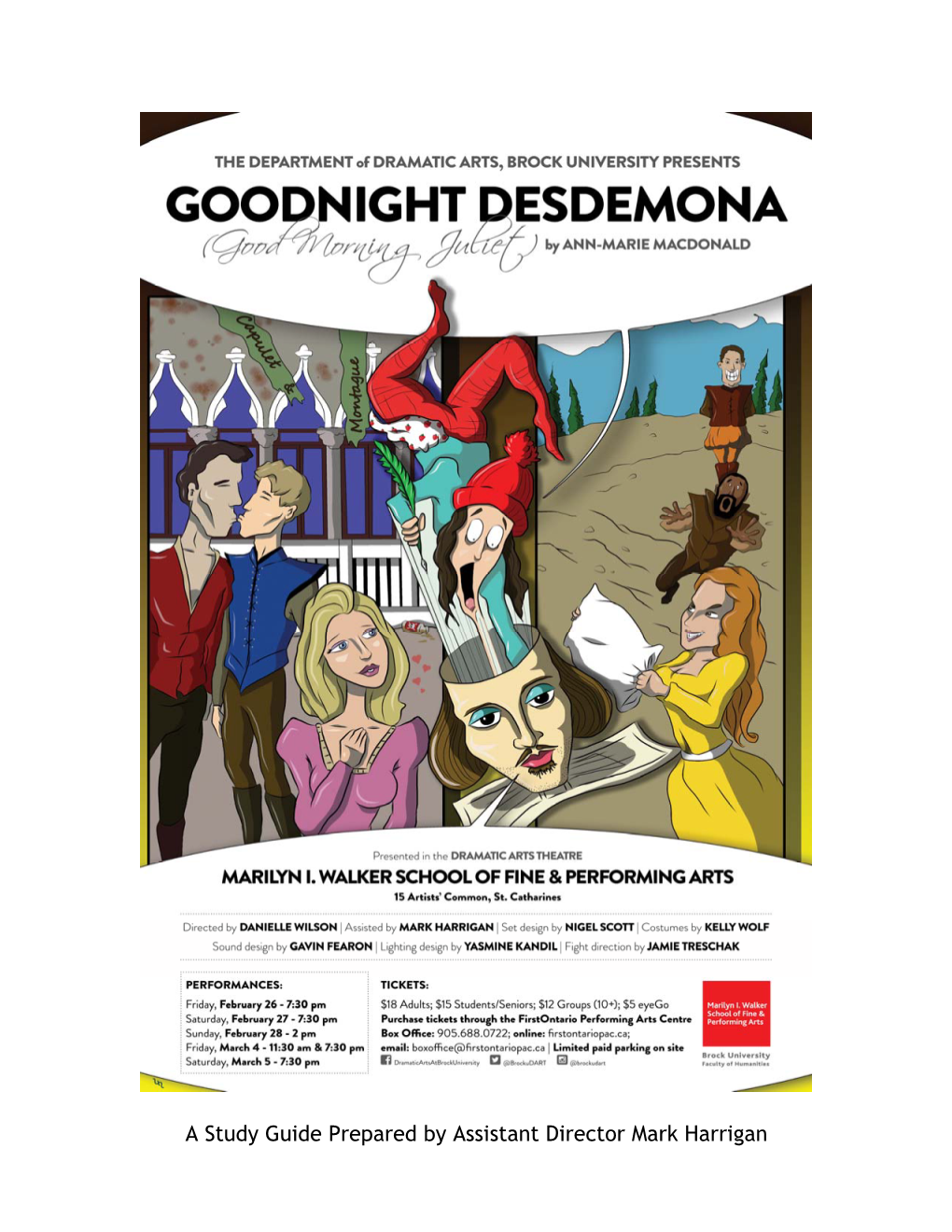

A Study Guide Prepared by Assistant Director Mark Harrigan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2018 Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations Rashmila Maiti University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Maiti, Rashmila, "Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 2905. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2905 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Mumbai Macbeth: Gender and Identity in Bollywood Adaptations A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies by Rashmila Maiti Jadavpur University Bachelor of Arts in English Literature, 2007 Jadavpur University Master of Arts in English Literature, 2009 August 2018 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. M. Keith Booker, PhD Dissertation Director Yajaira M. Padilla, PhD Frank Scheide, PhD Committee Member Committee Member Abstract This project analyzes adaptation in the Hindi film industry and how the concepts of gender and identity have changed from the original text to the contemporary adaptation. The original texts include religious epics, Shakespeare’s plays, Bengali novels which were written pre- independence, and Hollywood films. This venture uses adaptation theory as well as postmodernist and postcolonial theories to examine how women and men are represented in the adaptations as well as how contemporary audience expectations help to create the identity of the characters in the films. -

The Low-Status Character in Shakespeare's Comedies Linda St

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Masters Theses & Specialist Projects Graduate School 5-1-1973 The Low-Status Character in Shakespeare's Comedies Linda St. Clair Western Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation St. Clair, Linda, "The Low-Status Character in Shakespeare's Comedies" (1973). Masters Theses & Specialist Projects. Paper 1028. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/theses/1028 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses & Specialist Projects by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARCHIVES THE LOW-STATUS CHARACTER IN SHAKESPEAREf S CCiiEDIES A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of English Western Kentucky University Bov/ling Green, Kentucky In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Linda Abbott St. Clair May, 1973 THE LOW-STATUS CHARACTER IN SHAKESPEARE'S COMEDIES APPROVED >///!}<•/ -J?/ /f?3\ (Date) a D TfV OfThesis / A, ^ of the Grafduate School ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS With gratitude I express my appreciation to Dr. Addie Milliard who gave so generously of her time and knowledge to aid me in this study. My thanks also go to Dr. Nancy Davis and Dr. v.'ill Fridy, both of whom painstakingly read my first draft, offering invaluable suggestions for improvement. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii INTRODUCTION 1 THE EARLY COMEDIES 8 THE MIDDLE COMEDIES 35 THE LATER COMEDIES 8? CONCLUSION 106 BIBLIOGRAPHY Ill iv INTRODUCTION Just as the audience which viewed Shakespeare's plays was a diverse group made of all social classes, so are the characters which Shakespeare created. -

Cambridge Companion Shakespeare on Film

This page intentionally left blank Film adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays are increasingly popular and now figure prominently in the study of his work and its reception. This lively Companion is a collection of critical and historical essays on the films adapted from, and inspired by, Shakespeare’s plays. An international team of leading scholars discuss Shakespearean films from a variety of perspectives:as works of art in their own right; as products of the international movie industry; in terms of cinematic and theatrical genres; and as the work of particular directors from Laurence Olivier and Orson Welles to Franco Zeffirelli and Kenneth Branagh. They also consider specific issues such as the portrayal of Shakespeare’s women and the supernatural. The emphasis is on feature films for cinema, rather than television, with strong cov- erage of Hamlet, Richard III, Macbeth, King Lear and Romeo and Juliet. A guide to further reading and a useful filmography are also provided. Russell Jackson is Reader in Shakespeare Studies and Deputy Director of the Shakespeare Institute, University of Birmingham. He has worked as a textual adviser on several feature films including Shakespeare in Love and Kenneth Branagh’s Henry V, Much Ado About Nothing, Hamlet and Love’s Labour’s Lost. He is co-editor of Shakespeare: An Illustrated Stage History (1996) and two volumes in the Players of Shakespeare series. He has also edited Oscar Wilde’s plays. THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO SHAKESPEARE ON FILM CAMBRIDGE COMPANIONS TO LITERATURE The Cambridge Companion to Old English The Cambridge Companion to William Literature Faulkner edited by Malcolm Godden and Michael edited by Philip M. -

Othello and Its Rewritings, from Nineteenth-Century Burlesque to Post- Colonial Tragedy

Black Rams and Extravagant Strangers: Shakespeare’s Othello and its Rewritings, from Nineteenth-Century Burlesque to Post- Colonial Tragedy Catherine Ann Rosario Goldsmiths, University of London PhD thesis 1 Declaration I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own. 2 Acknowledgements Firstly, I want to thank my supervisor John London for his immense generosity, as it is through countless discussions with him that I have been able to crystallise and evolve my ideas. I should also like to thank my family who, as ever, have been so supportive, and my parents, in particular, for engaging with my research, and Ebi for being Ebi. Talking things over with my friends, and getting feedback, has also been very helpful. My particular thanks go to Lucy Jenks, Jay Luxembourg, Carrie Byrne, Corin Depper, Andrew Bryant, Emma Pask, Tony Crowley and Gareth Krisman, and to Rob Lapsley whose brilliant Theory evening classes first inspired me to return to academia. Lastly, I should like to thank all the assistance that I have had from Goldsmiths Library, the British Library, Senate House Library, the Birmingham Shakespeare Collection at Birmingham Central Library, Shakespeare’s Birthplace Trust and the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive. 3 Abstract The labyrinthine levels through which Othello moves, as Shakespeare draws on myriad theatrical forms in adapting a bald little tale, gives his characters a scintillating energy, a refusal to be domesticated in language. They remain as Derridian monsters, evading any enclosures, with the tragedy teetering perilously close to farce. Because of this fragility of identity, and Shakespeare’s radical decision to have a black tragic protagonist, Othello has attracted subsequent dramatists caught in their own identity struggles. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

(With) Shakespeare (/783437/Show) (Pdf) Elizabeth (/783437/Pdf) Klett

11/19/2019 Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation ISSN 1554-6985 V O L U M E X · N U M B E R 2 (/current) S P R I N G 2 0 1 7 (/previous) S h a k e s p e a r e a n d D a n c e E D I T E D B Y (/about) E l i z a b e t h K l e t t (/archive) C O N T E N T S Introduction: Dancing (With) Shakespeare (/783437/show) (pdf) Elizabeth (/783437/pdf) Klett "We'll measure them a measure, and be gone": Renaissance Dance Emily Practices and Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet (/783478/show) (pdf) Winerock (/783478/pdf) Creation Myths: Inspiration, Collaboration, and the Genesis of Amy Romeo and Juliet (/783458/show) (pdf) (/783458/pdf) Rodgers "A hall, a hall! Give room, and foot it, girls": Realizing the Dance Linda Scene in Romeo and Juliet on Film (/783440/show) (pdf) McJannet (/783440/pdf) Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet: Some Consequences of the “Happy Nona Ending” (/783442/show) (pdf) (/783442/pdf) Monahin Scotch Jig or Rope Dance? Choreographic Dramaturgy and Much Emma Ado About Nothing (/783439/show) (pdf) (/783439/pdf) Atwood A "Merry War": Synetic's Much Ado About Nothing and American Sheila T. Post-war Iconography (/783480/show) (pdf) (/783480/pdf) Cavanagh "Light your Cigarette with my Heart's Fire, My Love": Raunchy Madhavi Dances and a Golden-hearted Prostitute in Bhardwaj's Omkara Biswas (2006) (/783482/show) (pdf) (/783482/pdf) www.borrowers.uga.edu/7165/toc 1/2 11/19/2019 Borrowers and Lenders: The Journal of Shakespeare and Appropriation The Concord of This Discord: Adapting the Late Romances for Elizabeth the -

2019 Seminar Abstracts: the King's Men and Their Playwrights

1 2019 Seminar Abstracts: The King’s Men and Their Playwrights Meghan C. Andrews, Lycoming College James J. Marino, Cleveland State University “Astonishing Presence”: Writing for a Boy Actress of the King’s Men, c. 1610-1616 Roberta Barker, Dalhousie University Although scholarship has acknowledged the influence of leading actors such as Richard Burbage on the plays created for the King’s Men, less attention has been paid to the ways in which the gifts and limitations of individual boy actors may have affected the company’s playwrights. Thanks to the work of scholars such as David Kathman and Martin Wiggins, however, it is now more feasible than ever to identify the periods during which specific boys served their apprenticeships with the company and the plays in which they likely performed. Building on that scholarship, my paper will focus on the repertoire of Richard Robinson (c.1597-1648) during his reign as one of the King’s Men’s leading actors of female roles. Surviving evidence shows that Robinson played the Lady in Middleton’s Second Maiden’s Tragedy in 1611 and that he appeared in Jonson’s Catiline (1611) and Fletcher’s Bonduca (c.1612-14). Using a methodology first envisioned in 1699, when one of the interlocutors in James Wright’s Historia Histrionica dreamt of reconstructing the acting of pre-Civil War London by “gues[sing] at the action of the Men, by the Parts which we now read in the Old Plays” (3), I work from this evidence to suggest that Robinson excelled in the roles of nobly born, defiant tragic heroines: women of “astonishing presence,” as Helvetius says of the Lady in The Second Maiden’s Tragedy (2.1.74). -

The Comedies on Film1

The Comedies on Film1 MICHAEL HATTAWAY Compared with screen versions of the tragedies and histories, there have been few distinguished films based on the comedies. Max Reinhardt’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935) may be the only film in this genre to be acclaimed for its pioneering cinematography,2 and Franco Zeffirelli’s The Taming of the Shrew (1967), Kenneth Branagh’s Much Ado About Nothing (1993) 3, and Michael Radford’s The Merchant of Venice (2004) are the only three to have achieved popular (if not necessarily critical) success: the first for its use of actors (Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor) who were the co-supremes of their age, the second for cameo performances by photogenic stars, high spirits, and picturesque settings,4 and the third for fine cinematography and superb performances from Jeremy Irons and Al Pacino. Shakespeare’s comedies create relationships with their theatre audiences for which very few directors have managed to find cinematic equivalents, and it is not surprising that some of the comedies (The Comedy of Errors, The Merry Wives of Windsor, and The Two Gentlemen of Verona) have not been filmed in sound and in English for the cinema (although a couple have been the basis of adaptations). The problem plays or ‘dark comedies’ been have not been filmed for the cinema: presumably their sexual politics and toughness of analysis have never been thought likely to appeal to mass audiences, while The Taming of the Shrew, open as it is to both the idealisation and subjugation of women, has received a lot of attention, including versions from D.W. -

1 Orson Welles' Three Shakespeare Films: Macbeth, Othello, Chimes At

1 Orson Welles’ three Shakespeare films: Macbeth, Othello, Chimes at Midnight Macbeth To make any film, aware that there are plenty of people about who’d rather you weren’t doing so, and will be quite happy if you fail, must be a strain. To make films of Shakespeare plays under the same constraint requires a nature driven and thick-skinned above and beyond the normal, but it’s clear that Welles had it. His Macbeth was done cheaply in a studio in less than a month in 1948. His Othello was made over the years 1949-1952, on a variety of locations, and with huge gaps between shootings, as he sold himself as an actor to other film- makers so as to raise the money for the next sequence. I’m going to argue that the later movie shows evidence that he learned all kinds of lessons from the mistakes he made when shooting the first, and that there is a huge gain in quality as a consequence. Othello is a minor masterpiece: Macbeth is an almost unredeemed cock-up. We all know that the opening shot of Touch of Evil is a virtuoso piece of camerawork: a single unedited crane-shot lasting over three minutes. What is not often stressed is that there’s another continuous shot, less spectacular but no less well-crafted, in the middle of that film (it’s when the henchmen of Quinlan, the corrupt cop, plant evidence in the fall-guy’s hotel room). What is never mentioned is that there are two shots still longer in the middle of Macbeth . -

Merchant of Venice

Present In A SONY PICTURES CLASSICS RELEASE MOVISION ENTERTAINMENT and ARCLIGHT FILMS Association withUK FILM COUNCIL FILM FUND LUXEMBOURG, DELUX PRODUCTIONS S.A. IMMAGINE E CINEMA/DANIA FILM ISTITUTO LUCE A CARY BROKAW/AVENUE PICTURES NAVIDI-WILDE PRODUCTIONS JASON PIETTE – MICHAEL COWAN/SPICE FACTORY Production A MICHAEL RADFORD Film AL PACINO JEREMY IRONS JOSEPH FIENNES LYNN COLLINS WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE’S "THE MERCHANT OF VENICE" Supervising Make Up and ZULEIKHA ROBINSON KRIS MARSHALL CHARLIE COX HEATHER GOLDENHERSH MACKENZIE CROOK Art DirectorJON BUNKERHair Designer ANN BUCHANAN Costume Casting Music Film Production Director of DesignerSAMMY SHELDON DirectorSHARON HOWARD-FIELD byJOCELYN POOK EditorLUCIA ZUCCHETTI DesignerBRUNO RUBEO PhotographyBENOIT DELHOMME AFC Associate Co-Executive Co- Producer CLIVE WALDRON Producers GARY HAMILTON PETE MAGGI JULIA VERDIN Producers JIMMY DE BRABANT EDWIGE FENECH LUCIANO MARTINO ISTITUTO LUCE Co-Produced Executive by NIGEL GOLDSACK Producers MANFRED WILDE MICHAEL HAMMER PETER JAMES JAMES SIMPSON ALEX MARSHALL ROBERT JONES Produced Screenplay Directed Co- byCARY BROKAW BARRY NAVIDI JASON PIETTE MICHAEL LIONELLO COWAN byMICHAEL RADFORD byMICHAEL RADFORD A UK – LUXEMBOURG - ITALYProduction SOUNDTRACK AVAILABLE ON www.sonyclassics.com FOR SOME NUDITY. © 2004 SHYLOCK TRADING LIMITED, UK FILM COUNCIL, DELUX PRODUCTIONS S.A. AND IMMAGINE CINEMA S.R.L. Official Teacher’s Guide On DVD Spring 2005 Available on www.SonyStyle.com Check out “www.sonypictures.com/merchantofvenice” for more details TEACHER’S GUIDE By Mary E. Cregan, Ph.D Department of English, Barnard College NOTE TO TEACHERS The production of a major feature film of one of Shakespeare’s most controversial plays, The Merchant of Venice, provides literature teachers with an exciting opportunity to get students talking about some of the most difficult issues of our day—the tension between people of different cultures and religions—tensions that are as explosive today as they were in Shakespeare’s time. -

(Un)Doing Desdemona: Gender, Fetish, and Erotic Materialty in Othello

(UN)DOING DESDEMONA: GENDER, FETISH, AND EROTIC MATERIALTY IN OTHELLO A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English and American Literature By Perry D. Guevara, B.A. Washington, DC May 1, 2009 Dedicated to Cecilia (and Francisco, in memoriam) ii Acknowledgements (Un)Doing Desdemona: Gender, Fetish, and Erotic Materiality in Othello began as a suspicion—a mere twinkle of an idea—while reading Othello for Mimi Yiu's graduate seminar Shakespeare's Exotic Romances. I am indebted to Dr. Yiu for serving as my thesis advisor and for seeing this project through to its conclusion. I am also thankful to Ricardo Ortiz for serving on my oral exam committee and for ensuring that my ideas are carefully thought through. Thanks also to Lena Orlin, Dana Luciano, Patrick O'Malley, and M. Lindsay Kaplan for their continued instruction and encouragement. The feedback I received from Jonathan Goldberg (Emory University) and Mario DiGangi (City University University of New York—Graduate Center) proved particularly helpful during the final phases of writing. Furthermore, my thesis owes its life to my peers, not only for their generous feedback, but also for their invaluable friendship, especially Roya Biggie, Olga Tsyganova, Renata Marchione, Michael Ferrier, and Anna Kruse. Finally, I would like to thank my parents, Donna and Jess Guevara, for their unconditional love and support even though they think my work is “over their heads.” iii Table of Contents Introduction .........................................................................................................................1 Desdemona's Dildo............................................................................................................18 Coda ..................................................................................................................................68 iv I. -

Othello: a Teacher's Guide

A TEACHER’S GUIDE TO THE SIGNET CLASSIC EDITION OF WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE’S OTHELLO By DEBRA (DEE) JAMES, University of North Carolina at Asheville SERIES EDITORS: W. GEIGER ELLIS, ED.D., UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA, EMERITUS and ARTHEA J. S. REED, PH.D., UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, RETIRED A Teacher’s Guide to the Signet Classic Edition of William Shakespeare’s Othello 2 INTRODUCTION Othello, like all of Shakespeare’s plays, particularly the tragedies, is complex and subtly nuanced. Through its complexities and subtleties, Shakespeare makes us care about the characters who people this story. We understand their weaknesses and their strengths, their passions and their nobility. In our engagement in their lives and our pondering over what has gone wrong and why, we are given the opportunity to analyze human life both in the abstract and in the particular of our own lives. Shakespeare’s ability to involve us in the lives and fortunes of his characters is one of the best reasons for reading, rereading, and teaching Othello. Othello has particular gifts to offer to teenagers. It is a play about passion and reason. Intense feelings are exhibited here: love, hate, jealousy, envy, even lust. Teenagers struggling with their own passions can empathize with both Roderigo’s and Othello’s plight. It is also a play that examines, as do Shakespeare’s other works, human relationships and interactions. For teenagers in the first rush of attempting to understand how romantic relationships work and when and why they might fail, this text provides much to ponder. In addition, studying the play gives young people a rich literary vehicle for developing their critical thinking and analytical reading skills.