Spence's Bend Environmental Water Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NORTH WEST Freight Transport Strategy

NORTH WEST Freight Transport Strategy Department of Infrastructure NORTH WEST FREIGHT TRANSPORT STRATEGY Final Report May 2002 This report has been prepared by the Department of Infrastructure, VicRoads, Mildura Rural City Council, Swan Hill Rural City Council and the North West Municipalities Association to guide planning and development of the freight transport network in the north-west of Victoria. The State Government acknowledges the participation and support of the Councils of the north-west in preparing the strategy and the many stakeholders and individuals who contributed comments and ideas. Department of Infrastructure Strategic Planning Division Level 23, 80 Collins St Melbourne VIC 3000 www.doi.vic.gov.au Final Report North West Freight Transport Strategy Table of Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... i 1. Strategy Outline. ...........................................................................................................................1 1.1 Background .............................................................................................................................1 1.2 Strategy Outcomes.................................................................................................................1 1.3 Planning Horizon.....................................................................................................................1 1.4 Other Investigations ................................................................................................................1 -

Mildura Rural City Council

ELECTORAL STRUCTURE OF MILDURA RURAL CITY COUNCIL LindsayLindsay PointPoint LocalityLocality YeltaYelta LocalityLocality MerbeinMerbein WestWestMerbein LocalityLocality WarganWargan LocalityLocality LocalityLocality BirdwoodtonBirdwoodton LocalityLocality Mildura NedsNeds CornerCorner LocalityLocality MerbeinMerbein SouthSouth CabaritaCabarita NicholsNichols PointPoint LocalityLocality LocalityLocality LocalityLocality LocalityLocality IrympleIrymple SStttuurrrttt HHiiigghhwwaayy SStttuurrrttt HHiiigghhwwaayy CullulleraineCullulleraine KoorlongKoorlong LocalityLocality RedRed CliffsCliffs CardrossCardross RedRed CliffsCliffs LocalityLocality RedRed Cliffs-Cliffs- MeringurMeringur RdRd Meringur Werrimull MerrineeMerrinee LocalityLocality IraakIraakIraak LocalityLocality CarwarpCarwarp LocalityLocality Nangiloc ColignanColignan Mildura Rural City Council Councillors: 9 CalderCalder HighwayHighway HattahHattah LocalityLocality Hattah Murray-SunsetMurray-Sunset LocalityLocality KulwinKulwin LocalityLocality Ouyen Walpeup MittyackMittyack LocalityLocality TutyeTutye LocalityLocality Underbool MalleeMallee HighwayHighway Underbool LingaLinga PanityaPanitya LocalityLocality LocalityLocality TorritaTorrita CowangieCowangie LocalityLocality SunraysiaSunraysia HwyHwy BoinkaBoinka LocalityLocality Murrayville TempyTempy LocalityLocality PatchewollockPatchewollock LocalityLocality LocalityLocality 0 10 20 kilometres BigBig DesertDesert LocalityLocality Legend Locality Boundary Map Symbols Freeway Main Road Collector Road Road Unsealed Road River/Creek -

Mallee Western

Holland Lake Silve r Ci Toupnein ty H Creek RA wy Lake Gol Gol Yelta C a l d e r H Pink Lake w y Merbein Moonlight Lake Ranfurly Mildura Lake Lake Walla Walla RA v A Lake Hawthorn n i k a e MILDURA D AIRPORT ! Kings Millewa o Irymple RA Billabong Wargan KOORLONG - SIMMONS TRACK Lake Channel Cullulleraine +$ Sturt Hwy SUNNYCLIFFS Meringur Cullulleraine - WOORLONG North Cardross Red Cliffs WETLANDS Lakes Karadoc Swamp Werrimull Sturt Hwy Morkalla RA Tarpaulin Bend RA Robinvale HATTAH - DUMOSA TRACK Nowingi Settlement M Rocket u Road RA r ra Lake RA y V a lle y H w HATTAH - RED y OCRE TRACK MURRAY SUNSET Lake - NOWINGI Bitterang Sunset RA LINE TRACK HATTAH - CALDER HIGHWAY EAST Lake Powell Raak Plain RA Lake Mournpall Chalka MURRAY SUNSET Creek RA - ROCKET LAKE TRACK WEST Lake Lockie WANDOWN - NORTH BOUNDARY MURRAY SUNSET Hattah - WILDERNESS PHEENYS TRACK MURRAY SUNSET - Millewa LAST HOPE TRACK MURRAY SUNSET South RA MURRAY SUNSET Kia RA - CALDER ANNUELLO - MURRAY SUNSET - - MENGLER ROAD HIGHWAY WEST NORTH WEST MURRAY SUNSET - +$ LAST HOPE TRACK NORTH EAST BOUNDARY LAST HOPE TRACK MURRAY SUNSET - SOUTH EAST SOUTH EAST LAST HOPE TRACK MURRAY SUNSET SOUTH EAST - TRINITA NORTH BOUNDARY +$ MURRAY SUNSET ANNUELLO - MENGLER MURRAY SUNSET - - EASTERN MURRAY SUNSET ROAD WEST TRINITA NORTH BOUNDARY - WILDERNESS BOUNDARY WEST Berrook RA Mount Crozier RA ANNUELLO - BROKEN GLASS TRACK WEST MURRAY SUNSET - SOUTH MERIDIAN ROAD ANNUELLO - SOUTH WEST C BOUNDARY ANNUELLO - a l d SOUTHERN e r BOUNDARY H w Berrook y MURRAY SUNSET - WYMLET BOUNDARY MURRAY SUNSET -

Fire Operations Plan

Fletchers P o o Lake n c a r i Lake e R Victoria d Da rlin g R iv er d R po m W ru e A n S t ilv w e r o Ci Toupnein r ty t H h w y Creek RA S t M ur ray Riv Yelta er Horse Shoe Lagoon C R a a l n Merbd ein fu e rly r W H ay w y Mildura Lake Walla v A - d Walla RA MERBEIN WEST - a R n g i n th WARGAN BUSHLAND k ro ou a u S e B RESERVE ra MILDURA D u Lake ild AIRPORT M Wallawalla ! Millewa o Irymple RA New Sturt Hwy SUN - CARDROSS Meringur Cullulleraine LAKES EAST South North Red Wales Cliffs Red Cliffs - Colignan Rd ur Rd fs - Mering Red Clif Werrimull S t ur t H w y Morkalla RA Dry Lake Lake Benanee ROB - BUMBANG ISLAND Lake Tarpaulin MS - NORTH Hk Boolca Bend RA Caringay EAST block grasslands Robinvale MS Settlement Rd MS Settlement Rd MURRAY MURRAY SUNSET BOUNDARY Bambill Sth to Merinee Sth Rd Hk Mournpall SUNSET - MERINGUR - BAMBILL Merinee Sth Rd to Meridian Rd Boolga Tracks SETTLEMENT ROAD SOUTH TRACK WEST Nowingi Settlement Rocket HATTAH - RHB Road RA Lake RA M u DUMOSA TRACK r HATTAH - ra y V CALDER a l MINOOK WILDERNESS le HIGHWAY EAST y HKNP - DUMOSA H MURRAY SUNSET - MINERS MURRAY SUNSET w Rocket TRK NORTH y MORKALLA SOUTH TRACK SOUTH NOWINGI LINE y Lake HATTAH - RED a Hattah - r ROAD WEST TRACK EAST r e OCRE TRACK SOUTH Hattah r v Nowingi trk u - Mournpall i north west Lake M R North Sunset RA Cantala Hattah HATTAH - Nowingi Trk Hattah - R MOURNPALL obinvale Rd MS-Shearers West TRACK NORTH Raak MURRAY SUNSET Plain RA HATTAH HATTAH - CANTALA Rd NOWINGI LINE ale MS - BAMBIL BULOKE Chalka inv Hattah - Old TRACK RHB ob SOUTH WEST -

Economic Profile

pull quotes to go agargaefg in this column Mildura Region Economic Profile An analysis of the people, economy and industries of the Mildura region. www.milduraregion.com.auMildura Region Economic Profile 2009 | www.milduraregion.com.au 1 Contents 4 Foreword 23 Employment and Income 23 Labour Force 5 About Us - Employment by Industry and Occupation 27 Income Statistics - Household 6 Local Government Contacts - Individual - Earnings by Industry 7 Overview of the Mildura Region Economy 29 Education 7 Region Definitions 29 Educational Institutions 9 Top 10 Things You Must Know About - La Trobe University (Mildura Campus) the Mildura Region - Sunraysia Institute of TAFE - TAFE NSW - Riverina Institute 33 Qualifications and Education Attainment 11 Regional Economy 34 Enrolment and Field of Study 11 Gross Regional Product (GRP) 13 Businesses by Sector 35 Research and Development in the Mildura Region 15 Population and Demographics - SunRISE 21 Inc. - Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial 15 General Population Research Organisation (CSIRO) - Historic Population - Population Projections 18 Population Profile 37 Environment and Sustainability in - Age Profile the Mildura Region 20 Cultural Diversity - Indigenous Profile 37 Murray Darling Freshwater Research Centre - Country of Birth 37 National Centre For Sustainability - Language Spoken 38 Mallee Sustainable Farming Inc. 21 Housing in the Mildura Region 39 Department of Primary Industries - Victoria - Total Households 39 NSW Department of Primary Industries - Dwelling Structure 40 Department of Sustainability - Housing Tenure & Environment - Victoria 40 Parks Victoria 42 Mallee Catchment Management Authority 42 Lower Murray Darling Catchment Management Authority 2 Mildura Region Economic Profile 2009 | www.milduraregion.com.au Acknowledgements Photography: afoto, Mildura Tourism Inc. and industry sources Design: Visual Strategy Design Published: October 2009 Mapping: SunRISE 21 Inc. -

Acting Principal's Report

Principal: Mr Graeme Cupper Address: Commercial Street, Merbein, 3505 Phone: 03 50252501 Fax: 03 50253524 Email: [email protected] Successful Students – Strong Communities Website: www.merbeinp10.vic.edu.au NEWSLETTER 2018 Thursday, 6 September 201820182018201820182018201820182018201820182 018201820182018201820182018201820182018201820DATES TO REMEMBER 182018201820182018201820182018201820172017201SEPTEMBER ACTING PRINCIPAL’S REPORT 7th Friday 7201720172017 Mrs Sandra Luitjes Yr 2 Sleepover and Excursion 10th Monday Spring has hit, the warmer weather is here and it is the perfect time Pupil Free Day to be out in the garden and planting! 11th Tuesday The Food Technology staff and students have been working on our Yr 10 VicRoads Road Smart incursion ‘Playground to Plate’ Program, which will see new garden beds for 12th Wednesday vegetables and herbs planted next to the Food Technology Room. Whole School Assembly This will allow our students to experience cooking with produce 13th Thursday directly sourced from our own gardens. Congratulations to Bridget -Merbein exchange students travel to China Byrne for being the successful recipient of the grant for this program. -Yr 7 Immunisations 14th Friday PUPIL FREE DAY Yr 4-6 Merbein District Summer Sport Gala Day Next Monday 10th September is a Pupil Free Day. 20th Thursday ‘ASPIRE’ Primary Sports Day There will be no school for students on this day. 21st Friday -Last Day of Term COMPASS PROGRAM -Footy Colours Day If you are having difficulty logging into the school’s -Earlier Finishing time of 2.30pm -OSHC earlier finishing time of 5pm COMPASS Program, please phone the school and OCTOBER talk to Josh, the school’s computer technician 26th Friday during school hours. -

Corrected Version

CORRECTED VERSION RURAL AND REGIONAL COMMITTEE Inquiry into extent and nature of disadvantage and inequity in rural and regional Victoria Mildura — 2 March 2010 Members Ms K. Darveniza Mr R. Northe Mr D. Drum Ms G. Tierney Ms W. Lovell Mr J. Vogels Mr D. Nardella Chair: Mr D. Drum Deputy Chair: Ms G. Tierney Staff Executive Officer: Ms L. Topic Research Officer: Mr P. O’Brien Witnesses Mr M. Hawson, general manager, community and culture, Ms D. Gardner, manager, community development, and Ms L. Barham-Lomax, manager, community care, Mildura Rural City Council. The CHAIR — The Rural and Regional Committee welcomes you to give evidence at our inquiry into the extent and nature of disadvantage and inequity in rural and regional Victoria. All evidence given today is being captured by Hansard and is afforded parliamentary privilege. Before we get started, please give us your names and business addresses and the name of the organisation you are representing, and then we are happy to hear a presentation from you. Mr HAWSON — I am Martin Hawson. I am general manager of community and culture at Mildura Rural City Council and my address is actually this building, which is on the corner of Ninth Street and Deakin Avenue, Mildura. Ms BARHAM-LOMAX — I am Lisa Barham-Lomax. I am the manager of community care services here at Mildura Rural City Council and my address is the same. Ms GARDNER — I am Donna Gardner, the manager of community development at Mildura Rural City Council and my address is the same as Lisa and Martin’s. -

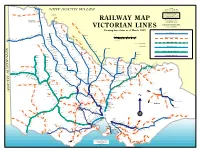

Railway Map Victorian Lines

Yelta Merbein West NOTES Mildura NEW SOUTH WALES All stations are shown with MerbeinIrymple their most recent known names. Redcliffs Abbreviations used Robinvale to Koorakee Morkalla Werrimull Karawinna Yatpool built by VR construction Meringurarrara BG = Broad Gauge (5' 3") Y Pirlta Thurla branch but never handed Benetook over to VR for traffic. Karween Merrinee SG = Standard Gauge (4' 8 1/2") Bambill Carwarp NG = Narrow Gauge (2' 6") Koorakee Boonoonar Benanee RAILWAY MAP Nowingi towards Millewa South Euston All lines shown are or were built by VR construction branch never handed over to VR for traffic, Nowingi Broad Gauge (5' 3") ownership sold to Brunswick Robinvale Plaster Mills 1942 unless otherwise shown. Balranald Bannerton Yangalake No attempt has been made to identify Yungara private railways or tourist lines being Hattah Margooya Impimi Koorkab VICTORIAN LINES run on closed VR lines Annuello Moolpa Kooloonong Trinita Koimbo Perekerten Showing line status as of March 1999 Natya Bolton Kiamal Coonimur Open BG track Kulwin Manangatang Berambong Tiega Piangil Stony Crossing Ouyen MILES Galah Leitpar Moulamein Cocamba Miralie Tueloga Walpeup Nunga 10 5 0 10 20 30 40 Mittyack Dilpurra Linga Underbool Torrita Chinkapook Nyah West Closed or out of use track Boinka Bronzewing Dhuragoon utye 0 5 10 20 30 40 50 60 T Pier Millan Coobool Panitya Chillingollah Pinnaroo Carina Murrayville Cowangie Pira Niemur KILOMETRES Gypsum Woorinen Danyo Nandaly Wetuppa I BG and 1 SG track Swan Hill Jimiringle Tempy Waitchie Wodonga open station Nyarrin Nacurrie Patchewollock Burraboi Speed Gowanford Pental Ninda Ballbank Cudgewa closed station Willa Turriff Ultima Lake Boga Wakool 2 BG and 1 SG track Yarto Sea Lake Tresco Murrabit Gama Deniliquin Boigbeat Mystic Park Yallakool Dattuck Meatian Myall Lascelles Track converted from BG to SG Berriwillock Lake Charm Caldwell Southdown Westby Koondrook Oaklands Burroin Lalbert Hill Plain Woomelang Teal Pt. -

Community Matters ISSUE 36 | August 2018

Community Matters ISSUE 36 | August 2018 Win a $500 voucher! Look inside to find out how Pick up after your pet Picking up after your pet keeps our public spaces clean for everyone to enjoy, and it’s also the law. Read more on page 2. facebook.com/milduracouncil twitter.com/milduracouncil 1 Plenty on for 12-25 year olds Making up around 16 per cent for 12-16 year olds. Activities will run Youth Action Committee will open of our region’s population, from 24 September to 5 October. in November. Stay tuned for more young people play a key role in Enrolments are now open so book details. shaping our community. Council soon to avoid disappointment. is continually working to ensure FReeZA Committee the health and wellbeing of 12 Show Us Your Shorts Help plan and stage live music and to 25 year olds and meet their Film Competition cultural events for young people ever-changing needs. Secondary school aged students are in our region. Applications from invited to get creative and produce 16-25 year olds to join the FReeZA a short film for a chance to share Committee for 2019 will open in Our Youth Engagement Services in great cash prizes. All entries will November. Stay tuned for more team delivers a dynamic range of be shown at a special screening on details. services and programs to young Tuesday 16 October. Entries open 1 people throughout our region. Some September and close on 1 October. great events and opportunities For more information about these coming up include: and other great youth programs call Youth Action Committee our Youth Engagement Services team on 5018 8280, go to September School This 12 month program provides www.mildura.vic.gov.au/youth or Holiday Program opportunities for year 10 students to gain valuable leadership skills check out Youth Services Mildura on Beat the boredom these school and be a voice for the youth of our Facebook or Instagram. -

Metropolitan Convenience, Rural Lifestyle

Metropolitan convenience, rural lifestyle Imagine living nestled on the banks of the Murray River amid irrigated orchards and vineyards with arid red soil and sand dunes as a backdrop. Mildura really is an oasis in our state’s north-west. The regional centre offers residents an enviable lifestyle mix of cosmopolitan vibrancy and country charm in a Mediterranean climate. Housing remains affordable, parking easy and shopping If small-town life is more your style, Mildura Rural City diverse and plentiful, with many of the nation’s major chain Council spans an area of more than 20,000 square stores having outlets across the city. kilometres and includes a dozen warm, friendly and close- knit rural communities such as Merbein, Murrayville, Red The region is home to many award-winning eateries, Cliffs and Ouyen. making the most of fresh, locally-grown produce including wine-grapes, almonds, pistachios, olives, carrots, asparagus and citrus fruit. Ideal location Located on the Murray River in north- west Victoria, Outdoor lovers will revel in the wide array of sports and the Mildura region is 550kms north-west of Melbourne, recreational activities on offer including golf, water-skiing, 400kms north-east of Adelaide and 1080kms west of swimming, lawn bowls, football, shooting and tennis just Sydney. to name a few. Arts and cultural activities are also embraced, with Work-life balance residents given many chances to attend festivals, concerts Spend less time travelling to and from work and more time and productions. embracing sport and recreation, regional festivals, award- winning restaurants, vibrant shopping and delicious fresh produce. -

Chairman's Report

Newsletter of the Murray Valley Citrus Board CITrep • Issue 36 • 2004 inside this issue: Chairman’s Report P1 • Chairman’s Report Robert Mansell, Chairman MVCB P2 • Chief Executive Report • Notes From Neil Eagle The recently released Navel crop forecast Deniliquin: An intensive program of bait, cover indicates a lower than average crop, but higher spray and fruit stripping is underway in Deniliquin, P3 • New Australian Citrus than last year. This season’s fruit looks very clean, in an attempt to reduce the adult population Varieties - Goals and with a minimum amount of rind rub and scurfing. that is taken into winter. Community support Product Specifications The latest fruit measurements show that the for the program has been positive. fruit size of most Navel varieties is larger on P4 • Australian Citrus Growers average by one to one and a half counts. The MVCB is greatly concerned about keeping the 56th Annual Conference Fruit Fly Exclusion Zone (FFEZ) intact. We have The Australian Citrus Growers Annual Conference, met with the NSW Minister for Agriculture, to P5 • Comments on the ACG organised by Sunraysia Citrus Growers, was held stress the importance of agreeing to a Tri State Conference in Mildura last month. It was a very successful Fruit Fly Memorandum of Understanding event and I would like to congratulate SCG on between States. P6 • The Chislett Family their organisation, together with all sponsors, as it wouldn’t have happened without their support. In this context, we believe there is a need to put P8 • Key Points for Winter However, I was disappointed with the number permanent roadblocks in place along the eastern Irrigation of local growers and industry people who did edge of the FFEZ. -

Mildura Rural City Council Submission

Mildura Rural City Council Submission Inquiry into Environmental Infrastructure for Growing Populations SEPTEMBER 2020 The Victorian Legislative Assembly Environment and Planning Committee received the following Terms of Reference from the Legislative Assembly on 1 May 2019: An inquiry into the current and future arrangements to secure environmental infrastructure, particularly parks and open space, for a growing population in Melbourne and across regional centres to the Environment and Planning Committee for consideration. Examples of environmental infrastructure of particular interest to the Committee include parks and open space, sporting fields, forest and bushland, wildlife corridors and waterways. The Committee is primarily interested in environmental infrastructure that is within or close to urbanised areas. Mildura Rural City Council Overview Mildura Rural City (MRCC) is the largest municipality in Victoria, covering an area of 22,330 sq.km. Located in north-west Victoria, it shares borders with New South Wales and South Australia. The population of the local government area is approximately 55,000, dispersed across isolated rural townships, horticulture dependent satellite towns and one central regional city of Mildura township. The township of Mildura is an important regional hub, due to the distance from other regional Cities, Melbourne, and proximity to other states. Mildura Township is located on the Murray River near its junction with the Darling. Mildura has a typical mediterranean climate with dry summers and mild winters. This climate and location make it an ideal place for sport and regional sporting tournaments and events as well as the utilisation of environmental infrastructure such as trails, parks and open space all year round.