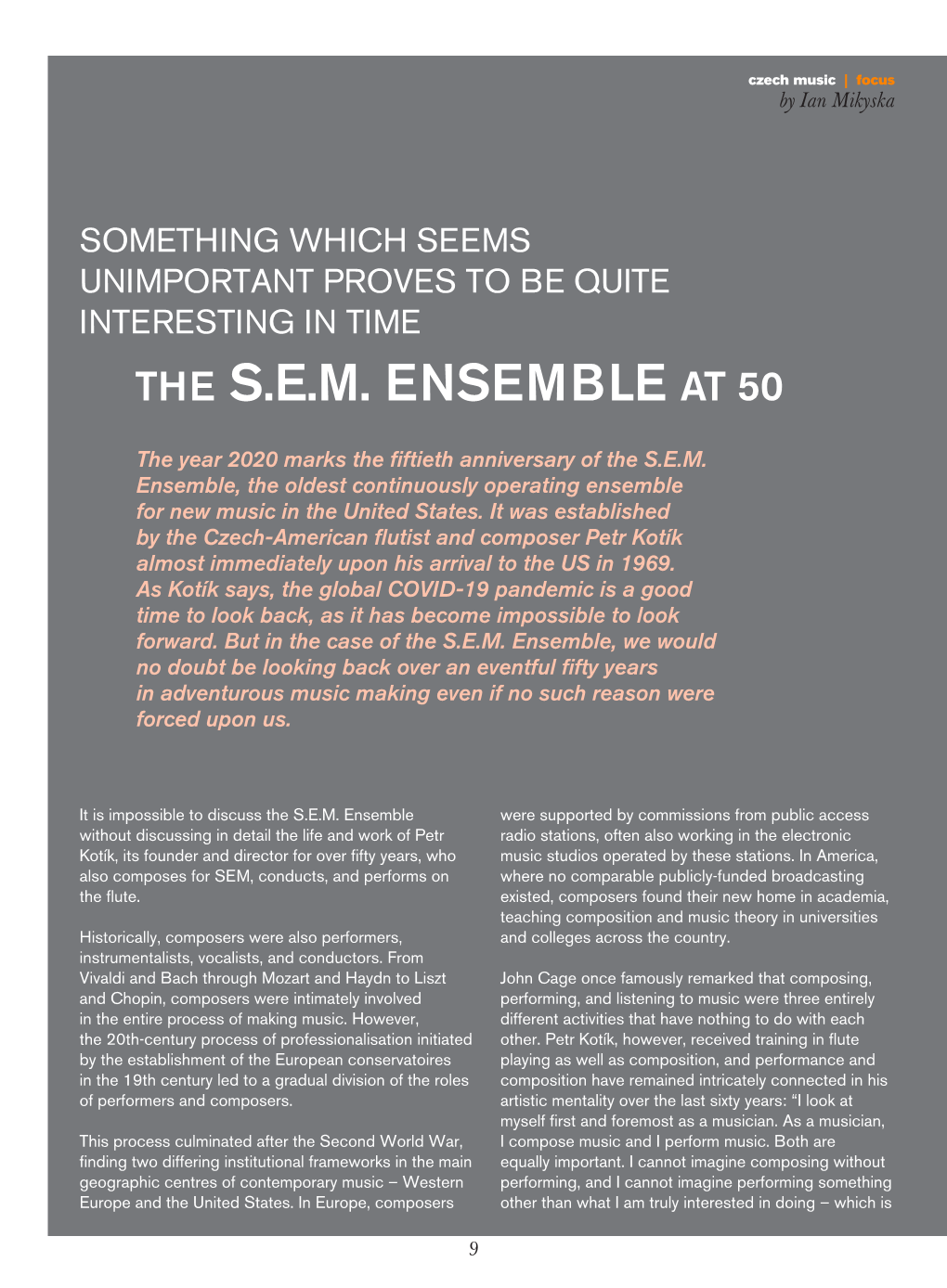

The S.E.M. Ensemble at 50

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liner Notes, Visit Our Web Site: Recording: March 22, 2012, Philharmonie in Berlin, Germany

21802.booklet.16.aas 5/23/18 1:44 PM Page 2 CHRISTIAN WOLFF station Südwestfunk for Donaueschinger Musiktage 1998, and first performed on October 16, 1998 by the SWF Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Jürg Wyttenbach, 2 Orchestra Pieces with Robyn Schulkowsky as solo percussionist. mong the many developments that have transformed the Western Wolff had the idea that the second part could have the character of a sort classical orchestra over the last 100 years or so, two major of percussion concerto for Schulkowsky, a longstanding colleague and friend with tendencies may be identified: whom he had already worked closely, and in whose musicality, breadth of interests, experience, and virtuosity he has found great inspiration. He saw the introduction of 1—the expansion of the orchestra to include a wide range of a solo percussion part as a fitting way of paying tribute to the memory of David instruments and sound sources from outside and beyond the Tudor, whose pre-eminent pianistic skill, inventiveness, and creativity had exercised A19th-century classical tradition, in particular the greatly extended use of pitched such a crucial influence on the development of many of his earlier compositions. and unpitched percussion. The first part of John, David, as Wolff describes it, was composed by 2—the discovery and invention of new groupings and relationships within the combining and juxtaposing a number of “songs,” each of which is made up of a orchestra, through the reordering, realignment, and spatial distribution of its specified number of sounds: originally between 1 and 80 (with reference to traditional instrumental resources. -

"For Philip Guston" by Petr Kotik and Walter Zimmermann

[Morton Feldman Page] [List of Texts] On Performing Feldman's "For Philip Guston": A Conversation by Petr Kotik and Walter Zimmermann Contents: Introduction to Petr Kotik/Walter Zimmermann Conversation by Petr Kotik Ten Nasty Questions put to Petr Kotik by Walter Zimmermann Introduction to Petr Kotik/Walter Zimmermann Conversation Following the performance by S.E.M. Ensemble of Morton Feldman's For Philip Guston at the Paula Cooper Gallery in May, 1995, Paula Cooper suggested that we record the piece. She offered to fund the project the same way she funded our Marcel Duchamp recording in 1989. We had a few meetings in the Fall of 1995, to assess the feasibility of the idea and in November, we decided to go ahead. On December 22 and 23, 1995, we recorded the piece at the LRP Studio on West 22nd Street in Manhattan. The May '95 performance of Guston at the Paula Cooper Gallery was a great success. That Spring, we performed the piece twice: once in New York and few weeks later at the Landesmuseum Mainz in Germany. These were not our first performances of Guston. We have already performed it in 1988. Both concerts in 1995 convinced me that the time has finally come for music of extended duration to be appreciated by broader audiences. I was very much involved with this concept in the 1970s. In fact, all the pieces I wrote between 1971 and 1981 are several hours in duration. In the Summer of 1987, I wanted to commission Feldman to write a piece for the S.E.M. -

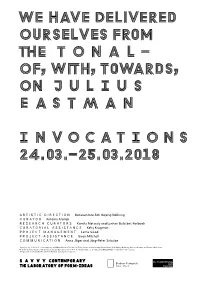

Of, With, Towards, on JULIUS EASTMAN INVOCATIONS 24.03

We Have Delivered Ourselves From the TONAL– Of, with, towards, On J U L I U S EASTMAN I NVOCATIONS 24.03.–25.03.2018 ARTISTIC DIRECTION Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung CURATOR Antonia Alampi RESEARCH CURATORS Kamila Metwaly and Lynhan Balatbat-Helbock CURATORIAL ASSISTANCE Kelly Krugman PROJECT MANAGEMENT Lema Sikod PROJECT ASSISTANCE Gwen Mitchell COMMUNICATION Anna Jäger and Jörg-Peter Schulze A project by S A V V Y Contemporary and MaerzMusik – Festival for Time Issues, conceived by Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, Antonia Alampi and Berno Odo Polzer. New works have been commissioned and produced by S A V V Y Contemporary, co-produced by MaerzMusik – Festival for Time Issues. The project is funded by the German Federal Cultural Foundation. SAVVY Contemporary The Laboratory of Form-Ideas OUTLINE WE HAVE DELIVERED OURSELVES EXHIBITION 24.03.–06.05.2018 FROM THE TONAL is an exhibition, and OPEN Thu–Sun 14:00–19:00 a programme of performances, concerts and lectures WITH Paolo Bottarelli Raven Chacon that deliberate around concepts beyond the predomi- Tanka Fonta Malak Helmy Hassan Khan Annika Kahrs nantly Western musicological format of the tonal Pungwe (Robert Machiri and Memory Biwa) or harmonic. The project looks at African American The Otolith Group (Anjalika Sagar and Kodwo Eshun) composer, musician and performer Julius Eastman’s Christine Rusiniak Barthélémy Toguo work beyond the framework of what is today under- SAVVY Contemporary stood as minimalist music, within a larger, always gross Plantagenstraße 31, 13347 Berlin and ever-growing understanding of it – i.e. conceptually and geo-contextually. Together with musicians, visual INVOCATIONS I 24.03.2018 16:00–24:00 artists, researchers and archivers, we aim to explore INVOCATIONS II 25.03.2018 11:00–20:30 a non-linear genealogy of Eastman’s practice and his silent green Kulturquartier cultural, political and social weight, and situate his work Gerichtstraße 35, 13347 Berlin within a broader rhizomatic relation of musical episte- mologies and practices. -

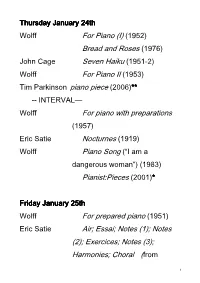

Programme Notes

Thursday January 24th Wolff For Piano (I) (1952) Bread and Roses (1976) John Cage Seven Haiku (1951-2) Wolff For Piano II (1953) Tim Parkinson piano piece (2006)****** -- INTERVAL— Wolff For piano with preparations (1957) Eric Satie Nocturnes (1919) Wolff Piano Song (“I am a dangerous woman”) (1983) Pianist:Pieces (2001) *** Friday January 25th Wolff For prepared piano (1951) Eric Satie Air; Essai; Notes (1); Notes (2); Exercices; Notes (3); Harmonies; Choral (from 1 'Carnet d'esquisses et do croquis', 1900-13 ) Wolff A Piano Piece (2006) *** Charles Ives Three-Page Sonata (1905) Steve Chase Piano Dances (2007-8) ****** Wolff Accompaniments (1972) --INTERVAL— Wolff Eight Days a Week Variation (1990) Cornelius Cardew Father Murphy (1973) Howard Skempton Whispers (2000) Wolff Preludes 1-11 (1980-1) Saturday January 26th Christopher Fox at the edge of time (2007) *** Wolff Studies (1974-6) Michael Parsons Oblique Pieces 8 and 9 (2007) ****** 2 Wolff Hay Una Mujer Desaparecida (1979) --INTERVAL-- Wolff Suite (I) (1954) For pianist (1959) Webern Variations (1936) Wolff Touch (2002) *** (** denotes world premiere; *** denotes UK premiere) for pianist: the piano music of Christian Wolff Given the importance within Christian Wolff’s compositional aesthetic of music which involves interaction between players, it is perhaps surprising that there is a significant body of works for solo instrument. In particular the piano proves to be central 3 to Wolff’s output, from the early 1950s to the present day. These concerts include no fewer than sixteen piano solos; I have chosen not to include a number of other works for indeterminate instrumentation which are well suited to the piano (the Tilbury pieces for example) as well as two recent anthologies of short pieces, A Keyboard Miscellany and Incidental Music , and also Long Piano (Peace March 11) of which I gave the European premiere in 2007. -

Petr Kotík Ve Víru Hudební Avantgardy Šedesátých Let Petr Kotik in the Mindst of Musical Avant-Garde of the Nineteen Sixties

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Filozofická fakulta Katedra muzikologie Petr Kotík ve víru hudební avantgardy šedesátých let Petr Kotik in the Mindst of Musical Avant-garde of the Nineteen Sixties Bakalářská práce Autor práce: Eva Balcárková Vedoucí práce: Doc. PhDr. Lenka Křupková, PhD. Olomouc 2015 Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci na téma Petr Kotík ve víru hudební avantgardy šedesátých let vypracovala samostatně a uvedla jsem všechny použité zdroje a literaturu. V Olomouci dne ………………………………. Podpis …………..……………………. Děkuji především panu Petru Kotíkovi za ochotu a čas, které mi věnoval během našich konzultací. Dále bych ráda vzdala dík všem organizacím a osobám, které mi poskytly cenné materiály a v neposlední řadě děkuji paní Doc. PhDr. Lence Křupkové, PhD., za vedení práce. Obsah Úvod ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 Koncepce práce a dosavadní stav bádání ............................................................................................ 6 Charakteristika kulturního prostředí, ve kterém Petr Kotík vyrůstal ...................................................... 8 Počátky vlastní tvorby ........................................................................................................................... 10 Studia na pražské konzervatoři ......................................................................................................... 10 Spolupráce s Vladimírem Šrámkem a vlivy ze zahraničí -

To the Fullest: Organicism and Becoming in Julius Eastman's Evil

Title Page To the Fullest: Organicism and Becoming in Julius Eastman’s Evil N****r (1979) by Jeffrey Weston BA, Luther College, 2009 MM, Bowling Green State University, 2012 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2020 Committee Page UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jeffrey Weston It was defended on April 8, 2020 and approved by Jim Cassaro, MM, MLS, Department of Music Autumn Womack, PhD, Department of English (Princeton University) Amy Williams, PhD, Department of Music Dissertation Co-Director: Michael Heller, PhD, Department of Music Dissertation Co-Director: Mathew Rosenblum, PhD, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Jeffrey Weston 2020 iii Abstract To the Fullest: Organicism and Becoming in Julius Eastman’s Evil N****r (1979) Jeffrey Weston, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2020 Julius Eastman (1940-1990) shone brightly as a composer and performer in the American avant-garde of the late 1970s- ‘80s. He was highly visible as an incendiary queer black musician in the European-American tradition of classical music. However, at the end of his life and certainly after his death, his legacy became obscured through a myriad of circumstances. The musical language contained within Julius Eastman’s middle-period work from 1976-1981 is intentionally vague and non- prescriptive in ways that parallel his lived experience as an actor of mediated cultural visibility. The visual difficulty of deciphering Eastman’s written scores compounds with the sonic difference in the works as performed to further ambiguity. -

Explorations of Dissent in the Music of Czech-Born Composers Marek Kopelent and Petr Kotík

Notes from the Underground: Explorations of Dissent in the Music of Czech-born Composers Marek Kopelent and Petr Kotík by Victoria Johnson A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Approved November 2015 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Sabine Feisst, Chair Robert Oldani Jody Rockmaker ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY December 2015 ABSTRACT Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, musicologists have been delving into formerly inaccessible archives and publishing new research on Eastern Bloc composers. Much of the English-language scholarship, however, has focused on already well-known composers from Russia or Poland. In contrast, composers from smaller countries such as the Czech Republic (formerly Czechoslovakia) have been neglected. In this thesis, I shed light on the new music scene in Czechoslovakia from 1948–1989, specifically during the period of “Normalization” (1969–1989). The period of Normalization followed a cultural thaw, and beginning in 1969 the Czechoslovak government attempted to restore control. Many Czech and Slovak citizens kept their opinions private to avoid punishment, but some voiced their opinions and faced repression, while others chose to leave the country. In this thesis, I explore how two Czech composers, Marek Kopelent (b. 1932) and Petr Kotík (b. 1942) came to terms with writing music before and during the period of Normalization. My research draws on the work of Cold War scholars such as Jonathan Bolton, who has written about popular music during Normalization, and Thomas Svatos, who has written about the art music scene during the fifties. For information particular to art music during Normalization, I have relied on primary sources including existing interviews with the composers. -

The John Cage Festival

Special Thanks The John Cage The Florida State University College of Music Don Gibson, Dean Leo Welch, Associate Dean Festival Clifton Callender, Associate Professor of Composition Richard Clary, Professor & Director of Advanced Wind Ensembles who have helped to make this event possible. And all of the festival participants and attendees Mary Luisi, Nowell Gatica, and student volunteers Kristen Klehr, Jeff Miller, Matthew Martin, Elizabeth Tilley Anne Garree, Bruce Hargabus, and the FSU Piano Technology program Anthony Morgan and the FSU School of Dance Laura Gayle Green, Sara Nodine, and the Warren D. Allen Music Library Nicholas Smith and the College of Music Recital Hall Staff Kim Shively and the University Musical Associates Wendy Smith and Karey Fowler Richard Clary, Professor & Director of Advanced Wind Ensembles Clifton Callender, Associate Professor of Composition Leo Welch, Associate Dean Don Gibson, Dean The Florida State University College of Music Special Thanks Wendy Smith and Karey Fowler Kim Shively and the University Musical Associates The Florida State University Nicholas Smith and the College of Music Recital Hall Staff College of Music Laura Gayle Green, Sara Nodine, and the Warren D. Allen Music Library Anthony Morgan and the FSU School of Dance October 25 - 27, 2012 Anne Garree, Bruce Hargabus, and the FSU Piano Technology program Kristen Klehr, Jeff Miller, Matthew Martin, Elizabeth Tilley Mary Luisi, Nowell Gatica, and student volunteers And all of the festival participants and attendees Works of who have helped to make this event possible. John Cage/Morton Feldman Christian Wolff/Petr Kotik/James Tenney Antoine Beuger/Manfred Werder Michael Pisaro/Nomi Epstein/Mark So Jennie Gottschalk/Anthony Morgan With a long-standing reputation as one of the premiere music institutions in the nation, the College of Music is a vital component of The Florida State University community, off ering a comprehensive program of instruction and serving as a center of excellence for the cultural development of the state. -

The Music of Julius Eastman

“Damned Outrageous”: The Music of Julius Eastman In January of 1991 I published, in The Village Voice, an obituary for a composer who had died at age 49 the previous May. Active as he had been on the music scene of the 1980s, none of his closest associates on that scene knew he had already been dead for eight months. And when I called around for comments, some were skeptical of my news—because rumors of his death had circulated before. Such was the peculiar life of Julius Eastman, and its tragic, mysterious, yet somehow logical end. Julius Eastman (1940–1990) was a taut, wiry, gay African-American man. He had such an appearance of athleticism and pent-up energy that he could look dangerous, yet he had a gentle sense of humor, and his deep sepulchral voice, incommensurate with his slight figure, conveyed the solemn authority of a prophet. He was a fiery pianist, and a singer of phenomenal range and power. In 1970 he gave the American premiere, at Aspen, of Peter Maxwell Davies’s Eight Songs for a Mad King, a crazy theater piece depicting the descent into dementia of King George III, and one of the most difficult and demanding vocal works of the avant-garde. His astounding 1973 recording of the piece for Nonesuch was probably the closest he ever came to any visibility in the mainstream music world—until now. Born October 27, 1940, Eastman began studying piano at the age of fourteen, showing quick promise, and became a paid chorister in the Episcopal church in Ithaca, New York, where he was raised. -

0Stravská Banda 0N T0ur

Pages 12,01 CD 01 01. LuCa FranCesConi. riti neuraLi (1991) 15:01 ostravská banDa. Hana kotková (vioLin). (pubL. by G. riCorDi & Co.) ostravská banDa. Hana kotková (vioLin). st. WenCesLas CHurch, ostrava. Czech raDio Live reCorDinG, Oct. 25, 2010. 2. petr bakLa. serenaDe (2010) 8:54 Ostravská ostravská banDa. st. WenCesLas CHurch, ostrava. Czech raDio Live reCorDinG, Oct. 25, 2010. 3. pauLina załubska. Dispersion (2007) 6:13 banda On tOur ostravská banDa. La Fabrika, praGue. ContempuLs FestivaL Live reCorDinG, nov. 5, 2010. 4. somei satoH. The passion (2009) 30:23 ostravská banDa. CantiCum ostrava. Thomas buCkner (baritone). GreGory purnHaGen (baritone). Czech raDio ostrava stuDio reCorDinG, Oct. 24, 2010. Lubomír výrek (sounD enGineer). František mixa (proDuCer). CD 2 1. JoHn CaGe. ConCert For piano anD orchestra (1957-58) 22:31 (pubLisHeD by C. F. peters Corp./Henmar press) ostravská banDa. JosepH kubera (piano). La Fabrika, praHa ContempuLs FestivaL Live reCorDinG, nov. 5, 2010. 2. petr kotík. in Four parts (3,6 & 11 For JoHn CaGe) (2009) 24:02 ostravská banDa. La Fabrika, praGue. ContempuLs FestivaL Live reCorDinG, nov. 5, 2010. Works by John Cage. Petr kotík. somei satoh. 3. bernHarD LanG. monaDoLoGie IV (2008) 12:29 (pubLisHeD by zeitvertrieb Wien berLin, 1010 vienna, austria) bernhard Lang. LuCa FranCesConi. Petr bakLa. PauLina ZaLubsk a. ostravská banDa. La Fabrika, praGue. ContempuLs FestivaL Live reCorDinG, nov. 5, 2010. ostravská banda: hana kotková (vioLin). thomas buCkner (baritone). JosePh kubera (Piano). gregory Purnhagen (baritone). Petr kotík (ConduCtor). mutablemusic 109 W 27th st 8th floor, NeW York, NY 10001, PhoNe: 212.627.0990 fax: 212.627.5504, email: [email protected], mutablemusic.com ©2011, ©2011 mutable music. -

Call It Spectral | Village Voice

Call It Spectral BY KYLE GANN TUESDAY, APRIL 27, 2004 AT 4 A.M. 1 American expat pianist Heather O'Donnell BERLIN—For the first time, it feels like the reign of postserialist music is over in Europe. Not that there isn't a lot of postserialist music I love. But Boulez's , Stockhausen's , and Nono's have come to feel like Brahmsian classics of my youth now, and Europe's reluctance to keep evolving musically has seemed scarily perverse. My first night at the MaerzMusik festival, March 19, in Berlin (where I was invited to tangentially talk on a panel about American music), made me fear more of the same. A brand-new work by French composer George Aperghis, , however brilliantly performed, regurgitated Boulezian vocal and mallet-percussion riffs that feel threadbare with use by this point. And so the next evening, even if less impressive in a way, allowed me to exhale with relief, and made it seem that Europe was exhaling as well. by Georg Friedrich Haas, played by the SWR Symphony Orchestra of Baden-Baden and Freiburg under the baton of Sylvain Cambreling, was admittedly not as elegantly written as , but at least it ventured boldly out of serialist territory. Big atonal sonorities moved in chaotic parallel, and for once a recent out of serialist territory. Big atonal sonorities moved in chaotic parallel, and for once a recent European had put away his tiny tools and microscope, and was painting with a big brush. Several minutes in, a pulsing single note from a marimba began to infect the entire orchestra. -

BEYOND CAGE Festival "John Cage at 100 / Music at 2012" New York City, October 22 – November 7

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Isabelle Deconinck La PR - Press & Marketing for the Arts 646-623-1709 S.E.M. Ensemble presents BEYOND CAGE Festival "John Cage at 100 / Music at 2012" New York City, October 22 – November 7 HIGHLIGHTS: * Major large-scale works by John Cage, including Atlas Eclipticalis and Winter Music heard together in their entirety for the first time, and the N.Y. premiere of his last orchestra work, 103 (for a 103-piece orchestra); solos Freeman Etudes and Music of Changes * American premieres of Morton Feldman's Violin and Orchestra and Flute and Orchestra * World Premiere of Christian Wolff's individuals, collective, his first major symphony orchestra work presented in North America * World premieres by Roscoe Mitchell, Alex Mincek, and Kate Soper, among others * First U.S. staged production of Salvatore Sciarrino's” one-act ecstasy” chamber opera Infinito nero * Works by Earle Brown, Petr Kotik, Christian Marclay, Luigi Nono, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and James Tenney Stern Auditorium / Perelman Stage at Carnegie Hall; Alice Tully Hall, Lincoln Center; The Graduate Center, CUNY; Roulette; ISSUE Project Room; Paula Cooper Gallery; Bohemian National Hall; Willow Place Auditorium “It is the polemical work that becomes the spokesman for any age – like the music of John Cage.”—Morton Feldman NEW YORK, NY, August 13, 2012—In conjunction with the centennial of John Cage’s birth, artistic director Petr Kotik and S.E.M. Ensemble, Inc present “BEYOND CAGE – John Cage at 100 / Music at 2012”, a festival highlighting some of Cage’s most significant works and his legacy in the music of our time.