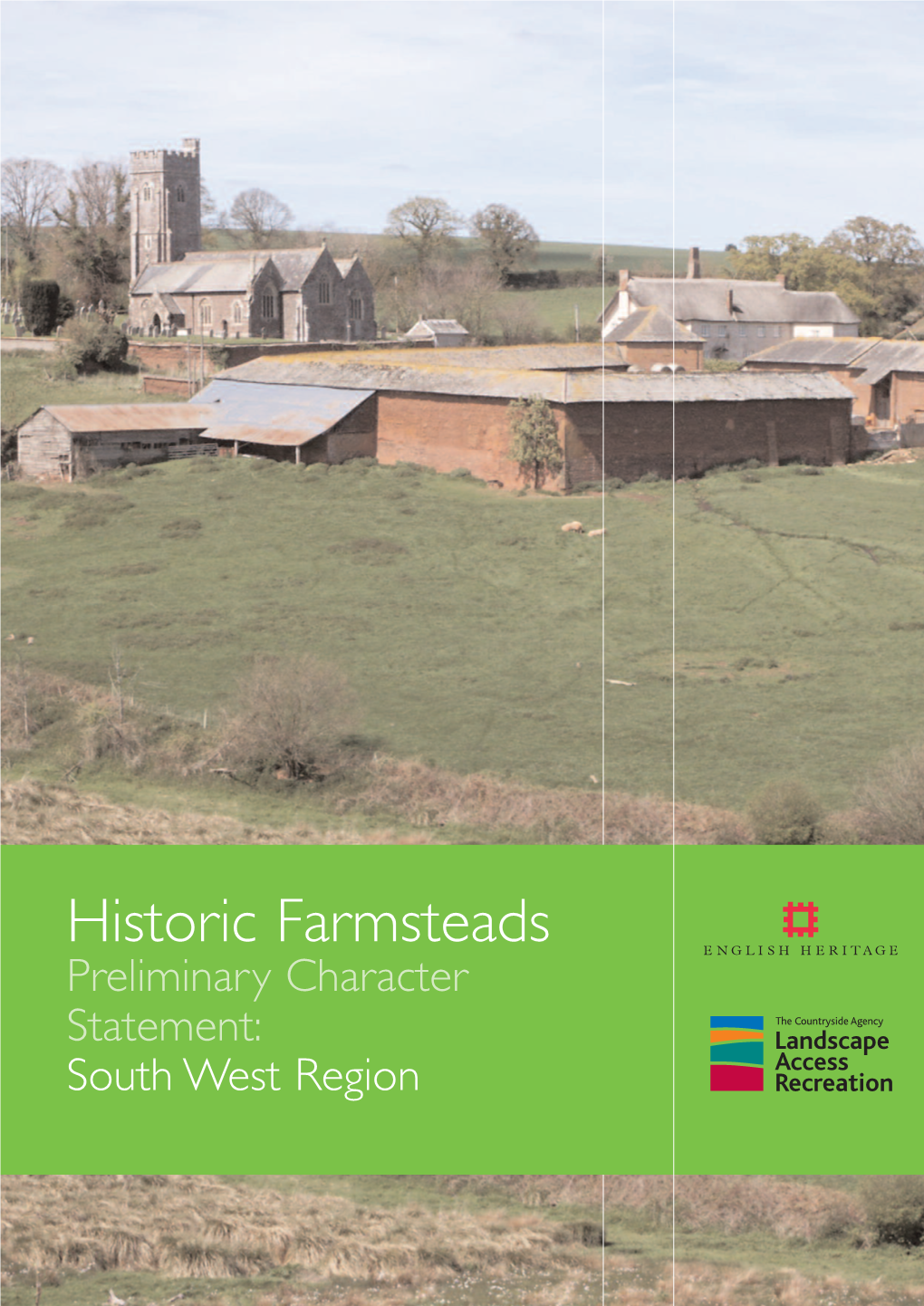

Historic Farmsteads Preliminary Character Statement: South West Region Acknowledgements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Planning Authority Position Statement

FINAL APPROVED 23/12/2013 Cornwall Council and Perranuthnoe Parish Council Recent Housing Proposals 2013 Local Planning Authority Position Statement Perranuthnoe is a rural parish with a population of just over 2300 people. In the last year a number of larger scale housing sites have come forward in locations around a group of settlements in the Parish; namely Goldsithney, Perran Downs and Rosudgeon. The Government has stated a presumption in favour of sustainable development with emphasis on a plan led system supported by up to date evidence. Currently the development plan for the area is at a stage of transition with the former Penwith development plan being outdated and the emerging Cornwall Local Plan yet to be adopted. This transition between plans can cause uncertainty for all involved in the decision making process. Therefore this Local Planning Authority Position Statement presents current housing evidence and collates site specific information into one single document to give certainty and help to manage development in the area. The Position Statement has been compiled and approved by the LPA in close consultation with the local Parish Council and will be a material consideration in the determination of planning applications.1 Evidence of Recent Delivery and Current Housing Need Housing completion data shows a total of 53 affordable homes delivered over 22 years which is equal to an average of 2.4 units each year. During the period 2002 to 2013 a total of 25 affordable homes were provided and the majority of these (23 homes) where at Collygree Parc in 2007. Cornwall HomeChoice Register currently shows 84 households with a local connection to Perranuthnoe Parish. -

Countryside Character Volume 3: Yorkshire & the Humber

Countryside Character Volume 3: Yorkshire & The Humber The character of England’s natural and man-made landscape Contents page Chairman’s Foreword 4 Areas covered by more than one 1 volume are shown Introduction 5 hatched 2 3 The character of England 5 The Countryside Commission and 8 4 countryside character 5 6 How we have defined the character of 8 England’s countryside – The National Mapping project 8 7 – Character of England map: a joint approach 11 8 – Describing the character of England 11 The character of England: shaping the future 11 This is volume 3 of 8 covering the character of England Character Areas page page 21 Yorkshire Dales 13 30 Southern Magnesian Limestone 63 22 Pennine Dales Fringe 20 33 Bowland Fringe and Pendle Hill 69 23 Tees Lowlands 26 34 Bowland Fells 75 24 Vale of Mowbray 32 35 Lancashire Valleys 79 25 North Yorkshire Moors and Cleveland Hills 37 36 Southern Pennines 83 26 Vale of Pickering 43 37 Yorkshire Southern Pennine Fringe 89 27 Yorkshire Wolds 48 38 Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and 28 Vale of York 53 Yorkshire Coalfield 95 29 Howardian Hills 58 39 Humberhead Levels 101 40 Holderness 107 41 Humber Estuary 112 42 Lincolnshire Coast and Marshes 117 43 Lincolnshire Wolds 122 44 Central Lincolnshire Vale 128 45/7 The Lincolnshire Edge with Coversands/ Southern Lincolnshire Edge 133 51 Dark Peak 139 Acknowledgements The Countryside Commission acknowledges the contribution to this publication of a great many individuals, partners and organisations without which it would not have been possible. We also wish to thank Chris Blandford Associates, the lead consultants on this project. -

Horncastle, Fulletby & West Ashby

Lincolnshire Walks Be a responsible walker Walk Information Introduction Please remember the countryside is a place where people live Horncastle, Fulletby Walk Location: Horncastle lies 35km (22 miles) Horncastle is an attractive market town lying at the south-west foot and work and where wildlife makes its home. To protect the of the Lincolnshire Wolds and noted for its antique shops. The east of Lincoln on the A158. Lincolnshire countryside for other visitors please respect it and & West Ashby town is located where the Rivers Bain and Waring meet, and on the on every visit follow the Countryside Code. Thank you. Starting point: The Market Place, Horncastle site of the Roman fort or Bannovallum. LN9 5JQ. Grid reference TF 258 696. • Be safe - plan ahead and follow any signs Horncastle means ‘the Roman town on a horn-shaped piece of land’, • Leave gates and property as you find them Parking: Pay and Display car parks are located at The the Old English ‘Horna’ is a projecting horn-shaped piece of land, • Protect plants and animals, and take litter home Bain (Tesco) and St Lawrence Street, Horncastle. especially one formed in a river bend. • Keep dogs under close control • Consider other people Public Transport: The Interconnect 6 bus service operates This walk follows part of the Viking Way, the long distance footpath between Lincoln and Skegness and stopping in Horncastle. For between the Humber and Rutland Water, to gently ascend into the Most of all enjoy your visit to the further information and times call the Traveline on 0871 2002233 Lincolnshire Wolds Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) and Lincolnshire countryside or visit www.lincolnshire.gov.uk/busrailtravel or the village of Fulletby. -

Dorset Downs and Cranborne Chase

Responding to the impacts of climate change on the natural environment: Natural England publications are available as accessible pdfs from: Dorset Downs and Cranborne Chase www.naturalengland.org.uk/publications Should an alternative format of this publication be required, please contact our enquiries line for more information: A summary 0845 600 3078 or email: [email protected] Printed on Defra Silk comprising 75% recycled fibre. www.naturalengland.org.uk Introduction Natural England is working to deliver Downs and Cranborne Chase. The a natural environment that is healthy, others are the Cumbria High Fells, enjoyed by people and used in a Shropshire Hills, and the Broads. sustainable manner. However, the natural environment is changing as a consequence This leaflet is a summary of the more of human activities, and one of the major detailed findings from the pilot project challenges ahead is climate change. (these are available on our website at www.naturalengland.org.uk). The leaflet: Even the most optimistic predictions show us locked into at least 50 years identifies significant biodiversity, of unstable climate. Changes in landscape, recreational and historic temperature, rainfall, sea levels, and the environment assets; magnitude and frequency of extreme assesses the potential risks climate weather events will have a direct impact change poses to these assets; and on the natural environment. Indirect impacts will also arise as society adapts suggests practical actions that would to climate change. These impacts make them more resilient to the impacts may create both opportunities and of climate change. threats to the natural environment. What we learn from the four pilot Natural England and its partners therefore projects will be used to extend the need to plan ahead to secure the future approach across England as part of of the natural environment. -

Brancepeth APPROVED 2009

Heritage, Landscape and Design Brancepeth APPROVED 2009 1 INTRODUCTION ............................ - 4 - 1.1 CONSERVATION AREAS ...................- 4 - 1.2 WHAT IS A CONSERVATION AREA?...- 4 - 1.3 WHO DESIGNATES CONSERVATION AREAS? - 4 - 1.4 WHAT DOES DESIGNATION MEAN?....- 5 - 1.5 WHAT IS A CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL? - 6 - 1.6 WHAT IS THE DEFINITION OF SPECIAL INTEREST,CHARACTER AND APPEARANCE? - 7 - 1.7 CONSERVATION AREA MANAGEMENT PROPOSALS - 7 - 1.8 WHO WILL USE THE CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL? - 8 - 2 BRANCEPETH CONSERVATION AREA - 8 - 2.1 THE CONTEXT OF THE CONSERVATION AREA - 8 - 2.2 DESIGNATION ...............................- 10 - 2.3 DESCRIPTION OF THE AREA............- 10 - 2.4 SCHEDULE OF THE AREA ...............- 10 - 2.5 HISTORY OF THE AREA ..................- 12 - 3 CHARACTER ZONES .................. - 14 - 3.1 GENERAL .....................................- 14 - 3.2 ZONES A AND B............................- 15 - 3.3 ZONE C........................................- 16 - 3.4 ZONE D........................................- 17 - 3.5 ZONE E ........................................- 18 - 3.6 ZONES F, G AND H........................- 20 - 4 TOWNSCAPE AND LANDSCAPE ANALYSIS - 21 - 4.1 DISTINCTIVE CHARACTER...............- 21 - 4.2 ARCHAEOLOGY.............................- 22 - 4.3 PRINCIPAL LAND USE ...................- 22 - 4.4 PLAN FORM..................................- 22 - 4.5 VIEWS INTO, WITHIN AND OUT OF THE CONSERVATION AREA - 23 - 4.6 STREET PATTERNS AND SCENES ....- 24 - 4.7 PEDESTRIAN ROUTES ....................- -

Pendeen Conservation Area Appraisal

Pendeen Conservation Area Appraisal DRAFT AUGUST 2009 Contents: Page Conservation Area Map Summary of Special Interest 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Conservation Areas 2 1.2 Pendeen's Conservation Area 2 1.3 Purpose & Scope of this Character Appraisal 2 1.4 Planning Policy Framework 3 1.5 World Heritage Site Inscription 3 1.6 Consultation and Adoption 4 2.0 LOCATION & LANDSCAPE SETTING 2.1 Location 5 2.2 Landscape Setting 5 3.0 HISTORY & DEVELOPMENT 3.1 The History of Pendeen 7 3.2 Physical Development 10 Pre-Industrial 10 Industrial (1820 - 1986) 11 Post Industrial 12 3.3 c1880 OS Map 3.4 c1907 OS Map 4.0 APPRAISAL OF SPECIAL INTEREST 4.1 General Character 13 4.2 Surviving Historic Fabric 15 Pre-Industrial 15 Industrial 15 4.3 Architecture, Geology & Building Materials 18 Architectural Styles 18 Geology & Building Materials 21 4.4 Streetscape 23 4.5 Spaces, Views & Vistas 25 4.6 Character Areas 26 ¾ Crescent Place/North Row/The Square 26 ¾ North Row/The Square 28 ¾ The Church & School Complex 30 ¾ Higher Boscaswell/St John's Terrace 32 • Boscaswell United Mine 35 • St John's Terrace 37 ¾ Boscaswell Terrace/Carn View Terrace 39 • The Radjel Inn/Old Chapel 29 • Boscasweel Terrace 40 • Carn View Terrace 41 Calartha Terrace/Portheras Cross 42 5.0 PRESERVATION AND ENHANCEMENT 5.1 Preservation 44 5.2 Design Guidance 45 5.3 Listed Buildings & Scheduled Ancient Monuments 46 5.4 The Protection of Other Buildings 47 5.5 Issues 48 5.5.1 Highway Related Issues 48 5.5.2 Boundary Treatment and Garden Development 50 5.5.3 Outbuildings 51 5.5.4 Retaining References -

North and Mid Somerset CFMP

` Parrett Catchment Flood Management Plan Consultation Draft (v5) (March 2008) We are the Environment Agency. It’s our job to look after your environment and make it a better place – for you, and for future generations. Your environment is the air you breathe, the water you drink and the ground you walk on. Working with business, Government and society as a whole, we are making your environment cleaner and healthier. The Environment Agency. Out there, making your environment a better place. Published by: Environment Agency Rio House Waterside Drive, Aztec West Almondsbury, Bristol BS32 4UD Tel: 01454 624400 Fax: 01454 624409 © Environment Agency March 2008 All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior permission of the Environment Agency. Environment Agency Parrett Catchment Flood Management Plan – Consultation Draft (Mar 2008) Document issue history ISSUE BOX Issue date Version Status Revisions Originated Checked Approved Issued to by by by 15 Nov 07 1 Draft JM/JK/JT JM KT/RR 13 Dec 07 2 Draft v2 Response to JM/JK/JT JM/KT KT/RR Regional QRP 4 Feb 08 3 Draft v3 Action Plan JM/JK/JT JM KT/RR & Other Revisions 12 Feb 08 4 Draft v4 Minor JM JM KT/RR Revisions 20 Mar 08 5 Draft v5 Minor JM/JK/JT JM/KT Public consultation Revisions Consultation Contact details The Parrett CFMP will be reviewed within the next 5 to 6 years. Any comments collated during this period will be considered at the time of review. Any comments should be addressed to: Ken Tatem Regional strategic and Development Planning Environment Agency Rivers House East Quay Bridgwater Somerset TA6 4YS or send an email to: [email protected] Environment Agency Parrett Catchment Flood Management Plan – Consultation Draft (Mar 2008) Foreword Parrett DRAFT Catchment Flood Management Plan I am pleased to introduce the draft Parrett Catchment Flood Management Plan (CFMP). -

Peripheral Landscape Study – Ilchester

Peripheral landscape study – Ilchester Conservation and Design Unit South Somerset District Council February 2010 Peripheral landscape study - Ilchester Page No: Contents – 1. Background to study 3 2. The settlement 4 3. Landscape character 5 4. Landscape sensitivity 9 5. Visual sensitivity 12 6. Values and Constraints 16 7. Landscape capacity 17 8. Proposals 19 9. Appendices 21 (1) - capacity matrix (2) - historic landscape character (3) - photos (1-14) 10. Plans - 1) site context and study area - 2) landscape character sensitivity - 3) visual sensitivity - 4) values and constraints - 5) landscape capacity Page 2 of 22 Peripheral landscape study - Ilchester 1) Background to the study: 1.1. The forthcoming South Somerset Local Development Framework (LDF) will be required to allocate new development sites for both housing and employment for the period 2006-2026, with the focus of major growth placed upon Yeovil, thereafter the district’s major towns and rural centres. As part of the process of finding suitable sites for development, a landscape study to assess the capacity of the settlement fringe to accommodate new development in a landscape-sympathetic manner, is commissioned. This will complement other evidence-based work that will contribute to the LDF process. 1.2 PPS 7 commends the approach to the identification of countryside character developed by the Countryside Agency (now Natural England) and suggests that it can assist in accommodating necessary change due to development without sacrifice of local character and distinctiveness. -

Yeovil Scarplands Sweep in an Arc from the Mendip Hills Around the Southern Edge of Somerset Levels and Moors to the Edge of the Blackdowns

Character Area Yeovil 140 Scarplands Key Characteristics Much of the higher ground has sparse hedge and tree cover with an open, ridgetop, almost downland, character. In ● A very varied landscape of hills, wide valley bottoms, some areas, the high ground is open grassland falling away ridgetops and combes united by scarps of Jurassic steeply down intricately folded slopes. There are limestone. spectacular views across the lowland landscape framed by sheltered golden-stoned villages like Batcombe. In other ● Mainly a remote rural area with villages and high church towers. areas of high ground, there is more arable and the ridges are broader. The steep slopes below these open ridge tops ● Wide variety of local building materials including are in pasture use and are cut by narrow, deep valleys predominantly Ham Hill Stone. ('goyles') often with abundant bracken and scrub. Within ● Small manor houses and large mansions with the valleys there is a strong character of enclosure landscape parks. and remoteness. ● Varied land use: arable on the better low-lying land, woodland on the steep ridges and deep combes. Landscape Character The Yeovil Scarplands sweep in an arc from the Mendip Hills around the southern edge of Somerset Levels and Moors to the edge of the Blackdowns. Rivers like the Brue, Parrett and Yeo drain from the higher ground of the Scarplands cutting an intricate pattern of irregular hills and valleys which open out to the moorland basins. To the east there is a gradual transition to Blackmore Vale and the Vale JULIAN COMRIE/COUNTRYSIDE AGENCY JULIAN COMRIE/COUNTRYSIDE of Wardour and the area is separated from Marshwood Vale The Yeovil Scarplands comprise several scarps and vales formed by the ridge above the Axe Valley. -

Dorset and East Devon Coast for Inclusion in the World Heritage List

Nomination of the Dorset and East Devon Coast for inclusion in the World Heritage List © Dorset County Council 2000 Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum June 2000 Published by Dorset County Council on behalf of Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum. Publication of this nomination has been supported by English Nature and the Countryside Agency, and has been advised by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee and the British Geological Survey. Maps reproduced from Ordnance Survey maps with the permission of the Controller of HMSO. © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Licence Number: LA 076 570. Maps and diagrams reproduced/derived from British Geological Survey material with the permission of the British Geological Survey. © NERC. All rights reserved. Permit Number: IPR/4-2. Design and production by Sillson Communications +44 (0)1929 552233. Cover: Duria antiquior (A more ancient Dorset) by Henry De la Beche, c. 1830. The first published reconstruction of a past environment, based on the Lower Jurassic rocks and fossils of the Dorset and East Devon Coast. © Dorset County Council 2000 In April 1999 the Government announced that the Dorset and East Devon Coast would be one of the twenty-five cultural and natural sites to be included on the United Kingdom’s new Tentative List of sites for future nomination for World Heritage status. Eighteen sites from the United Kingdom and its Overseas Territories have already been inscribed on the World Heritage List, although only two other natural sites within the UK, St Kilda and the Giant’s Causeway, have been granted this status to date. -

Stainsby House Farm (549 Acres) Ashby Puerorum, Lincolnshire

Stainsby House Farm (549 acres) Ashby Puerorum, Lincolnshire Stainsby House Farm Ashby Puerorum Stainsby House Farm is a versatile well equipped residential farm extending to 549 acres situated in and with commanding views of ‘Tennyson Country’ in the Lincolnshire Wolds, an ‘Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty’. Stainsby House Farm is a productive arable farm with central residence, modern and traditional farm buildings, and two cottages. The farm lies close to the hamlet of Ashby Puerorum approximately 2.5 miles south of the village of Tetford and 6 miles East of the market town of Horncastle. The Lincolnshire Wolds is well known for its tranquil nature and rich agricultural heritage and the rolling hills have excellent walking, cycling and riding routes. The area has numerous Golf Courses including the home of the English Golf Union at Woodhall Spa. Horse racing can be found at Market Rasen and Motor Sports at Cadwell Park. The Wolds are well known for their game shooting and are home to the South Wold and Brocklesby Hounds. The market towns provide the services required and retain much of their historic character. All of the nearby market towns benefit from good grammar schools and independent schools in the region include Lincoln Minister, Oakham, Oundle, Stamford, Uppingham and Worksop. Mainline rail services are situated at Lincoln (28 miles), Newark (45miles), and Grantham (43miles) and nearby airports are Humberside (36miles), Robin Hood Doncaster (57miles) and East Midlands (78miles). Stainsby House Stainsby House, standing high up in a perfectly sheltered Wolds setting of trees, is situated in the middle of the ring-fenced farm. -

Farm Buildings Design Guide Harrogate Borough Council – Farm Buildings Design Guide

Harrogate Borough Council Farm Buildings Design Guide Harrogate Borough Council – Farm Buildings Design Guide Farm Buildings Design Guide CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Page 2 SECTION 1 – NEW FARM BUILDINGS Page 5 SECTION 2 – CONVERSION AND ALTERATION OF Page 22 TRADITIONAL FARM BUILDINGS SECTION 3 – PLANNING REQUIREMENTS Page 29 APPENDICES – LANDSCAPE AND FARMSTEAD Page 34 CHARACTERFarm Buildings OVERVIEWS Design Guide Appendix 1 – Area 1 Uplands and Moorland Fringes INTRODUCTION Appendix 2 – Area 2 Magnesian Limestone Ridge and Eastern Fringe (Lowlands) Date of Guidance: Version 1 - 10th December 2020 Page 1 of 44 Harrogate Borough Council – Farm Buildings Design Guide Farm Buildings Design Guide INTRODUCTION The countryside within Harrogate District contains a variety of landscapes, stretching from the Dales in the west to the Vale of York in the east. The character of these landscapes derives from human influences as much as from physical characteristics. Traditional farmsteads and field barns make a major contribution to this valued landscape character with local building materials and methods of construction relating to the geology and historic development of each area. Traditional farmsteads set within the landscape of the west of the Harrogate District Why is the guidance needed? The changes that we make to the landscape can potentially be harmful, be it through the introduction of a new farm building or the conversion of traditional farm buildings. Changes are partly required because farming practices have evolved over the 20th century: . Since the 1940s, farms have increasingly favoured large, standard specification multi- purpose “sheds” - typically steel frame portal in design - to accommodate increasingly mechanised operations, higher animal welfare standards and greater storage requirements.