The CUNY-Shanghai Library Faculty Exchange Program: Participants Remember, Reflect, and Reshape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shuang Zhang

June 2020 Shuang Zhang Department of Economics, University of Colorado Boulder Email: [email protected] Website: https://spot.colorado.edu/~shzh6533/index.html APPOINTMENTS 2020- Associate Professor of Economics (with tenure), University of Colorado Boulder 2013-2020 Assistant Professor of Economics, University of Colorado Boulder 2012-2013 SIEPR Postdoctoral Fellow, Stanford University AFFILIATIONS 2020- Faculty Research Fellow, National Bureau of Economic Research EDUCATION Ph.D. in Economics, Cornell University, 2012 M.A. in Economics, Fudan University, China, 2007 B.A. in Economics (with distinction), Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, China, 2004 RESEARCH INTERESTS Environment and Energy, Health, Development, China PUBLICATIONS “Willingness to Pay for Clean Air: Evidence from Air Purifier Markets in China” (with Koichiro Ito). Journal of Political Economy, 2020, 128 (5): 1627-1672. (Lead Article) “Land Reform and Sex Selection in China” (with Douglas Almond and Hongbin Li). Journal of Political Economy, 2019, 127 (2): 560-585. “The Limits of Political Meritocracy: Screening Bureaucrats Under Imperfect Verifiability” (with Juan Carlos Suárez Serrato and Xiao Yu Wang). Journal of Development Economics, 2019, 140: 223-241. “Quantifying Coal Power Plant Responses to Tighter SO2 Emissions Standards in China” (with Va- lerie Karplus and Douglas Almond). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2018, 115 (27): 7004-7009. “The Effects of High School Closure on Education and Labor Market Outcomes in Rural China”. Economic Development and Culture Change, 2018, 67 (1): 171-191. 1 WORKING PAPERS Reforming Inefficient Energy Pricing: Evidence from China (with Koichiro Ito), NBER WP 26853, 2020. Ambiguous Pollution Response to COVID-19 in China (with Douglas Almond and Xinming Du), NBER WP 27086, 2020. -

Journal of East Asian Libraries, No. 165, October 2017

Journal of East Asian Libraries Volume 2017 | Number 165 Article 1 10-2017 Journal of East Asian Libraries, No. 165, October 2017 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal BYU ScholarsArchive Citation (2017) "Journal of East Asian Libraries, No. 165, October 2017," Journal of East Asian Libraries: Vol. 2017 : No. 165 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal/vol2017/iss165/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of East Asian Libraries by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of East Asian Libraries Journal of the Council on East Asian Libraries No. 165, October 2017 CONTENTS From the President 3 Essay A Tribute to John Yung-Hsiang Lai 4 Eugene W. Wu Peer-Review Articles An Overview of Predatory Journal Publishing in Asia 8 Jingfeng Xia, Yue Li, and Ping Situ Current Situation and Challenges of Building a Japanese LGBTQ Ephemera Collection at Yale Haruko Nakamura, Yoshie Yanagihara, and Tetsuyuki Shida 19 Using Data Visualization to Examine Translated Korean Literature 36 Hyokyoung Yi and Kyung Eun (Alex) Hur Managing Changes in Collection Development 45 Xiaohong Chen Korean R me for the Library of Congress to Stop Promoting Mccune-Reischauer and Adopt the Revised Romanization Scheme? 57 Chris Dollŏmaniz’atiŏn: Is It Finally Ti Reports Building a “One- 85 Paul W. T. Poon hour Library Circle” in China’s Pearl River Delta Region with the Curator of the Po Leung Kuk Museum 87 Patrick Lo and Dickson Chiu Interview 1 Web- 93 ProjectCollecting Report: Social Media Data from the Sina Weibo Api 113 Archiving Chinese Social Media: Final Project Report New Appointments 136 Book Review 137 Yongyi Song, Editor-in-Chief:China and the Maoist Legacy: The 50th Anniversary of the Cultural Revolution文革五十年:毛泽东遗产和当代中国. -

2019 Year Book.Pdf

2019 Contents Preface / P_05> Overview / P_07> SICA Profile / P_15> Cultural Performances and Exhibitions, 2019 / P_19> Foreign Exchange, 2019 / P_45> Academic Conferences, 2019 / P_67> Summary of Cultural Exchanges and Visits, 2019 / P_77> 「Offerings at the First Day of Year」(detail) by YANG Zhengxin Sea Breeze: Exhibition of Shanghai-Style Calligraphy and Painting Preface This year marks the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Over the past 70 years, the Chinese culture has forged ahead regardless of trials and hardships. In the course of its inheritance and development, the Chinese culture has stepped onto the world stage and found her way under spotlight. The SICA, established in the golden age of reform and opening-up, has been adhering to its mission of “strengthening mutual understanding and friendly cooperation between Shanghai and other countries or regions through international cultural exchanges in various areas, so as to promote the economic development, scientific progress and cultural prosperity of the city” for more than 30 years. It has been exploring new modes of international exchange and has been actively engaging in a variety of international culture exchanges on different levels in broad fields. On behalf of the entire staff of the SICA, I hereby would like to extend our sincere gratitude for the concern and support offered by various levels of government departments, Council members of the SICA, partner agencies and cultural institutions, people from all circles of life, and friends from both home and abroad. To sum up our work in the year 2019, we share in this booklet a collection of illustrated reports on the programs in which we have been involved in the past year. -

1 Zhirong “Jerry” Zhao

Updated 03/16/2020 ZHIRONG “JERRY” ZHAO Gross Family Professor, Public & Nonprofit Management Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs, University of Minnesota (UMN) 301 19th Avenue South, Minneapolis, MN 55455 [email protected], 612-625-7318 (phone) BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION Education 2005 Ph.D. of Public Administration, University of Georgia (UGA), Athens 1997 Master of Urban Planning, Tongji University, Shanghai, China 1993 Bachelor of Urban Planning, Tongji University, Shanghai, China Academic Positions 2019- pres. Chair Leadership & Management Area, Humphrey School of Public Affairs, UMN 2019–pres. Gross Family Professor, Humphrey School of Public Affairs, UMN 2017- pres. Director, Master of Public Policy Program, Humphrey School of Public Affairs, UMN 2017- pres. Founding Director, Institute for Urban & Regional Infrastructure Finance, UMN 2012–2019 Associate Professor, Humphrey School of Public Affairs, UMN 2007–2011 Assistant Professor, Humphrey School of Public Affairs, UMN 2005–2007 Director, Political Science Internship Program, Eastern Michigan University 2005–2007 Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Eastern Michigan University Professional Experience 2002–2005 Education Program Specialist, Carl Vinson Institute of Government, UGA 1993–1998 Assistant Urban Planner, Xiamen Academy of Urban Planning & Design, China Awards and Honors 2020 SCPA Leadership Award, American Society for Public Administration (ASPA) 2018 Outstanding Services Award, Center for Transportation Studies, UMN 2018 Leadership Award, China-America -

A Large-Scale Clinical Validation Study Using Ncapp Cloud Plus

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.07.20163402; this version posted August 11, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . A Large-Scale Clinical Validation Study Using nCapp Cloud Plus Terminal by Frontline Doctors for the Rapid Diagnosis of COVID-19 and COVID-19 pneumonia in China Dawei Yang, M.D.1,20,25#, Tao Xu, M.D.2,18#, Xun Wang, M.D.3,21#, Deng Chen, M.S.4#, Ziqiang Zhang, M.D.5#, Lichuan Zhang, M.D.6#, Jie Liu, M.D.1,25, Kui Xiao, M.D.7, Li Bai, M.D.8, Yong Zhang, M.D.1,25, Lin Zhao, M.D.9, Lin Tong, M.D.1, Chaomin Wu, M.D.10,23, Yaoli Wang, M.D.12, Chunling Dong, M.D.12, Maosong Ye, M.D.1,25, Yu Xu, M.D.,8,24, Zhenju Song, M.D.13, Hong Chen, M.D.14, Jing Li1,25, Jiwei Wang, Ph.D.4, Fei Tan, M.S.15, Hai Yu, M.S.15, Jian Zhou, Ph.D.1,25, Jinming Yu, Ph.D.4, Chunhua Du, M.D.2, Hongqing Zhao, M.D.3, Yu Shang, M.D.16, Linian Huang17, Jianping Zhao, M.D.18, Yang Jin, M.D.19, Charles A. Powell, M.D.20, Yuanlin Song, M.D.1,25*, Chunxue Bai, M.D.1,25* 1. -

A Legacy in Chinese Education History, Or a Solution for Modern Undergraduates in China?

Journal of Education and Learning; Vol. 9, No. 6; 2020 ISSN 1927-5250 E-ISSN 1927-5269 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Chinese Shuyuan: A Legacy in Chinese Education History, or a Solution for Modern Undergraduates in China? Zhen Zeng1 1 School of Foreign Studies, Guangxi Normal University, Guilin, Guangxi, China Correspondence: Zhen Zeng, 82 Liuhe Road, Qixing District, Guilin, Guangxi, Postal Code: 541004, China. E-mail: [email protected] Received: September 28, 2020 Accepted: November 19, 2020 Online Published: November 26, 2020 doi:10.5539/jel.v9n6p173 URL: https://doi.org/10.5539/jel.v9n6p173 Abstract The paper looked into concepts claimed to be essence of Chinese residential college, an on-going institution presumed to be a solution towards undergraduates’ issues in some pioneer universities in China. It’s analyzed that Chinese residential college today in China is not a Shuyuan that was ever striving as a unique education mode in ancient China, even if it’s named after Shuyuan in Chinese, concerning on its nature, function and goal, while it’s not a conventional residential college in English speaking countries neither. By investigation and comparison of its origin, function and features among Shuyuan and Chinese residential college, the spirit of development of a human with goodness and well-being through pursuit of knowledge and culture inherited and transmitted in Shuyuan is unearthed, which is supposed to be the resource of inspiration when the pioneer universities and educators designed and operate residential college on Chinese campus, though the effects couldn’t be accounted as appealing as what Shuyuan produced in ancient China. -

Shanghai Before Nationalism Yexiaoqing

East Asian History NUMBER 3 . JUNE 1992 THE CONTINUATION OF Papers on Fa r EasternHistory Institute of Advanced Studies Australian National University Editor Geremie Barme Assistant Editor Helen 1.0 Editorial Board John Clark Igor de Rachewiltz Mark Elvin (Convenor) Helen Hardacre John Fincher Colin Jeffcott W.J.F. Jenner 1.0 Hui-min Gavan McCormack David Marr Tessa Morris-Suzuki Michael Underdown Business Manager Marion Weeks Production Oahn Collins & Samson Rivers Design Maureen MacKenzie, Em Squared Typographic Design Printed by Goanna Print, Fyshwick, ACT This is the second issue of EastAsian History in the series previously entitled Papers on Far Eastern History. The journal is published twice a year. Contributions to The Editor, EastAsian History Division of Pacific and Asian History, Research School of Pacific Studies Australian National University, Canberra ACT 2600, Australia Phone +61-6-2493140 Fax +61-6-2571893 Subscription Enquiries Subscription Manager, East Asian History, at the above address Annual Subscription Rates Australia A$45 Overseas US$45 (for two issues) iii CONTENTS 1 Politics and Power in the Tokugawa Period Dani V. Botsman 33 Shanghai Before Nationalism YeXiaoqing 53 'The Luck of a Chinaman' : Images of the Chinese in Popular Australian Sayings Lachlan Strahan 77 The Interactionistic Epistemology ofChang Tung-sun Yap Key-chong 121 Deconstructing Japan' Amino Yoshthtko-translat ed by Gavan McCormack iv Cover calligraphy Yan Zhenqing ���Il/I, Tang calligrapher and statesman Cover illustration Kazai*" -a punishment -

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction

Shanghai, China Overview Introduction The name Shanghai still conjures images of romance, mystery and adventure, but for decades it was an austere backwater. After the success of Mao Zedong's communist revolution in 1949, the authorities clamped down hard on Shanghai, castigating China's second city for its prewar status as a playground of gangsters and colonial adventurers. And so it was. In its heyday, the 1920s and '30s, cosmopolitan Shanghai was a dynamic melting pot for people, ideas and money from all over the planet. Business boomed, fortunes were made, and everything seemed possible. It was a time of breakneck industrial progress, swaggering confidence and smoky jazz venues. Thanks to economic reforms implemented in the 1980s by Deng Xiaoping, Shanghai's commercial potential has reemerged and is flourishing again. Stand today on the historic Bund and look across the Huangpu River. The soaring 1,614-ft/492-m Shanghai World Financial Center tower looms over the ambitious skyline of the Pudong financial district. Alongside it are other key landmarks: the glittering, 88- story Jinmao Building; the rocket-shaped Oriental Pearl TV Tower; and the Shanghai Stock Exchange. The 128-story Shanghai Tower is the tallest building in China (and, after the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, the second-tallest in the world). Glass-and-steel skyscrapers reach for the clouds, Mercedes sedans cruise the neon-lit streets, luxury- brand boutiques stock all the stylish trappings available in New York, and the restaurant, bar and clubbing scene pulsates with an energy all its own. Perhaps more than any other city in Asia, Shanghai has the confidence and sheer determination to forge a glittering future as one of the world's most important commercial centers. -

Ninghua, ZHONG (钟宁桦)

Ninghua, ZHONG (钟宁桦) Professor, Economics and Finance School of Economics and Management Tongji University, Shanghai [email protected]; [email protected] Academic Background PhD in Finance, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, January 2013 PhD Committee: Sudipto Dasgupta, Vidan K. Goyal, K. C. John Wei, Albert Park, Zhigang Tao MA in Economics, Peking University, China Center for Economic Research, July 2008 Adviser: Yang Yao BA in Economics with highest distinction, Fudan University, School of Economics, July 2005 GPA: 3.82 out of 4.00 Class rank: 1 out of 109 Current Academic Appointment Professor, School of Economics and Management, Tongji University Promoted to Full Professor in December 2015 due to my exceptional performance Promoted to Associate Professor in June 2013 shortly after joining the university in March 2013 Teaches at one of the premier Executive MBA programs in the world (Tongji University/ENPC), ranked 68th in 2014 by the Financial Times Research interests include (a) applied microeconomics studies in the fields of labor economics, corporate finance, and empirical asset pricing and (b) Chinese economic reform and development Ningua, ZHONG (钟宁桦) 1 Publications and Working Papers—English As of December 2015, Google Scholar calculated 225 citations of my papers: On China’s Labor Market Issues (Papers in this field are developed from my master thesis) “Unions and Workers’ Welfare in Chinese Firms” (with Yang Yao), [download from JSTOR] Journal of Labor Economics 31, no. 3 (2013): 633–67. -

Participants: (In Order of the Surname)

Participants 31 Participants: (in order of the surname) Yansong Bai yyyòòòttt: Jilin University, Changchun. E-mail: [email protected] Jianhai Bao ïïï°°°: Central South University, Changsha. E-mail: [email protected] Chuanzhong Chen •••DDD¨¨¨: Hainan Normal University, Haikou. E-mail: [email protected] Dayue Chen •••ŒŒŒ: Peking University, Beijing. E-mail: [email protected] Haotian Chen •••hhhUUU: Jilin University, Changchun. E-mail: [email protected] Longyu Chen •••999ˆˆˆ: Peking University, Beijing. E-mail: [email protected] Man Chen •••ùùù: Capital Normal University, Beijing. E-mail: [email protected] Mu-Fa Chen •••777{{{: Beijing Normal University, Beijing. E-mail: [email protected] Shukai Chen •••ÓÓÓppp: Beijing Normal University, Beijing. E-mail: [email protected] Xia Chen •••ggg: Jilin University, Changchun; University of Tennessee, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Xin Chen •••lll: Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai. E-mail: [email protected] Xue Chen •••ÆÆÆ: Capital Normal University, Beijing. E-mail: [email protected] Zengjing Chen •••OOO¹¹¹: Shandong University, Jinan. E-mail: [email protected] 32 Participants Huihui Cheng §§§¦¦¦¦¦¦: North China University of Water Resources and Electric Power, Zhengzhou E-mail: [email protected] Lan Cheng §§§===: Central South University, Changsha. E-mail: [email protected] Zhiwen Cheng §§§“““>>>: Beijing Normal University, Beijing. E-mail: [email protected] Michael Choi éééRRRZZZ: The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen. E-mail: [email protected] Bowen Deng """ÆÆÆ©©©: Jilin University, Changchun. E-mail: [email protected] Changsong Deng """ttt: Wuhan University, Wuhan. E-mail: [email protected] Xue Ding ¶¶¶ÈÈÈ: Jilin University, Changchun. -

EMA Program in Chinese Philosophy and Culture

EMA Program in Chinese Philosophy and Culture I. Academic Programs Overview These programs are aimed to offer opportunities of learning Chinese and studying Chinese philosophy to overseas postgraduates or college juniors and seniors who have not yet been able to master the Chinese language. In addition to Chinese language classes, these programs offer courses on Chinese philosophy as well as other related courses in English at Fudan University. Fudan University is a leading institution of higher education in China, and is experienced with and renowned for educating overseas students. The School of Philosophy at Fudan is a top philosophy program in China. The university is located in Shanghai, the most dynamic city in China that belongs to a region that is rich in Chinese traditions and cultures. It has been 10 years since these programs were launched in 2011, and 105 students have been enrolled in either the M.A. program (87 students) and the visiting student program (18 students). They are from 35 countries (the U.S., Canada, Puerto Rico, Barbados, Uruguay, Brazil, Chile, Australia, the U.K., Ireland, the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, France, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Iceland, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Montenegro, Slovenia, Russia, Israel, Turkey, Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia, India, Bangladesh, and Gambia, with student from North America and Europe forming the majority of the student body), and many of them are top students in their classes, majoring in philosophy, classics, and/or East Asian or Chinese studies. The above facts make these programs simply the most successful of their kind (English-based post-graduate programs in Chinese philosophy) in mainland China. -

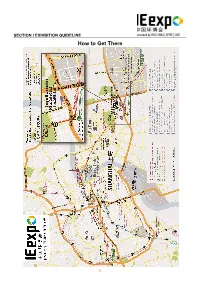

How to Get There

SECTION I EXHIBITION GUIDELINE How to Get There 12 SECTION I EXHIBITION GUIDELINE How to Get There (cont’d) Shanghai Metro Map 13 SECTION I EXHIBITION GUIDELINE How to Get There (cont’d) SNIEC is strategically located in Pudong‘s key economic development zone. There is a public traffic interchange for bus and metro, , one named “Longyang Road Station“ about 10-min walk from the station to fairground, and one named “Huamu Road Station“ about 1-min walk from the station to fairground. By flight The expo centre is located half way between Pudong International Airport and Hongqiao Airport, 35 km away from Pudong International Airport to the east, and 32 km away from Hongqiao Airport to the west. You can take the airport bus, maglev or metro directly to the expo center. From Pudong International Airport By taxi By Transrapid Maglev: from Pudong International Airport to Longyang Road Take metro line 2 to Longyang Road Station to change line 7 to Huamu Road Station, 60 min. By Airport Line Bus No. 3: from Pudong Int’l Airport to Longyang Road, 40 min, ca. RMB 20. From Hongqiao Airport By taxi Take metro line 2 to Longyang Road Station to change line 7 to Huamu Road Station, 60 min. By train From Shanghai Railway Station or Shanghai South Railway Station please take metro line1 to People’s Square, then take metro line 2 toward Pudong International Airport Station and get off at Longyang Road Station to change line7 to Huamu Road Station. From Hongqiao Railway Station, please take metro line 2 to Longyang Road Station and change line 7 to Huamu Road Station.