Middlesbrough: Just Another Brick in the Red Wall?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

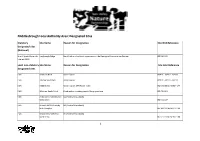

ORTHODONTIC COMMISSIONING INTENTIONS (Final - Sept 2018)

CUMBRIA & NORTH EAST - ORTHODONTIC COMMISSIONING INTENTIONS (Final - Sept 2018) Contract size Contract Size Units of Indicative Name of Contract Lot Required premise(s) locaton for contract Orthodontic Activity patient (UOAs) numbers Durham Central Accessible location(s) within Central Durham (ie Neville's Cross/Elvet/Gilesgate) 14,100 627 Durham North West Accessible location(s) within North West Durham (ie Stanley/Tanfield/Consett North) 8,000 356 Bishop Auckland Accessible location(s) within Bishop Auckland 10,000 444 Darlington Accessible location(s) within the Borough of Darlington 9,000 400 Hartlepool Accessible location(s) within the Borough of Hartlepool 8,500 378 Middlesbrough Accessible location(s) within the Borough of Middlesbrough 10,700 476 Redcar and Cleveland Accessible location(s) within the Borough of Redcar & Cleveland, (ie wards of Dormanstown, West Dyke, Longbeck or 9,600 427 St Germains) Stockton-on-Tees Accessible location(s) within the Borough of Stockton on Tees) 16,300 724 Gateshead Accessible location(s) within the Borough of Gateshead 10,700 476 South Tyneside Accessible location(s) within the Borough of South Tyneside 7,900 351 Sunderland North Minimum of two sites - 1 x accesible location in Washington, and 1 other, ie Castle, Redhill or Southwick wards 9,000 400 Sunderland South Accessible location(s) South of River Wear (City Centre location, ie Millfield, Hendon, St Michael's wards) 16,000 711 Northumberland Central Accessible location(s) within Central Northumberland, ie Ashington. 9,000 400 Northumberland -

Middlesbrough Ward: Brambles and Thorntree Polling District: IA

Electoral Division: Middlesbrough Parliamentary Constituency: Middlesbrough Ward: Brambles and Thorntree Polling District: IA POLLING STATION LOCATION: Brambles Farm Community Centre, Marshall Avenue, TS3 9AY TOTAL ELECTORS: 1888 TURNOUT: Combination of 2 existing stations, so no direct comparison. STREETS COVERED (See attached map): Cargo Fleet Lane, Falcon Road, Hawk Road, Kestrel Avenue, Longlands Road, Merlin Road, Alexander Terrace, Aston Avenue, Barrass Grove, Berwick Hills Avenue, Burnholme Avenue, Cherwell Terrace, College Road, Cranfield Avenue, Ferndale Avenue, Ferndale Court, Grimwood Avenue, Hanson Grove, Hatherley Court, Hopkins Avenue, Ings Avenue, Kedward Avenue, Lilac Grove, Lowfield Avenue, Marshall Avenue, Marshall Court, Matford Avenue, Millbrook Avenue, Northfleet Avenue, Pallister Avenue, Pallister Court, Thorntree Avenue, Tomlinson Way, Turford Avenue, Villa Road, Weston Avenue, Winslade Avenue. ELECTORAL OFFICERS COMMENTS: Location & suitability Existing station familiar to residents. Centrally located within the residential area of the polling district. The previous mobile station on Cargo Fleet Lane has been combined into this station as this served a very small number of electors (283). Mobile stations cost approximately 3 times the cost of a station located within a public building. Parking Nearby on street parking Access Fully accessible Facilities for staff Satisfactory Recommendation Most suitable building within polling district. RETURNING OFFICERS COMMENTS: This polling station has been used for several -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939 Jennings, E. How to cite: Jennings, E. (1965) The development of education in the North Ridings of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9965/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Abstract of M. Ed. thesis submitted by B. Jennings entitled "The Development of Education in the North Riding of Yorkshire 1902 - 1939" The aim of this work is to describe the growth of the educational system in a local authority area. The education acts, regulations of the Board and the educational theories of the period are detailed together with their effect on the national system. Local conditions of geograpliy and industry are also described in so far as they affected education in the North Riding of Yorkshire and resulted in the creation of an educational system characteristic of the area. -

Middlesbrough Boundary Special Protection Area Potential Special

Middlesbrough Green and Blue Infrastructure Strategy Middlesbrough Council Middlesbrough Cargo Fleet Stockton-on-Tees Newport North Ormesby Brambles Farm Grove Hill Pallister Thorntree Town Farm Marton Grove Berwick Hills Linthorpe Whinney Banks Beechwood Ormesby Park End Easterside Redcar and Acklam Cleveland Marton Brookfield Nunthorpe Hemlington Coulby Newham Stainton Thornton Hambleton 0 1 2 F km Map scale 1:40,000 @ A3 Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2020 CB:KC EB:Chamberlain_K LUC 11038_001_FIG_2_2_r0_A3P 08/06/2020 Source: OS, NE, MC Figure 2.2: Biodiversity assets in and around Middlesbrough Middlesbrough boundary Local Nature Reserve Special Protection Area Watercourse Potential Special Protection Area Priority Habitat Inventory Site of Special Scientific Interest Deciduous woodland Ramsar Mudflats Proposed Ramsar No main habitat but additional habitats present Ancient woodland Traditional orchard Local Wildlife Site Middlesbrough Green and Blue Infrastructure Strategy Middlesbrough Council Middlesbrough Cargo Fleet Stockton-on-Tees Newport North Ormesby Brambles Farm Grove Hill Pallister Thorntree Town Farm Marton Grove Berwick Hills Linthorpe Whinney Banks Beechwood Ormesby Park End Easterside Redcar and Acklam Cleveland Marton Brookfield Nunthorpe Hemlington Coulby Newham Stainton Thornton Hambleton 0 1 2 F km Map scale 1:40,000 @ A3 Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2020 CB:KC EB:Chamberlain_K LUC 11038_001_FIG_2_3_r0_A3P 29/06/2020 Source: OS, NE, EA, MC Figure 2.3: Ecological Connection Opportunities in Middlesbrough Middlesbrough boundary Working With Natural Processes - WWNP (Environment Agency) Watercourse Riparian woodland potential Habitat Networks - Combined Habitats (Natural England) Floodplain woodland potential Network Enhancement Zone 1 Floodplain reconnection potential Network Enhancement Zone 2 Network Expansion Zone. -

Councillor Submissions to the Middlesbrough Borough Council Electoral Review

Councillor submissions to the Middlesbrough Borough Council electoral review. This PDF document contains 9 submissions from councillors. Some versions of Adobe allow the viewer to move quickly between bookmarks. Click on the submission you would like to view. If you are not taken to that page, please scroll through the document. Cllr Bernie Taylor Middlesbrough Council Town Hall Middlesbrough TS1 2QQ The Local Government Boundary Commission for England, Layden House 76-86 Turnmill Street London EC1M 5LG To the members and officers of the Commission, Having seen the Draft Recommendations for Middlesbrough which you have produced, I would like to thank you for the time and effort you no doubt spent on the plans. I would, however, like to draw your attention to a small row of houses whose residents I feel would be better served in the Newport Ward which you propose. I would also like to request that the name of the proposed Ayresome ward be changed to Acklam Green to reflect the local community and provide a clearer identity for the ward. There is a street of around fifteen properties whose residents would be better served if they were part of the proposed Newport ward. The houses run along the south side of Stockton Road – known colloquially as the ‘Wilderness Road.’ This road is cut off from the rest of the Aryesome ward by the A66 and isolated from the mane population centre of the proposed Aryesome ward by the Teesside Park Leisure complex. However, Stockton Road is easily accessed from the proposed Newport Road as the road travels under the A19 flyover. -

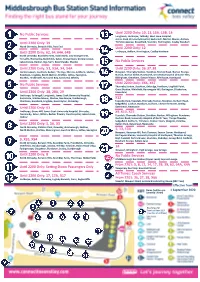

Middlesbrough Bus Station

No Public Services Until 2200 Only: 10, 13, 13A, 13B, 14 Longlands, Linthorpe, Tollesby, West Lane Hospital, James Cook University Hospital, Easterside, Marton Manor, Acklam, Until 2200 Only: 39 Trimdon Avenue, Brookfield, Stainton, Hemlington, Coulby Newham North Ormesby, Berwick Hills, Park End Until 2200 Only: 12 Until 2200 Only: 62, 64, 64A, 64B Linthorpe, Acklam, Hemlington, Coulby Newham North Ormesby, Brambles Farm, South Bank, Low Grange Farm, Teesville, Normanby, Bankfields, Eston, Grangetown, Dormanstown, Lakes Estate, Redcar, Ings Farm, New Marske, Marske No Public Services Until 2200 Only: X3, X3A, X4, X4A Until 2200 Only: 36, 37, 38 Dormanstown, Coatham, Redcar, The Ings, Marske, Saltburn, Skelton, Newport, Thornaby Station, Stockton, Norton Road, Norton Grange, Boosbeck, Lingdale, North Skelton, Brotton, Loftus, Easington, Norton, Norton Glebe, Roseworth, University Hospital of North Tees, Staithes, Hinderwell, Runswick Bay, Sandsend, Whitby Billingham, Greatham, Owton Manor, Rift House, Hartlepool No Public Services Until 2200 Only: X66, X67 Thornaby Station, Stockton, Oxbridge, Hartburn, Lingfield Point, Great Burdon, Whinfield, Harrowgate Hill, Darlington, (Cockerton, Until 2200 Only: 28, 28A, 29 Faverdale) Linthorpe, Saltersgill, Longlands, James Cook University Hospital, Easterside, Marton Manor, Marton, Nunthorpe, Guisborough, X12 Charltons, Boosbeck, Lingdale, Great Ayton, Stokesley Teesside Park, Teesdale, Thornaby Station, Stockton, Durham Road, Sedgefield, Coxhoe, Bowburn, Durham, Chester-le-Street, Birtley, Until -

The Council of the Borough of Middlesbrough (Woodlands Road / Southfield Road / Fern Street) Temporary Traffic Regulation Order 2020

THE COUNCIL OF THE BOROUGH OF MIDDLESBROUGH (WOODLANDS ROAD / SOUTHFIELD ROAD / FERN STREET) TEMPORARY TRAFFIC REGULATION ORDER 2020 NOTICE is hereby given that on 21st April 2020 Middlesbrough Council made an Order which prevents vehicles from using the lengths of road set out below due to redevelopment / improvement works by Teesside University taking place on or near the road because of the likelihood of danger to the public. Access for pedestrians and the emergency services will be maintained at all times. Access will also be provided for vehicles used in connection with maintenance and works carried out by statutory undertakers. The roads will be closed during the programmed dates shown below for up to 18 months or until the works have been completed and there is no longer a danger to the public. If the works are not completed within 18 months, the Order may be extended with the approval of the Secretary of State. Dated 23rd April 2020 Charlotte Benjamin Director of Legal and Governance Services Town Hall Middlesbrough TS1 9FX Location Description Programmed Dates Woodlands Road from its junctions with the southern kerbline of Clarendon 8/6/20 - 10/8/20 Road to the northern kerbline of Southfield Road. Southfield Road from a point 5m west of its junction with the western 20/7/20 - 10/8/20 kerbline of Woodlands Road to a point 15m east of its junction with the eastern kerbline of Woodlands Road. Southfield Road (northern parking bays only) from a point 6m west of its 27/4/20 - 10/8/20 junction with the western kerbline of Fern Street for a distance of 18m in a westerly direction. -

Parish Profile

1 Parish Profile 2017 Church of the Ascension Penrith Road, Berwick Hills Middlesbrough TS3 7JR 2 A letter from the Bishops of Beverley and of Whitby Thank you for looking at our parish profile. In the pages that follow, you can see how the people of the parish of the Ascension describe their community and church, and the possibilities they see for moving forward in company with their new priest. The parish was led for over 20 years by Canon David Hodgson, who died in office in October 2016. He was a much loved larger-than-life character who is greatly missed by parishioners and by colleagues across the diocese. David laid a secure foundation of sacramental worship, prayer and study, and that legacy is something that we would all want to see honoured in the future. The liturgical style of the parish’s formal worship is distinctively modern catholic. David combined his personal Traditionalist Catholic stance with a generous spirit of committed collaboration with clergy and parishes representing the spectrum of Anglicanism. The parish is designated to receive the extended episcopal care of the Bishop of Beverley, whilst maintaining close contact with the Archbishop and with the Bishop of Whitby. In the time since David’s death there has been much prayerful thinking in the parish, in conjunction with us. Among the worshippers at the Ascension there are some who in conscience cannot receive the sacramental ministry of female clergy, and others who do not hold a Traditionalist position. Everyone involved in these conversations agrees that it would be damaging to the life and mission of the parish if this matter were to become a cause of division, when there are opportunities to take God’s work in this community forward together. -

The Council of the Borough of Middlesbrough (South Area) (Waiting and Loading and Parking Places) (Consolidation) Order 2006

THE COUNCIL OF THE BOROUGH OF MIDDLESBROUGH (SOUTH AREA) (WAITING AND LOADING AND PARKING PLACES) (CONSOLIDATION) ORDER 2006 The Council of the Borough of Middlesbrough ('the Council') in exercise of its powers under Sections 1(1) and(2), 2(1) to (3) 3(2) 32(1) 35 45 46 46A 47 49 51 and 53 and Part IV of Schedule 9 to the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984, as amended, ('the Act') and of all other enabling powers and after consultation with the Chief Officer of Police in accordance with Part III of Schedule 9 to the Act, hereby makes the following Order: DEFINITIONS In this Order all expressions except as otherwise herein provided shall have the meanings assigned to them by the Act. “disabled person's badge” has the same meaning as in the Disabled Persons (Badges for Motor Vehicles) (England) Regulations 2000 “disabled person's vehicle” means a vehicle lawfully displaying a disabled person's badge. “driver” in relation to a vehicle waiting in a parking place, means the person driving the vehicle at the time it was left in the parking place. “dual purpose vehicle” has the same meaning as in Regulation 3 of the Road Vehicles (Construction and Use) Regulations 1986, as amended. “freehold owner” means the owner of premises used for business purposes situated adjacent to a permit parking place more particularly set out in Schedule 10 to this Order. “goods vehicle” means a motor vehicle which is constructed or adapted for use for the carriage of goods or burden of any description and which has an unladen weight not exceeding 7.5 tonnes and is not drawing a trailer. -

Middlesbrough Designations List

Middlesbrough Local Authority Area: Designated Sites Statutory Site Name Reason for Designation Site Grid Reference designated sites (National) Site of Special Scientific Langbaurgh Ridge Identified as of national importance in the Geological Conservation Review. NZ 556 121 Interest (SSSI) Local non-statutory Site Name Reason for Designation Site Grid Reference designated sites LWS Newham Beck Watercourse NZ51C - NZ41X - NZ41Y LWS Marton West Beck Watercourse NZ51C - NZ41X - NZ41Y LWS Middlebeck Watercourse; M4 (Water Vole) NZ 521 188 to NZ 527 177 LWS Whinney Banks Pond Pond and surrounding marsh/damp grassland NZ 476 184 LWS Anderson's Field (Marton G1 (Neutral Grasslands) West Beck) NZ 515 147 LWS Berwick Hill & Ormesby G1 (Neutral Grasslands) Beck Complex NZ 508 192 to NZ 519 169 LWS Bonny Grove (Marton G1 (Neutral Grasslands) West Beck) NZ 527 139 to NZ 522 138 1 Local non- Site Name Reason for Designation Site Grid Reference statutory designated sites LWS Maltby Beck G1 (Neutral Grasslands) NZ 471 135 LWS Maltby Beck G1 (Neutral Grasslands) NZ 474 135 LWS Bluebell Beck Complex G1 (Neutral Grasslands); M4 (Water Vole) NZ 471 170 to NZ 478 164 LWS Maze Park U1 (Urban Grasslands) NZ 469 192 LWS Old River Tees C1 (Saltmarsh) NZ 472 182 LWS Plum Tree Pasture G1 (Neutral Grasslands) NZ 468 143 LWS Grey Towers Park W2 (Broad-leaved Woodland and Replanted Ancient Woodland) (formerly Poole Hospital) NZ 533 135 LWS Stainsby Wood W1 (Ancient Woodland) NZ 463 148 LWS Teessaurus Park U1 (Urban Grasslands) NZ 486 218 LWS Thornton Wood and Pond -

Isolation Pack

Dear Parents / Carers of Abbey Hill Academy To support our families during this uncertain time we have put together an information pack detailing information and contacts that we feel might be of use to you: Useful Contacts / website Family & Community Hub details Safeguarding information Suggestions for isolation Foodbank details Abbey Hill Academy contact details during any period of isolation or school closure: Website: https://abbeyhill.horizonstrust.org.uk/ Email: [email protected] Parent Support: [email protected] Abbey Hill Academy: 01642 677113 Mobile: 07885462234 (contactable between 9-3.30) If you email or ring me and I am unavailable and you require urgent advice then please refer to the contact sheet below. Useful Contacts Organisation Telephone Website Anti-Social Behaviour 01642 607943 Team Citizens Advice Helpline 0344 411 1444 https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/ CAMHS (Inc. learning 0300 013 2000 https://www.tewv.nhs.uk/ disability) Option 2 – Middlesbrough Option 3 – Redcar Option 4 – Hartlepool Option 5 – Stockton Option 6 – Crisis and liaison team Option 7 – Specialist eating disorders service (Teesside) DLA Helpline 0800 1214600 Family Information Service Stockton http://stocktoninformationdirectory.org/ Hartlepool https://hartlepool.fsd.org.uk/ Middlesbrough https://fis.middlesbrough.gov.uk/ Redcar http://www.peoplesinfonet.org.uk/ Harbour Services https://www.myharbour.org.uk/ Stockton 0300 020 2525 Hartlepool 01429 270110 Middlesbrough 01642 861788 My Sister’s Place 01642 241864 -

The London Gazette, 28 April, 1931

2744. THE LONDON GAZETTE, 28 APRIL, 1931. there by Norton Boad, Billingham Eoad, (2) In the Rural District of Stockton:— Belasis Lane ,and Avenue to the Transporter ••Yarm Boad, Tees Boad. Bridge (Port. Clarence). (4) As per Route (3) described jabove to (3) In the Rural District of Sto&esley:— Billingham Eoad, along that road thence by Yarm High Street, Leven Boad, Leven Bank, New Boad, Chilton Lane to Transporter Yarm Bank, Spital Lane, Thornaby Boad. Bridge" (Port Clarence). (4) In the Borough of Thornaby-on-Tees:— (5) Between Exchange Place, Middles- Victoria Bridge, Mandale Boad, Westbury brough, and Town Hall, Stockton-on-Tees, via Street, Boseberry Crescent, Cheltenham Newport Boad. Avenue, Mansfield Avenue, Cobden Street, (6) Between Exchange Place, Middles- Acklam Boad, Thornaby Boad, Middlesbrough brough, via Linthorpe Boad and Acklam Boad, Boad, Lanehouse Boad. - to Town Hall, Stockton-on-Tees. (5) In* the Rural District of Middlesbrough:— (7) Between North Ormesby, Middlesbrough, and Norton Green, Stockton-on-Tees, by New- Acklam Eoad, Newport Lane. port Eoad. (6) In the Borough of Middlesbrough:— (8) On certain roads in the Urban District Stockton Boad, Newport Boad, Corporation of Billingham in connection with the co- Boad, Albert Boad, Exchange Place, Newport ordination of services. Lane, Cambridge Boad, Orchard Boad, The Notice is also given that any Local Avenue, Linthorpe Boad, Borough Boad West, Authority, the Council of any County, or any North Ormesby Boad. persons who are already providing transport facilities on or in the neighbourhood of any (7) In the Rural District of Hartlepool:— part of any route to which the application Tees Boad.