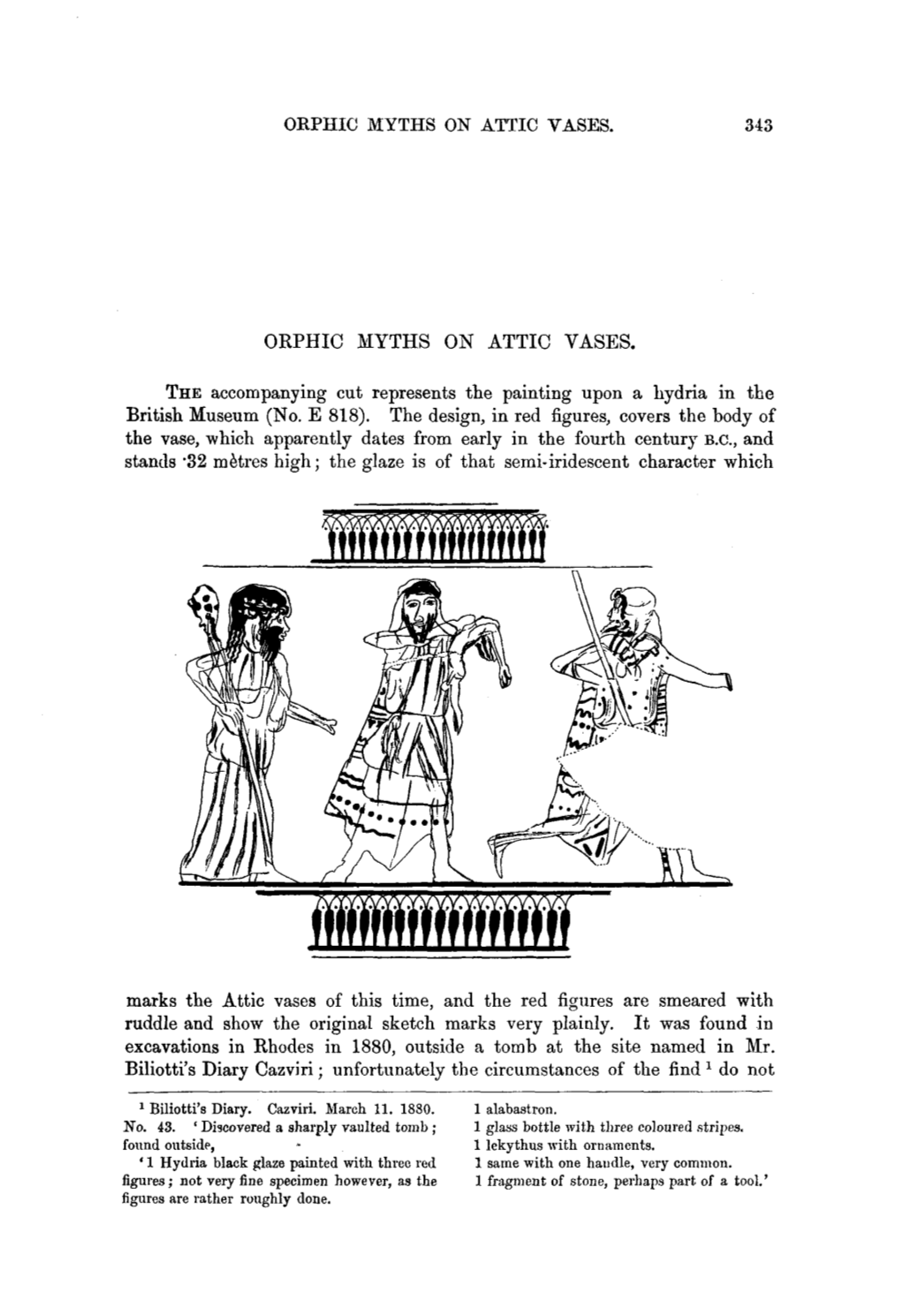

Orphic Myths on Attic Vases. Orphic Myths On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Titanic Origin of Humans: the Melian Nymphs and Zagreus Velvet Yates

The Titanic Origin of Humans: The Melian Nymphs and Zagreus Velvet Yates HE FIRST PART of this paper examines a minor mystery in Hesiod’s Theogony, centering around the Melian Nymphs, Tin order to assess the suggestions, both ancient and modern, that the Melian Nymphs were the mothers of the human race. The second part examines the afterlife of Hesiod’s Melian Nymphs over a thousand years later, in the allegorizing myths of late Neoplatonism, in order to suggest that the Hesiodic myth in which the Melian Nymphs primarily figure, namely the castration of Ouranos, has close similarities to a central Neoplatonic myth, that of Zagreus. Both myths depict a “Titanic” act of destruction and separation which leads to the birth of the human race. Both myths furthermore seek to account for a divine element which human nature retains from its origins. The Melian Nymphs in Hesiod ˜ssai går =ayãmiggew ép°ssuyen aflmatÒessai, pãsaw d°jato Ga›a: periplom°nou d' §niautoË ge¤nat' ÉErinËw te krateråw megãlouw te G¤gantaw, teÊxesi lampom°nouw, dol¤x' ¶gxea xers‹n ¶xontaw, NÊmfaw y' ìw Mel¤aw kal°ous' §p' épe¤rona ga›an. Gaia took in all the bloody drops that spattered off, and as the seasons of the year turned round she bore the potent Furies and the Giants, immense, dazzling in their armor, holding long spears in their hands, and then she bore the Melian Nymphs on the boundless earth.1 1 Theog. 183–187. Translations of Hesiod adapted from A. Athanassakis, Hesiod: Theogony, Works and Days, Shield (Baltimore 1983). -

Persephone: Symbol of Rebirth

SECTION II CHAPTER 7 PERSEPHONE: SYMBOL OF REBIRTH PAPER CONTENTS INTRODUCTION MYTHIC TALE: SYNOPSIS LORD HADES: ARCHETYPE OF THE DEATH FORCE DEMETER: ARCHETYPE OF THE LIFE FORCE THE UNDERWORLD: WORLD OF SHADOWS AND SOULS PERSEPHONE: THE WAY OF THE FEMININE Name and Origins Daughterhood Abduction and Marriage Pomegranate Judgment of Seasons Motherhood Queenhood Deep Feminine Caretaker of Souls RETURN AND REBIRTH FEMININE INDIVIDUATION CLOSING COMENTS 1 INTRODUCTION The mythic tale of Persephone’s abduction by Hades, the personification of the Death Force, and the unremitting search by her mother, Demeter, Goddess exemplar of the Life Force, relates a fascinating account of how Death and Life Forces interact with each other. In the tale, Persephone holds the tension between Life and Death Forces and in doing so produces a new alterative, Rebirth. As maiden she is ever ready to birth, to give Life. Although Persephone's name means 'Bringer of Destruction', as Queen of the Underworld she regenerates the Souls that come to her realm. The mythic tale suggests that the resolution of the tension between Life and Death leads to the transcendent third. The prior two chapters focus on transformation that is needed for the feminine to carry out the “return” from its suppressed state. The chapter on Pele and Hi’iaka brought attention to feminine transformation that occurred when relationship based on fertility gave way to relationship based on personal encounter. The chapter on The Goose Girl addresses the transformation that leads to feminine personhood when daughter separates from the mother. In this chapter attention is given to the transformation that rebirth brings about, namely, enabling and revitalizing the Individuation Process. -

Hades: a Myth-Critical Approach

HADES: A MYTH-CRITICAL APPROACH SUPERGIANT GAMES: Hades (Nintendo Switch version). [digital game]. San Francisco, CA : Supergiant games, 2020. Andrea Quero “Imagine that Prince Zagreus experiences some sort of joyous outcome, for a change, in contrast to the arbitrary and unfortunately painful death he shall experience... now.” The Narrator Hades is a roguelike indie game published by Supergiant Games on September 17, 2020, for both PC and the Nintendo Switch. This game follows Zagreus – son of Ha- des – through his attempt to escape from the Underworld. A tale as old as time: men vs fate. The Greek understood destiny as an inescapable lifepath woven by the Moirae for each child prior to or just after their birth.1 Such a vision implied that nobody could ever change fate, no matter how hard they tried. It is worth noting that the game’s core mechanics are intertwined with the narrative that is presented to the player, displaying fulfilling character development through the lens of a genre that fits its narrative like a glove. The gameplay reflects the seemingly endless struggle of fighting against fate: the player must go through the same biomes – the Tartarus, Asphodel, Elysium, and the Temple of Styx – over and over, to help Zagreus overcoming his destiny of staying in the Underworld for eternity. All things considered, it is no coincidence that Zagreus and Sisyphus meet in the Underworld, since their stories mirror each other. There is a mutually reinforcing rela- tionship between the old myth about the man forced to roll a giant boulder up a hill only for it to fall every time, and Zagreus mythical retelling of the son of Hades failing to run away from the Underworld. -

Greek Mythology Gods and Goddesses

Greek Mythology Gods and Goddesses Uranus Gaia Cronos Rhea Hestia Demeter Hera Hades Poseidon Zeus Athena Ares Hephaestus Aphrodite Apollo Artemis Hermes Dionysus Book List: 1. Homer’s the Iliad and the Odyssey - Several abridged versions available 2. Percy Jackson’s Greek Gods by Rick Riordan 3. Percy Jackson and the Olympians series by, Rick Riordan 4. Treasury of Greek Mythology by, Donna Jo Napoli 5. Olympians Graphic Novel series by, George O’Connor 6. Antigoddess series by, Kendare Blake Website References: https://www.greekmythology.com/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Family_tree_of_the_Greek_gods https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-history/greek-mythology King of the Gods God of the Sky, Thunder, Lightning, Order, Law, Justice Married to: Hera (and various consorts) Symbols: Thunderbolt, Eagle, Oak, Bull Children: MANY, including; Aphrodite, Apollo, Ares, Artemis, Athena, Dionysus, Hermes, Persephone, Hercules, Helen of Troy, Perseus and the Muses Interesting Story: When father, Cronos, swallowed all of Zeus’ siblings (Hestia, Demeter, Hera, Hades and Poseidon) Zeus was the one who killed Cronos and rescued them. Roman Name: Jupiter God of the Sea Storms, Earthquakes, Horses Married to: Amphitrite (various consorts) Symbols: Trident, Fish, Dolphin, Horse Children: Theseus, Triton, Polyphemus, Atlas, Pegasus, Orion and more Interesting Story: Has a hatred of Odysseus for blinding Poseidon’s son, the Cyclops Polyphemus. Roman Name: Neptune God of the Underworld The Dead, Riches Married to : Persephone Symbols: Serpent, Cerberus the Three Headed Dog Children: Zagreus, Macaria, possibly others Interesting Story: Hades tricked his “wife” Persephone into eating pomegranate seeds from the Underworld, binding her to him and forcing her to live in the Underworld for part of each year. -

Aletheia: the Orphic Ouroboros

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2020 Aletheia: The Orphic Ouroboros Glen McKnight Edith Cown University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Classics Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation McKnight, G. (2020). Aletheia: The Orphic Ouroboros. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1541 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1541 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Aletheia: The Orphic Ouroboros Glen McKnight Bachelor of Arts This thesis is presented in partial fulfilment of the degree of Bachelor of Arts Honours School of Arts & Humanities Edith Cowan University 2020 i Abstract This thesis shows how The Orphic Hymns function as a katábasis, a descent to the underworld, representing a process of becoming and psychological rebirth. -

Dionysos Mystes" by G

"Dionysos Mystes" by G. Rizzo; Zagreus, Studi sull' Orfismo by V. Macchioro Review by: E. Douglas van Buren The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 9 (1919), pp. 221-225 Published by: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/296011 . Accessed: 18/06/2014 02:54 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Roman Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 02:54:30 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions NOTICES OF RECENT PUBLICATIONS. 221 in the old system was that in its exclusive cult of memory it starved thought to death; the result of all the Virgilian paraphrasing, all the dictiones ethicae and artificial dis- putations, had been an extraordinary dearth of men able to concentrate on any real or new problem. The Church, by forcing men to think, restored a living interest in thought. It also brought history back into an honest connexion with fact; the first ecclesiastical chronicles were dull, but they were history, and neither mythology nor panegyric. -

O Oceanids (Ὠκεανίδες). the 'Holy Company' of Daughters of *Ocean and *Tethys, and Sisters of the River-Gods. Their N

O Oceanids (Ὠκεανίδες). The 'holy company' of daughters of *Ocean and *Tethys, and sisters of the river-gods. Their number varies, but Apollodorus names seven (Asia, *Styx, Electra, Doris, Eurynome, *Amphitrite, *Metis) and Hesiod forty-one, including, in addition to those mentioned by Apollodorus, *Calypso *Clymene and Philyra. Most of those named mated with gods (Amphitrite with Poseidon, Doris with Nereus for example) and produced important offspring (Athena was born from Metis and Zeus, Philyra mated with Kronos in the form of a horse and produced the centaur Chiron, Clymene was the mother of Prometheus, and also bore Phaethon to Helius the sun-god.). The sons of Ocean were the fresh-water rivers, but some of the daughters were sea-nymphs, others spirits of streams called after a characteristic of their water such as Ocyrrhoe ('swift-flowing') or Xanthe ('brownish-yellow'); Styx, unusually, was a female river deity, personifying the river of Hades. Calypso ruled over the island kingdom of Ogygia (but her parentage as a true Oceanid is disputed). Metis had the ability, common to sea-gods, of being able to change her shape, although she was little more than the personification of wisdom, swallowed by Zeus in order to absorb that wisdom and to contain any threat from the child with whom she was pregnant. Oceanids feature as the chorus in Prometheus Bound, a tragedy which is set at the north-eastern edge of the known world, and at a time before Zeus had consolidated his power. The Oceanids were part of the older, pre-Olympian race of gods, who had a role as consorts or mothers of other divinities, but were more often viewed anonymously as belonging to the vastness of the sea, to be placated in times of storm and turbulence. -

Plato's Orpheus: the Philosophical Appropriation of Orphic Formulae

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Foreign Languages & Literatures ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 6-9-2016 Plato's Orpheus: The hiP losophical Appropriation of Orphic Formulae Dannu Hütwohl Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/fll_etds Recommended Citation Hütwohl, Dannu. "Plato's Orpheus: The hiP losophical Appropriation of Orphic Formulae." (2016). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/fll_etds/20 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Foreign Languages & Literatures ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dannu J. Hutwohl Foreign Languages and Literatures Professor Lorenzo F. Garcia Jr. Professor Monica S. Cyrino Professor Osman Umurhan by THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico Acknowledgements I wish to extend a heart felt thanks to all the members of my thesis committee, without whom this project would not have been possible: first and foremost to my brilliant and inspiring advisor and mentor, Dr. Lorenzo F. Garcia Jr., for your endless patience, wisdom, and dedication; Just as the Orphic initiates would have been lost in the darkness of the Underworld without the help of their Gold Tablets, so too would I have been lost in this undertaking without the illuminating light of your golden advice. To Dr. Monica S. Cyrino, for your incredible editing skills and for always believing in and supporting me over the years in countless ways; Just as Demeter moved heaven and earth for Persephone, so too have you nurtured and championed my research. -

Game Narrative Review

Game Narrative Review ==================== Your name (one name, please): Scott Parker Your school: Sheridan College Your email: [email protected] Month/Year you submitted this review:04/2021 ==================== Game Title: HADES Platform: PC/Mac/Switch Genre: Roguelite, RPG, Action Release Date: September 17th, 2020 Developer: Supergiant Games Publisher: Supergiant Games Game Writer/Creative Director/Narrative Designer: Greg Kasavin Overview With a sword in hand, you take control of Zagreus as he attempts a daring escape from the Underworld against your father’s wishes. As the son of Hades, he grants you no mercy against his forces guarding the Underworld and makes every effort to make your time in hell….well, hell. Zagreus begins the game blissfully unaware of the complex relationships between his family members (and his true mother, Persephone). Through the events of HADES, Zagreus persists in his efforts of escaping the Greek Underworld initially to unite with the Olympians. Later, the player learns Zagreus’ efforts are actually to reunite with his true mother who abandoned him at birth, unknown to the Olympian gods. At nearly every turn, characters from nearly every walk and corner of the Greek world will attempt to aid Zagreus in his escape attempts—members of the House of Hades (i.e. Dusa, Achilles, Thanatos, Hypnos, Nyx, Orpheus), the Olympian gods (Zeus, Poseidon, Hermes, Dionysus, Athena, Artemis, Ares, Demeter, Aphrodite), and even souls confined to the depths of the Underworld (i.e. Skelly, Charon, Chaos, Sisyphus, Eurydice), often offering boons, resources and trinkets which Zagreus can use against the forces of the Underworld. Hades inevitably resorts to the various shades and monsters residing in the four regions of the underworld to prevent Zagreus’ escape. -

Orpheus and Orphism: Cosmology and Sacrifice at the Boundary

Orpheus and Orphism: Cosmology and Sacrifice at the Boundary Liz Locke An Interdisciplinary Prelude Knowledge is, in the final analysis, taxonomic, but a taxonomy that is allowed to merge with the object of study-which is reified so that it becomes a datum in its own right-must at best be stultifying. Were this not so, there would have been no intellectual change in human history. Thus, to see the particular reading of an ancient tragedy as refracted through a particular ideological prism, or to spell out the implications of a translator's vocabulary, syntax, and style-these things do not decrease our knowledge; they protect it. (Herzfeld 198359) I am fond of this passage by Michael Herzfeld because it points in so many directions at once. It points toward epistemology in that it asks us to examine the categorical taxonomies that underlie our assumptions about how we know what we think we know. It points toward cosmology in that it suggests that the world which produced ancient tragedy is still available to us as a precursive guide to our own sense of place in the universe. Epistemology, cosmology, and ideology have much in common: they attempt simultaneously to create and explain the bases from which we describe our knowledge of the world, of ourselves, and of the cognitive and social structures through which we circulate in the course of our lifetimes, our histories, and our projected futures. I am a folklorist because the study of folklore also points in so many directions at once. It recognizes that we cannot hope to understand much about our peculiar place in the universe without eventually taking all such questions into account. -

On Greek Religion and Mythology. the Demeter Myth

^be ©pen Court A MONTHLY MAGAZINE Bcvoteb to tbe Science of IRelfgfon, tbe IRelfgfon ot Science, an& tbe Bxtensfon of tbe IReltglous parliament li^ea Editor: Dr. Paul Carus. I E. C. Hbgeler. /tssormies. Assistant -j Editor: T. J. McCormack. ^^^^ Carus. VOL. XIV. (no. 11) November, 1900. NO. 534 CONTENTS: Frontispiece. The Farnese Herakies. On Greek Religion and Mythology. The Demeter Myth. —Orpheus. —Her- mes. —Prometheus. —Herakies. —Heroes, With Illustrations from the Monuments of Classical Antiquity. Editor .• 641 The Unshackling of the Spirit of Inquiry. A Sketch of the History of the Conflict Between Theology and Science. (Concluded.) With Por- traits of Roger Bacon, Giordano Bruno, and Montaigne. Dr. Ernst Krause (Carus Sterne), Berlin 659 The Eleusinian Mysteries. II. Primitive Rites of Illumination. The Rev. Charles James Wood, York, Penn 672 The International Arbitration Alliance. An Address Read Before the Peace Congress, Paris, 1900. With the Constitution Presented for Adop- tion by Mr. Hodgson Pratt. Dr. Moncure D. Conway, New York. 683 Christian Missions and European Politics in China. Prof. G. M. Fiamingo, Rome 689 Chinese Education. With Portraits of the Chinese Philosophers, Chow- kung, Chwang-tze, and Mencius. From Eighteenth Century Jap- anese Artists. Communicated 694 The Congress of the History of Religions and the Congress of Bourges. Lucien Arr6at 700 French Books on Philosophy and Science 701 The Ingersoll Lectureship on Immortality 702 Book Notices 704 CHICAGO ©be ©pen Court Ipublisbino Companie LONDON : Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd. Per copy, 10 cents (sixpence). Yearly, $1.00 (in the U. P. U., 58. 6d,). Copyright, 1900, by The Open Court Publishing Co. -

Orphism and Grafitti from Olbia Author(S): Leonid Zhmud' Source: Hermes, 120

Orphism and Grafitti from Olbia Author(s): Leonid Zhmud' Source: Hermes, 120. Bd., H. 2 (1992), pp. 159-168 Published by: Franz Steiner Verlag Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4476883 Accessed: 12-02-2016 07:32 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Franz Steiner Verlag is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Hermes. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 134.34.5.53 on Fri, 12 Feb 2016 07:32:10 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions ORPHISM AND GRAFITTI FROM OLBIA* The history of ancient Greek religion fortunately belongs to that branch of classicalstudies, that develops not only throughlasting discussions,but also thanks to the discovery of some new material, which sometimes resolves old arguments. So the finds of the last years that concern Orphismmake us turn once more to some disputedquestions that have for a long time interested the students of this religious movement. While the exavations in Italy added to alreadyknown Orphic golden plates one more of the same type', A. S. RUSJAEVA'Spublication of Orphic grafitti from Olbia (Vth century B.C.)2 was much more interesting.