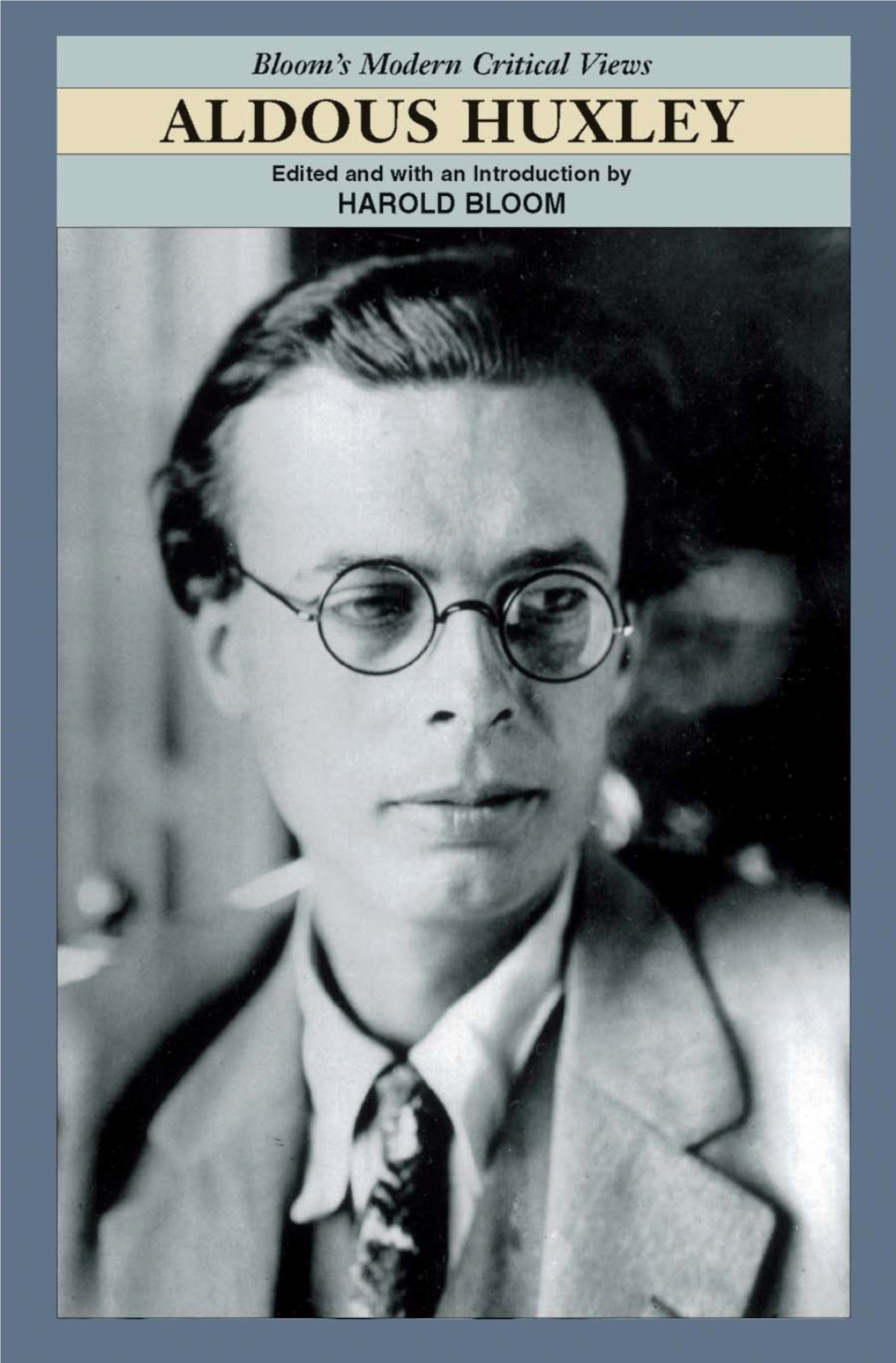

Aldous Huxley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Individuation in Aldous Huxley's Brave New World and Island

Maria de Fátima de Castro Bessa Individuation in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and Island: Jungian and Post-Jungian Perspectives Faculdade de Letras Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais Belo Horizonte 2007 Individuation in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and Island: Jungian and Post-Jungian Perspectives by Maria de Fátima de Castro Bessa Submitted to the Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras: Estudos Literários in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Mestre em Letras: Estudos Literários. Area: Literatures in English Thesis Advisor: Prof. Julio Cesar Jeha, PhD Faculdade de Letras Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais Belo Horizonte 2007 To my daughters Thaís and Raquel In memory of my father Pedro Parafita de Bessa (1923-2002) Bessa i Acknowledgements Many people have helped me in writing this work, and first and foremost I would like to thank my advisor, Julio Jeha, whose friendly support, wise advice and vast knowledge have helped me enormously throughout the process. I could not have done it without him. I would also like to thank all the professors with whom I have had the privilege of studying and who have so generously shared their experience with me. Thanks are due to my classmates and colleagues, whose comments and encouragement have been so very important. And Letícia Magalhães Munaier Teixeira, for her kindness and her competence at PosLit I would like to express my gratitude to Prof. Dr. Irene Ferreira de Souza, whose encouragement and support were essential when I first started to study at Faculdade de Letras. I am also grateful to Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for the research fellowship. -

Brave New World

BRAVE NEW WORLD by Aldous Huxley (1894-1963) Chapter One A SQUAT grey building of only thirty-four stories. Over the main en- trance the words, CENTRAL LONDON HATCHERY AND CONDITIONING CENTRE, and, in a shield, the World State's motto, COMMUNITY, IDEN- TITY, STABILITY. The enormous room on the ground floor faced towards the north. Cold for all the summer beyond the panes, for all the tropical heat of the room itself, a harsh thin light glared through the windows, hungrily seeking some draped lay figure, some pallid shape of academic goose- flesh, but finding only the glass and nickel and bleakly shining porce- lain of a laboratory. Wintriness responded to wintriness. The overalls of the workers were white, their hands gloved with a pale corpse- coloured rubber. The light was frozen, dead, a ghost. Only from the yellow barrels of the microscopes did it borrow a certain rich and living substance, lying along the polished tubes like butter, streak after luscious streak in long recession down the work tables. "And this," said the Director opening the door, "is the Fertilizing Room." Bent over their instruments, three hundred Fertilizers were plunged, as the Director of Hatcheries and Conditioning entered the room, in the scarcely breathing silence, the absent-minded, soliloquizing hum or whistle, of absorbed concentration. A troop of newly arrived students, very young, pink and callow, followed nervously, rather abjectly, at the Director's heels. Each of them carried a notebook, in which, whenever the great man spoke, he desperately scribbled. Straight from the horse's mouth. It was a rare privilege. -

Brave New World: the Correlation of Social Order and the Process Of

Brave New World: The Correlation of Social Order and the Process of Literary Translation by Maria Reinhard A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in German Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2008 ! Maria Reinhard 2008 Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This comparative analysis of four different German-language versions of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) shows the correlation between political and socio- cultural circumstances, as well as ideological differences, and translations of the novel. The first German translation was created by Herberth E. Herlitschka in 1932, entitled Welt – Wohin? Two further versions of it were released in 1950 and 1981. In 1978, the East German publisher Das Neue Berlin published a new translation created by Eva Walch, entitled Schöne neue Welt. My thesis focuses on the first translations by both Herlitschka and Walch, but takes into account the others as well. The methodological basis is Heidemarie Salevsky’s tripartite model. With its focus on author and work, commissioning institution and translator, it was developed as a tool to determine the factors influencing the process of literary translation. Within this framework, the translations are contextualized within the cultural and political circumstances of the Weimar and German Democratic Republics, including an historical overview of the two main publishers, Insel and Das Neue Berlin. -

Postcolonial Utopias Or Imagining 'Brave New Worlds'

Postcolonial Utopias or Imagining ‘Brave New Worlds’: Caliban Speaks Back Corina Kesler │ University of Michigan Citation: Corina Kesler, “Postcolonial Utopias or Imagining ‘Brave New Worlds’: Caliban Speaks Back”, Spaces of Utopia: An Electronic Journal, 2nd series, no. 1, 2012, pp. 88-107<http://ler.letras.up.pt > ISSN 1646-4729. “this is the oppressor’s language, yet I need it to speak to you” bell hooks1 I have recently completed a doctoral project that focused on lesser-known utopian expressions from non-Western cultures such as Romania, the pre-Israel Jewish diaspora, and postcolonial countries like Nigeria, Ghana, and India. I hypothesized a causal relationship between the conditions of oppression and expressions of utopia. Roughly: the more a people, culture, and/or ethnicity experience physical space as a site of political, cultural, and literal encroachment, the more that distinct culture’s utopian ideas tend to appear in non-spatial, specifically, temporal formulations. Under the pressures of oppression, the specific character of an ethnic group/individual, having been challenged within a (often national) space, seeks not a ‘where’ (utopia), but a ‘when’ (uchronia or intopia) of mythical, or mystical time. And it is there, or rather, then, where oppressed groups give the utopian impulse expression, and define, protect, and develop their own identity. To support this hypothesis, I examined in detail texts like Mircea Eliade’s The Forbidden Forest, Sergiu Fărcășan’s A Love Story from the Year 41,042, Bujor Nedelcovici’s The Second Messenger, Oana Orlea’s Perimeter Zero, Costache Olareanu’s Fear; Ben Okri’s Astonishing the Gods; Kajo Laing’s Major Gentl and the Achimota Wars; Amitav Ghosh’s The Calcutta Chromosome: A Novel of Fevers, Delirium and Discovery; and The Zohar: The Book of Splendor, and practices like the Sabbath in Classical Kabbalah and the Păltiniș Paidetic school in Romania. -

Brave New World"

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2003 "In that New World which is the Old": New World/Old World inversion in Aldous Huxley's "Brave New World" Oliver Quimby Melton University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Melton, Oliver Quimby, ""In that New World which is the Old": New World/Old World inversion in Aldous Huxley's "Brave New World"" (2003). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1603. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/mf63-axmr This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "IN THAT NEW WORLD WHICH IS THE OLD": NEW WORLD/OLD WORLD INVERSION IN ALDOUS HUXLEY'S BRAVE NEW WORLD by Oliver Quimby Melton Bachelor of Arts, cum laude University of Georgia December 2000 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in English Department of English College of Liberal Arts UNLV Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2003 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

The New China: Big Brother, Brave New World Or Harmonious Society?

ARTICLE .15 The New China: Big Brother, Brave New World or Harmonious Society? Marcus Anthony University of the Sunshine Coast Australia Abstract In this paper I examine three textual mythologies regarding China's evolving present. These are an Orwellian world of covert and overt state control; a Brave New World dystopia where the spirit of the people is subsumed in hedonistic distractions; and finally I assess the progress towards the official vision of the cur- rent Beijing authorities: the "harmonious society". These three "pulls" of the future are juxtaposed with certain key "pushes" and "weights", and I explore their interplay within a "futures triangle". Finally, I suggest whether any of these mythologies is likely play a significant role in the possible futures of China. Key words: mythology, utopia, dystopia, democracy, accountability, development, hedonism, human rights, harmonious society, corruption, materialism, environment, globalisation, healing, nationalism, totalitarianism. The New China: Big Brother, Brave New World or Harmonious Society? Independent thinking of the general public, their newly-developed penchant for independent choices and thus the widening gap of ideas among different social strata will pose further chal- lenges to China's policy makers... Negative and corruptive phenomena and more and more rampant crimes in the society will also jeopardize social stability and harmony. Chinese President Hu Jintao ("Building Harmonious", 2005) The fact is that China has experienced its golden period of economic and social development in the past decade. In 2004, for example, GDP grew by about 9.5 percent, with growth in con- sumer prices kept to about 3 percent... This also is a period of decisive importance, when a country's per capita GDP reaches US$1,000 to 3,000. -

Brave New World Essays

Huxley’s Brave New World: Essays Huxley’s Brave New World: Essays edited by DAVID GARRETT IZZO and KIM KIRKPATRICK McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London McFarland has also published the following works: W. H. Auden Encyclopedia (2004), Christopher Isherwood Encyclopedia (2005), and The Writings of Richard Stern: The Education of an Intellectual Everyman (2002), by David Garrett Izzo. Henry James Against the Aesthetic Movement: Essays on the Middle and Late Fiction (2006), edited by David Garrett Izzo and Daniel T. O’Hara. Stephen Vincent Benét: Essays on His Life and Work (2003), edited by David Garrett Izzo and Lincoln Konkle. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Huxley’s Brave new world : essays / edited by David Garrett Izzo and Kim Kirkpatrick. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-¡3 978-0-7864-3683-5 softcover : 50# alkaline paper ¡. Huxley, Aldous, ¡894–¡963. Brave new world. 2. Huxley, Aldous, ¡894–¡963—Political and social views. 3. Huxley, Aldous, ¡894–¡963—Philosophy. 4. Dystopias in literature. I. Izzo, David Garrett. II. Kirkpatrick, Kim, ¡962– PR60¡5.U9B675 2008 823'.9¡2—dc22 20080¡3463 British Library cataloguing data are available ©2008 David Garrett Izzo. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover illustration ©2008 Shutterstock Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 6¡¡, Je›erson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Carol A. -

Altered States: the American Psychedelic Aesthetic

ALTERED STATES: THE AMERICAN PSYCHEDELIC AESTHETIC A Dissertation Presented by Lana Cook to The Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April, 2014 1 © Copyright by Lana Cook All Rights Reserved 2 ALTERED STATES: THE AMERICAN PSYCHEDELIC AESTHETIC by Lana Cook ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University, April, 2014 3 ABSTRACT This dissertation traces the development of the American psychedelic aesthetic alongside mid-twentieth century American aesthetic practices and postmodern philosophies. Psychedelic aesthetics are the varied creative practices used to represent altered states of consciousness and perception achieved via psychedelic drug use. Thematically, these works are concerned with transcendental states of subjectivity, psychic evolution of humankind, awakenings of global consciousness, and the perceptual and affective nature of reality in relation to social constructions of the self. Formally, these works strategically blend realist and fantastic languages, invent new language, experimental typography and visual form, disrupt Western narrative conventions of space, time, and causality, mix genres and combine disparate aesthetic and cultural traditions such as romanticism, surrealism, the medieval, magical realism, science fiction, documentary, and scientific reportage. This project attends to early exemplars of the psychedelic aesthetic, as in the case of Aldous Huxley’s early landmark text The Doors of Perception (1954), forgotten pioneers such as Jane Dunlap’s Exploring Inner Space (1961), Constance Newland’s My Self and I (1962), and Storm de Hirsch’s Peyote Queen (1965), cult classics such as Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968), and ends with the psychedelic aesthetics’ popularization in films like Roger Corman’s The Trip (1967). -

Miranda's Dream Perverted: Dehumanization in Huxley's Brave

MIRANDA’S DREAM PERVERTED: DEHUMANIZATION IN HUXLEY’S BRAVE NEW WORLD A thesis submitted to the Kent State University Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for General Honors by Paul C. Chizmar May, 2012 Thesis written by Paul C. Chizmar Approved by , Advisor , Chair, Department of English Accepted by , Dean, Honors College ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS……………………………………………………v CHAPTERS I. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………..1 II. DEHUMANIZATION IN THE WORLD STATE…………….8 A Definition of the Human Element……………………………9 Methods of Dehumanization……………………………………14 Eugenics………………………………………………...14 Opiates of the Masses…………………………………..17 Dehumanization and Conditioning……………………………..22 Last Vestiges of Humanity……………………………………..25 Implications…………………………………………………….26 III. SEEDS OF DISSENT………………………………………….27 Setting the Stage: Character Introductions……………………..28 Bernard Marx……………………………………………28 Lenina Crowne…………………………………………..29 Helmholtz Watson……………………………………….31 John the Savage………………………………………….32 The Wheels are put into Motion…………………………………33 Face to Face with Mustapha Mond………………………………42 The Journey Ends………………………………………………..43 Implications………………………………………………………45 IV. INFLUENCES BEHIND THE BOOK………………………….48 Brave New World as Utopian Parody……………………………48 iii Brave New World and Actual Utopian Ideas……………………51 Globalization…………………………………………….51 Eugenics…………………………………………………52 Comfort and Leisure…………………………………….54 Beyond Utopia…………………………………………………..55 Industrialism/Consumerism……………………………...56 Contemporary Entertainment…………………………….58 Implications………………………………………………………61 -

Looking at the Sport of Boxing Joseph Lee

Document generated on 10/01/2021 3:07 a.m. Canadian Journal of Bioethics Revue canadienne de bioéthique Adverse Health and Psychosocial Repercussions in Retirees from Sports Involving Head Trauma: Looking at the Sport of Boxing Joseph Lee Volume 4, Number 1, 2021 Article abstract Academic scholarship has steadily reported unfavourable clinical findings on URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1077632ar the sport of boxing, and national medical bodies have issued calls for DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1077632ar restrictions on the sport. Yet, the positions taken on boxing by medical bodies have been subject to serious discussions. Beyond the medical and legal See table of contents writings, there is also literature referring to the social and cultural features of boxing as ethically significant. However, what is missing in the bioethical literature is an understanding of the boxers themselves. This is apart from Publisher(s) their brain injuries, the debates about the degenerative brain disease known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), and related issues about the disease. Programmes de bioéthique, École de santé publique de l'Université de This article argues that the lives of boxers, their relationships, their careers, Montréal and their futures, also requires its own research, particularly in telling stories about their lives, and those lives and futures which boxing affects. The article ISSN uses two approaches. First, to imagine a more enduring “whole of life viewpoint” by using an extended future timeframe. Second, to consider 2561-4665 (digital) perspectives of a person’s significant others. After reviewing the boxing literature, the article discusses social settings and then explores the hidden Explore this journal social relationships in life after boxing. -

1948 (4.052Mb)

From National Public Relations. Division, The American Legion, Indianapolis, Indiana. Suggested 1948 Armistice Day Address for American Legion speakers. MY FELLOW AMERICANS: Armistice Day has a special American meaning. It is a reminder to all enemies of liberty that Americans love freedom more than life, that they are ready to fight to the death to remain free. On April 2, 1917, addressing Congress, President Woodrow Wilson used the words: * "The world must be made safe for democracy." It was a phrase that many made a bitter joke of after World War I. But it was not a joke. 123,654 Americans died in its defense. On December 9, 1941, speaking to the nation, President Franklin D. Roosevelt said: "Together with other free peoples, we are now fighting to maintain our right to live among our world neighbors in freedom and in common decency without fear of assaults," 353,967 Americans died to make good those words, Today we honor the memory of the dead of both of these wars. Our hearts go out to those still suffering from their wounds. There are still uncounted thousands of brave Americans for whom these wars are not yet over and may never be over. The American Legion is dedicated to helping them carry their heavy burdens. They must never be forgotten. Every American owes his freedom today to these heroes of war, both living and dead. Their willingness to sacrifice was the final proof of American determination to stay free. Let no world aggressor, think, even for a moment, that Americans would not go forth again to battle in freedom’s cause! America is the stronghold of liberty.