Graduation Final Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

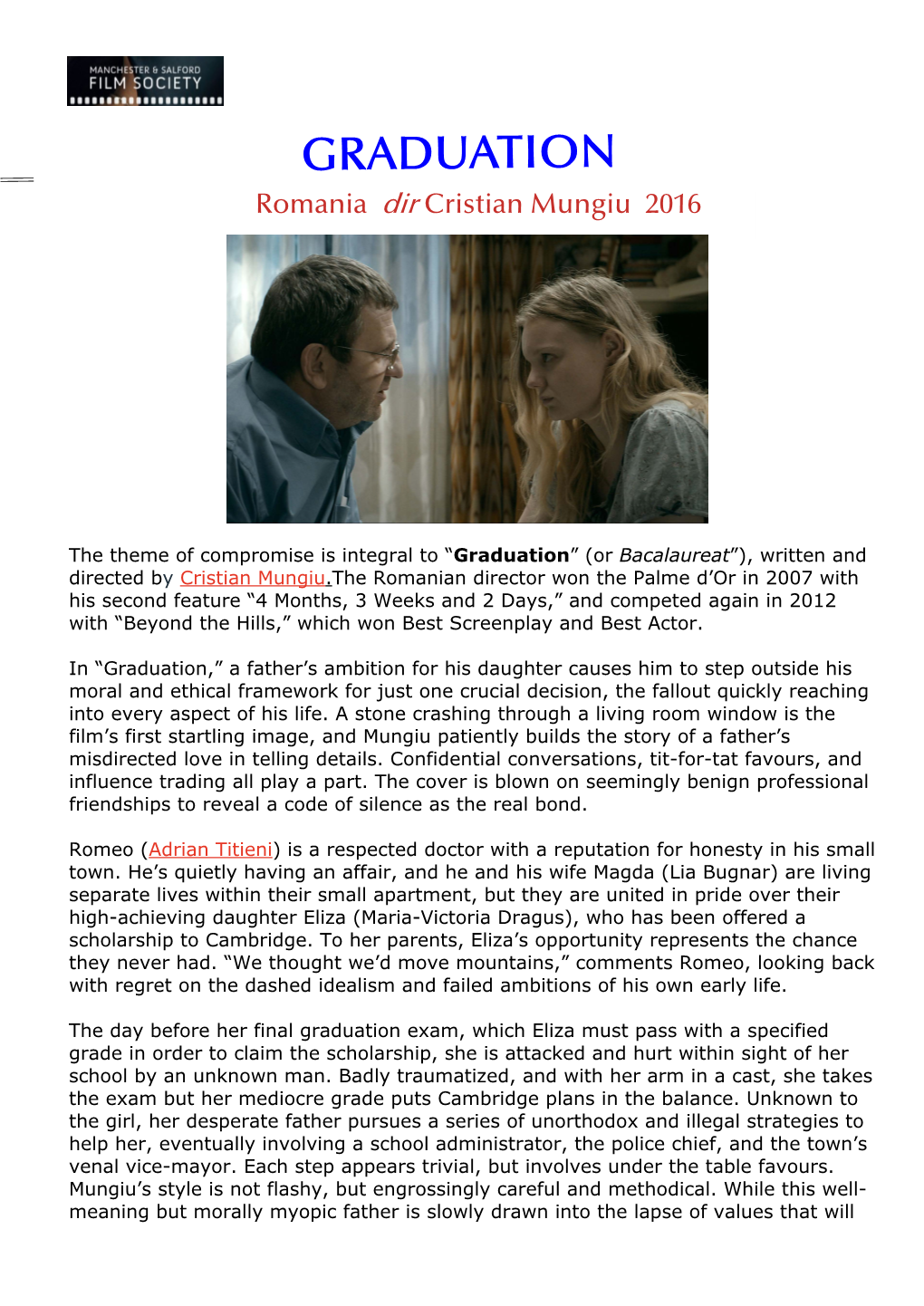

Recommended publications

-

Factsheet MEDIA Success Stories

Factsheet MEDIA success stories Saul Fia (Son of Saul, 2015) directed by László Nemes (HU) Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film Grand Prix at Cannes Film Festival Support: € 697,585 for its distribution across Europe Son of Saul is a small-budget film – €1.5 million. MEDIA decided to back the project and contributed to distributed it in 24 countries across Europe – a record on its own. La Grande Bellezza (The Great Beauty, 2013) directed by Paolo Sorrentino (IT) Oscar and Golden Globe for Best Foreign Language Film Support: € 491,531 for its development and its distribution across Europe With La Grande Bellezza, Paolo Sorrentino gained international acclaim as a European director who could encapsulate the human dimension of his characters in a perfect shot. Youth (also funded by MEDIA) continued along the same path. In 2016, Sorrentino made a successful foray into television, with The Young Pope which he considers to be a 10 hour-long movie Ida (2013) directed by Pawel Pawlikowski (PL) Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film Lux Prize Support: € 646,282 for its development and its distribution across Europe MEDIA provided seed money for the development of Ida. It also helped foreign distributors to show the film abroad through distribution schemes: Memento Films in France received €29,000 to show Ida to French audiences. France had the highest proportion of admissions for the film across Europe, with 484,000 viewers, one third of its total admissions. Tabu (2012) directed by Miguel Gomes (PT) 18 prizes and 40 nominations Support: € 192,800 for its development and its distribution across Europe Tabu, by Portugese director Miguel Gomes, was developed with the support of MEDIA. -

CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS of FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and Counting…

5 JAN 18 1 FEB 18 1 | 5 JAN 18 - 1 FEB 18 88 LOTHIAN ROAD | FILMHOUSECinema.COM CELEBRATING FORTY YEARS OF FILMS WORTH TALKING ABOUT 39 Years, 2 Months, and counting… As you’ll spot deep within this programme (and hinted at on the front cover) January 2018 sees the start of a series of films that lead up to celebrations in October marking the 40th birthday of Filmhouse as a public cinema on Lothian Road. We’ve chosen to screen a film from every year we’ve been bringing the very best cinema to the good people of Edinburgh, and while it is tremendous fun looking back through the history of what has shown here, it was quite an undertaking going through all the old programmes and choosing what to show, and a bit of a personal journey for me as one who started coming here as a customer in the mid-80s (I know, I must have started very young...). At that time, I’d no idea that Filmhouse had only been in existence for less than 10 years – it seemed like such an established, essential institution and impossible to imagine it not existing in a city such as Edinburgh. My only hope is that the cinema is as important today as I felt it was then, and that the giants on whose shoulders we currently stand feel we’re worthy of their legacy. I hope you can join us for at least some of the screenings on this trip down memory lane... And now, back to the now. -

Sight & Sound Films of 2007

Sight & Sound Films of 2007 Each year we ask a selection of our contributors - reviewers and critics from around the world - for their five films of the year. It's a very loosely policed subjective selection, based on films the writer has seen and enjoyed that year, and we don't deny them the choice of films that haven't yet reached the UK. And we don't give them much time to ponder, either - just about a week. So below you'll find the familiar and the obscure, the new and the old. From this we put together the top ten you see here. What distinguishes this particular list is that it's been drawn up from one of the best years for all-round quality I can remember. 2007 has seen some extraordinary films. So all of the films in the ten are must-sees and so are many more. Enjoy. - Nick James, Editor. 1 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Cristian Mungiu) 2 Inland Empire (David Lynch) 3 Zodiac (David Fincher) = 4 I’m Not There (Todd Haynes) The Lives of Others (Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck) 6 Silent Light (Carlos Reygadas) = 7 The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (Andrew Dominik) Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul) No Country for Old Men (Ethan and Joel Coen) Eastern Promises (David Cronenberg) 1 Table of Contents – alphabetical by critic Gilbert Adair (Critic and author, UK)............................................................................................4 Kaleem Aftab (Critic, The Independent, UK)...............................................................................4 Geoff Andrew (Critic -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

Columbia Filmcolumbia Is Grateful to the Following Sponsors for Their Generous Support

O C T O B E R 1 8 – 2 7 , 2 0 1 9 20 TH ANNIVERSARY FILM COLUMBIA FILMCOLUMBIA IS GRATEFUL TO THE FOLLOWING SPONSORS FOR THEIR GENEROUS SUPPORT BENEFACTOR EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS 20 TH PRODUCERS FILM COLUMBIA FESTIVAL SPONSORS MEDIA PARTNERS OCTOBER 18–27, 2019 | CHATHAM, NEW YORK Programs of the Crandell Theatre are made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Gov. Andrew Cuomo and the New York filmcolumbia.org State Legislature. 5 VENUES AND SCHEDULE 9 CRANDELL THEATRE VENUES AND SCHEDULE 11 20th FILMCOLUMBIA CRANDELL THEATRE 48 Main Street, Chatham 13 THE FILMS á Friday, October 18 56 PERSONNEL 1:00pm ADAM (page 15) 56 DONORS 4:00pm THE ICE STORM (page 15) á Saturday, October 19 74 ORDER TICKETS 12:00 noon DRIVEWAYS (page 16) 2:30pm CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON (page 17) á Sunday, October 20 11:00am QUEEN OF HEARTS: AUDREY FLACK (page 18) 1:00pm GIVE ME LIBERTY (page 18 3:30pm THE VAST OF NIGHT (page 19) 5:30pm ZOMBI CHILD (page 19) 7:30pm FRANKIE + DESIGN IN MIND: ON LOCATION WITH JAMES IVORY (short) (page 20) á Monday, October 21 11:30am THE TROUBLE WITH YOU (page 21) 1:30pm SYNONYMS (page 21) 4:00pm VARDA BY AGNÈS (page 22) 6:30pm SORRY WE MISSED YOU (page 22) 8:30pm PARASITE (page 23) á Tuesday, October 22 12:00 noon ICE ON FIRE (page 24) 2:00pm SOUTH MOUNTAIN (page 24) 4:00pm CUNNINGHAM (page 25) 6:00pm THE CHAMBERMAID (page 26) 8:15pm THE SONG OF NAMES (page 27) á Wednesday, October 23 11:30am SEW THE WINTER TO MY SKIN (page 28) 2:00pm MICKEY AND THE BEAR (page 28) 3:45pm CLEMENCY (page 29) 6:00pm -

C a H Ie R P É D a G O G Iq

Cahier pédagogique IFI Education l a e u g v a é m l o i n “nos sociétés starifient l’individu.” jEan -PiErrE dardEnnE cO -réalisatEur les Personnages 1. Avant le film Regardez l’affiche du film ci-contre et répondez aux questions ci-dessous. a) Après avoir vu Le gamin au vélo c) D’après vous l’affiche tente pensez-vous que l’affiche est une d’attirer quelle audience bonne représentation du film? pour ce film? b) Pourquoi ce cadre de la photo a-t-il été choisi? 2. Les Personnages Principaux s s u u n n e e l l P P e e n n i i t t s s i i r r h h C C © © Guy Wes Cyril Samantha a) Regardez les photos. Écrivez une description de chaque caractère. Ensuite comparez chaque personnage avec une autre du film. Utilisez les phrases et les adjectifs ci-dessous. Par exemple Cyril a l’air têtu. Il est mineur par contre Guy est adulte. Adjectifs hostile Des phrases utiles ensif compréh te malhonnê actif ux • Il / Elle a l’air… chaleure t têtu charman x • Je dirais qu’elle/il est _______ car _______ paresseu t distant accueillan • Il me semble qu’il / elle est impoli nête • Il est _______ par contre elle est _______ hon • Au début il est _______ mais à la fin il est _______ 3. Résumé 4. Expression écrite Trouvez la bonne terminaison de chaque phrase pour complétez le résumé ci-dessous. Écrivez les phrases complètes dans votre cahier. -

Festival Review 72Nd Festival De Cannes Finding Faith in Film

Joel Mayward Festival Review 72nd Festival de Cannes Finding Faith in Film While standing in the lengthy queues at the 2019 Festival de Cannes, I would strike up conversations with fellow film critics from around the world to discuss the films we had experienced. During the dialogue, I would express my interests and background: I am both a film critic and a theologian, and thus intrigued by the rich connections between theology and cinema. To which my interlocutor would inevitably raise an eyebrow and reply, “How are those two subjects even related?” Yet every film I saw at Cannes somehow addressed the question of God, religion or spirituality. Indeed, I was struck by how the most famous and most glamorous film festival in the Western world was a God-haunted environ- ment where religion was present both on- and off-screen. As I viewed films in competition for the Palme d’Or, as well as from the Un Certain Regard, Direc- tors’ Fortnight and Critics’ Week selections, I offer brief reviews and reflections on the religious dimension of Cannes 2019.1 SUBTLE AND SUPERFLUOUS SPIRITUALITY Sometimes the presence of religion was subtle or superfluous. For example, in the perfectly bonkers Palme d’Or winner, Gisaengchung (Parasite, Bong Joon- Ho, KR 2019), characters joke about delivering pizzas to a megachurch in Seoul. Or there’s Bill Murray’s world-weary police officer crossing himself and exclaim- ing (praying?), “Holy fuck, God help us” as zombie hordes bear down on him and Adam Driver in The Dead Don’t Die (Jim Jarmusch, US 2019). -

Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND Index 2016_4.indd 1 14/12/2016 17:41 SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 7:25 (magazine) 9:102 7:43; 10:47; 11:41 Orlando 6:112 effect on technological Film review titles are also Agace, Mel 1:15 American Film Institute (AFI) 3:53 Apologies 2:54 Ran 4:7; 6:94-5; 9:111 changes 8:38-43 included and are indicated by age and cinema American Friend, The 8:12 Appropriate Behaviour 1:55 Jacques Rivette 3:38, 39; 4:5, failure to cater for and represent (r) after the reference; growth in older viewers and American Gangster 11:31, 32 Aquarius (2016) 6:7; 7:18, Céline and Julie Go Boating diversity of in 2015 1:55 (b) after reference indicates their preferences 1:16 American Gigolo 4:104 20, 23; 10:13 1:103; 4:8, 56, 57; 5:52, missing older viewers, growth of and A a book review Agostini, Philippe 11:49 American Graffiti 7:53; 11:39 Arabian Nights triptych (2015) films of 1970s 3:94-5, Paris their preferences 1:16 Aguilar, Claire 2:16; 7:7 American Honey 6:7; 7:5, 18; 1:46, 49, 53, 54, 57; 3:5: nous appartient 4:56-7 viewing films in isolation, A Aguirre, Wrath of God 3:9 10:13, 23; 11:66(r) 5:70(r), 71(r); 6:58(r) Eric Rohmer 3:38, 39, 40, pleasure of 4:12; 6:111 Aaaaaaaah! 1:49, 53, 111 Agutter, Jenny 3:7 background -

NUOVO CINEMA Rumenoper

NUOVO CINEMA RUMENO 2 febbraio - 4 marzo 2009 Da qualche anno il cinema rumeno ottiene prestigiosi riconoscimenti nei maggiori festival internazionali. Sicuramente è improprio parlare di una “Nouvelle vague” che da Bucarest fa sentire la sua voce e attira l’attenzione del mondo intero, anche perché prima non esisteva nessuna “Vieille vague”, ma c’erano solo degli autori isolati, il più importante dei quali è stato sicuramente Lucian Pintilie, regista maledetto messo all’indice dal regime di Ceausescu. Ma è vero che, in questo primo scorcio del nuovo millennio, dalla Romania ci sono giunti diversi film indipendenti di alto valore, che hanno contribuito alla riflessione sul periodo buio della dittatura e sulla fragile democrazia post-rivoluzionaria. I quattro film che presentiamo vogliono essere un assaggio e una testimonianza di questa innegabile realtà. 1 PROGRAMMA Circolo del cinema Bellinzona Cinema Forum 1+2 mar 3 febbraio, 20.30 COME HO VISSUTO LA FINE DEL MONDO Cum mi-am petrecut sfirsitul lumii di Catalin Mitulescu, Romania 2006 sab 7 febbraio, 18.00 4 MESI, 3 SETTIMANE E 2 GIORNI 4 luni, 3 saptamani si 2 zile di Cristian Mungiu, Romania 2007 mar 10 febbraio, 20.30 LA MORTE DEL SIGNOR LAZARESCU Moartea Domnului Lazarescu di Cristi Puiu, Romania 2005 sab 17 febbraio, 18.00 RYNA di Ruxandra Zenide, Svizzera/Romania 2005 2 Circolo del cinema Locarno Cinema Morettina lun 2 febbraio, 20.30 COME HO VISSUTO LA FINE DEL MONDO Cum mi-am petrecut sfirsitul lumii di Catalin Mitulescu, Romania 2006 ven 6 febbraio, 20.30 4 MESI, 3 SETTIMANE E -

Critical Study on History of International Cinema

Critical Study on History of International Cinema *Dr. B. P. Mahesh Chandra Guru Professor, Department of Studies in Communication and Journalism, University of Mysore, Manasagangotri Karnataka India ** Dr.M.S.Sapna ***M.Prabhudevand **** Mr.M.Dileep Kumar India ABSTRACT The history of film began in the 1820s when the British Royal Society of Surgeons made pioneering efforts. In 1878 Edward Muybridge, an American photographer, did make a series of photographs of a running horse by using a series of cameras with glass plate film and fast exposure. By 1893, Thomas A. Edison‟s assistant, W.K.L.Dickson, developed a camera that made short 35mm films.In 1894, the Limiere brothers developed a device that not only took motion pictures but projected them as well in France. The first use of animation in movies was in 1899, with the production of the short film. The use of different camera speeds also appeared around 1900 in the films of Robert W. Paul and Hepworth.The technique of single frame animation was further developed in 1907 by Edwin S. Porter in the Teddy Bears. D.W. Griffith had the highest standing among American directors in the industry because of creative ventures. The years of the First World War were a complex transitional period for the film industry. By the 1920s, the United States had emerged as a prominent film making country. By the middle of the 19th century a variety of peephole toys and coin machines such as Zoetrope and Mutoscope appeared in arcade parlors throughout United States and Europe. By 1930, the film industry considerably improved its technical resources for reproducing sound. -

The Philadelphia Inquirer

The Philadelphia Inquirer September 10, 2009 “From Toronto to glory” The 34th International Film Festival, starting today, is where Oscar-eager flicks debut - among them, a searing doc about the Barnes Foundation. By Steven Rea Inquirer Movie Columnist and Critic Starting tonight with the world premiere of Creation, a movie about naturalist Charles Darwin starring Paul Bettany, and closing a week from Saturday with Young Victoria, with Emily Blunt as Britain's mighty monarch, the 34th Toronto International Film Festival promises 271 features and more than 500 filmmakers and red-carpet-treading stars. (Most of the 271 films are not about historic 19th-century Englishfolk.) An epic collision of studio releases with Oscar ambitions, of titles from Europe and Asia, Africa and the Americas, Down Under and Up There (Iceland, Scandinavia), TIFF09 boasts the latest from Pedro Almodóvar (Broken Embraces, with Penélope Cruz), the Coen brothers (A Serious Man), and documentarian Michael Moore (Capitalism: A Love Story). George Clooney will be there to talk up Up in the Air, and Megan Fox will pose provocatively as she unveils her hip horror exercise Jennifer's Body (scripted by Juno's Diablo Cody). Of particular interest to Philadelphia-area residents, and art lovers the world over, is Don Argott's The Art of the Steal, a conspiracy theory- documentary about the Barnes collection and its controversial move from Merion to a new site on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Although the film will have its world premiere Saturday at North America's biggest and most prestigious festival, The Art of the Steal was screened for a handful of critics in New York last week. -

Download (386.44KB)

Cronfa - Swansea University Open Access Repository _____________________________________________________________ This is an author produced version of a paper published in : The Routledge Companion to World Cinema Cronfa URL for this paper: http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa29914 _____________________________________________________________ Book chapter : Rydzewska, J. (2017). Developments in Eastern European Cinema since 1989. R. Stone, P. Cooke, S. Dennison, A. Marlow-Mann (Ed.), The Routledge Companion to World Cinema, Routledge. _____________________________________________________________ This article is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to publisher restrictions or conditions. When uploading content they are required to comply with their publisher agreement and the SHERPA RoMEO database to judge whether or not it is copyright safe to add this version of the paper to this repository. http://www.swansea.ac.uk/iss/researchsupport/cronfa-support/ Developments in Eastern European Cinemas since 1989 Elżbieta Ostrowska, University of Alberta Joanna Rydzewska, Swansea University ABSTRACT This chapter examines the ways in which Eastern European cinema has become Europeanized. It looks at how the idea of Eastern Europe and its cinema has been shaped vis-à-vis the West, and redefined after the collapse of communism. Contrary to the received wisdom that a new paradigm emerged in 1989, this chapter argues that it is only since 2000 that Eastern European cinema has enjoyed recognition after the near collapse of its film industries in the 1990s. In the three case studies of the Hungarian filmmaker Béla Tarr, Eastern European female directors and the Romanian New Wave, the chapter analyses the emergence in Eastern Europe of a new complex model of film production aligned with its larger European counterpart.