To Have and to Hold Catalog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

!=Il INTERNATIONAL S I WOMEN PILOTS

!= il INTERNATIONAL S i WOMEN PILOTS M a g a z i n ej OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE NINETY-NINES INC. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------January/February 2004 PERPETUAL CALENDAR 2004 MARCH JUNE 11-13 WAI Conference, NV. Visit The 99s 1 99 News Deadline - July/August Booth, www.wai.org. issue. Professional Pilot Leadership Initiative 13-17 Whirly Girls at HAI HeliExpo, Las Ve 23 application deadline. For further To list your 99s events gas, NV. Hovering on Sunday, March on this calendar page, 14. Contact: www.whirly-girls.org. or information, go to www.ninety- nines. org/careers/mentoring.htmI or send information to: HAI www.rotor.com. contact Laura Smith, PPLI Program The 99 News 18-20 Spring Board of Directors Meeting Leader, at mentoring@ninety- P.O. Box 950033 (travel days on March 17-21), Hilton nines.org. Oklahoma City, OK Garden Hotel, Oklahoma City, OK. 18-20 International Forest of Friendship, 73159 Meeting open to all who wish to at Atchison, KS. Em ail: tend. Contact Liz at Headquarters for more information, 405-685-7969. 25-27 Southern Wisconsin Airfest, Janesville articles99News(‘''cs.com Wisconsin. Contact: swairfest.org Online Form: 20 Northwest Section Winter Board M eeting, Kennewick Red Lion, JULY www.ninety-nines.org/ Kennewick, WA (across from the Co 6-11 2004 International Conference. 99newsreports.html lumBia Center Mall). Hotel pickup at Diamond Anniversary of The Ninety- Please indicate the Tri-Cities Airport in Pasco, WA. Busi Nines in Atlantic City, NJ. Sheraton name and location ness meeting 8 a.m. to noon. Special Atlantic City, hosted By the New York/ of the event, the activity planned for the afternoon at New Jersey Section. -

North Shore Sample

T a b l e o f C o n t e n t s Volume I Acknowledgments . iv Introduction . vii Maps of Long Island Estate Areas . xiv Factors Applicable to Usage . xvii Surname Entries A – M . 1 Volume II Surname Entries N – Z . 803 Appendices: ArcHitects . 1257 Civic Activists . 1299 Estate Names . 1317 Golf Courses on former NortH SHore Estates . 1351 Hereditary Titles . 1353 Landscape ArcHitects . 1355 Maiden Names . 1393 Motion Pictures Filmed at NortH SHore Estates . 1451 Occupations . 1457 ReHabilitative Secondary Uses of Surviving Estate Houses . 1499 Statesmen and Diplomats WHo Resided on Long Island's North Shore . 1505 Village Locations of Estates . 1517 America's First Age of Fortune: A Selected BibliograpHy . 1533 Selected BibliograpHic References to Individual NortH SHore Estate Owners . 1541 BiograpHical Sources Consulted . 1595 Maps Consulted for Estate Locations . 1597 PhotograpHic and Map Credits . 1598 I n t r o d u c t i o n Long Island's NortH SHore Gold Coast, more tHan any otHer section of tHe country, captured tHe imagination of twentieth-century America, even oversHadowing tHe Island's SoutH SHore and East End estate areas, wHich Have remained relatively unknown. THis, in part, is attributable to F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby, whicH continues to fascinate the public in its portrayal of the life-style, as Fitzgerald perceived it, of tHe NortH SHore elite of tHe 1920s.1 The NortH SHore estate era began in tHe latter part of the 1800s, more than forty years after many of the nation's wealtHy Had establisHed tHeir country Homes in tHe Towns of Babylon and Islip, along tHe Great SoutH Bay Ocean on tHe SoutH Shore of Long Island. -

Journal of the American Museum of Fly Fishing

The American Fly Fisher Journal of the American Museum of Fly Fishing WINTER 2006 VOLUME 32 NUMBER 1 A Storied Sport The Salmon, painted by T. C. Hofland, in T. C. Hofland, Esq., The British Angler’s Manual (London: H. B. Bond, 1848, 24). HE STORY OF FLY FISHING is the story of beautiful places, a Fly Fisherman: The Marvels of Wood,” Masseini profiles the story of the nice neighborhoods that trout and woodworker Giorgio Dallari, builder of pipes and wooden Tsalmon call home. It’s a materialistic story, both in the reels. Dallari’s pipes have a tiny salmon icon set in gold to con- sense of the physical tools we use to accomplish the task and nect pipe smoker with fly fisher. The idea to build wooden the types of access and accommodation money can buy. It’s a reels came to Dallari after he gave up other forms of fishing for spiritual story, as men and women search out the river, its chal- fly fishing. He has been building his reels since the mid-1980s. lenges, its rewards, and its peace. It’s the story of struggle With sumptuous photos, Masseini shares the work of Giorgio toward some things and struggle against others. It’s the story Dallari with us. This story begins on page 17. of a sport, with both its obvious outward goals and its more From the material beauty of wooden reels to the more inward, metaphoric ones. abstract beauty of the spiritual reach, we present “The Last This issue of the American Fly Fisher touches a bit on all of Religious House: A River Ran Through It” (page 14). -

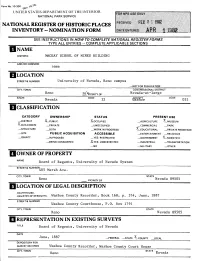

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 1 0-300 ^ UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ [NAME HISTORIC AND/OR COMMON same LOCATION STREET & NUMBER University of Nevada, Reno campus .NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Reno ICINITYOF Nevada-at-large STATE CODE .COUNTY CODE Nevada 32 wasnoe 031 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _D I STRICT X-PUBLIC X.OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE ^-MUSEUM ?_BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS ^-EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE _SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT X_SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED X.YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Board of Regents, University of Nevada System STREET & NUMBER 405 Marsh Ave. CITY, TOWN STATE Reno VICINITY OF Nevada 89505 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEos,ETC. Washoe County Recorder, Book 168, p. 374, June, 1887 STREET & NUMBER Washoe County Courthouse, P.O. Box 1791 CITY, TOWN STATE Reno Nevada 89505 1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Board of Regents, University of Nevada DATE June, 1887 —FEDERAL —STATE ^L-COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Washoe County Recorder, Washoe County Court House_____ CITY, TOWN Reno Nevada CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE GOOD —RUINS ^-ALTERED —MOVED DATE. —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Mackay School of Mines building is an educational, research and museum facility located in a detached setting at the north end of the University of Nevada, Reno campus main quadrangle. -

Discovering Mr. Cook Margaret A

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 2004 Discovering Mr. Cook Margaret A. Leary University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/1700 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the Legal Biography Commons, and the Legal Education Commons Recommended Citation Leary, Margaret A. "Discovering Mr. Cook." Law Quad. Notes 47, no. 2 (2004): 38-43. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Discovering Mr. Cook efore I begin to tell you some of what I've learned as I've tried to discover Mr. B[William W.] Cook, please ponder two questions: What are your feelings about the Law Quad buildings? Think, for example of the first time you entered the Quad; studying in the Reading Room; seeing the snowy Quad for the first time; and socializing in the Dining Room . You probably have a flood of memories connected to these buildings. Th following £ atur The Law School has outgrown them in many respects, but the buildings will always be i ba d on a talk giY n inspirational. to th La' hool' Second, let me ask what you know about William W. Cook? How did he acquire the Committe ofVi itor fortune he gave to the Law School? What law did he practice? Where, and when, did he la t fall. -

Meet the Bryant Concierge: a Team of Highly Ways to Make Your Patron Experience More Person- Al

MARCH / APRIL 2021 The Bryant Library, 2 Paper Mill Road, Roslyn, NY 11576 516-621-2240 • www.bryantlibrary.org To Our Valued Patrons, My hope is this message finds you and your fam- MEET ily safe and well. The Bryant Library continues to remain open providing materials and services to our patrons in the safest ways possible. Your safety and THE BRYANT the safety of our staff is our number one priority. As we continue to change and grow in this new CONCIERGE world of information gathering, we are also looking at Meet The Bryant Concierge: a team of highly ways to make your patron experience more person- al. With our additional reading clubs and concierge trained librarians ready to curate and collect services, The Bryant Library is increasing the way we personalized Library materials for your enjoy- connect with you as our patron. ment! Simply fill out the form on www.bryantli- brary.org and a Concierge will find the right I encourage you to watch for email blasts highlight- ing these services. Our newsletter contains infor- items for you. You will be called when your tote mation on so many wonderful programs available filled with personally selected books, movies, through our Zoom account. Programs for adults, and more are ready for pick up! teens, and children are available. We continue to offer curbside pickup and welcome you into the building for browsing. We are your one stop shop for connecting the community to valuable resources. MAKE A DIFFERENCE For those who are enjoying getting materials online, AT YOUR LIBRARY check out Hoopla, Kanopy, and our digital library. -

Brief Biographies of American Architects Who Died Between 1897 and 1947

Brief Biographies of American Architects Who Died Between 1897 and 1947 Transcribed from the American Art Annual by Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr., Director, Maine Historic Preservation Commission. Between 1897 and 1947 the American Art Annual and its successor volume Who's Who in American Art included brief obituaries of prominent American artists, sculptors, and architects. During this fifty-year period, the lives of more than twelve-hundred architects were summarized in anywhere from a few lines to several paragraphs. Recognizing the reference value of this information, I have carefully made verbatim transcriptions of these biographical notices, substituting full wording for abbreviations to provide for easier reading. After each entry, I have cited the volume in which the notice appeared and its date. The word "photo" after an architect's name indicates that a picture and copy negative of that individual is on file at the Maine Historic Preservation Commission. While the Art Annual and Who's Who contain few photographs of the architects, the Commission has gathered these from many sources and is pleased to make them available to researchers. The full text of these biographies are ordered alphabetically by surname: A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W Y Z For further information, please contact: Earle G. Shettleworth, Jr., Director Maine Historic Preservation Commission 55 Capitol Street, 65 State House Station Augusta, Maine 04333-0065 Telephone: 207/287-2132 FAX: 207/287-2335 E-Mail: [email protected] AMERICAN ARCHITECTS' BIOGRAPHIES: ABELL, W. -

Download File

FOUNDERS AND FUNDERS: Institutional Expansion and the Emergence of the American Cultural Capital 1840-1940 Valerie Paley Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2011 © 2011 Valerie Paley All rights reserved ABSTRACT Founders and Funders: Institutional Expansion and the Emergence of the American Cultural Capital 1840-1940 Valerie Paley The pattern of American institution building through private funding began in metropolises of all sizes soon after the nation’s founding. But by 1840, Manhattan’s geographical location and great natural harbor had made it America’s preeminent commercial and communications center and the undisputed capital of finance. Thus, as the largest and richest city in the United States, unsurprisingly, some of the most ambitious cultural institutions would rise there, and would lead the way in the creation of a distinctly American model of high culture. This dissertation describes New York City’s cultural transformation between 1840 and 1940, and focuses on three of its enduring monuments, the New York Public Library, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Metropolitan Opera. It seeks to demonstrate how trustees and financial supporters drove the foundational ideas, day-to-day operations, and self- conceptions of the organizations, even as their institutional agendas enhanced and galvanized the inherently boosterish spirit of the Empire City. Many board members were animated by the dual impulses of charity and obligation, and by their own lofty edifying ambitions for their philanthropies, their metropolis, and their country. Others also combined their cultural interests with more vain desires for social status. -

New World Records

New World Records NEW WORLD RECORDS 701 Seventh Avenue, New York, New York 10036; (212) 302-0460; (212) 944-1922 fax email: [email protected] www.newworldrecords.org The Vintage Irving Berlin New World NW 238 The eminent composer Jerome Kern once said, dreamed up some lyrics, and, with their resident “Irving Berlin has no place in American music. Nick Nicholson supplying the music,“Marie from He is American music.” Sunny Italy” was created. (Berlin received a royal- Apart from his music, Berlin symbolizes the ty of thirty-seven cents.) The number reached American dream of rags to riches. He was born print and made history for, because of a printer’s Israel Baline in Temun, a Jewish settlement in error, Baline was given credit as I. Berlin. He fan- Siberia, in 1888. His father, Moses, was a cantor cied “Berlin”but felt that “Izzy”was not sufficient- who, in order to escape the Cossack pogroms, ly high-toned, so he changed it to “Irving.” brought his wife, Leah, and his eight children to In 1911, Berlin wrote both the music (with the the United States, to a hand-to-mouth existence aid of a music secretary or arranger) and the on New York’s Lower East Side.Almost a century lyrics of “Alexander’s Ragtime Band.” Emma later, Israel Baline, now Irving Berlin, is a house- Carus, a vaudeville entertainer of the time, heard hold word and is married to the former Ellin it, liked it, and sang it. It caught hold. When Al Mackay, a prominent debutante of her day, with Jolson, an end man in a minstrel show, sang it, it three daughters and a bevy of grandchildren. -

Beaumont Facts & Trivia

BEAUMONT FACTS & TRIVIA CONTENTS. This Section covers interesting facts about the school, its old boys and some who were associated with Beaumont during its existence. Royal & Heads of State General Military League of Nations Politics & Diplomatic Countries worldwide Professions Sport ROYAL & HEADS OF STATE CONNECTIONS There were three official visits by Queen Victoria in 1882, 1887 and 1897 King Alfonso XIII of Spain 1906. King Carlos I of Portugal 1907 King Alfonso and Queen Ena (granddaughter of Queen Victoria) spent their honeymoon at Wardhouse - the Scottish estate of Major General Gordon OB. Prince Jaime Prince Alfonso with his wife Princess Beatrice Prince Jaime Duke of Madrid Carlist claimant to the Spanish throne and Legitimist pretender to the French throne was at Beaumont 1881-6. Prince Alfonso, Duke of Galliera, Infante of Spain was married to Princess Beatrice (of Saxe-Coburg & Gotha) granddaughter of Queen Victoria and Great Granddaughter of Tsar Alexander II Three other Spanish Royal Princes were at the school 1899 -1904 and Prince Jean de Borbon was at the school under the alias John Freeman 1914. Prince Sixte de Borbon-Parme Prince Michael Andreevich Prince Sixte de Borbon-Parme current Legitimist pretender to the French throne left the school in 1955. Prince Michael Andreevich of Russia, seen by many as the heir to the Tsar Nicholas II, was at the school when his family was given sanctuary at Frogmore by King George V. The last Hapsburg Emperor Blessed Charles and his family were rescued from Austria in 1919 by Colonel Edward Strutt OB known “as the Saviour of the Hapsburgs”. -

Jeanne Wier and the Nevada Historical Society, 1904-1950

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “We Seek to Be Patient”: Jeanne Wier and the Nevada Historical Society, 1904-1950 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Information Studies by Su Kim Chung 2015 © Copyright 2015 by Su Kim Chung ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “We Seek to Be Patient:” Jeanne Wier and the Nevada Historical Society, 1904-1950 by Su Kim Chung Doctor of Philosophy in Information Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Mary Niles Maack, Chair This dissertation focuses on Jeanne Wier and the years she was active in shaping the Nevada Historical Society (NHS), 1904-1950. It is the story of the institution as it unfolded over four decades, but more broadly, it considers how Wier shaped what Amanda Laugesen has framed as the idea of “public historical culture” in the state of Nevada. This culture not only included the collection of documents and books to provide a basis for research, but also the collection of relics for a museum that sought to be a showplace of Nevada’s history for her citizens. It includes the means by which the NHS performed outreach to make Nevada’s history a viable part of the community through anniversaries and celebrations and its efforts at preserving historic sites. The study considers the tension that arose in Wier’s attempts to have the NHS fulfill these different roles and the challenges that she faced in obtaining financial, governmental and community support for the institution. An important consideration of the ii dissertation is its evaluation of how successful Wier was in achieving the goals of the NHS regarding its mission of developing a historical consciousness within the state and its citizenry. -

Long Island Estates and Historical Photographs Collection, 1970-1980

Long Island Estates and Historical Photographs Collection, 1970-1980. Edith Hay Wyckoff, Collector. Special Collections Department/Long Island Studies Institute Contact Information: Special Collections Department Axinn Library, Room 032 123 Hofstra University Hempstead, NY 11549 Phone: (516) 463-6411, or 463-6404 Fax: (516) 463-6442 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.hofstra.edu/Libraries/SpecialCollections Compiled by: [P. Thompson] Date Completed: [August 8, 2012] Long Island Estates and Historical Photographs Collection, 1970-1980. Edith Hay Wyckoff, Collector. 1.5 cubic ft. Edith Hay Wyckoff (c.1917-2003) graduated from Great Neck H.S. in 1935. She resided in the historic Cock-Cornelius House in Locust Valley, N.Y., for over fifty years. Wyckoff was an author, journalist, and founder of the Locust Valley Leader, a newspaper at which she served as both editor and publisher. During her career, which spanned over half a century, she chronicled life on Long Island’s North Shore. The collection contains material that Wyckoff gathered during her career, including news clippings and photographs of Long Island estates such as Oheka Castle, Coe Hall, Falaise, Harbor Hill and Castle Gould. Also included are historical photographs of a variety of Long Island subjects, including historic buildings, ships, country clubs and hotels. Brief information about the estates that are included in this collection: Bayard Cutting Arboretum- William Bayard Cutting (1850-1912) The mansion was built in 1886 and designed by Charles C. Haight. The estate was given to the Long Island park commission in 1936 as a gift from Mrs. Bayard James, the daughter of William Bayard Cutting.