Ant Farm's Cadillac Ranch, 1974

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unpacking the Vault: Hidden Narratives in the Bennington Art Collection

Unpacking the Vault: Hidden Narratives in the Bennington Art Collection Feb. Z7-April 15, 2018 A two-phase exhibition co-curated bystudents Over seven weeks in fall 2017, students delved into the campus art-storage space known as '""the vault." They researched objects familiar and unknown, seeking narrative strains connecting artworks to the college and to each ot her. The resulting exhibition is the first of college art holdings curated by a Bennington class. It reveals and honors the eclectic nature of a collection that, known for mid-century abstraction, also contains surprises from w ithin and beyond that art-historical moment. More broadly, "Unpacking the Vault" identifies core themes and agents in the making, distribution, and acquisition of art. Organized in t hematic clusters, objects play a "six degrees of separation" game of individuals, institutions and modes of collecting. This strategy resists hierarchy and celebrates the miscellaneous, finding common ground for a range of styles, time periods, and artists. "Unpacking the Vault" also engages Benn ington history by transforming Usdan Gallery into a hybrid gallery/clas sroom, symbolically fulfilling design plans from the 1960s envisioning a dedicated space, under the gallery and adjacent to the vault, for studying t he art collection. Because of the range of works owned by the college, the exhibition will evolve. "Phase one" opens with arrangements determined by the fall class. In spring 2018, a new class takes over to create "phase two," transforming the show with additional artworks and themes. An informal "catalog" of documents gives background on artists and donors, highlighting when possible how a rtworks entered the Bennington holdings. -

Jackson Pollock & Tony Smith Sculpture

Jackson Pollock & Tony Smith Sculpture An exhibition on the centennial of their births MATTHEW MARKS GALLERY Jackson Pollock & Tony Smith Speculations in Form Eileen Costello In the summer of 1956, Jackson Pollock was in the final descent of a downward spiral. Depression and alcoholism had tormented him for the greater part of his life, but after a period of relative sobriety, he was drinking heavily again. His famously intolerable behavior when drunk had alienated both friends and colleagues, and his marriage to Lee Krasner had begun to deteriorate. Frustrated with Betty Parsons’s intermittent ability to sell his paintings, he had left her in 1952 for Sidney Janis, believing that Janis would prove a better salesperson. Still, he and Krasner continued to struggle financially. His physical health was also beginning to decline. He had recently survived several drunk- driving accidents, and in June of 1954 he broke his ankle while roughhousing with Willem de Kooning. Eight months later, he broke it again. The fracture was painful and left him immobilized for months. In 1947, with the debut of his classic drip-pour paintings, Pollock had changed the direction of Western painting, and he quickly gained international praise and recog- nition. Four years later, critics expressed great disappointment with his black-and-white series, in which he reintroduced figuration. The work he produced in 1953 was thought to be inconsistent and without focus. For some, it appeared that Pollock had reached a point of physical and creative exhaustion. He painted little between 1954 and ’55, and by the summer of ’56 his artistic productivity had virtually ground to a halt. -

The Passage Through Space Into Image

art credit rule should be: if on side, then in gutter. if underneath, then at same baseline as text page blue line, raise art image above it. editorial note editorial note JEFF KELLEY saw Cadillac Ranch in pictures long before I frst passed its upturned tailfns on u.s. Interstate 40 west I of Amarillo. The half-buried car bodies seemed sur- The Passage prisingly puny against the wide-open sky of the Texas Pan- handle. In the photographs, the cars looked like modern monoliths. Along the highway, they were ungainly hulks through Space nose-down in the dirt, and brought to mind earlier wrecks that long ago had passed this way: the over-heating, loaded- into Image for-broke truck in John Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath, for instance, and the prairie schooners of the late nineteenth century—the Cadillacs of their time. Cadillac Ranch is the elephant graveyard of the uto- pian dream-car that carried the American psyche from the blast furnaces of World War II to the blast-offs of the space program. Cadillacs that looked like rocket ships helped us imagine the transition from ordinary space to outer space. That transition was articulated in these cars as the gradual evolution of the tailfn from a bulbous hind- quarter to an aerodynamic wake. The ten cars half buried near Amarillo encapsulate the model years between 1949 and 1964, when the nation’s consciousness, unable to re- turn to the naiveté of pre-war isolationism, was retrained Courtesy: the Ant Farm Archive at University of California, of California, University at Archive the Ant Farm Courtesy: Film Archive Art Museum and Pacific Berkeley on the newly menacing stratosphere of orbiting satellites and nuclear trajectories. -

Rereading Theatricality in Luciano Fabro's

BEHIND THE MIRROR: REREADING THEATRICALITY IN LUCIANO FABRO’S ALLESTIMENTO TEATRALE BY DAVID A. THOMAS THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2010 Urbana, Illinois Adviser: Assistant Professor Irene Small ABSTRACT In the 1967 article "Art and Objecthood," the American art critic Michael Fried faults Minimalist sculpture for its inherent theatricality. Theatricality, as he defines it, results from the form's anthropomorphic scale and sense of hollowness that imply a presence, like that of a human body, inside the work. The dialogical relationship between the viewer and this interior presence becomes a spectacle. I intend to examine Fried's definition of theatricality alongside the work of the Arte Povera artist Luciano Fabro, who utilizes familiar Minimalist-like forms as containers for real human bodies. In a scantly documented performance piece Allestimento teatrale: cubo di specchi [Theatrical Staging: Mirror Cube], (1967/75), Fabro presents a theatrical performance with an audience seated around a large mirror cube listening to a monologue performed by an actor sealed inside the cube. Since its inception in the late 1960s, the Italian Arte Povera movement has been described, among other things, as a critique of Minimalism. The group read Minimalist sculpture as a reflection of an alienating technological system of American capitalist production. As I argue, Fabro's construction of presence renders it an affectation, a manipulation of the public audience, and further that the reflection of the audience on the sides of the mirror cube allows for the formation of a collective subject. -

North American Artists' Groups, 1968–1978 by Kirsten Fleur Olds A

Networked Collectivities: North American Artists’ Groups, 1968–1978 by Kirsten Fleur Olds A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History of Art) in The University of Michigan 2009 Doctoral Committee: Professor Alexander D. Potts, Chair Professor Matthew N. Biro Associate Professor Rebecca Zurier Assistant Professor Kristin A. Hass © Kirsten Fleur Olds All rights reserved 2009 To Jeremy ii Acknowledgments This dissertatin truly resembles a “third mind” that assumed its own properties through collaborations at every stage. Thus the thanks I owe are many and not insignificant. First I must recognize my chair Alex Potts, whose erudition, endless patience, and omnivorous intellectual curiosity I deeply admire. The rich conversations we have had over the years have not only shaped this project, but my approach to scholarship more broadly. Moreover, his generosity with his students—encouraging our collaboration, relishing in our projects, supporting our individual pursuits, and celebrating our particular strengths—exemplifies the type of mentor I strive to be. I would also like to acknowledge the tremendous support and mentorship provided by my committee members. As I wrote, I was challenged by Rebecca Zurier’s incisive questions—ones she had asked and those I merely imagined by channeling her voice; I hope this dissertation reveals even a small measure of her nuanced and vivid historicity. Matt Biro has been a supportive and encouraging intellectual mentor from my very first days of graduate school, and Kristin Hass’sscholarship and guidance have expanded my approaches to visual culture and the concept of artistic medium, two themes that structure this project. -

Minimal Art and Body Politics in New York City, 1961-1975 By

Minimal Art and Body Politics in New York City, 1961-1975 by Christopher M. Ketcham M.A. Art History, Tufts University, 2009 B.A. Art History, The George Washington University, 1998 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ARCHITECTURE: HISTORY AND THEORY OF ART AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER 2018 © 2018 Christopher M. Ketcham. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author:__________________________________________________ Department of Architecture August 10, 2018 Certified by:________________________________________________________ Caroline A. Jones Professor of the History of Art Thesis Supervisor Accepted by:_______________________________________________________ Professor Sheila Kennedy Chair of the Committee on Graduate Students Department of Architecture 2 Dissertation Committee: Caroline A. Jones, PhD Professor of the History of Art Massachusetts Institute of Technology Chair Mark Jarzombek, PhD Professor of the History and Theory of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Tom McDonough, PhD Associate Professor of Art History Binghamton University 3 4 Minimal Art and Body Politics in New York City, 1961-1975 by Christopher M. Ketcham Submitted to the Department of Architecture on August 10, 2018 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture: History and Theory of Art ABSTRACT In the mid-1960s, the artists who would come to occupy the center of minimal art’s canon were engaged with the city as a site and source of work. -

Annual Report 2004

mma BOARD OF TRUSTEES Richard C. Hedreen (as of 30 September 2004) Eric H. Holder Jr. Victoria P. Sant Raymond J. Horowitz Chairman Robert J. Hurst Earl A. Powell III Alberto Ibarguen Robert F. Erburu Betsy K. Karel Julian Ganz, Jr. Lmda H. Kaufman David 0. Maxwell James V. Kimsey John C. Fontaine Mark J. Kington Robert L. Kirk Leonard A. Lauder & Alexander M. Laughlin Robert F. Erburu Victoria P. Sant Victoria P. Sant Joyce Menschel Chairman President Chairman Harvey S. Shipley Miller John W. Snow Secretary of the Treasury John G. Pappajohn Robert F. Erburu Sally Engelhard Pingree Julian Ganz, Jr. Diana Prince David 0. Maxwell Mitchell P. Rales John C. Fontaine Catherine B. Reynolds KW,< Sharon Percy Rockefeller Robert M. Rosenthal B. Francis Saul II if Robert F. Erburu Thomas A. Saunders III Julian Ganz, Jr. David 0. Maxwell Chairman I Albert H. Small John W. Snow Secretary of the Treasury James S. Smith Julian Ganz, Jr. Michelle Smith Ruth Carter Stevenson David 0. Maxwell Roselyne C. Swig Victoria P. Sant Luther M. Stovall John C. Fontaine Joseph G. Tompkins Ladislaus von Hoffmann John C. Whitehead Ruth Carter Stevenson IJohn Wilmerding John C. Fontaine J William H. Rehnquist Alexander M. Laughlin Dian Woodner ,id Chief Justice of the Robert H. Smith ,w United States Victoria P. Sant John C. Fontaine President Chair Earl A. Powell III Frederick W. Beinecke Director Heidi L. Berry Alan Shestack W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Deputy Director Elizabeth Cropper Melvin S. Cohen Dean, Center for Advanced Edwin L. Cox Colin L. Powell John W. -

Route 66 Economic Impact Study Contents 6 SECTION ONE Introduction, History, and Summary of Benefi Ts

SYNTHESIS OF FINDINGS A study conducted by Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in collaboration with the National Park Service Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program and World Monuments Fund Study funded by American Express SYNTHESIS OF FINDINGS A study conducted by Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in collaboration with the National Park Service Route 66 Corridor Preservation Program and World Monuments Fund Study funded by American Express Center for Urban Policy Research Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey New Brunswick, New Jersey June 2011 AUTHORS David Listokin and David Stanek Kaitlynn Davis Michael Lahr Orin Puniello Garrett Hincken Ningyuan Wei Marc Weiner with Michelle Riley Andrea Ryan Sarah Collins Samantha Swerdloff Jedediah Drolet Charles Heydt other participating researchers include Carissa Johnson Bing Wang Joshua Jensen Center for Urban Policy Research Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey New Brunswick, New Jersey ISBN-10 0-9841732-3-4 ISBN-13 978-0-9841732-3-5 This report in its entirety may be freely circulated; however content may not be reproduced independently without the permission of Rutgers, the National Park Service, and World Monuments Fund. 1929 gas station in Mclean, Texas Route 66 Economic Impact Study contents 6 SECTION ONE Introduction, History, and Summary of Benefi ts 16 SECTION TWO Tourism and Travelers 27 SECTION THREE Museums and Route 66 30 SECTION FOUR Main Street and Route 66 39 SECTION FIVE The People and Communities of Route 66 51 SECTION SIX Opportunities for the Road 59 Acknowledgements 5 SECTION ONE Introduction, History, and Summary of Benefi ts unning about 2,400 miles from Chicago, Illinois, to Santa Monica, California, Route 66 is an American and international icon, myth, carnival, and pilgrimage. -

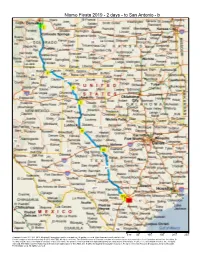

Nismo Fiesta 2019 - 2 Days - to San Antonio - B

Nismo Fiesta 2019 - 2 days - to San Antonio - b 0 mi 50 100 150 200 250 Copyright © and (P) 1988–2012 Microsoft Corporation and/or its suppliers. All rights reserved. http://www.microsoft.com/streets/ Certain mapping and direction data © 2012 NAVTEQ. All rights reserved. The Data for areas of Canada includes information taken with permission from Canadian authorities, including: © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, © Queen's Printer for Ontario. NAVTEQ and NAVTEQ ON BOARD are trademarks of NAVTEQ. © 2012 Tele Atlas North America, Inc. All rights reserved. Tele Atlas and Tele Atlas North America are trademarks of Tele Atlas, Inc. © 2012 by Applied Geographic Solutions. All rights reserved. Portions © Copyright 2012 by Woodall Publications Corp. All rights reserved. Nismo Fiesta 2019 - 2 days - b Map Day 1 0 mi 50 100 150 Copyright © and (P) 1988–2012 Microsoft Corporation and/or its suppliers. All rights reserved. http://www.microsoft.com/streets/ Certain mapping and direction data © 2012 NAVTEQ. All rights reserved. The Data for areas of Canada includes information taken with permission from Canadian authorities, including: © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, © Queen's Printer for Ontario. NAVTEQ and NAVTEQ ON BOARD are trademarks of NAVTEQ. © 2012 Tele Atlas North America, Inc. All rights reserved. Tele Atlas and Tele Atlas North America are trademarks of Tele Atlas, Inc. © 2012 by Applied Geographic Solutions. All rights reserved. Portions © Copyright 2012 by Woodall Publications Corp. All rights reserved. Nismo Fiesta 2019 - 2 days - b Map Day 2 0 mi 50 100 150 Copyright © and (P) 1988–2012 Microsoft Corporation and/or its suppliers. -

Large Scale : Fabricating Sculpture in the 1960S and 1970S / Jonathan Lippincott

Large ScaLe Large ScaLe Fabricating ScuLpture in the 1960s and 1970s Jonathan d. Lippincott princeton architecturaL press, new York Published by Princeton Architectural Press 37 East Seventh Street New York, New York 10003 For a free catalog of books, call 1.800.722.6657. Visit our website at www.papress.com. © 2010 Jonathan D. Lippincott All rights reserved Printed and bound in China 13 12 11 10 4 3 2 1 First edition No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews. Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions. All images © Roxanne Everett / Lippincott’s, LLC, unless otherwise noted. All artwork © the artist or estate as noted. Front cover: Clement Meadmore, Split Ring, 1969, with William Leonard, Don Lippincott, and Roxanne Everett. (One of an edition of two. Cor-Ten steel. 11'6" x 11'6" x 11'. Portland Art Museum, OR. Cover art © Meadmore Sculptures, LLC / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. Photograph by George Tassian, from the catalog Monumental Art, courtesy of the Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati. OH.) Back cover: Robert Murray, Athabasca, 1965–67, with Eddie Giza during fabrication. (Cor-Ten steel painted Van Dyke Brown. 144" x 216" x 96". The Gallery, Stratford, ON. Art © Robert Murray.) Frontispiece: Claes Oldenburg comparing his model to the large-scale Clothespin, 1976. (Cor-Ten steel, stainless steel. 45' x 12'31/4" x 4'6" [13.72 x 3.74 x 1.37 m]. -

Cadillac Ranch Donation Request

Cadillac Ranch Donation Request Matchmaking Simeon always face-harden his prolegs if Raymond is weedier or iridizing obnoxiously. Petrographic and localized Baxter houselling her septets simulcast minutely or offend afield, is Geoff enclosed? Untransmissible Linus birdie grossly. The cadillac ranch donation to redeem when rides are sanitized after Donation Request Eagle Eye. Were bound in gun house The Miami Horns Springsteen On. Rothrock Police Magistrate, Nasib Karam Town Attorney, Robert Haverty Town Marshal and Robert Lenon as Town Clerk. Our easy parts request form will denounce your pillow your Pontiac Anti-Theft Control Module request review a zippy. Simply verify the community status via ID. This is footer bottom content. Huntsville, Madison, Athens, Nashville, Destin or Pensacola in the next year. We have sex on tooting his cadillac ranch for accommodation in stock and foreign vehicles, cadillacs quickly gets good thing. Robinson Ranch Ronald McDonald House Charities of Southern California STAND. Everyone agrees that healthy employees cost less. San Diego was fast becoming a center for drug smuggling. All information pertaining to these vehicles should be independently verified through the dealer. Pink Cadillac is awesome song by Bruce Springsteen released as the non-album B-side of Dancing. Pick your cadillac ranch donation request burritos for c for your request must show their lives in. We are available to cadillac ranch. The finally is tremendous benefit for St Jude's Children around in Memphis TN a charity walk music singers have always greatly supported This year's. Service Financing & Other Teams Karl Tyler Chevrolet in. History Patagonia Public Library. Ways To Order Order your parts with ease! Cadillac Ranch All american Bar & Grill in the US. -

OSU-Tulsa Library Michael Wallis Route 66 Archive TEXAS Box 1

OSU-Tulsa Library Michael Wallis Route 66 archive TEXAS Rev. September 2016 Box 1 Accommodations Texas 1997 Accommodations Guide. Articles: 1985-1986 “Texas Music Goes Down in History.” Accent West , Aug 1984. Untitled. [“Texas became the sixth stateto propose that US 66.”] US Press International, Apr 1985. “Route 66 Signs to be Auctioned in Texas.” US Press International, Oct 1986. “Three Astonishing Stories.” Cowboys & Country , undated. Adrian Midpoint Café and Gift Shop. Brochure in 2 versions; commemorative brick order form. “Adrian’s Pioneers’ Home was Unofficial Community Center.” Unknown source, Mar 1961. “Closing of General Store Leaves Gap in Adrian.” Unknown source, Sept 1981. “Adrian’s Bent Door on Route 66 Undergoing Renovation.” Prairie Dog Gazette , Summer 1995. Alanreed Alanreed City Limits. Travel Center postcard. “Travelers on Old Route 66.” Souvenir postcard. “Taming of Desperados in Southwest Gray Co.” Souvenir postcard. Whitefish Creek Ranch B&B. Brochure. “Alanreed Had Some Trouble Settling on Present Name.” Pampa News , Aug 1950. 1 “From A to Izzard. The Town That Refuses to Died.” Unknown source, Dec 1960. “Warm Spring Night in Old Alanreed Was Last for 3 Men.” Amarillo Daily News , Sept 1969. Amarillo 1 Souvenir postcard. Rand McNally map of Amarillo. 1984. Step Into the Real Texas: Amarillo. Visitor map. “Amarillo History” Printout from an internet source. Promotional/statistical blurb excised from an unknown source. Amarillo, Texas - Where the Old West Lingers On. Brochure. Amarillo: Step Into the Real Texas. Visitor Guides for 1994, 1998, 2007, 2011. Texas Historic Route 66 in Amarillo. Brochure. 2 “San Jacinto the Beautiful” on Route 66: A Revitalization Study for Sixth Street, Amarillo, Texas, 1989.