Harold Agnew, Physicist, Atomic Bomb Everyman William H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biographies of Edison Lecturers

Harold Agnew, UC San Diego Professor Agnew was born in Denver, Colorado, in 1921. He received a B.A. in chemistry from the University of Denver in 1942. He joined Fermi’s research group at Chicago as a graduate student in 1942. He was sent to Columbia and then moved with Fermi back to Chicago and participated in the construction of the pile under the west stands of Stagg Field. He was a witness at the initiation of the first controlled nuclear chain reaction on December 2, 1942. Following this event he moved to Los Alamos in 1943. He participated at the Trinity test, the first test explosion of a nuclear bomb at the White Sands Missile test facility in New Mexico. On August 6, 1945; he flew with the 509th Composite Group to Hiroshima with Luis Alvarez (UC Berkeley) and Bernie Waldman (Notre Dame). He participated at the measurement of the yield of the first atomic bomb directly from air over the target. In 1946 he returned to Chicago to complete his graduate studies and received a Ph.D. in 1949 under Fermi’s direction. Following his stay at Chicago he returned to Los Alamos in the Physics Division and eventually became the Weapons Division leader (1964-70). In 1970 he became director of the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. In 1979 he retired and became president of General Atomics and retired in 1983. Harold Agnew was scientific advisor to SACEUR at NATO (1961-64), a member of the President’s Science Advisory Committee (1965-73), and a White House science councilor (1982-89). -

Annual Report 2013.Pdf

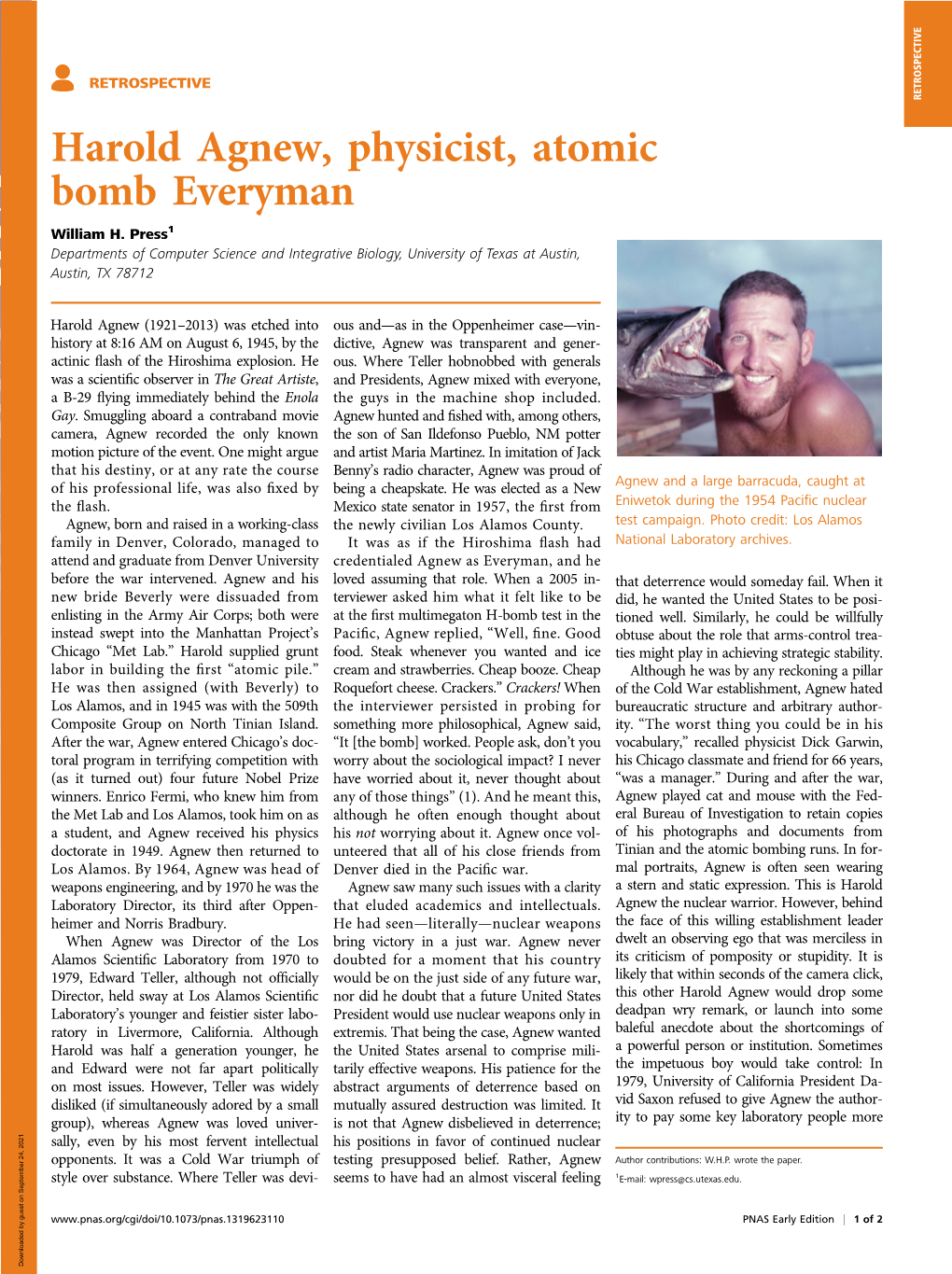

ATOMIC HERITAGE FOUNDATION Preserving & Interpreting Manhattan Project History & Legacy preserving history ANNUAL REPORT 2013 WHY WE SHOULD PRESERVE THE MANHATTAN PROJECT “The factories and bombs that Manhattan Project scientists, engineers, and workers built were physical objects that depended for their operation on physics, chemistry, metallurgy, and other nat- ural sciences, but their social reality - their meaning, if you will - was human, social, political....We preserve what we value of the physical past because it specifically embodies our social past....When we lose parts of our physical past, we lose parts of our common social past as well.” “The new knowledge of nuclear energy has undoubtedly limited national sovereignty and scaled down the destructiveness of war. If that’s not a good enough reason to work for and contribute to the Manhattan Project’s historic preservation, what would be? It’s certainly good enough for me.” ~Richard Rhodes, “Why We Should Preserve the Manhattan Project,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, May/June 2006 Photographs clockwise from top: J. Robert Oppenheimer, General Leslie R. Groves pinning an award on Enrico Fermi, Leona Woods Marshall, the Alpha Racetrack at the Y-12 Plant, and the Bethe House on Bathtub Row. Front cover: A Bruggeman Ranch property. Back cover: Bronze statues by Susanne Vertel of J. Robert Oppenheimer and General Leslie Groves at Los Alamos. Table of Contents BOARD MEMBERS & ADVISORY COMMITTEE........3 Cindy Kelly, Dorothy and Clay Per- Letter from the President..........................................4 -

Nuclear Weapons Technology 101 for Policy Wonks Bruce T

NUCLEAR WEAPONS TECHNOLOGY FOR POLICY WONKS NUCLEAR WEAPONS TECHNOLOGY 101 FOR POLICY WONKS BRUCE T. GOODWIN BRUCE T. GOODWIN BRUCE T. Center for Global Security Research Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory August 2021 NUCLEAR WEAPONS TECHNOLOGY 101 FOR POLICY WONKS BRUCE T. GOODWIN Center for Global Security Research Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory August 2021 NUCLEAR WEAPONS TECHNOLOGY 101 FOR POLICY WONKS | 1 This work was performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in part under Contract W-7405-Eng-48 and in part under Contract DE-AC52-07NA27344. The views and opinions of the author expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC. ISBN-978-1-952565-11-3 LCCN-2021907474 LLNL-MI-823628 TID-61681 2 | BRUCE T. GOODWIN Table of Contents About the Author. 2 Introduction . .3 The Revolution in Physics That Led to the Bomb . 4 The Nuclear Arms Race Begins. 6 Fission and Fusion are "Natural" Processes . 7 The Basics of the Operation of Nuclear Explosives. 8 The Atom . .9 Isotopes . .9 Half-life . 10 Fission . 10 Chain Reaction . 11 Critical Mass . 11 Fusion . 14 Types of Nuclear Weapons . 16 Finally, How Nuclear Weapons Work . 19 Fission Explosives . 19 Fusion Explosives . 22 Staged Thermonuclear Explosives: the H-bomb . 23 The Modern, Miniature Hydrogen Bomb . 25 Intrinsically Safe Nuclear Weapons . 32 Underground Testing . 35 The End of Nuclear Testing and the Advent of Science-Based Stockpile Stewardship . 39 Stockpile Stewardship Today . 41 Appendix 1: The Nuclear Weapons Complex . -

7.4 News 684 MH

news Pope praised for CHILD/AP partial conciliation of B. science and religion Quirin Schiermeier,Munich Catholic researchers and bioethicists have responded to the death of Pope John Paul II with tributes to his efforts to achieve reconciliation between faith and science. And some are optimistic that his successor will keep on the same path. The Polish Pope had a strong personal interest in science and worked to reduce hostility between the scientific community and the Roman Catholic Church. Nonetheless, his strict rejection Water bombs: US submarines such as the Virginia are armed with W76 thermonuclear warheads. of abortion, embryonic stem-cell research and contraception, including the distribution of condoms to help Nuclear chiefs scotch story contain AIDS, drew him into conflict with some scientists. AIDS activist groups around the on frailty of ageing warheads world still condemn John Paul’s refusal to endorse the use of condoms.“It should Geoff Brumfiel,Washington told the The New York Times.Morse did not not be forgotten that millions have died Senior weapons scientists emphatically respond to Nature’s requests for an interview. in Africa as a result of this theological denied a report this week that the most Other scientists familiar with the weapon rigidity,”the London-based Independent important US nuclear warhead has a design dispute Morse’s assertions. “I think he’s newspaper said in an editorial. fault that could make it unreliable. wrong,” says Richard Garwin, a prominent However, John Paul frequently The New York Times reported on 3 April former hydrogen-bomb designer. Agnew, discussed scientific matters with such that the W76, a thermonuclear warhead who was present at several tests of the W76, luminaries as Stephen Hawking, who is launched from submarines, has a flaw in the says that it never failed to detonate. -

Character List

Character List - Bomb Use this chart to help you keep track of the hundreds of names of physicists, freedom fighters, government officials, and others involved in the making of the atomic bomb. Scientists Political/Military Leaders Spies Robert Oppenheimer - Winston Churchill -- Prime Klaus Fuchs - physicist in designed atomic bomb. He was Minister of England Manhattan Project who gave accused of spying. secrets to Russia Franklin D. Roosevelt -- Albert Einstein - convinced President of the United States Harry Gold - spy and Courier U.S. government that they for Russia KGB. Narrator of the needed to research fission. Harry Truman -- President of story the United States Enrico Fermi - created first Ruth Werner - Russian spy chain reaction Joseph Stalin -- dictator of the Tell Hall -- physicist in Soviet Union Igor Korchatov -- Russian Manhattan Project who gave physicist in charge of designing Adolf Hitler -- dictator of secrets to Russia bomb Germany Haakon Chevalier - friend who Werner Reisenberg -- Leslie Groves -- Military approached Oppenheimer about German physicist in charge of leader of the Manhattan Project spying for Russia. He was designing bomb watched by the FBI, but he was not charged. Otto Hahn -- German physicist who discovered fission Other scientists involved in the Manhattan Project: Aage Niels Bohr George Kistiakowsky Joseph W. Kennedy Richard Feynman Arthur C. Wahl Frank Oppenheimer Joseph Rotblat Robert Bacher Arthur H. Compton Hans Bethe Karl T. Compton Robert Serber Charles Critchfield Harold Agnew Kenneth Bainbridge Robert Wilson Charles Thomas Harold Urey Leo James Rainwater Rudolf Pelerls Crawford Greenewalt Harold DeWolf Smyth Leo Szilard Samuel K. Allison Cyril S. Smith Herbert L. Anderson Luis Alvarez Samuel Goudsmit Edward Norris Isidor I. -

Rare Books, Autographs & Maps

RARE BOOKS, AUTOGRAPHS & MAPS Wednesday, April 17, 2019 NEW YORK RARE BOOKS, AUTOGRAPHS & MAPS AUCTION Wednesday, April 17, 2019 at 10am EXHIBITION Saturday, April 13, 10am – 5pm Sunday, April 14, Noon – 5pm Monday, April 15, 10am – 7pm Tuesday, April 16, 10am – 4pm LOCATION Doyle 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com INCLUDING PROPERTY CONTENTS FROM THE ESTATES OF Printed & Manuscript Americana 1 - 50 Marian Clark Adolphson, CT Maps 51 - 57 Frances “Peggy” Brooks Autographs 58 - 70 Elizabeth and Donald Ebel Manuscripts 71 - 74 Elizabeth H. Fuller Early Printed Books 75 - 97 Robin Gottlieb Fine Bindings 98 - 107 Arnold ‘Jake’ Johnson Automobilia 108 - 112 George Labalme, Jr. Color Plate & Plate Books Including 113 - 142 Peter Mayer Science & Natural History Suzanne Schrag Travel & Sport 143 - 177 Barbara Wainscott Children’s Literature 178 - 192 Illustration Art 193 - 201 20th Century Illustrated Books 202 - 225 19th Century Illustrated Books 226 - 267 INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM Modern Literature 268 - 351 A Gentleman A Palm Beach Collector Glossary I A Maine Collector Conditions of Sale II The Collection of Rudolf Serkin Terms of Guarantee IV Information on Sales & Use Tax V Buying at Doyle VI Selling at Doyle VIII Auction Schedule IX Company Directory XI Absentee Bid Form XII Lot 167 Printed & Manuscript Americana 1 4 AMERICAN FLAG A large 35 star American Flag. Cotton or linen flag, the canton [CALIFORNIA - BANKING] with 35 stars, likely Civil War era, approximately 68 x 136 inches or Early and rare ledger of the Exchange Bank of Elsinore. 5 1/2 x 11 feet (172 x 345 cm); the canton 36 x 51 inches (91 x 129 cm), August 1889-November 1890. -

Download Chapter 68KB

Memorial Tributes: Volume 21 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 21 HAROLD M. AGNEW 1921–2013 Elected in 1976 “Pioneering contributions in weapons engineering and combining science and engineering into effective technology.” BY RICARDO B. SCHWARZ HAROLD MELVIN AGNEW, a scientist who worked on the Manhattan Project that gave the United States its first atomic bomb and who later became the third director of Los Alamos National Laboratory, died September 29, 2013, at his home in Solana Beach, California. He was 92. He was born March 28, 1921, in Denver, the only child of a stonecutter father and homemaker mother. He attended South Denver High School and the University of Denver, where he majored in chemistry. After the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor brought the United States into World War II, Agnew and his girlfriend, Beverly Jackson, attempted to join the US Army Air Corps together. But Joyce Stearns, head of the Physics Department at the University of Denver, persuaded them to instead join him at the University of Chicago, where Stearns became deputy head of the Metallurgical Laboratory. In Chicago, Harold worked with Enrico Fermi and others on the construction of Chicago Pile-1, the first graphite- moderated nuclear reactor. Initially, he worked on instrumen- tation, calibrating Geiger counters, and then on stacking the graphite bricks that formed the reactor’s neutron moderator. On December 2, 1942, he witnessed the first self-sustained nuclear chain reaction when Pile-1 went critical. 3 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 21 4 MEMORIAL TRIBUTES After these successful tests, he and Beverly, now married, followed Fermi and others to Los Alamos to participate in the Manhattan Project for the development of a nuclear bomb. -

Trinity Transcript

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES Committee on International Security and Arms Control 60th Anniversary of Trinity: First Manmade Nuclear Explosion, July 16, 1945 PUBLIC SYMPOSIUM July 14, 2005 National Academy of Sciences Auditorium 2100 C Street, NW Washington, DC Proceedings By: CASET Associates, Ltd. 10201 Lee Highway, Suite 180 Fairfax, VA 22030 (703) 352-0091 CONTENTS PAGE Introductory Remarks Welcome: Ralph Cicerone, President, The National Academies (NAS) 1 Introduction: Raymond Jeanloz, Chair, Committee on International Security and Arms Control (CISAC) 3 Roundtable Discussion by Trinity Veterans Introduction: Wolfgang Panofsky, Chair 5 Individual Statements by Trinity Veterans: Harold Agnew 10 Hugh Bradner 13 Robert Christy 16 Val Fitch 20 Don Hornig 24 Lawrence Johnston 29 Arnold Kramish 31 Louis Rosen 35 Maurice Shapiro 38 Rubby Sherr 41 Harold Agnew (continued) 43 1 PROCEEDINGS 8:45 AM DR. JEANLOZ: My name is Raymond Jeanloz, and I am the Chair of the Committee on International Security and Arms Control that organized this morning’s symposium, recognizing the 60th anniversary of Trinity, the first manmade nuclear explosion. I will be the moderator for today’s event, and primarily will try to stay out of the way because we have many truly distinguished and notable speakers. In order to allow them the maximum amount of time, I will only give brief introductions and ask that you please turn to the biographical information that has been provided to you. To start with, it is my special honor to introduce Ralph Cicerone, the President of the National Academy of Sciences, who will open our meeting with introductory remarks. He is a distinguished researcher and scientific leader, recently serving as Chancellor of the University of California at Irvine, and his work in the area of climate change and pollution has had an important impact on policy. -

The Yields of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki Nuclear Explosions

Los Alamos National Laboramry Is operated by the University d Csllfornla for thsi United States department” of %rgy under contract “W-7405 -ENG-36. i .. ... .?...-----.-,- - . I —. 11%)~~ LOS AIENTIOS NationalLaboratory I . .. .. .. .... .. ... <,.. ., .. ,..’ ., . ...’ .- ..,,-- -,. ,. ,,. , ~. , r“ ., .. ,,. ~,-.,; -., - . .-. ,. .,, ,. .. ,. .. “;. .: . .“ . .... 1. \, , ,.. Ttr&”rs’&r was p~~”red & an accoun; ;fwork s&n”&~”bYariagency of the United Stati Govemmcn!. Neither tire (Jrritcd Mates Government nor any agency ther@, nor any ofthcir employees, makes any warranty, >xpressor implied, or assure= any legal Ikbiiity or re@mrst%iIity ror the accuracy, completeness, w u~fulp~ ofa~ information, ap6aralus, product, or p~<ess ditilosed, or represents that its usewould not inf~ngc privately owned @rts. Reference herein to any s~i@ commercial product, py or service by h%dc name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply ISS egdome.rne~t, !reornrnen~qtion. ,> or. fav@r&. b~,!hc Unit@ S_&aI.~-Coye-~qgl,or arq agency thereoc Thc - sd~~d opirdons ofaulhors expressed herein do not necessarily ssateor refleet those of the United Ssates . Government or any ageney thereof. c:,, ,. .t. +- .- ,,’. I . .. ,, , y.t ,~*,’.’!,~,..- , f , .,..-, LA-8819 UC-34 Issued: September 1985 The Yields of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki Nuclear Explosions — .— -. -.. -.. Los Alamos National Laboratory .~~ ~b~~~ LosAla.os,Ne..e.ic.87545 — THE YIELDS OF THE HIROSHIMA AND NAGASAKI EXPLOSIONS by John Malik ABSTRACT A deterministic estimate of the nuclear radiation fields from the Hiroshima and Nagasaki nuclear weapon explosions requires the yields of these explosions. The yield of the Nagasaki explosion is rather well established by both fireball and radiochemical data from other tests as 21 kt. There are no equivalent data for the Hiroshima explosion. -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Publishing Words to Prevent Them from Becoming True: The Radical Praxis of Günther Anders Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5nr2z210 Author Costello, Daniel Christopher Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Publishing Words to Prevent Them from Becoming True: The Radical Praxis of Günther Anders DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Comparative Literature by Daniel C. Costello Dissertation Committee: Professor Jane O. Newman, Chair Professor Emeritus Alexander Gelley Associate Professor Kai Evers 2014 © 2014 Daniel C. Costello TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgments vi Curriculum Vitae vii Abstract of the Dissertation viii INTRODUCTION I. A Writerly Life a. Beginnings 1 b. A Note on Style 13 c. Prelude 19 CHAPTER ONE: COMPETENCE AND AUTHORITY I. Introductions a. The Promethean Discrepancy 25 b. Network and Actor-Network Theories 29 c. Archives and the Occasional Philosophy 31 II. Historical Contexts: The Scientists’ Movement a. Genesis 34 b. One World Government 37 c. The Changing Role of Science 44 d. Generational Outcomes 51 III. Backgrounds: Anders and the Bomb a. Wars and Exile 55 b. Return to Vienna 62 IV. Historical Contexts: The Second Wave a. Fallout 65 b. Forms: Diary, Fable, Dialog, and Commandment 69 c. Groundwork to Praxis 73 V. Organizational Work a. Pursuing Scientists 81 ii b. A Pugwash for the Humanities 86 VI. Conclusions 88 CHAPTER TWO: THE CASE OF CLAUDE EATHERLY I. Introductions a. -

The Oppenheimer Years 1943-1945 6

" . .When you come right down to it the reason that we did this job is because it was an organic necessity. If you are a scientist you cannot stop such a thing . You believe that it is good to find out how the world works . [and] to turn over to mankind at large the greatest possible power to control the world and to deal with it according to its lights and its values. " . I think it is true to say that atomic weapons are a peril which affect everyone in the world, and in that sense a completely common problem . I think that in order to handle this common problem there must be a complete sense of community responsibility. " . The one point I want to hammer home is what an enormous change in spirit is involved. There are things which we hold very dear, and I think rightly hold very dear; I would say that the word democracy perhaps stood for some of them as well as any other word. There are many parts of the world in which there is no democracy . And when I speak of a new spirit in international affairs I mean that even to these deepest of things which we cherish, and for which Americans have been willing to die—and certainly most of us would be willing to die—even in these deepest things, we realize that there is something more profound than that; namely the common bond with other men everywhere . .“ J. Robert Oppenheimer speech to the Association of Los Alamos Scientists Los Alamos November 2, 1945 Excerpts from a speech to the Association of Los Alamos Scientists in Los Alamos, New Mexico, on November 2, 1945. -

Highlights of the Laboratory's Anniversary Celebration

Highlights of the Laboratory’s Anniversary Celebration Historians mark the beginning of Los Alamos National Laboratory with two dates—the initial meeting of J. Robert Oppenheimer’s Scientific Committee in Los Alamos on March 6, 1943, and the signing of the first oper- ating contract between the federal government and the University of California on April 20, 1943. The 60th anniversary of the Laboratory was commemorated with numerous activities, starting in April and concluding in September. Planned by a task force of volunteers, the anniversary activities celebrated the Laboratory’s historic contributions and accomplishments; appreciated people, communities, and institutions as enablers of the Laboratory; and anticipated future directions and challenges. The winning entry in a Laboratory-wide slogan Celebration Kickoff contest provided the 60th anniversary theme, “Ideas That Change the World.” Pete Nanos, then Interim Director, kicked off the anniversary celebrations with an address to Celebrate, appreciate, and anticipate—these words sum up the mood of the the Laboratory. He reflected on national serv- ice as the sustaining role of the Laboratory Laboratory during the celebrations. We recapture that mood in these pages. since 1942. He termed the Laboratory’s scien- tific achievements as the “gold standard for the country” and lauded the partnership and con- tributions of the University of California. In July 2003, the Board of Regents of the University of California confirmed Nanos as the seventh director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory. “As our country continues to deal with security threats at home and abroad, the work that is being done at this (Left to right) Harold Agnew, John Hopkins, Pete Nanos, Sig Hecker, and John Browne.