Polytopes, Their Diameter, and Randomized Simplex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geometry of Generalized Permutohedra

Geometry of Generalized Permutohedra by Jeffrey Samuel Doker A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Mathematics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Federico Ardila, Co-chair Lior Pachter, Co-chair Matthias Beck Bernd Sturmfels Lauren Williams Satish Rao Fall 2011 Geometry of Generalized Permutohedra Copyright 2011 by Jeffrey Samuel Doker 1 Abstract Geometry of Generalized Permutohedra by Jeffrey Samuel Doker Doctor of Philosophy in Mathematics University of California, Berkeley Federico Ardila and Lior Pachter, Co-chairs We study generalized permutohedra and some of the geometric properties they exhibit. We decompose matroid polytopes (and several related polytopes) into signed Minkowski sums of simplices and compute their volumes. We define the associahedron and multiplihe- dron in terms of trees and show them to be generalized permutohedra. We also generalize the multiplihedron to a broader class of generalized permutohedra, and describe their face lattices, vertices, and volumes. A family of interesting polynomials that we call composition polynomials arises from the study of multiplihedra, and we analyze several of their surprising properties. Finally, we look at generalized permutohedra of different root systems and study the Minkowski sums of faces of the crosspolytope. i To Joe and Sue ii Contents List of Figures iii 1 Introduction 1 2 Matroid polytopes and their volumes 3 2.1 Introduction . .3 2.2 Matroid polytopes are generalized permutohedra . .4 2.3 The volume of a matroid polytope . .8 2.4 Independent set polytopes . 11 2.5 Truncation flag matroids . 14 3 Geometry and generalizations of multiplihedra 18 3.1 Introduction . -

Two Poset Polytopes

Discrete Comput Geom 1:9-23 (1986) G eometrv)i.~.reh, ~ ( :*mllmlati~ml © l~fi $1~ter-Vtrlq New Yorklu¢. t¢ Two Poset Polytopes Richard P. Stanley* Department of Mathematics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139 Abstract. Two convex polytopes, called the order polytope d)(P) and chain polytope <~(P), are associated with a finite poset P. There is a close interplay between the combinatorial structure of P and the geometric structure of E~(P). For instance, the order polynomial fl(P, m) of P and Ehrhart poly- nomial i(~9(P),m) of O(P) are related by f~(P,m+l)=i(d)(P),m). A "transfer map" then allows us to transfer properties of O(P) to W(P). In particular, we transfer known inequalities involving linear extensions of P to some new inequalities. I. The Order Polytope Our aim is to investigate two convex polytopes associated with a finite partially ordered set (poset) P. The first of these, which we call the "order polytope" and denote by O(P), has been the subject of considerable scrutiny, both explicit and implicit, Much of what we say about the order polytope will be essentially a review of well-known results, albeit ones scattered throughout the literature, sometimes in a rather obscure form. The second polytope, called the "chain polytope" and denoted if(P), seems never to have been previously considered per se. It is a special case of the vertex-packing polytope of a graph (see Section 2) but has many special properties not in general valid or meaningful for graphs. -

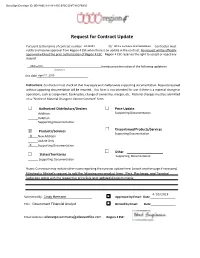

Request for Contract Update

DocuSign Envelope ID: 0E48A6C9-4184-4355-B75C-D9F791DFB905 Request for Contract Update Pursuant to the terms of contract number________________R142201 for _________________________ Office Furniture and Installation Contractor must notify and receive approval from Region 4 ESC when there is an update in the contract. No request will be officially approved without the prior authorization of Region 4 ESC. Region 4 ESC reserves the right to accept or reject any request. Allsteel Inc. hereby provides notice of the following update on (Contractor) this date April 17, 2019 . Instructions: Contractor must check all that may apply and shall provide supporting documentation. Requests received without supporting documentation will be returned. This form is not intended for use if there is a material change in operations, such as assignment, bankruptcy, change of ownership, merger, etc. Material changes must be submitted on a “Notice of Material Change to Vendor Contract” form. Authorized Distributors/Dealers Price Update Addition Supporting Documentation Deletion Supporting Documentation Discontinued Products/Services X Products/Services Supporting Documentation X New Addition Update Only X Supporting Documentation Other States/Territories Supporting Documentation Supporting Documentation Notes: Contractor may include other notes regarding the contract update here: (attach another page if necessary). Attached is Allsteel's request to add the following new product lines: Park, Recharge, and Townhall Collection along with the respective price -

![The Geometry of Nim Arxiv:1109.6712V1 [Math.CO] 30](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8642/the-geometry-of-nim-arxiv-1109-6712v1-math-co-30-48642.webp)

The Geometry of Nim Arxiv:1109.6712V1 [Math.CO] 30

The Geometry of Nim Kevin Gibbons Abstract We relate the Sierpinski triangle and the game of Nim. We begin by defining both a new high-dimensional analog of the Sierpinski triangle and a natural geometric interpretation of the losing positions in Nim, and then, in a new result, show that these are equivalent in each finite dimension. 0 Introduction The Sierpinski triangle (fig. 1) is one of the most recognizable figures in mathematics, and with good reason. It appears in everything from Pascal's Triangle to Conway's Game of Life. In fact, it has already been seen to be connected with the game of Nim, albeit in a very different manner than the one presented here [3]. A number of analogs have been discovered, such as the Menger sponge (fig. 2) and a three-dimensional version called a tetrix. We present, in the first section, a generalization in higher dimensions differing from the more typical simplex generalization. Rather, we define a discrete Sierpinski demihypercube, which in three dimensions coincides with the simplex generalization. In the second section, we briefly review Nim and the theory behind optimal play. As in all impartial games (games in which the possible moves depend only on the state of the game, and not on which of the two players is moving), all possible positions can be divided into two classes - those in which the next player to move can force a win, called N-positions, and those in which regardless of what the next player does the other player can force a win, called P -positions. -

Notes Has Not Been Formally Reviewed by the Lecturer

6.896 Topics in Algorithmic Game Theory February 22, 2010 Lecture 6 Lecturer: Constantinos Daskalakis Scribe: Jason Biddle, Debmalya Panigrahi NOTE: The content of these notes has not been formally reviewed by the lecturer. It is recommended that they are read critically. In our last lecture, we proved Nash's Theorem using Broweur's Fixed Point Theorem. We also showed Brouwer's Theorem via Sperner's Lemma in 2-d using a limiting argument to go from the discrete combinatorial problem to the topological one. In this lecture, we present a multidimensional generalization of the proof from last time. Our proof differs from those typically found in the literature. In particular, we will insist that each step of the proof be constructive. Using constructive arguments, we shall be able to pin down the complexity-theoretic nature of the proof and make the steps algorithmic in subsequent lectures. In the first part of our lecture, we present a framework for the multidimensional generalization of Sperner's Lemma. A Canonical Triangulation of the Hypercube • A Legal Coloring Rule • In the second part, we formally state Sperner's Lemma in n dimensions and prove it using the following constructive steps: Colored Envelope Construction • Definition of the Walk • Identification of the Starting Simplex • Direction of the Walk • 1 Framework Recall that in the 2-dimensional case we had a square which was divided into triangles. We had also defined a legal coloring scheme for the triangle vertices lying on the boundary of the square. Now let us extend those concepts to higher dimensions. 1.1 Canonical Triangulation of the Hypercube We begin by introducing the n-simplex as the n-dimensional analog of the triangle in 2 dimensions as shown in Figure 1. -

1 Lifts of Polytopes

Lecture 5: Lifts of polytopes and non-negative rank CSE 599S: Entropy optimality, Winter 2016 Instructor: James R. Lee Last updated: January 24, 2016 1 Lifts of polytopes 1.1 Polytopes and inequalities Recall that the convex hull of a subset X n is defined by ⊆ conv X λx + 1 λ x0 : x; x0 X; λ 0; 1 : ( ) f ( − ) 2 2 [ ]g A d-dimensional convex polytope P d is the convex hull of a finite set of points in d: ⊆ P conv x1;:::; xk (f g) d for some x1;:::; xk . 2 Every polytope has a dual representation: It is a closed and bounded set defined by a family of linear inequalities P x d : Ax 6 b f 2 g for some matrix A m d. 2 × Let us define a measure of complexity for P: Define γ P to be the smallest number m such that for some C s d ; y s ; A m d ; b m, we have ( ) 2 × 2 2 × 2 P x d : Cx y and Ax 6 b : f 2 g In other words, this is the minimum number of inequalities needed to describe P. If P is full- dimensional, then this is precisely the number of facets of P (a facet is a maximal proper face of P). Thinking of γ P as a measure of complexity makes sense from the point of view of optimization: Interior point( methods) can efficiently optimize linear functions over P (to arbitrary accuracy) in time that is polynomial in γ P . ( ) 1.2 Lifts of polytopes Many simple polytopes require a large number of inequalities to describe. -

Interval Vector Polytopes

Interval Vector Polytopes By Gabriel Dorfsman-Hopkins SENIOR HONORS THESIS ROSA C. ORELLANA, ADVISOR DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS DARTMOUTH COLLEGE JUNE, 2013 Contents Abstract iv 1 Introduction 1 2 Preliminaries 4 2.1 Convex Polytopes . 4 2.2 Lattice Polytopes . 8 2.2.1 Ehrhart Theory . 10 2.3 Faces, Face Lattices and the Dual . 12 2.3.1 Faces of a Polytope . 12 2.3.2 The Face Lattice of a Polytope . 15 2.3.3 Duality . 18 2.4 Basic Graph Theory . 22 3IntervalVectorPolytopes 23 3.1 The Complete Interval Vector Polytope . 25 3.2 TheFixedIntervalVectorPolytope . 30 3.2.1 FlowDimensionGraphs . 31 4TheIntervalPyramid 38 ii 4.1 f-vector of the Interval Pyramid . 40 4.2 Volume of the Interval Pyramid . 45 4.3 Duality of the Interval Pyramid . 50 5 Open Questions 57 5.1 Generalized Interval Pyramid . 58 Bibliography 60 iii Abstract An interval vector is a 0, 1 -vector where all the ones appear consecutively. An { } interval vector polytope is the convex hull of a set of interval vectors in Rn.Westudy several classes of interval vector polytopes which exhibit interesting combinatorial- geometric properties. In particular, we study a class whose volumes are equal to the catalan numbers, another class whose legs always form a lattice basis for their affine space, and a third whose face numbers are given by the pascal 3-triangle. iv Chapter 1 Introduction An interval vector is a 0, 1 -vector in Rn such that the ones (if any) occur consecu- { } tively. These vectors can nicely and discretely model scheduling problems where they represent the length of an uninterrupted activity, and so understanding the combi- natorics of these vectors is useful in optimizing scheduling problems of continuous activities of certain lengths. -

Understanding the Formation of Pbse Honeycomb Superstructures by Dynamics Simulations

PHYSICAL REVIEW X 9, 021015 (2019) Understanding the Formation of PbSe Honeycomb Superstructures by Dynamics Simulations Giuseppe Soligno* and Daniel Vanmaekelbergh Condensed Matter and Interfaces, Debye Institute for Nanomaterials Science, Utrecht University, Princetonplein 1, Utrecht 3584 CC, Netherlands (Received 28 October 2018; revised manuscript received 28 January 2019; published 23 April 2019) Using a coarse-grained molecular dynamics model, we simulate the self-assembly of PbSe nanocrystals (NCs) adsorbed at a flat fluid-fluid interface. The model includes all key forces involved: NC-NC short- range facet-specific attractive and repulsive interactions, entropic effects, and forces due to the NC adsorption at fluid-fluid interfaces. Realistic values are used for the input parameters regulating the various forces. The interface-adsorption parameters are estimated using a recently introduced sharp- interface numerical method which includes capillary deformation effects. We find that the final structure in which the NCs self-assemble is drastically affected by the input values of the parameters of our coarse- grained model. In particular, by slightly tuning just a few parameters of the model, we can induce NC self- assembly into either silicene-honeycomb superstructures, where all NCs have a f111g facet parallel to the fluid-fluid interface plane, or square superstructures, where all NCs have a f100g facet parallel to the interface plane. Both of these nanostructures have been observed experimentally. However, it is still not clear their formation mechanism, and, in particular, which are the factors directing the NC self-assembly into one or another structure. In this work, we identify and quantify such factors, showing illustrative assembled-phase diagrams obtained from our simulations. -

Revised Primal Simplex Method Katta G

6.1 Revised Primal Simplex method Katta G. Murty, IOE 510, LP, U. Of Michigan, Ann Arbor First put LP in standard form. This involves floowing steps. • If a variable has only a lower bound restriction, or only an upper bound restriction, replace it by the corresponding non- negative slack variable. • If a variable has both a lower bound and an upper bound restriction, transform lower bound to zero, and list upper bound restriction as a constraint (for this version of algorithm only. In bounded variable simplex method both lower and upper bound restrictions are treated as restrictions, and not as constraints). • Convert all inequality constraints as equations by introducing appropriate nonnegative slack for each. • If there are any unrestricted variables, eliminate each of them one by one by performing a pivot step. Each of these reduces no. of variables by one, and no. of constraints by one. This 128 is equivalent to having them as permanent basic variables in the tableau. • Write obj. in min form, and introduce it as bottom row of original tableau. • Make all RHS constants in remaining constraints nonnega- tive. 0 Example: Max z = x1 − x2 + x3 + x5 subject to x1 − x2 − x4 − x5 ≥ 2 x2 − x3 + x5 + x6 ≤ 11 x1 + x2 + x3 − x5 =14 −x1 + x4 =6 x1 ≥ 1;x2 ≤ 1; x3;x4 ≥ 0; x5;x6 unrestricted. 129 Revised Primal Simplex Algorithm With Explicit Basis Inverse. INPUT NEEDED: Problem in standard form, original tableau, and a primal feasible basic vector. Original Tableau x1 ::: xj ::: xn −z a11 ::: a1j ::: a1n 0 b1 . am1 ::: amj ::: amn 0 bm c1 ::: cj ::: cn 1 α Initial Setup: Let xB be primal feasible basic vector and Bm×m be associated basis. -

Uniform Polychora

BRIDGES Mathematical Connections in Art, Music, and Science Uniform Polychora Jonathan Bowers 11448 Lori Ln Tyler, TX 75709 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Like polyhedra, polychora are beautiful aesthetic structures - with one difference - polychora are four dimensional. Although they are beyond human comprehension to visualize, one can look at various projections or cross sections which are three dimensional and usually very intricate, these make outstanding pieces of art both in model form or in computer graphics. Polygons and polyhedra have been known since ancient times, but little study has gone into the next dimension - until recently. Definitions A polychoron is basically a four dimensional "polyhedron" in the same since that a polyhedron is a three dimensional "polygon". To be more precise - a polychoron is a 4-dimensional "solid" bounded by cells with the following criteria: 1) each cell is adjacent to only one other cell for each face, 2) no subset of cells fits criteria 1, 3) no two adjacent cells are corealmic. If criteria 1 fails, then the figure is degenerate. The word "polychoron" was invented by George Olshevsky with the following construction: poly = many and choron = rooms or cells. A polytope (polyhedron, polychoron, etc.) is uniform if it is vertex transitive and it's facets are uniform (a uniform polygon is a regular polygon). Degenerate figures can also be uniform under the same conditions. A vertex figure is the figure representing the shape and "solid" angle of the vertices, ex: the vertex figure of a cube is a triangle with edge length of the square root of 2. -

Chapter 6: Gradient-Free Optimization

AA222: MDO 133 Monday 30th April, 2012 at 16:25 Chapter 6 Gradient-Free Optimization 6.1 Introduction Using optimization in the solution of practical applications we often encounter one or more of the following challenges: • non-differentiable functions and/or constraints • disconnected and/or non-convex feasible space • discrete feasible space • mixed variables (discrete, continuous, permutation) • large dimensionality • multiple local minima (multi-modal) • multiple objectives Gradient-based optimizers are efficient at finding local minima for high-dimensional, nonlinearly- constrained, convex problems; however, most gradient-based optimizers have problems dealing with noisy and discontinuous functions, and they are not designed to handle multi-modal problems or discrete and mixed discrete-continuous design variables. Consider, for example, the Griewank function: n n x2 f(x) = P i − Q cos pxi + 1 4000 i i=1 i=1 (6.1) −600 ≤ xi ≤ 600 Mixed (Integer-Continuous) Figure 6.1: Graphs illustrating the various types of functions that are problematic for gradient- based optimization algorithms AA222: MDO 134 Monday 30th April, 2012 at 16:25 Figure 6.2: The Griewank function looks deceptively smooth when plotted in a large domain (left), but when you zoom in, you can see that the design space has multiple local minima (center) although the function is still smooth (right) How we could find the best solution for this example? • Multiple point restarts of gradient (local) based optimizer • Systematically search the design space • Use gradient-free optimizers Many gradient-free methods mimic mechanisms observed in nature or use heuristics. Unlike gradient-based methods in a convex search space, gradient-free methods are not necessarily guar- anteed to find the true global optimal solutions, but they are able to find many good solutions (the mathematician's answer vs. -

The Simplex Algorithm in Dimension Three1

The Simplex Algorithm in Dimension Three1 Volker Kaibel2 Rafael Mechtel3 Micha Sharir4 G¨unter M. Ziegler3 Abstract We investigate the worst-case behavior of the simplex algorithm on linear pro- grams with 3 variables, that is, on 3-dimensional simple polytopes. Among the pivot rules that we consider, the “random edge” rule yields the best asymptotic behavior as well as the most complicated analysis. All other rules turn out to be much easier to study, but also produce worse results: Most of them show essentially worst-possible behavior; this includes both Kalai’s “random-facet” rule, which is known to be subexponential without dimension restriction, as well as Zadeh’s de- terministic history-dependent rule, for which no non-polynomial instances in general dimensions have been found so far. 1 Introduction The simplex algorithm is a fascinating method for at least three reasons: For computa- tional purposes it is still the most efficient general tool for solving linear programs, from a complexity point of view it is the most promising candidate for a strongly polynomial time linear programming algorithm, and last but not least, geometers are pleased by its inherent use of the structure of convex polytopes. The essence of the method can be described geometrically: Given a convex polytope P by means of inequalities, a linear functional ϕ “in general position,” and some vertex vstart, 1Work on this paper by Micha Sharir was supported by NSF Grants CCR-97-32101 and CCR-00- 98246, by a grant from the U.S.-Israeli Binational Science Foundation, by a grant from the Israel Science Fund (for a Center of Excellence in Geometric Computing), and by the Hermann Minkowski–MINERVA Center for Geometry at Tel Aviv University.