 x 21 7/8 in. (40.6 x 55.6 cm), Lithograph. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9861325-6-8 LCCN: 2016902726 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by Te University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. Table of Contents Acknowledgments xiii Foreword: “In praise of play” by Michael Puett xv Introduction: “Playing”: A bundle of paradoxes 1 Chronicle of evidence 2 Outline of my approach 6 PART I: FROM GAMES TO PLAY 1. Can play be an object of research? 13 Contemporary anthropology’s curious lack of interest 15 Upstream and downstream 18 Transversal notions 18 First axis: Sport as a regulated activity 18 Second axis: Ritual as an interactional structure 20 Toward cognitive studies 23 From child psychology as a cognitive structure 24 . -

Larry Page Developing the Largest Corporate Foundation in Every Successful Company Must Face: As Google Word.” the United States

LOWE —continued from front flap— Praise for $19.95 USA/$23.95 CAN In addition to examining Google’s breakthrough business strategies and new business models— In many ways, Google is the prototype of a which have transformed online advertising G and changed the way we look at corporate successful twenty-fi rst-century company. It uses responsibility and employee relations——Lowe Google technology in new ways to make information universally accessible; promotes a corporate explains why Google may be a harbinger of o 5]]UZS SPEAKS culture that encourages creativity among its where corporate America is headed. She also A>3/9A addresses controversies surrounding Google, such o employees; and takes its role as a corporate citizen as copyright infringement, antitrust concerns, and “It’s not hard to see that Google is a phenomenal company....At Secrets of the World’s Greatest Billionaire Entrepreneurs, very seriously, investing in green initiatives and personal privacy and poses the question almost Geico, we pay these guys a whole lot of money for this and that key g Sergey Brin and Larry Page developing the largest corporate foundation in every successful company must face: as Google word.” the United States. grows, can it hold on to its entrepreneurial spirit as —Warren Buffett l well as its informal motto, “Don’t do evil”? e Following in the footsteps of Warren Buffett “Google rocks. It raised my perceived IQ by about 20 points.” Speaks and Jack Welch Speaks——which contain a SPEAKS What started out as a university research project —Wes Boyd conversational style that successfully captures the conducted by Sergey Brin and Larry Page has President of Moveon.Org essence of these business leaders—Google Speaks ended up revolutionizing the world we live in. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season

INFANTRY HALL PROVIDENCE >©§to! Thirty-fifth Season, 1915-1916 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE TUESDAY EVENING, DECEMBER 28 AT 8.15 COPYRIGHT, 1915, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS. MANAGER ii^^i^"""" u Yes, Ifs a Steinway" ISN'T there supreme satisfaction in being able to say that of the piano in your home? Would you have the same feeling about any other piano? " It's a Steinway." Nothing more need be said. Everybody knows you have chosen wisely; you have given to your home the very best that money can buy. You will never even think of changing this piano for any other. As the years go by the words "It's a Steinway" will mean more and more to you, and thousands of times, as you continue to enjoy through life the com- panionship of that noble instrument, absolutely without a peer, you will say to yourself: "How glad I am I paid the few extr? dollars and got a Steinway." STEINWAY HALL 107-109 East 14th Street, New York Subway Express Station at the Door Represented by the Foremost Dealers Everywhere 2>ympif Thirty-fifth Season,Se 1915-1916 Dr. KARL MUC per; \l iCs\l\-A Violins. Witek, A. Roth, 0. Hoffmann, J. Rissland, K. Concert-master. Koessler, M. Schmidt, E. Theodorowicz, J. Noack, S. Mahn, F. Bak, A. Traupe, W. Goldstein, H. Tak, E. Ribarsch, A. Baraniecki, A. Sauvlet, H. Habenicht, W. Fiedler, B. Berger, H. Goldstein, S. Fiumara, P. Spoor, S. Stilzen, H. Fiedler, A. -

The Horse-Breeder's Guide and Hand Book

LIBRAKT UNIVERSITY^' PENNSYLVANIA FAIRMAN ROGERS COLLECTION ON HORSEMANSHIP (fop^ U Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2009 with funding from Lyrasis IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/horsebreedersguiOObruc TSIE HORSE-BREEDER'S GUIDE HAND BOOK. EMBRACING ONE HUNDRED TABULATED PEDIGREES OF THE PRIN- CIPAL SIRES, WITH FULL PERFORMANCES OF EACH AND BEST OF THEIR GET, COVERING THE SEASON OF 1883, WITH A FEW OF THE DISTINGUISHED DEAD ONES. By S. D. BRUCE, A.i3.th.or of tlie Ainerican. Stud Boole. PUBLISHED AT Office op TURF, FIELD AND FARM, o9 & 41 Park Row. 1883. NEW BOLTON CSNT&R Co 2, Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1883, By S. D. Bruce, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. INDEX c^ Stallions Covering in 1SS3, ^.^ WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, ALPHABETICALLY ARRANGED, PAGES 1 TO 181, INCLUSIVE. PART SECOISTD. DEAD SIRES WHOSE PEDIGREES AND PERFORMANCES, &c., ARE GIVEN IN THIS WORK, PAGES 184 TO 205, INCLUSIVE, ALPHA- BETICALLY ARRANGED. Index to Sires of Stallions described and tabulated in tliis volume. PAGE. Abd-el-Kader Sire of Algerine 5 Adventurer Blythwood 23 Alarm Himvar 75 Artillery Kyrle Daly 97 Australian Baden Baden 11 Fellowcraft 47 Han-v O'Fallon 71 Spendthrift 147 Springbok 149 Wilful 177 Wildidle 179 Beadsman Saxon 143 Bel Demonio. Fechter 45 Billet Elias Lawrence ' 37 Volturno 171 Blair Athol. Glen Athol 53 Highlander 73 Stonehege 151 Bonnie Scotland Bramble 25 Luke Blackburn 109 Plenipo 129 Boston Lexington 199 Breadalbane. Ill-Used 85 Citadel Gleuelg... -

Future-Talk, Finance, and Christian Eschatology

Trading Futures: Future-Talk, Finance, and Christian Eschatology The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:37925648 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA !"#$%&'()*+*",-.(( ( )*+*",/!#012()%&#&3,2(#&$(45"%-+%#&(6-35#+707'8( ! ! "!#$%%&'()($*+!,'&%&+(&#!! -.! /$0$,&!1)$)! 2*! 23&!/)450(.!*6!7)'8)'#!9$8$+$(.!:43**0! $+!,)'($)0!6506$00;&+(!*6!(3&!'&<5$'&;&+(%! 6*'!(3&!#&='&&!*6! 9*4(*'!*6!23&*0*=.! >+!(3&!%5?@&4(!*6! 23&*0*=.! 7)'8)'#!A+$8&'%$(.! B);?'$#=&C!1)%%)435%&((%! /&?'5)'.!DEFG! ! ! ! 23$%!H*'I!$%!0$4&+%&#!5+#&'!)!B'&)($8&!B*;;*+%!"(('$?5($*+JK*+B*;;&'4$)0J :3)'&"0$I&!LME!>+(&'+)($*+)0!N$4&+%&M!3((,%OPP4'&)($8&4*;;*+%M*'=P0$4&+%&%P?.J+4J %)PLMEP0&=)04*#&! ! ! 9$%%&'()($*+!"#8$%*'O!9'M!1).')!Q$8&')!Q$8&')!!!!!! ! ! !!!"5(3*'O!/$0$,&!1)$)!! ! ! 2')#$+=!/5(5'&%O!/5(5'&J2)0IC!/$+)+4&C!)+#!B3'$%($)+!R%43)(*0*=.! ! ! "?%(')4(! ! ! ! :()+#)'#!(&S(?**I%!#&%4'$?&!6$+)+4&!)%!(3&!6$&0#!*6!&4*+*;$4%!(3)(!4*+4&'+%! $(%&06!H$(3!(3&!65(5'&M!23$%!#$%%&'()($*+!%5==&%(%!$+%(&)#!(3)(!6$+)+4$)0!#$%4*5'%&! 4*+@5'&%!)!,)'($450)'!;*#&!*6!65(5'&J()0IC!*+&!(3)(!'&+#&'%!(3&!65(5'&!)%!%*;&3*H! ,'&#$4()?0&C!;)+)=&)?0&C!)+#!,'*6$()?0&M!23$%!;*#&!*6!$;)=$+)($*+!$+6*';%!?'*)#&'! %*4$)0C!,*0$($4)0C!)+#!(3&*0*=$4)0!#$%4*5'%&%!)+#C!$+!6)4(C!4*+%($(5(&%!)!#*;$+)+(!;*#&! -

Pioneers of Modern Geography: Translations Pertaining to German Geographers of the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries Robert C

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier GreyPlace 1990 Pioneers of Modern Geography: Translations Pertaining to German Geographers of the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries Robert C. West Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/grey Part of the Earth Sciences Commons, and the Human Geography Commons Recommended Citation West, Robert C. (1990). Pioneers of Modern Geography: Translations Pertaining to German Geographers of the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries. Baton Rouge: Department of Geography & Anthropology, Louisiana State University. Geoscience and Man, Volume 28. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in GreyPlace by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Pioneers of Modern Geography Translations Pertaining to German Geographers of the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries Translated and Edited by Robert C. West GEOSCIENCE AND MAN-VOLUME 28-1990 LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY s 62 P5213 iiiiiiiii 10438105 DATE DUE GEOSCIENCE AND MAN Volume 28 PIONEERS OF MODERN GEOGRAPHY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 https://archive.org/details/pioneersofmodern28west GEOSCIENCE & MAN SYMPOSIA, MONOGRAPHS, AND COLLECTIONS OF PAPERS IN GEOGRAPHY, ANTHROPOLOGY AND GEOLOGY PUBLISHED BY GEOSCIENCE PUBLICATIONS DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND ANTHROPOLOGY LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY VOLUME 28 PIONEERS OF MODERN GEOGRAPHY TRANSLATIONS PERTAINING TO GERMAN GEOGRAPHERS OF THE LATE NINETEENTH AND EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURIES Translated and Edited by Robert C. West BATON ROUGE 1990 Property of the LfhraTy Wilfrid Laurier University The Geoscience and Man series is published and distributed by Geoscience Publications, Department of Geography & Anthropology, Louisiana State University. -

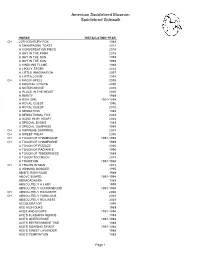

Saddlebred Sidewalk List 1989-2018

American Saddlebred Museum Saddlebred Sidewalk HORSE INSTALLATION YEAR CH 20TH CENTURY FOX 1989 A CHAMPAGNE TOAST 2011 A CONVERSATION PIECE 2014 A DAY IN THE PARK 2018 A DAY IN THE SUN 1999 A DAY IN THE SUN 1998 A KINDLING FLAME 1989 A LIKELY STORY 2014 A LITTLE IMAGINATION 2007 A LOTTA LOVIN' 1998 CH A MAGIC SPELL 2005 A MAGICAL CHOICE 2000 A NOTCH ABOVE 2016 A PLACE IN THE HEART 2000 A RARITY 1989 A RICH GIRL 1991-1994 A ROYAL QUEST 1996 A ROYAL QUEST 2010 A SENSATION 1989 A SENSATIONAL FOX 2002 A SONG IN MY HEART 2004 A SPECIAL EVENT 1989 A SPECIAL SURPRISE 1998 CH A SUPREME SURPRISE 2001 CH A SWEET TREAT 2000 CH A TOUCH OF CHAMPAGNE 1991-1994 CH A TOUCH OF CHAMPAGNE 1989 A TOUCH OF PIZZAZZ 2006 A TOUCH OF RADIANCE 1995 A TOUCH OF TENDERNESS 1989 A TOUCH TOO MUCH 2018 A TRADITION 1991-1994 CH A TRAVELIN' MAN 2012 A WINNING WONDER 1995 ABIE'S IRISH ROSE 1989 ABOVE BOARD 1991-1994 ABRACADABRA 1989 ABSOLUTELY A LADY 1999 ABSOLUTELY COURAGEOUS 1991-1994 CH ABSOLUTELY EXQUISITE 2005 CH ABSOLUTELY FABULOUS 2001 ABSOLUTELY NO LIMITS 2001 ACCELERATOR 1998 ACE HIGH DUKE 1989 ACES AND EIGHTS 1991-1994 ACE'S FLASHING GENIUS 1989 ACE'S QUEEN ROSE 1991-1994 ACE'S REFRESHMENT TIME 1989 ACE'S SOARING SPIRIIT 1991-1994 ACE'S SWEET LAVENDER 1989 ACE'S TEMPTATION 1989 Page 1 American Saddlebred Museum Saddlebred Sidewalk HORSE INSTALLATION YEAR ACTIVE SERVICE 1996 ADF STRICTLY CLASS 1989 ADMIRAL FOX 1996 ADMIRAL'S AVENGER 1991-1994 ADMIRAL'S BLACK FEATHER 1991-1994 ADMIRAL'S COMMAND 1989 CH ADMIRAL'S FLEET 1998 CH ADMIRAL'S MARK 1989 CH ADMIRAL'S MARK -

JOLT Template

NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF LAW & TECHNOLOGY VOLUME 10, ISSUE 1: FALL 2008 PRESERVING COMPETITION IN MULTI-SIDED INNOVATIVE MARKETS: HOW DO YOU SOLVE A PROBLEM LIKE GOOGLE? Kristine Laudadio Devine 1 The unique characteristics of the search advertising industry encourage the development of anticompetitive monopoly power, facilitating the rise and dominance of companies like Google. First, the search advertising industry is subject to multi-sided network effects that create a positive feedback loop. An increase in the number of customers on one side of the market attracts increased numbers of customers on the other side, enabling dominant firms to entrench their market power. Second, and relatedly, the search advertising industry operates in an innovative market where firms compete not to outdo competitors on price but rather to displace one another’s products entirely. In such a market, a dominant firm can acquire potentially displacing (but not substitutive) technology and thereby control future innovation, freeing itself from the burden of innovating further to maintain competitive advantage. Current regulatory enforcement, informed by traditional antitrust analysis, does not adequately account for the impact of multi-sided network effects or innovation-to-displace on competition. Retooling the regulatory regime governing merger enforcement, allowing the agencies tasked with enforcement to broaden their inquiries when investigating anticompetitive behavior of these firms, is therefore necessary to preserve competition in multi-sided innovative markets. I. INTRODUCTION On April 13, 2007, Google, the leading provider of online text- based advertising services, announced its intention to acquire DoubleClick, the leading provider of online display advertising 1 Latham & Watkins, LLP. Juris Doctor, Northwestern University School of Law, 2008. -

Platform Competition in an Age of Machine Learning

DISRUPTIVE INCUMBENTS: PLATFORM COMPETITION IN AN AGE OF MACHINE LEARNING C. Scott Hemphill * Recent advances in machine learning have reinforced the competi- tive position of leading online platforms. This Essay identifies two im- portant sources of platform rivalry and proposes ways to maximize their competitive potential under existing antitrust law. A nascent competitor is a threatening new entrant that, in time, might become a full-fledged platform rival. A platform’s acquisition of a nascent competitor should be prohibited as an unlawful acquisition or maintenance of monopoly. A disruptive incumbent is an established firm—often another plat- form—that introduces fresh competition in an adjacent market. Anti- trust enforcers should take a more cautious approach, on the margin, when evaluating actions taken by a disruptive incumbent to compete with an entrenched platform. INTRODUCTION The leading online platforms—Google in search, Facebook in social network services, and Amazon in e-commerce—benefit from economies of scale and access to user data that are difficult for rivals to replicate. These barriers are reinforced by advances in machine learning, a set of artificial intelligence (AI) techniques1 that use models to “learn” desired behavior from “examples rather than instructions.”2 This Essay considers how competition might be enhanced, notwithstanding these advantages, under existing antitrust law.3 * Moses H. Grossman Professor of Law, New York University School of Law. I thank John Asker, Adam Cox, Harry First, Jacob Gersen, Jeannie Gersen, Bert Huang, Avery Katz, Benedict Kingsbury, Bhaven Sampat, Tim Wu, and audiences at Columbia, ETH Zurich, and NYU, for helpful comments. Tim Keegan, Ryan Knox, Ina Kosova, Alison Perry, and David Stein provided outstanding research assistance. -

Julius Caesar Act I

04_9781118486788-ch01.qxd:9781118486788-ch01.qxd 8/8/12 5:53 PM Page 25 COLES NOTES TOTAL STUDY EDITION JULIUS CAESAR ACT I Scene 1 . 27 Scene 2 . 31 Scene 3 . 46 Cassius Fellow, come from the throng; look upon Caesar. Caesar What say ’st thou to me now? Speak once again. Soothsayer Beware the ides of March. Caesar He is a dreamer. Let us leave him. Pass. COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL 04_9781118486788-ch01.qxd:9781118486788-ch01.qxd 8/8/12 5:53 PM Page 26 04_9781118486788-ch01.qxd:9781118486788-ch01.qxd 8/8/12 5:53 PM Page 27 Coles Notes Total Study Edition Julius Caesar • Act I, Scene 1 27 Act I, A rowdy group of plebians or commoners have gathered in the streets of Scene 1 Rome to celebrate both the Feast of the Lupercal and Julius Caesar’s triumphant return to Rome after defeating the last of his enemies, the sons of Pompey. Two tribunes, Marullus and Flavius, chastise the crowd for adoring Caesar and for celebrating as if it were a holiday. The crowd guiltily disperses and Marullus and Flavius depart to vandalize Caesar’s statues. ACT I, SCENE 1. NOTES Rome, a street. [Enter FLAVIUS, MARULLUS, and certain commoners over the stage.] S.D. over the stage: the commoners cross the stage before halting. In most productions, they enter first, Flavius Hence! home, you idle creatures, get you with Flavius and Marullus following them. home! Is this a holiday? What, know you not, Being mechanical, you ought not to walk 3. Being mechanical: being artisans or workers. -

Emp, An& Juapoleon

gmertca, , ?|emp, an& JUapoleon American Trade with Russia and the Baltic, 1783-1812 BY ALFRED W. CROSBY, JR. Ohio Sttite University Press $6.50 America, IXuaata, S>emp, anb Napoleon American Trade with Russia and the Baltic, 1783-1812 BY ALFRED W. CROSBY, JR. On the twelfth of June, 1783, a ship of 500 tons sailed into the Russian harbor of Riga and dropped anchor. As the tide pivoted her around her mooring, the Russians on the waterfront could see clearly the banner that she flew — a strange device of white stars on a blue ground and horizontal red and white stripes. Russo-American trade had irrevocably begun. Merchants — Muscovite and Yankee — had met and politely sounded the depths of each other's purses. And they had agreed to do business. In the years that followed, until 1812, the young American nation became economically tied to Russia to a degree that has not, perhaps, been realized to date. The United States desperately needed Russian hemp and linen; the American sailor of the early nineteenth century — who was possibly the most important individual in the American economy — thought twice before he took any craft not equipped with Russian rigging, cables, and sails beyond the harbor mouth. To an appreciable extent, the Amer ican economy survived and prospered because it had access to the unending labor and rough skill of the Russian peasant. The United States found, when it emerged as a free (Continued on back flap) America, Hossia, fiemp, and Bapolcon American Trade with Russia and the Baltic, 1783-1812 America, llussia, iicmp, and Bapolton American Trade with Russia and the Baltic, 1783-1811 BY ALFRED W.