A Value Chain Analysis, Mvurwi, Zimbabwe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PLAAS RR46 Smeadzim 1.Pdf

Chrispen Sukume, Blasio Mavedzenge, Felix Murimbarima and Ian Scoones Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences Research Report 46 Space, Markets and Employment in Agricultural Development: Zimbabwe Country Report Chrispen Sukume, Blasio Mavedzenge, Felix Murimbarima and Ian Scoones Published by the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of the Western Cape, Private Bag X17, Bellville 7535, Cape Town, South Africa Tel: +27 21 959 3733 Fax: +27 21 959 3732 Email: [email protected] Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies Research Report no. 46 June 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher or the authors. Copy Editor: Vaun Cornell Series Editor: Rebecca Pointer Photographs: Pamela Ngwenya Typeset in Frutiger Thanks to the UK’s Department for International Development (DfID) and the Economic and Social Research Council’s (ESRC) Growth Research Programme Contents List of tables ................................................................................................................ ii List of figures .............................................................................................................. iii Acronyms and abbreviations ...................................................................................... v 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................ -

Fire Report 2014

ANNUAL FIRE REPORT 2014 FIRE Hay bailing along the Victoria Falls- Kazungula Road to reduce road side fires Page 1 of 24 ANNUAL FIRE REPORT 2014 Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 3 2.0 Fire Prediction Modelling ..................................................................................................................... 3 3.0 Fire Monitoring .................................................................................................................................... 7 4.0 Environmental Education and Training ................................................................................................ 8 5.0 EMA/ZRP Fire Management Awards ................................................................................................. 14 6.0 Law enforcement ............................................................................................................................... 17 7.0 Impacts of Fires .................................................................................................................................. 18 7.0 Conclusion .......................................................................................................................................... 21 8.0 Recommendations ............................................................................................................................. 22 Annex 1: Pictures .................................................................................................................................... -

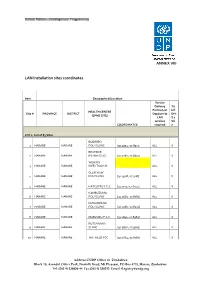

LAN Installation Sites Coordinates

ANNEX VIII LAN Installation sites coordinates Item Geographical/Location Service Delivery Tic Points (List k if HEALTH CENTRE Site # PROVINCE DISTRICT Dept/umits DHI (EPMS SITE) LAN S 2 services Sit COORDINATES required e LOT 1: List of 83 Sites BUDIRIRO 1 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9354,-17.8912] ALL X BEATRICE 2 HARARE HARARE RD.INFECTIO [31.0282,-17.8601] ALL X WILKINS 3 HARARE HARARE INFECTIOUS H ALL X GLEN VIEW 4 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9508,-17.908] ALL X 5 HARARE HARARE HATCLIFFE P.C.C. [31.1075,-17.6974] ALL X KAMBUZUMA 6 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9683,-17.8581] ALL X KUWADZANA 7 HARARE HARARE POLYCLINIC [30.9285,-17.8323] ALL X 8 HARARE HARARE MABVUKU P.C.C. [31.1841,-17.8389] ALL X RUTSANANA 9 HARARE HARARE CLINIC [30.9861,-17.9065] ALL X 10 HARARE HARARE HATFIELD PCC [31.0864,-17.8787] ALL X Address UNDP Office in Zimbabwe Block 10, Arundel Office Park, Norfolk Road, Mt Pleasant, PO Box 4775, Harare, Zimbabwe Tel: (263 4) 338836-44 Fax:(263 4) 338292 Email: [email protected] NEWLANDS 11 HARARE HARARE CLINIC ALL X SEKE SOUTH 12 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA CLINIC [31.0763,-18.0314] ALL X SEKE NORTH 13 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA CLINIC [31.0943,-18.0152] ALL X 14 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA ST.MARYS CLINIC [31.0427,-17.9947] ALL X 15 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA ZENGEZA CLINIC [31.0582,-18.0066] ALL X CHITUNGWIZA CENTRAL 16 HARARE CHITUNGWIZA HOSPITAL [31.0628,-18.0176] ALL X HARARE CENTRAL 17 HARARE HARARE HOSPITAL [31.0128,-17.8609] ALL X PARIRENYATWA CENTRAL 18 HARARE HARARE HOSPITAL [30.0433,-17.8122] ALL X MURAMBINDA [31.65555953980,- 19 MANICALAND -

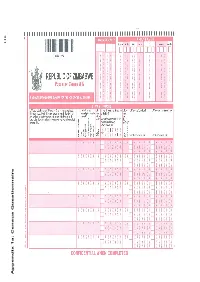

Government Gazette

ZIMBABWEAN, GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Published by Authority f Vol. LX, No. 33 I4th MAY, 1982 Price 30c General Notice 443 of1982. “ts RESERVE BANK OF ZIMBABWE ACT [CHAPTER 173}. Statement of Assets and Liabilities of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe :5 . ey = IN termsofsection 20 of the Réserve Bank of Zimbabwe Act [Chapter 173], a statementofthe assets andliabilities of the Reserve Bank of Zimbabweas at the 30th April, 1982, is published in the Schedule. ' 14-5-82. B. WALTERS, : me ‘ - Secretaryto the ‘Treasury. oo SCHEDULE *s , | oS STATEMENT OF ASSETS AND LIABILITIES AS AT THE 307ra APRIL, 1982 Liabilities . Assets> : Capital ee ee _ 2000 000 Gold and foreign assets : General 156 429 939 Reserve Fund... jr5-200 000 ° Loans and advances , 42 105 000 Currency in circulation. 2 . 2... 39 389 892 Tnternal investments— . core o e 4 6 ) 276.227 845 Deposits and other liabilities to the public . 9 012 Governmentstock . Other . 110342 535 liabilities ee eee 112 230 527 | Other. 165 885 310 \ Other assets °° 164 606 647 $639 369 431 $639 369 431 . , General Notice 444of 1982. LIQUOR ACT [CHAPTER 289] Liquor Licensing Board: Annual Meeting: Mtoko District PURSUANT to the'provisions of subsection (1) of section 47 of the Liquor Act [Chapter 289), notice is hereby given that the annual meeting of the Liquor Licensing Board for the district of Mtoko will be held at the Administrative Court, Chaplin Buildings, Samora Machel Avenue Central, Harare, commencing at 9 a.m. on Monday the 7th day of June, 1982, to consider the following matters: . y ; APPLICATIONS FOR NEW LIQUOR LICENCES, ; ® ~ BOTTLE LIQUOR LICENCES Trading name Situation ofpremises Applicant Proposedmanager Gurupjra General Dealer and Bottle Lease site T.T. -

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE - Basemap

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE - Basemap Mashonaland Central Karanda Chimandau Guruve MukosaMukosa Guruve Kamusasa Karanda Marymount Matsvitsi Marymount Mary Mount Locations ShinjeShinje Horseshoe Nyamahobobo Ruyamuro RUSHINGA CentenaryDavid Nelson Nyamatikiti Nyamatikiti Province Capital Nyakapupu M a z o w e CENTENARY Mazowe St. Pius MOUNT DARWIN 2 Chipuriro Mount DarwinZRP NyanzouNyanzou Mt Darwin Chidikamwedzi Town 17 GoromonziNyahuku Tsakare GURUVE Jingamvura MAKONDE Kafura Nyamhondoro Place of Local Importance Bepura 40 Kafura Mugarakamwe Mudindo Nyamanyora Chingamuka Bure Katanya Nyamanyora Bare Chihuri Dindi ARDA Sisi Manga Dindi Goora Mission M u s e n g e z i Nyakasoro KondoKondo Zvomanyanga Goora Wa l t o n Chinehasha Madziwa Chitsungo Mine Silverside Donje Madombwe Mutepatepa Nyamaruro C o w l e y Chistungo Chisvo DenderaDendera Nyamapanda Birkdale Chimukoko Nyamapanda Chindunduma 13 Mukodzongi UMFURUDZI SAFARI AREA Madziwa Chiunye KotwaKotwa 16 Chiunye Shinga Health Facility Nyakudya UZUMBA MARAMBA PFUNGWE Shinga Kotwa Nyakudya Bradley Institute Borera Kapotesa Shopo ChakondaTakawira MvurwiMvurwi Makope Raffingora Jester H y d e Maramba Ayrshire Madziwa Raffingora Mvurwi Farm Health Scheme Nyamaropa MUDZI Kasimbwi Masarakufa Boundaries Rusununguko Madziva Mine Madziwa Vanad R u y a Madziwa Masarakufa Shutu Nyamukoho P e m b i Nzvimbo M u f u r u d z i Madziva Teacher's College Vanad Nzvimbo Chidembo SHAMVA Masenda National Boundary Feock MutawatawaMutawatawa Mudzi Rosa Muswewenhede Chakonda Suswe Mutorashanga Madimutsa Chiwarira -

Census Results in Brief

116 Appendix 1a: Census Questionnaire 117 118 119 120 Appendix 1b: Census Questionnaire Code List Question 6-8 and 10 Census District Country code MANICALAND 1 Sanyati 407 Shurugwi 726 Rural Districts Urban Areas MASVINGO 8 Buhera 101 Chinhoyi 421 Rural Districts Chimanimani 102 Kadoma 422 Bikita 801 Chipinge 103 Chegutu 423 Chiredzi 802 Makoni 104 Kariba 424 Chivi 803 Mutare Rural 105 Norton 425 Gutu 804 Mutasa 106 Karoi 426 Masvingo Rural 805 Nyanga 107 MATABELELAND NORTH 5 Mwenezi 806 Urban Areas Rural Districts Zaka 807 Mutare 121 Binga 501 Urban Areas Rusape 122 Bubi 502 Masvingo Urban 821 Chipinge 123 Hwange 503 Chiredzi Town 822 MASHONALAND CENTRAL 2 Lupane 504 Rural Districts Nkayi 505 HARARE 9 Bindura 201 Tsholotsho 506 Harare Rural 901 Centenary 202 Umguza 507 Harare Urban 921 Guruve 203 Urban Areas Chitungwiza 922 Mazowe 204 Hwange 521 Epworth 923 Mount Darwin 205 Victoria Falls 522 BULAWAYO 0 Rushinga 206 MATABELELAND SOUTH 6 Bulawayo Urban 21 Shamva 207 Rural Districts AFRICAN COUNTRIES Mbire 208 Beitbridge Rural 601 Zimbabwe 0 Urban Areas Bulilima 602 Botswana 941 Bindura 221 Mangwe 603 Malawi 942 Mvurwi 222 Gwanda Rural 604 Mozambique 943 MASHONALAND EAST 3 Insiza 605 South Africa 944 Rural Districts Matobo 606 Zambia 945 Chikomba 301 Umzingwane 607 Other African Countries 949 Goromonzi 302 Urban Areas OUTSIDE AFRICA Hwedza 303 Gwanda 621 United Kingdom 951 Marondera 304 Beitbridge Urban 622 Other European Countries 952 Mudzi 305 Plumtree 623 American Countries 953 Murehwa 306 MIDLANDS 7 Asian Countries 954 Mutoko 307 Rural Districts Other Countries 959 701 Seke 308 Chirumhanzu Uzumba-Maramba-Pfungwe 309 Gokwe North 702 Urban Areas Gokwe South 703 Marondera 321 Gweru Rural 704 Chivhu Town Board 322 Kwekwe Rural 705 Ruwa Local Board 323 Mberengwa 706 MASHONALAND WEST 4 Shurugwi 707 Rural Districts Zvishavane 708 Chegutu 401 Urban Areas Hurungwe 402 Gweru 721 Mhondoro-Ngezi 403 Kwekwe 722 Kariba 404 Redcliff 723 Makonde 405 Zvishavane 724 Gokwe Centre 725 . -

The Political Economy of Civilisation: Peasant-Workers in Zimbabwe and the Neo-Colonial World

The Political Economy of Civilisation: Peasant-Workers in Zimbabwe and the Neo-colonial World Paris Yeros Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Relations, London School of Economics and Political Science, University of London UMI Number: U172056 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U172056 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 TW£&£ S S097 ABSTRACT This thesis provides a global political economy of the postwar period, with special reference to Zimbabwe. The conceptual aim is to connect the agrarian question with contemporary democratic theory, by inquiring into the global sources of ‘civil society’ and relating it to the phenomenon of semi-proletarianisation. There are three basic arguments. First, civil society cannot be understood in isolation from imperialism. The onset of the Cold War produced an ultra-imperial order under US leadership, with a ‘global development’ project crafted to its needs and a mode of rule preoccupied with the definition and enforcement of ‘civil society’. Second, capital accumulation in the postwar period has continued to operate in accordance with the laws of motion of the centre-periphery relationship; the main alteration has consisted in the closer integration of central-state economies with each other, along with a small number of industrial satellites. -

Zimbabwe Humanitarian Situation Report

Zimbabwe Humanitarian Situation Report Multihazard Situation Report # 9: January-December 2019 Situation in Numbers Highlights 3,700,000 According to the ZIMVAC (2019) assessments in both rural and urban children in need of humanitarian areas, a total of 7.7 million people (including 3.7 million children) were assistance in rural and urban areas in urgent need of humanitarian assistance in 2019.1 (ZimVAC, July &September Cyclone Idai made landfall on 15 March 2019, affecting 270,000 2019) people (including 129,900 children) mostly in Chimanimani and Chipinge districts. With an annual inflation of 481 per cent projected in November 2019, 7,700,000 most households are unable to afford basic foods (mealie meal and people in need in rural and bread) and services including healthcare, water and sanitation and urban areas education. (ZimVAC, July &September 17,763 cases of severe acute malnutrition were treated in 2019 and 2019) over 1,500 cases of pellagra (vitamin B3 deficiency) were reported since January, exposing major nutritional challenges in the country. Over 1.3 million people accessed safe drinking water in 2019 through 270,000 people distribution of water treatment materials and rehabilitation of Affected by the residual impact boreholes, springs and piped water schemes. of flooding At least 75,000 vulnerable children were provided with critical child (UNOCHA, March 2019) protection services, including 920 unaccompanied children. 129,600 children Affected by flooding (UNICEF, April 2019) UNICEF Appeal 2019 US$ 23.7 million -

Covid-19 Addendum

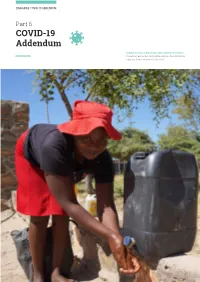

ZIMBABWE COVID-19 ADDENDUM Part 6 COVID-19 Addendum SHAMVA DISTRICT, MASHONALAND CENTRAL PROVINCE A beneficiary washes her hands before entering a food distribution in Shamva district. Photo:WFP/Claire Nevill 46 ZIMBABWE COVID-19 ADDENDUM COVID-19 Response at a Glance PEOPLE IN NEED PEOPLE TARGETED REQUIREMENTS (US$) OPERATIONAL PARTNERS 7.5M 5.9M $84.9M 37 People in Need and Targeted Requirements by Cluster H M Me Hurungwe Cy/ Mabani M F S M U Dwin Rushinga MASHONALAND CENTRAL Karoi M Guruve Mwi M Shamva M AIBA Kariba Zvimba B Pfungwe Cyi U M Mowe MASHONALAND EAST Education Ba Moko Nth MASHONALAND WEST Nton Goromonzi HARARE Mehwa B South Sanyati C Water S U Nanga V Monder M Kadoma M Town Seke U U C H WASH U MIDLANDS Mondera MANICALAND M-N Hdweza Rusape M Lupane Kwekwe MATEBELELAND NORTH K Nyi C N U M Hwange Redcliff M U C Ba urban Gutu Me Tsholotsho B Gweru U U P BV Byo C M MASVINGO I B C M Zvishavane U B Zvishavane U Z U U M C Potection Plumtree Mengwa MATEBELELAND SOUTH 2M C C Potection U U M Mobo M Gwanda Cedzi B SM M Propor IN Targeted B P geted U R 02M People in Need and Targeted by Cluster Operational Partners by Type Water S M H WASH 2M F S 0M M NNO Education M 9 M INO H M 18 0M PBV 2M 845K PP 22M UN 22 0 MS 20M 20 0M N 353K 2 S 91K In addition to the humanitarian response requirements, R 14K $4.5 million is needed to support Governance interventions 14K dination and $22.5 million for social protection, which will be 953 M 953 carried out by development actors. -

National Rapid Response Team Contacts

National Rapid Response Team Contacts City/Town Contact Person Mobile Number Toll free Number Institution/Role Ace Ambulance +263 782999901-4 (0) 8080412 Harare ZRP (0242) 777777 ZRP Harare - Wilkins (0242) 741872 Wilkins Hosp Harare - Wilkins (0242) 740404 Wilkins Hosp Harare Dr Chonzi +263 712860777 Harare Dr Bara +263 734322293 Harare Dr Mudariki +263 772974314 Bulawayo Ms Sibanda +263 772677476 Bulawayo Dr Nyathi +263 776248128 Bulawayo Dr Ncube +263 772424812 Bulawayo Dr E Sibanda +263 772880581 Director Health Services Bulilima Dr Hapanyengwi +263 772907621 Beitbridge Dr Samhere +263 772386895 Bindura Mr Karisa +263 773271670 DMO Bikita Dr Mungwari +263 715411650 Centenary/Muzarabani Mr Kangundu +263 777366045 DNO Chegutu Dr Masvosva +263 772720190 Chiredzi Dr Dhlandhlara +263 775094360 Chirumanzu Dr S Maunga +263 772286685 (0) 8080435 Chirumanzu Mr Mukomberanwa +263 773 394 154 (0) 8080435 Chirumanzu Sr Mutumwa +263 772 911 454 (0) 8080435 Concession Dr Sosera +263 774736753 Gokwe North DR Chikara +263 775 428800 Gokwe North E Muchenje +263772 575437 City/Town Contact Person Mobile Number Toll free Number Institution/Role Gokwe South DR Mashoko +263 774 074739 Gokwe South D Mukotsi +263 774 002 934 Goromonzi Dr Karim +263 772347378 Guruve Zvomuya +263 772641444 DNO Gwanda Dr Gwarimbo +263 775735679 Gweru Dr Mhene +263 773258210 (0) 8080435 Gweru Provincial Hosp Toll free +263 787822276 (0) 8080435 Gweru Provincial Hospital Gweru& City G Shariwa +263 773 639 797 (0) 8080435 Gweru& City Mr Sekanhamo +263 715017014 (0) 8080435 Gweru& -

Lions Clubs International Club Membership Register the Clubs and Membership Figures Reflect Changes As of March 2005

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF MARCH 2005 CLUB MMR MMR FCL YR MEMBERSHI P CHANGES TOTAL TYPE IDENT NBR CLUB NAME DIST RPT DATE RCV DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 7300 027882 BANKET-TRELAWNEY 412 8 0 0 0 0 0 8 7300 027883 BEIT BRIDGE 412 1 10-2004 10-14-2004 -4 -4 4 0 0 0 -4 -4 0 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 07-2004 08-18-2004 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 08-2004 08-18-2004 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 08-2004 08-18-2004 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 09-2004 09-17-2004 1 1 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 09-2004 10-01-2004 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 10-2004 10-01-2004 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 11-2004 11-26-2004 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 12-2004 12-06-2004 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 01-2005 01-14-2005 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 02-2005 02-05-2005 7300 027886 BULAWAYO 412 1 03-2005 03-01-2005 21 0 1 0 0 1 22 7300 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS 412 1 06-2004 03-01-2005 2 -5 -3 7300 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS 412 1 07-2004 03-01-2005 7300 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS 412 1 08-2004 03-01-2005 7300 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS 412 1 09-2004 03-01-2005 7300 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS 412 1 10-2004 03-01-2005 7300 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS 412 1 11-2004 03-01-2005 7300 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS 412 1 12-2004 03-01-2005 -2 -2 7300 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS 412 1 01-2005 03-01-2005 7300 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS 412 1 02-2005 03-01-2005 7300 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS 412 1 03-2005 03-22-2005 20 2 0 0 -7 -5 15 7300 027889 CHIREDZI 412 1 05-2004 08-18-2004 7300 027889 CHIREDZI 412 1 06-2004 08-18-2004 7300 -

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE - Overview Map 26 October 2009 Legend Province Capital

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE - Overview Map 26 October 2009 Legend Province Capital Hunyani Casembi Key Location Chikafa Chidodo Muzeza Musengezi Mine Mushumbi Musengezi Pools Chadereka Mission Mbire Mukumbura Place of Local Importance Hoya Kaitano Kamutsenzere Kamuchikukundu Bwazi Muzarabani Mavhuradonha Village Bakasa St. St. Gunganyama Pachanza Centenary Alberts Alberts Nembire Road Network Kazunga Chawarura Dotito Primary Chironga Rushinga Mount Rushinga Mukosa Guruve Karanda Rusambo Marymount Chimanda Secondary Marymount Shinje Darwin Rusambo Centenary Nyamatikiti Guruve Feeder azowe MashonalandMount M River Goromonzi Darwin Mudindo Dindi Kafura Bure Nyamanyora Railway Line Central Goora Kondo Madombwe Chistungo Mutepatepa Dendera Nyamapanda International Boundary Madziwa Borera Chiunye Kotwa Nyakudya Shinga Bradley Jester Mvurwi Madziwa Vanad Kasimbwi Institute Masarakufa Nzvimbo Madziwa Province Boundary Feock Mutawatawa Mudzi Muswewenhede Chakonda Suswe Mudzi Mutorashanga Charewa Chikwizo Howard District Boundary Nyota Shamva Nyamatawa Gozi Institute Bindura Chindengu Kawere Muriel Katiyo Rwenya Freda & Mont Dor Caesar Nyamuzuwe River Mazowe Rebecca Uzumba Nyamuzuwe Katsande Makaha River Shamva Mudzonga Makosa Trojan Shamva Nyamakope Fambe Glendale BINDURA MarambaKarimbika Sutton Amandas Uzumba All Nakiwa Kapondoro Concession Manhenga Kanyongo Souls Great Muonwe Mutoko PfungweMuswe Dyke Mushimbo Chimsasa Lake/Waterbody Madamombe Jumbo Bosha Nyadiri Avila Makumbe Mutoko Jumbo Mazowe Makumbe Parirewa Nyawa Rutope Conservation Area