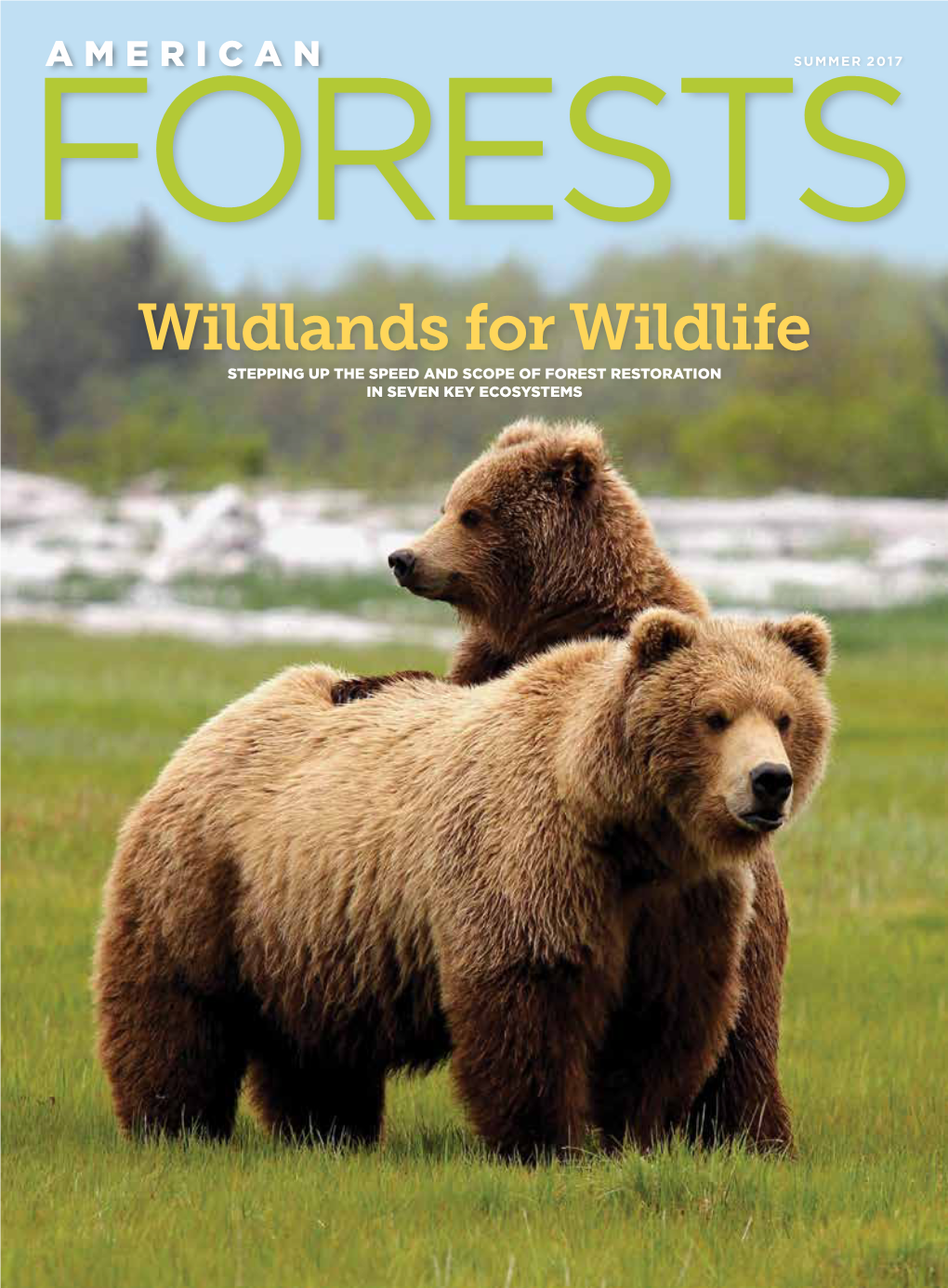

Wildlands for Wildlife

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colchester Natural History Society

COLCHESTER NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY COLCHESTER BOROUGH COUNCIL (CBC) LOCAL PLAN EXAMINATION MAIN MATTER 6 SOUTH COLCHESTER POLICY SC2 MIDDLWICK RANGES 1. In August 2017 Colchester Natural History Society (CNHS) responded to the CBC Draft Local Plan by acknowledging the policy plan to review the Middlewick ecology. In August 2019 in response to a ‘masterplan consultation’ CNHS opposed development citing species rarity and closeness to SSSI sites and added that as the Local Plan at that time had not been examined the masterplan consultation was premature. 2. CBC’s narrative supporting Local Plan Policy SC2: Middlewick Ranges, acknowledges that the site is a designated Local Wildlife Site (LOW). (Previously LoWS’s were titled SINC’s – Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation, a more accurate description of their function). The CBC narrative adds “3.3.2 Middlewick Ranges is a Local Wildlife Site (LoWS) dominated by acid grassland primarily designated for this and its invertebrate populations, but with important scrub, scattered trees and copses and hedgerows. Birch Brook LoWS to the south of the site supports the brook itself and mixed broadleaf and wet woodland, with some characteristics of ancient woodland. The habitats within the site are of high (up to County) biodiversity value, including approximately 53 Ha of acid grassland. The site supports a range of protected species such as invertebrates, breeding birds and bats.” 3. An independent report by Midland Ecology which is an appendix to this submission identifies seven nationally threatened and eight nationally scarce species. 4. The Midland Ecology report paragraph 3.3 makes the point that an important function of Local Wildlife Sites is to “complement or buffer statutory conservation sites (SSSIs)”. -

Threatened Species Translocation Plan Button Wrinklewort (Rutidosis

Threatened Species Translocation Plan Button Wrinklewort (Rutidosis leptorrhynchoides) Summary Button wrinklewort Rutidosis leptorrhynchoides is a perennial wildflower that grows in grasslands and woodlands in Victoria, NSW and the ACT. There are only 29 known extant populations of the species left and only 8 that contain 5000 or more plants. The species is listed as endangered both nationally (EPBC Act 1999) and locally (Nature Conservation Act 2014). Increasing the number of populations through the establishment of new, self-sustaining populations is identified as a key management objective for the preservation of R. leptorrhynchoides in perpetuity in the wild (ACT Government 2017). The translocation will be undertaken at the Barrer Hill restoration area (Molonglo River Reserve, ACT). The restoration area supports potentially suitable habitat, is within the species known range and is believed to have supported R. leptorrhynchoides in the past. Furthermore, the Molonglo River Reserve is recognised as a biodiversity offset with significant and ongoing funding committed to the restoration, protection and ongoing management of reserve. Objectives To establish a new, self-sustaining, genetically diverse population of Rutidosis leptorrhynchoides within the Molonglo River Reserve that is capable of surviving in both the short and long term. Proponents Parks and Conservation Service (PCS) and Conservation Research (CR), Environment and Planning Directorate (EPD). Australian National Botanic Gardens (ANBG) Greening Australia (GA) Translocation team Richard Milner – Ecologist (PCS) Greg Baines – Senior vegetation ecologist (CR) Emma Cook – Vegetation ecologist (CR) David Taylor (ANBG) Martin Henery (ANBG) Nicki Taws (GA) Background Description The Button Wrinklewort Rutidosis leptorrhynchoides (Figure 1) is an erect perennial forb from the daisy family (Asteraceae). -

MULTIPLE SPECIES HABITAT CONSERVATION PLAN Annual Report 2015

Western Riverside County Regional Conservation Authority MULTIPLE SPECIES HABITAT CONSERVATION PLAN Annual Report 2015 Cover Description On February 27, 2015, the RCA acquired a property known as TNC/Monte Cristo. The project is located north of Avocado Mesa Road in the unincorporated Tenaja area of the County of Riverside. The property size is 22.92 acres and was purchased with State and Federal grant funding. The property is located within Rough Step Unit 5, MSHCP Criteria Cell number 7029, within Tenaja of the Southwest Area Plan. The vegetation for this property consists of grassland, coastal sage scrub, and woodland and forest habitat. Within this area, species known to exist, include California red-legged frog, Bell’s sage sparrow, Cooper’s hawk, grasshopper sparrow, bobcat and mountain lion. The property is adjacent to previously conserved lands on the south and east and connects to conserved lands to the north and west. Conservation of this land will help to assemble the reserve for this area, protecting important grassland and woodland forest habitats that are vital to many species. Western Riverside County MULTIPLE SPECIES HABITAT CONSERVATION PLAN ANNUAL REPORT For the Period January 1, 2015 through December 31, 2015 Submitted by the Western Riverside County Regional Conservation Authority TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................... ES-1 1.0 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................... -

Report on Rare Birds in Great Britain in 2011 Nigel Hudson and the Rarities Committee

Report on rare birds in Great Britain in 2011 Nigel Hudson and the Rarities Committee his is the 54th annual report of the to submit any well-documented older records British Birds Rarities Committee. The for consideration so that their true status can Tyear 2011 was an exceptional one for be reflected more clearly. As the previous rare birds, perhaps surpassed only by 2008 examples show, even records from more than for the range of taxa recorded. A number of 50 years ago can prove acceptable if suitable potential ‘firsts’ from 2011 are still under evidence is provided. consideration, including White-winged The rarest birds featured in this year’s Scoter Melanitta deglandi, Slaty-backed Gull report are as follows: Larus schistisagus, Asian Red-rumped 2nd Madeiran Petrel Oceanodroma castro, Swallow Cecropis daurica daurica/japonica Short-toed Eagle Circaetus gallicus and and Eastern Black Redstart Phoenicurus Eastern Crowned Warbler Phylloscopus ochruros phoenicuroides – but even in the coronatus absence of these mega rarities the report 3rd Purple Gallinule Porphyrio martinica, includes a mouth-watering variety of avian Siberian Blue Robin Larvivora cyane, strays from around the globe. The Eastern Rufous-tailed Robin L. sibilans and White- Black Redstarts are particularly interesting throated Robin Irania gutturalis because, in addition to considering the well- 4th Sandhill Crane Grus canadensis and watched birds in autumn 2011, we are American Black Tern Chlidonias niger reviewing a record from Kent in 1981. This surinamensis reassessment follows the provision of new images, showing details of the wing formula 5th Ovenbird Seiurus aurocapilla that were not available in the original sub- 5th & 6th Scarlet Tanager Piranga olivacea mission (see Brit. -

In Our Hands: the British and UKOT Species That Large Charitable Zoos & Aquariums Are Holding Back from Extinction (AICHI Target 12)

In our hands: The British and UKOT species that Large Charitable Zoos & Aquariums are holding back from extinction (AICHI target 12) We are: Clifton & West of England Zoological Society (Bristol Zoo, Wild Places) est. 1835 Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust (Jersey Zoo) est. 1963 East Midland Zoological Society (Twycross Zoo) est. 1963 Marwell Wildlife (Marwell Zoo) est. 1972 North of England Zoological Society (Chester Zoo) est. 1931 Royal Zoological Society of Scotland (Edinburgh Zoo, Highland Wildlife Park) est. 1913 The Deep est. 2002 Wild Planet Trust (Paignton Zoo, Living Coasts, Newquay Zoo) est. 1923 Zoological Society of London (ZSL London Zoo, ZSL Whipsnade Zoo) est. 1826 1. Wildcat 2. Great sundew 3. Mountain chicken 4. Red-billed chough 5. Large heath butterfly 6. Bermuda skink 7. Corncrake 8. Strapwort 9. Sand lizard 10. Llangollen whitebeam 11. White-clawed crayfish 12. Agile frog 13. Field cricket 14. Greater Bermuda snail 15. Pine hoverfly 16. Hazel dormouse 17. Maiden pink 18. Chagos brain coral 19. European eel 2 Executive Summary: There are at least 76 species native to the UK, Crown Dependencies, and British Overseas Territories which Large Charitable Zoos & Aquariums are restoring. Of these: There are 20 animal species in the UK & Crown Dependencies which would face significant declines or extinction on a global, national, or local scale without the action of our Zoos. There are a further 9 animal species in the British Overseas Territories which would face significant declines or extinction without the action of our Zoos. These species are all listed as threatened on the IUCN Red List. There are at least 19 UK animal species where the expertise of our Zoological Institutions is being used to assist with species recovery. -

Vot Salt), Presbyterians in a Union Service I N His Casterlin Is Traveling Salesman for the Hurry A

NO. 45. VOL. XXVII. MASON, MIOHIGAN, THUESDAY, NOVEMBER 6, 1902. Cut Mowers and plants for sale, Eille THE JUDGE DEMURRED. DIVIDED THE CITY. Beech, Maple street, Mason. *lp ..COPALINE. Charges Against Woodworth Not Tiic B. y. P, U, has adjourned Its HALL LUMBER COMPANY, LANSING. MICH. iu Proper Form. meeting at William Fanson's for one Democrats Carried It for Five Officers, It will make your Supervisor IT. K, Gunn of Delhi week. Rcpublicanj Got the Rest. came to Lan-sing this forenoon wltl We want the trade of eveiy Farmer in Ingham County antJ Oil Cloth or Linoleum Mixed Iron wanted, $4 ton, la lb. for we're making special inducements to get it Lumber is the report of the committee rubber. Weigh and pay at Cold .Stor• pointed by the board of supervisors As Nice as New. cheaper than ever at our yards and now is the time to buy. The Result In the Two Ward*. age. 45wSp. ... Abe Rkkdv, • to investigate a Hairs In the olllce of Restores and preserves the color.. A visit will prove this. All those indebted to us, please call the county clerk. Under instruction Is very durable. Will not and settle, as we need the nioiieyi In MiisoH tliere was a fairly strong from the board Mr. Gunn presented spot or crack. HALL LUMBER CO., LANSING, Michigan Ave. & M. C, e. R. 44w2 Weiui Lawi:e.n'CE, vote out, 555 taking advantage of the the report to Judge WIcst as a charge We liave |]|etit.y of room in our harn.s to sral)lo your liorses wliUu yon arc loadlDK, elective francliise. -

IPG Spring 2020 Birding Titles - December 2019 Page 1

Birding Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Hawaii Andre F. Raine, Helen Raine, Jack Jeffrey Summary This new book in the American Birding Association Field Guide Series includes complete coverage of all the major species, identification tips, and info on conservation status, habitat, and behaviors. Written by expert birders Helen & Andre F. Raine and filled with gorgeous color images by Jack Jeffrey, the American Birding Association Field Guide to Birds of Hawaii is the perfect companion for anyone wanting to learn more about the natural history and diversity of the state's birds, and when and where to see them. Contributor Bio Andre L. Raine, Ph.D . is the project coordinator of the Kaua’i Endangered Seabird Recovery Project in Kalaheo, Hawaii. Helen Raine is a writer and conservationist living in Kauai. Jack Jeffrey is a professional Scott & Nix, Inc. bird photographer, birding guide, and wildlife biologist. 9781935622710 Pub Date: 5/4/20 $24.95 USD Discount Code: LON Trade Paperback 272 Pages Carton Qty: 28 Nature / Birdwatching Guides NAT004000 Series: American Birding Association State Field 7.5 in H | 4.5 in W The Owl Calendar 2020 Jane Russ Summary An ideal gift for all owl lovers, this month-to-view wall calendar features 12 beautifully captured images of this ever-popular fixture of British wildlife. Supplied board-backed in a cello-bag with a hang tab. Each image is captioned by The Owl Book author Jane Russ, giving information and insight on their variety and characteristics. All Graffeg’s calendars are certified under the FSC system and are produced using materials Graffeg from sustainable sources. -

Molecular Approaches in Natural Resource Conservation and Management

MOLECULAR APPROACHES IN NATURAL RESOURCE CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT Recent advances in molecular genetics and genomics have been embraced by many scientists in natural resource conservation. Today, several major conservation and management journals are using the “genetics” editors of this book to deal solely with the influx of manuscripts that employ molecular data. The editors have attempted to synthesize some of the major uses of molecular markers in natural resource management in a book targeted not only at scientists but also at individuals actively making conservation and management decisions. To that end, the text features contributors who are major figures in molecular ecology and evolution – many having published books of their own. The aim is to direct and distill the thoughts of these outstanding scientists by compiling compelling case histories in molecular ecology as they apply to natural resource management. J. Andrew DeWoody is Professor of Genetics and University Faculty Scholar at Purdue University. He earned his MS in genetics at Texas A&M University and his PhD in zoology from Texas Tech University. His recent research in genetics, evolution, and ecology has been funded by organizations including the National Science Foundation, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Research Initiative, the Great Lakes Fishery Trust, and the National Geographic Society. His research is published in more than thirty-five journals, and he has served as Associate Editor for the North American Journal of Fisheries Management, the Journal of Wildlife Management,andGenetica. John W. Bickham is Professor in the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources (FNR) and Director of the Center for the Environment at Purdue University. -

Colorado Birds the Colorado Field Ornithologists’ Quarterly

Vol. 50 No. 4 Fall 2016 Colorado Birds The Colorado Field Ornithologists’ Quarterly Stealthy Streptopelias The Hungry Bird—Sun Spiders Separating Brown Creepers Colorado Field Ornithologists PO Box 929, Indian Hills, Colorado 80454 cfobirds.org Colorado Birds (USPS 0446-190) (ISSN 1094-0030) is published quarterly by the Col- orado Field Ornithologists, P.O. Box 929, Indian Hills, CO 80454. Subscriptions are obtained through annual membership dues. Nonprofit postage paid at Louisville, CO. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Colorado Birds, P.O. Box 929, Indian Hills, CO 80454. Officers and Directors of Colorado Field Ornithologists: Dates indicate end of cur- rent term. An asterisk indicates eligibility for re-election. Terms expire at the annual convention. Officers: President: Doug Faulkner, Arvada, 2017*, [email protected]; Vice Presi- dent: David Gillilan, Littleton, 2017*, [email protected]; Secretary: Chris Owens, Longmont, 2017*, [email protected]; Treasurer: Michael Kiessig, Indian Hills, 2017*, [email protected] Directors: Christy Carello, Golden, 2019; Amber Carver, Littleton, 2018*; Lisa Ed- wards, Palmer Lake, 2017; Ted Floyd, Lafayette, 2017; Gloria Nikolai, Colorado Springs, 2018*; Christian Nunes, Longmont, 2019 Colorado Bird Records Committee: Dates indicate end of current term. An asterisk indicates eligibility to serve another term. Terms expire 12/31. Chair: Mark Peterson, Colorado Springs, 2018*, [email protected] Committee Members: John Drummond, Colorado Springs, 2016; Peter Gent, Boul- der, 2017*; Tony Leukering, Largo, Florida, 2018; Dan Maynard, Denver, 2017*; Bill Schmoker, Longmont, 2016; Kathy Mihm Dunning, Denver, 2018* Past Committee Member: Bill Maynard Colorado Birds Quarterly: Editor: Scott W. Gillihan, [email protected] Staff: Christy Carello, science editor, [email protected]; Debbie Marshall, design and layout, [email protected] Annual Membership Dues (renewable quarterly): General $25; Youth (under 18) $12; Institution $30. -

Translocation of Imperiled Species Under Changing Climates

Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. ISSN 0077-8923 ANNALS OF THE NEW YORK ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Issue: The Year in Ecology and Conservation Biology Translocation of imperiled species under changing climates Mark W. Schwartz1 and Tara G. Martin2 1John Muir Institute of the Environment, University of California, Davis, California. 2Climate Adaptation Flagship, CSIRO Ecosystem Sciences, Ecoscience Precinct, Queensland, Australia Address for correspondence: Mark W. Schwartz, Department of Environmental Science & Policy, 1 Shields Avenue, University of California, Davis, CA 95616. [email protected] Conservation translocation of species varies from restoring historic populations to managing the relocation of imperiled species to new locations. We review the literature in three areas—translocation, managed relocation, and conservation decision making—to inform conservation translocation under changing climates. First, climate change increases the potential for conflict over both the efficacy and the acceptability of conservation translocation. The emerging literature on managed relocation highlights this discourse. Second, conservation translocation works in concert with other strategies. The emerging literature in structured decision making provides a framework for prioritizing conservation actions—considering many possible alternatives that are evaluated based on expected benefit, risk, and social–political feasibility. Finally, the translocation literature has historically been primarily concerned with risks associated with the target species. In contrast, -

Movers and Stayers: Novel Assemblages in Changing Environments

Hobbs, R.J., Valentine, L.E., Standish, R.J., & S.T. Jackson (2017) Movers and Stayers: Novel Assemblages in Changing Environments. Trends in Ecology and Evolution: Volume 33, Issue 2, 116 – 128. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2017.11.001 © 2017. This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 1 1 Movers and stayers: novel assemblages in changing environments 2 3 Richard J Hobbs1, Leonie E. Valentine1, Rachel J. Standish2, Stephen T. Jackson3 4 1 School of Biological Science, University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia 5 2 School of Veterinary and Life Sciences, Murdoch University, Murdoch, WA 6150, Australia 6 3 U.S. Geological Survey, DOI Southwest Climate Science Center, 1064 E. Lowell Street, Tucson, 7 AZ 85721, USA and Department of Geosciences and School of Natural Resources and 8 Environment, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721 USA 9 10 Corresponding Author: Hobbs, R.J. ([email protected]) 11 12 Keywords: range shifts; species persistence; place-based conservation; novel assemblages 2 13 14 15 Increased attention to species movement in response to environmental change highlights the need to 16 consider changes in species distributions and altered biological assemblages. Such changes are well 17 known from paleoecological studies, but have accelerated with ongoing pervasive human influence. 18 In addition to species that move, some species will stay put, leading to an array of novel 19 interactions. Species show a variety of responses that can allow movement or persistence. -

Cherrywood SDZ Biodiversity Plan with Cover (Pdf

Biodiversity Plan Cherrywood Strategic Development Zone: Biodiversity Plan Contents 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 2. SUMMARY OF ECOLOGICAL FEATURES IN THE SDZ AREA AND ENVIRONS ....................... 2 2.1 Desktop Review and Field Surveys .................................................... 2 2.2 Habitats List ................................................................................... 2 2.3 Eutrophic lake ................................................................................ 3 2.4 Other artificial lakes and ponds ......................................................... 3 2.5 Eroding upland rivers ...................................................................... 4 2.6 Depositing lowland rivers ................................................................. 4 2.7 Drainage ditches ............................................................................. 4 2.8 Calcareous Springs .......................................................................... 5 2.9 Reed and Large Sedge Swamps ........................................................ 6 2.10 Tall-herb swamp ............................................................................. 6 2.11 Improved agricultural grassland ........................................................ 7 2.12 Amenity Grassland .......................................................................... 8 2.13 Dry calcareous and neutral grassland ...............................................