William C. C. Claiborne: Profile of a Democrat Author(S): John D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of the Welles Family in England

HISTORY OFHE T WELLES F AMILY IN E NGLAND; WITH T HEIR DERIVATION IN THIS COUNTRY FROM GOVERNOR THOMAS WELLES, OF CONNECTICUT. By A LBERT WELLES, PRESIDENT O P THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OP HERALDRY AND GENBALOGICAL REGISTRY OP NEW YORK. (ASSISTED B Y H. H. CLEMENTS, ESQ.) BJHttl)n a account of tljt Wu\\t% JFamtlg fn fHassssacIjusrtta, By H ENRY WINTHROP SARGENT, OP B OSTON. BOSTON: P RESS OF JOHN WILSON AND SON. 1874. II )2 < 7-'/ < INTRODUCTION. ^/^Sn i Chronology, so in Genealogy there are certain landmarks. Thus,n i France, to trace back to Charlemagne is the desideratum ; in England, to the Norman Con quest; and in the New England States, to the Puri tans, or first settlement of the country. The origin of but few nations or individuals can be precisely traced or ascertained. " The lapse of ages is inces santly thickening the veil which is spread over remote objects and events. The light becomes fainter as we proceed, the objects more obscure and uncertain, until Time at length spreads her sable mantle over them, and we behold them no more." Its i stated, among the librarians and officers of historical institutions in the Eastern States, that not two per cent of the inquirers succeed in establishing the connection between their ancestors here and the family abroad. Most of the emigrants 2 I NTROD UCTION. fled f rom religious persecution, and, instead of pro mulgating their derivation or history, rather sup pressed all knowledge of it, so that their descendants had no direct traditions. On this account it be comes almost necessary to give the descendants separately of each of the original emigrants to this country, with a general account of the family abroad, as far as it can be learned from history, without trusting too much to tradition, which however is often the only source of information on these matters. -

Historical Narrative

Historical Narrative: “Historically, there were two, possibly three, Natchez Traces, each one having a different origin and purpose...” – Dawson Phelps, author of the Natchez Trace: Indian Trail to Parkway. Trail: A trail is a marked or beaten path, as through woods or wildness; an overland route. The Natchez Trace has had many names throughout its history: Chickasaw Trace, Choctaw-Chickasaw Trail, Path to the Choctaw Nation, Natchez Road, Nashville Road, and the most well known, the Natchez Trace. No matter what its name, it was developed out of the deep forests of Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee, from animal paths and well-worn American Indian footpaths. With American ownership of the Mississippi Territory, an overland route linking the area to the growing country was desperately needed for communication, trade, prosperity and defense from the Spanish and English, who were neighbors on the southwestern frontier. While river travel was desirable, a direct land route to civilization was needed from Natchez in order to bring in military troops to guard the frontier, to take things downriver that were too precious to place on a boat, to return soldiers or boatmen back to the interior of the U.S., and for mail delivery and communication. The improvement of the Natchez Trace began over the issue of mail delivery. In 1798, Governor Winthrop Sargent of the Mississippi Territory asked that “blockhouses” be created along American Indian trails to serve was stops for mail carriers and travelers since it took so long to deliver the mail or travel to Natchez. In fact, a letter from Washington D.C. -

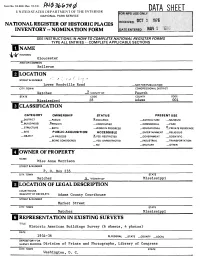

Data Sheet National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DATA SHEET NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ___________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ NAME HISTORIC Gloucester AND/OR COMMON Bellevue LOCATION f' STREET & NUMBER Lower Woodville Road —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Natchez VICINITY OF Fourth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Mississitmi 28 Adams 001 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT _PUBLIC 2LOCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM ?_BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL PARK STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL ^.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS 2LYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY . —OTHER: Miss Anne Morrison STREET & NUMBER P. 0. Box 235 CITY. TOWN STATE Natchez _X_ VICINITY OF Mississippi LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Adams County Courthouse STREETS. NUMBER Market Street CITY. TOWN STATE Natchez Mississippi [1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey (6 sheets, 4 photos) DATE 1934-36 X.FEDERAL _STATE _COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Division of Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress CITY. TOWN STATE Washington, D. C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED X-UNALTERED .X-ORIGINALSITE —RUINS _ALTERED —MOVED DATE- —FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Gloucester is a large, two-story brick mansion located east of the Lower Woodville Road near Natchez, Mississippi. It is one of several prominent Neo-Classical "suburban villas" in the Natchez region, but is unique because its final form was reached through an artful renovation and enlargement program. -

2014 Historical-Statistical Info.Indd

SOS6889 Divider Pages.indd 15 12/10/12 11:32 AM HISTORICAL AND STATISTICAL INFORMATION HISTORICAL AND STATISTICAL INFORMATION Mississippi History Timeline . 743 Historical Roster of Statewide Elected Officials . 750 Historical Roster of Legislative Officers . 753 Mississippi Legislative Session Dates . 755. Mississippi Historical Populations . 757 Mississippi State Holidays . 758 Mississippi Climate Information . 760 2010 U.S. Census – Mississippi Statistics . 761 Mississippi Firsts . 774 742 HISTORICAL AND STATISTICAL INFORMATION MISSISSIPPI HISTORY TIMELINE 1541: Hernando De Soto, Spanish explorer, discovers the Mississippi River. 1673: Father Jacques Marquette, a French missionary, and fur trapper Louis Joliet begin exploration of the Mississippi River on May 17. 1699: First European settlement in Mississippi is established at Fort Maurepas, in present-day Ocean Springs, by Frenchmen Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville and his brother, Jean Baptiste de Bienville. 1716: Bienville establishes Fort Rosalie on the site of present-day Natchez. 1718: Enslaved Africans are brought to Mississippi by the Company of the West. 1719: Capital of the Louisiana colony moves from Mobile to New Biloxi, present-day Biloxi. 1729: The Natchez massacre French settlers at Fort Rosalie in an effort to drive out Europeans. Hundreds of slaves were set free. 1754: French and Indian War begins. 1763: Treaty of Paris ends the French and Indian War with France giving up land east of the Mississippi, except for New Orleans, to England. 1775: The American Revolution begins with many loyalists fleeing to British West Florida, which included the southern half of present-day Mississippi. 1779- 1797: Period of Spanish Dominion with Manuel Gayosa de Lemos chosen governor of the Natchez region. -

Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations from the Revolution Through the Civil War General Editor: Kenneth M

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Records of Ante-Bellum Southern Plantations from the Revolution through the Civil War General Editor: Kenneth M. Stampp Series J Selections from the Southern Historical Collection, Manuscripts Department, Library of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Part 6: Mississippi and Arkansas Associate Editor and Guide Compiled by Martin Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Records of ante-bellum southern plantations from the Revolution through the Civil War [microform] Accompanied by printed reel guides, compiled by Martin Schipper. Contents: ser. A. Selections from the South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina (2 pts.) -- [etc.] --ser. E. Selection from the University of Virginia Library (2 pts.) -- -- ser. J. Selections from the Southern Historical Collection Manuscripts Department, Library of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (pt. 6). 1. Southern States--History--1775–1865--Sources. 2. Slave records--Southern States. 3. Plantation owners--Southern States--Archives. 4. Southern States-- Genealogy. 5. Plantation life--Southern States-- History--19th century--Sources. I. Stampp, Kenneth M. (Kenneth Milton) II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Schipper, Martin Paul. IV. South Caroliniana Library. V. South Carolina Historical Society. VI. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. VII. Maryland Historical Society. [F213] 975 86-892341 ISBN -

Entire Issue Volume 9, Number 4

The Primary Source Volume 9 | Issue 4 Article 1 1987 Entire Issue Volume 9, Number 4 Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/theprimarysource Part of the Archival Science Commons Recommended Citation (1987) "Entire Issue Volume 9, Number 4," The Primary Source: Vol. 9 : Iss. 4 , Article 1. DOI: 10.18785/ps.0904.01 Available at: https://aquila.usm.edu/theprimarysource/vol9/iss4/1 This Complete Issue is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in The rP imary Source by an authorized editor of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Quarterly Publication of The Society of Mississippi Archivists Volume 9 Winter 1988 Number 4 NEWSPAPER PROJEti' AWARDED MICROFIIJfiNG GRANT The Mississippi Ne,..Tspaper Project has received a grant of $26,317 from the National Endowment for the Humanities to microfilm selected Mississippi ne,..Tspapers that are in danger of being lost because of negligence, deterioration or destruction. The microfilming will be undertaken in conjunction with the bibliosraphic phase of the Newspaper Project. A proposal for a two-year microfilming phase of the project has been sent to NEH. The current grant covers an eight-month period, through August 1988. Glenda Stevens will oversee the daily operation of the microfilming project, assisted by Joe Brent, newspaper archivist, and Michael ·Johnson, microfilm camera operator. Dale Foster is coordinator of the newspaper project. WORKSHOPS SET FOR SAC MEETING Plans for the joint SMA/SALA spring meeting, the first formal meeting of the Southeastern Archivists' Conference (SAC) are progressing. -

Entire Issue Volume 10, Number 1

The Primary Source Volume 10 | Issue 1 Article 1 1988 Entire Issue Volume 10, Number 1 Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/theprimarysource Part of the Archival Science Commons Recommended Citation (1988) "Entire Issue Volume 10, Number 1," The Primary Source: Vol. 10 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. DOI: 10.18785/ps.1001.01 Available at: https://aquila.usm.edu/theprimarysource/vol10/iss1/1 This Complete Issue is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in The rP imary Source by an authorized editor of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Quarterly Publication of The Society of Mississippi Archivists Volume 10 Spring 1988 Number 1 [ --------- SAC TO MEET AT OLE KISS The Southern Archivists' Conference announces its first meeting, to be held at the University of Mississippi, Oxford, May 17-19, 1988. Created in April 1987 by the state archival societies of Alabama and Mississippi, SAC is still very much in its formative period, and this first meeting is an experiment to see what the best regional approach to Southern archives will be. The meeting is open to all interested archivists and other records custodians and will provide the opportunity for continuing education through three workshop offerings, regional gatherings of national interest groups, and discussions of current professional issues. At the conclusion, there Hill be a general discussion of future directions that. SAC should take. The meetine will be in Oxford, Mississippi, home of William Faulkner and the Blues Archive, and participants will have a chance to sample both. -

Northwest Ohio Quarterly Volume 18 Issue 3

Northwest Ohio Quarterly Volume 18 Issue 3 Northwest Ohio Quarterly t EDITORIAL BOARD MILO M. QUAIFE ANDREW J. TOWNSEND SPENCER A. CANARY FRED LANDON FRANCIS P. WEISENBURGER CURTIS W. GARRISON ANDREW J. TOWNSEND, Managing Editor G. HARRISON ORIANS, Review Editor JESSER. LoNG, News Editor t July, 1946 VOLUME 18 NUMBER 3 ,,, 41 l! t ,. ' Published by l ', , THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF NORTHWESTERN OHIO ' TOLEDO Contents In This Issue .. .. ............ .... ..... ...... 99 The article on 1 ~ of Toledo and to ; The President's Page: Due Process of Law .. ... 100 western Ohio> has News: Forest Established for World War II Shrine ... 102 pastor of Collingw has been intimatelJ Fort Meigs Park Addition Dedicated ........ 102 as his pastor. Historical Displays at Toledo Public Library ... 103 Mrs. Mildred M of the Local H isto1 History Honorary Initiates Five ............ 103 has written an int Toledo Organizations Honor Retiring Professor 104 ment. This will bt not only because t History Staff Enlarged at Bowling Green . .... 105 ciety> but because 1 Other Personal Notes .. ..... .... .. .... 105 history. Dr. Benjamin E Judge Silas E. Hurin, by R. Lincoln Long .. .. .. 106 of Students at Wit1 Local History and Genealogy in the Toledo Public Li- on "Winthrop Sa; brary, by Mildred M. Shepherst ...... .. ...... 108 troit" presents an activities while Sec Winthrop Sargent and the American Occupation of Territory which is Detroit, by Benjamin H. Pershing .. ......... 114 ber of recent writt Books ....... .. .. .. ......... ... ........ .. .. 126 students. 98 -In This Issue ANDREW J. TOWNSEND . 99 The article on Judge Silas E. Hurin, well known to residents of Toledo and to members of the Historical Society of North f Law . -

The Ohio Company and the Meaning of Opportunity in the American West 1786-1795

History Faculty Publications History 9-1991 The Ohio ompC any and the Meaning of Opportunity in the American West 1786-1795 Timothy J. Shannon Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/histfac Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Shannon, Timothy J. "The Ohio ompC any and the Meaning of Opportunity in the American West, 1786-1795," New England Quarterly, 64 (September 1991): 393-413. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/366349. This is the publisher's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/histfac/7 This open access article is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Ohio ompC any and the Meaning of Opportunity in the American West 1786-1795 Abstract Founded in 1786 by former officers of the Continental Army to promote an orderly expansion of American society westward, the Ohio Company soon succumbed to the desire of many of its investors to make money. The aims of settlement warred with the desire to make a profit through land speculation; eventually the company dissolved, a casualty of its inability to reconcile the varied interests of shareholders and to manage westward development. Keywords Ohio Company, Officers' Petition, Western Expansion, Post-Revolutionary America, Emigration, Articles of Association Disciplines Cultural History | History | United States History This article is available at The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/histfac/7 The Ohio Company and the Meaning of Opportunity in the AmericanWest, 1786-1795 TIMOTHY J. -

Harlow Lindley Collection, 1790-1914

Indiana Historical Society - Manuscripts and Archives Department HARLOW LINDLEY COLLECTION, 1790-1914 Collection #'s M 0186 OM 0302 Table of contents Collection Information Biographical Sketches Scope and Content Note Box and Folder List Cataloging Information Processed by Charles Latham, jr.1985 Reprocessed Alexandra S. Gressitt February 1998 COLLECTION INFORMATION VOLUME OF 1-1/2 manuscript boxes, 2 oversize folders COLLECTION: COLLECTION DATES: 1790-1926 PROVENANCE: Acquired from Ernest Wessen, Midland Rare Book Company, Mansfield, Ohio, 1948 RESTRICTIONS: None REPRODUCTION Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection RIGHTS: must be obtained in writing from the Indiana Historical Society. ALTERNATE FORMATS: None OTHER FINDING AIDS: None RELATED HOLDINGS: ACCESSION NUMBER: 1948.0003 NOTES: BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES Harlow Lindley (1875-1959), a native of Sylvania, Parke County, Indiana, did undergraduate and graduate work at Earlham College, and taught in the history department, 1899 to 1928. From 1903 to 1924 he also served as part-time director of the Department of History and Archeology at the Indiana State Library, and in 1923-1924 he was director of the Indiana Historical Commission. In 1929 he moved to Ohio, to become curator of history of the Ohio State Archeological and Historical Society in Columbus. In 1934, he became Secretary of the Society, a position he held until his retirement in 1946. Among his works are A Century of Quakerism in Indiana, The Ordinance of 1787 and the Old Northwest Territory, and Indiana As Seen By Early Travellers. Charles Warren Fairbanks (1852-1918) was born near Unionville, Ohio, and attended Ohio Wesleyan University. Admitted to the bar in 1874, he moved to Indianapolis and began a legal career representing railroads. -

Former Officials of Michigan French-Canadian Governors, 1603-1760

FORMER OFFICIALS OF MICHIGAN FRENCH-CANADIAN GOVERNORS, 1603-1760 No. Name Title Year 1 Aymar de Chastes, Sieur de Monts....................... 1603-12 2 Samuel de Champlain with Prince de Conde as acting governor.. 1612-19 3 Henry, Duke of Montmorenci, acting governor ............. 1619-29 4 Samuel de Champlain1 ............................... Lieut. Gen. and Viceroy.. 1633 { 1635 5 Marc Antoine de Bras-de-Fer de Chateaufort ............... Lieut. Gen. and Viceroy.. 1636 6 Charles Hualt de Montmagny .......................... Gov. and Lieut. Gen. ... 1636-47 7 Louis d’Ailleboust, Sieur de Coulonges ................... Governor ............ 1648-51 8 Jean de Lauson..................................... Governor ............ 1651-55 9 Charles de Lauson-Charny2 ............................ Governor ............ 1656-57 10 Louis d’Ailleboust, Sieur de Coulonges3 ................... Governor ............ 1657-58 11 Pierre de Voyer, Viscount d’Argenson .................... Governor ............ 1658-61 12 Baron Dubois d’Avaugour............................. Governor ............ 1661-63 13 Augustin de Saffray-Mezy ............................. Governor ............ 1663-65 14 Alexandre de Prouville, Marquis de Tracy ................. Viceroy ............. 1663 15 Daniel Remy, Sieur de Courcelles ....................... Gov. and Lieut. Gen. ... 1665-72 16 Louis de Buade, Count de Frontenac..................... Governor ............ 1672-82 17 Antoine Joseph Le Febvre de la Barre .................... Governor ............ 1682-85 18 Jacques Rene -

Tonnancour Redo.Indd

A County Is Proclaimed: The Founding of Wayne County and Grosse Pointe Township by Clarence M. Burton On August 15, 1796, only a month after the arrival of the first American troops in Detroit, Winthrop Sargent, secretary and acting governor of the Northwest Territory, issued a proclamation formally establishing Wayne County. Named in honor of General Anthony Wayne, the county included most of Michigan, and parts of present-day Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. Two years later, on November 1, 1798, the county was divided into four townships, one of which was named Hamtramck. On April 1, 1848 Hamtramck Township was divided, and the Township of Grosse Pointe was formed. Wayne County was consequently ignored. Wayne County was established August 15, 1796, by the fol- HE FIRST MOVE to establish a county west lowing proclamation issued by Winthrop Sargent, secretary of the Allegheny Mountains was made by the and acting governor of the Northwest Territory: Virginia Legislature in October, 1778, when “To all persons to whom these presents shall come — Greeting: an act was passed creating Illinois County, “Whereas, by an ordinance of Congress of the thirteenth of which included all the region afterward July, one thousand seven hundred and eighty-seven, for the set- Tembraced in the Northwest Territory. On June 16, 1792, tlement of the Territory of the United States Northwest of the four years before Detroit became an American possession, River Ohio, it is directed that for the due execution of process, John Graves Simcoe, lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada, civil and criminal, the Governors shall make proper Divisions issued a proclamation establishing Kent County, which of the said Territory and proceed from time to time, as circum- embraced all of the present State of Michigan and extended stances may require, to lay out the same into Counties and northward to the Hudson’s Bay country.