Chosen by God: the Female Itinerants of Early Primitive Methodism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 'Wild' Sheep of Britain

The 'Wild' Sheep of Britain </. C. Greig and A. B. Cooper Primitive breeds of sheep and goats, such as the Ronaldsay sheep of Orkney, could be in danger of disappearing with the present rapid decline in pastoral farming. The authors, both members of the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources in Edinburgh University, point out that, quite apart from their historical and cultural interest, these breeds have an important part to play in modern livestock breeding, which needs a constant infusion of new genes from unimproved breeds to get the benefits of hybrid vigour. Moreover these primitive breeds are able to use the poor land and live in the harsh environment which no modern hybrid sheep can stand. Recent work on primitive breeds of sheep and goats in Scotland has drawn attention not only to the necessity for conserving them, but also to the fact that there is no organisation taking a direct scientific in- terest in them. Primitive livestock strains are the jetsam of the Agricul- tural Revolution, and they tend to survive in Europe's peripheral regions. The sheep breeds are the best examples, such as the sheep of Ushant, off the Brittany coast, the Ronaldsay sheep of Orkney, the Shetland sheep, the Soay sheep of St Kilda, and the Manx Loaghtan breed. Presumably all have survived because of their isolation in these remote and usually infertile areas. A 'primitive breed' is a livestock breed which has remained relatively unchanged through the last 200 years of modern animal-breeding techniques. The word 'primitive' is perhaps unfortunate, since it implies qualities which are obsolete or undeveloped. -

Deborah Schiffrin Editor

Meaning, Form, and Use in Context: Linguistic Applications Deborah Schiffrin editor Meaning, Form, and Use in Context: Linguistic Applications Deborah Schiffrin editor Georgetown University Press, Washington, D.C. 20057 BIBLIOGRAPHIC NOTICE Since this series has been variously and confusingly cited as: George- town University Monographic Series on Languages and Linguistics, Monograph Series on Languages and Linguistics, Reports of the Annual Round Table Meetings on Linguistics and Language Study, etc., beginning with the 1973 volume, the title of the series was changed. The new title of the series includes the year of a Round Table and omits both the monograph number and the meeting number, thus: Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics 1984, with the regular abbreviation GURT '84. Full bibliographic references should show the form: Kempson, Ruth M. 1984. Pragmatics, anaphora, and logical form. In: Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics 1984. Edited by Deborah Schiffrin. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. 1-10. Copyright (§) 1984 by Georgetown University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalog Number: 58-31607 ISBN 0-87840-119-9 ISSN 0196-7207 CONTENTS Welcoming Remarks James E. Alatis Dean, School of Languages and Linguistics vii Introduction Deborah Schiffrin Chair, Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics 1984 ix Meaning and Use Ruth M. Kempson Pragmatics, anaphora, and logical form 1 Laurence R. Horn Toward a new taxonomy for pragmatic inference: Q-based and R-based implicature 11 William Labov Intensity 43 Michael L. Geis On semantic and pragmatic competence 71 Form and Function Sandra A. -

231 BOOK REVIEWS John Pritchard

Methodist History, 52:4 (July 2014) BOOK REVIEWS John Pritchard, Methodists and Their Mission Societies, 1760-1900. Surrey, England: Ashgate Publishing, 2013. 318 pp. £63. Methodists and Their Mission Societies, 1760-1900, is the first part of a two-volume series by John Pritchard about British Methodist mission work around the world. The publication of this series marks the two hundredth anniversary of the first meeting of the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society (WMMS) in October of 1883 in Leeds. Moreover the book updates the 1913 five volume work by G.G. Findlay and W.W. Holdsworth entitled The History of the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society (Epworth). The focus of this work is further broadened and includes the mission work of four other denominations (Primitive Methodists, Methodist New Connexion, United Methodist Free Churches and Bible Christians) under the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society to become the Methodist Mission Society in 1932. Pritchard records in great detail the early Methodist mission efforts around the world including the roles of John Wesley, Thomas Coke, Jabez Bunting and other mission proponents. Beginning with the backdrop of six- teenth-century Catholic and late seventeenth-century to early eighteenth-cen- tury German Pietist mission work, the book quickly focuses on the British context. The author describes the priority of the Society for the Promotion of the Gospel (SPG) to provide for the spiritual needs of the colonists before evangelizing native peoples. William Caray’s 1792 Enquiry, which led to the creation of the Baptist Missionary Society, and Thomas Coke’s apoca- lyptic urgency heightened this priority, however the tension between empire and mission to the indigenous remained for several decades—varying from country to country. -

Jabez Bunting

JA BEZ B U N T I N G A GREAT METHO DIST LEA DER I D . REV. MES H RR N R G D O G . JA A IS , T HE M D ETHO IST BOO' CON C ERN . N EW 'OR ' C I CI AT I N NN . P R E 'A C E N o o ne can feel more deeply than the writer how inadequate is the little book he h a s i written , when crit cally regarded as a life - sketch of the greatest man o f middle Methodism , to whose gifts and character organized Wesleyan Methodism throughout the world owes incomparably more than to any other man , With more Space a better book might and ought to have been made . But to bring the book within reach of every intelligent and earnest Methodist youth and ’ o f every working man s family , a very cheap volume was necessary , and therefore a very small one . The writer has done his best, w accordingly , to meet the vie s of the Metho dist Publishing House in this matter . He knows how great and serious are some o f the deficiencies in this record ; especially 6 Pre fa ce o n i the side of Methodist Fore gn Missions , hi as to w ch he has said nothing , though Jabez Bunting in this field was the prime and most influential organizer in all the early ’ years of o u r Church s Connexional mission work and world -wide enterprises The subject was too large and wide , too various and too complicated , to be dealt with in a section of a small book . -

Paper for the Oxford Institute of Methodist Theological Studies, August 2007 History of Methodism Working Group

Paper for the Oxford Institute of Methodist Theological Studies, August 2007 History of Methodism Working Group A Calling to Fulfill: Women in 19th Century American Methodism Janie S. Noble In Luke’s account of the resurrection, it is women, Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Mary the mother of James, and the other women who take the message of the empty tomb to the apostles (24:10).1 The Old and New Testaments provide other witnesses to women’s involvement in a variety of ministries; the roles for women in the church through time have been equally as varied. Regardless of the official position of the church regarding their roles, women have remained integral to continuation of our faith. Historical restrictions on the involvement of women have been justified both scripturally and theologically; arguments supporting their involvement find the same bases. Even women who stand out in history often did not challenge the practices of their times that confined women to home, family, or the convent. For example, Hildegard of Bingen is considered a model of piety and while she demonstrated courage in her refusal to bend to the demands of clergy, she was not an advocate of change or of elevation of women’s authority in the church. Patristic attitudes have deep roots in the Judeo-Christian traditions and continue to affect contemporary avenues of ministry available to women. Barriers for women in America began falling in the nineteenth century as women moved to increasingly visible activities outside the home. However, women’s ascent into leadership roles in the church that matched the roles of men was much slower than in secular areas. -

A Survey of Leach's Petrels on Shetland in 2011

Contents Scottish Birds 32:1 (2012) 2 President’s Foreword K. Shaw PAPERS 3 The status and distribution of the Lesser Whitethroat in Dumfries & Galloway R. Mearns & B. Mearns 13 The selection of tree species by nesting Magpies in Edinburgh H.E.M. Dott 22 A survey of Leach’s Petrels on Shetland in 2011 W.T.S. Miles, R.M. Tallack, P.V. Harvey, P.M. Ellis, R. Riddington, G. Tyler, S.C. Gear, J.D. Okill, J.G Brown & N. Harper SHORT NOTES 30 Guillemot with yellow bare parts on Bass Rock J.F. Lloyd & N. Wiggin 31 Reduced breeding of Gannets on Bass Rock in 2011 J. Hunt & J.B. Nelson 32 Attempted predation of Pink-footed Geese by a Peregrine D. Hawker 32 Sparrowhawk nest predation by Carrion Crow - unique footage recorded from a nest camera M. Thornton, H. & L. Coventry 35 Black-headed Gulls eating Hawthorn berries J. Busby OBITUARIES 36 Dr Raymond Hewson D. Jenkins & A. Watson 37 Jean Murray (Jan) Donnan B. Smith ARTICLES, NEWS & VIEWS 38 Scottish seabirds - past, present and future S. Wanless & M.P. Harris 46 NEWS AND NOTICES 48 SOC SPOTLIGHT: the Fife Branch K. Dick, I.G. Cumming, P. Taylor & R. Armstrong 51 FIELD NOTE: Long-tailed Tits J. Maxwell 52 International Wader Study Group conference at Strathpeffer, September 2011 B. Kalejta Summers 54 Siskin and Skylark for company D. Watson 56 NOTES AND COMMENT 57 BOOK REVIEWS 60 RINGERS’ ROUNDUP R. Duncan 66 Twelve Mediterranean Gulls at Buckhaven, Fife on 7 September 2011 - a new Scottish record count J.S. -

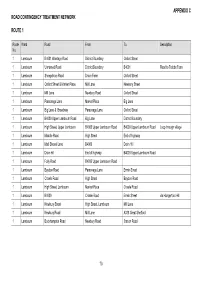

70 Appendix C Road Contingency Treatment

APPENDIX C ROAD CONTINGENCY TREATMENT NETWORK ROUTE 1 Route Ward Road From To Description No. 1 Lambourn B4001 Wantage Road District Boundary Oxford Street 1 Lambourn Unnamed Road District Boundary B4001 Road to Trabbs Farm 1 Lambourn Sheepdrove Road Drove Farm Oxford Street 1 Lambourn Oxford Street & Market Place Mill Lane Newbury Street 1 Lambourn Mill Lane Newbury Road Oxford Street 1 Lambourn Parsonage Lane Market Place Big Lane 1 Lambourn Big Lane & Broadway Parsonage Lane Oxford Street 1 Lambourn B4000 Upper Lambourn Road Big Lane District Boundary 1 Lambourn High Street, Upper Lambourn B4000 Upper Lambourn Road B4000 Upper Lambourn Road Loop through village 1 Lambourn Maddle Road High Street End of highway 1 Lambourn Malt Shovel Lane B4000 Drain Hill 1 Lambourn Drain Hill End of highway B4000 Upper Lambourn Road 1 Lambourn Folly Road B4000 Upper Lambourn Road 1 Lambourn Baydon Road Parsonage Lane Ermin Street 1 Lambourn Crowle Road High Street Baydon Road 1 Lambourn High Street, Lambourn Market Place Crowle Road 1 Lambourn B4000 Crowle Road Ermin Street via Hungerford Hill 1 Lambourn Newbury Street High Street, Lambourn Mill Lane 1 Lambourn Newbury Road Mill Lane A338 Great Shefford 1 Lambourn Bockhampton Road Newbury Road Station Road 70 APPENDIX C ROAD CONTINGENCY TREATMENT NETWORK ROUTE 1 (cont’d) Route Ward Road From To Description No. 1 Lambourn Edwards Hill Station Road High St, Lambourn 1 Lambourn Close End Edwards Hill End of highway 1 Lambourn Greenways Edwards Hill End of highway 1 Lambourn Baydon Road District Boundary A338 via Ermin Street 1 Lambourn Unnamed Road to Ramsbury Ermin Street District Boundary via Membury Industrial Estate 1 Lambourn B4001 B400 Ermin Street District Boundary 1 Lambourn, Newbury Road A338 Great Shefford Oxford Road via Boxford Kintbury & Speen 1 Kintbury High Street, Boxford Rood Hill B4000 Ermin Street 1 Speen Station Road A4 Grove Road 1 Speen Love Lane B4494 Oxford Road B4009 Long Lane 71 APPENDIX C ROAD CONTINGENCY TREATMENT NETWORK ROUTE 2 Route Ward Road From To Description No. -

The Place of the Local Preacher in Methodism

Wofford College Digital Commons @ Wofford Historical Society Addresses Methodist Collection 12-7-1909 The lP ace of the Local Preacher in Methodism Joseph B. Traywick Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wofford.edu/histaddresses Part of the Church History Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Traywick, Joseph B., "The lP ace of the Local Preacher in Methodism" (1909). Historical Society Addresses. Paper 14. http://digitalcommons.wofford.edu/histaddresses/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Methodist Collection at Digital Commons @ Wofford. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Society Addresses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Wofford. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Place of the Local Preacher in Methodism With Sketches of the Lives of Some Representative Local Preachers of the South Carolin'a Conference BY REV. JOSEPH B. TRAYWICK An Address Delivered Before the Historical Society of the South Carolina Conference, Methodist Episcopal Church, South, in Abbeville, S. C ., December 7, 1909. \ The origin of local preachers and their work in Methodi sm, like all else in that great SI)irituai awakening, was Providential. The work at the Foundry in London had been inaugurateu by Mr. Wesley for some lime. When he must needs be away for awhile. he nppoillted Thomas Maxfield. a gifted layman, to hold prayer meetings in hi s absence. But Maxfield's exhortations proved to be preaching with great effect. On Mr. Wesley's return, he was alarmed Jest he hOld gone too far; but the wise counsel of his mother served him well at thi s critical h OUT in the great movement. -

30297-Nidderdale 2012 Schedule 5:Layout 1

P R O G R A M M E (Time-table will be strictly adhered to where possible) ORDER OF JUDGING: Approx. 08.00 a.m. Breeding Hunters (commencing with Ridden Hunter Class) 09.00 a.m. Sheep Dog Trials 09.00 a.m. Carcass Class 09.00 a.m. Dogs Approx. 09.00 a.m. Riding and Turnout Approx. 09.00 a.m. Coloured Horse/Pony In-hand 09.15 a.m. Young Farmers’ Cattle 09.30 a.m. Dry Stone Walling Ballot 09.30 a.m. Beef Cattle (Local) 09.45 a.m. Sheep Approx. 10.00 a.m. All Other Cattle Judging commences Approx. 10.00 a.m. Children’s Riding Classes Approx. 10.00 a.m. Heavy Weight Agricultural Horses 10.00 a.m. Goats 10.00 a.m. Produce, Home Produce and Crafts (Benching 09.45 a.m.) 10.00 a.m. Flowers, Vegetables and Farm Crops (Benching 09.45 a.m.) 10.00 a.m. Poultry, Pigeons and Rabbits 10.30 a.m. ‘Pateley Pantry’ Stands Approx. 10.45 a.m. Mountain & Moorland 11.00 a.m. Pigs Approx. 11.00 a.m. Ridden Coloured 11.00 a.m. Trade Stands 1.15 p.m. Junior Shepherd/Shepherdess Classes (judged at the sheep pens) Approx. 2.00 p.m. Childrens’ Pet Classes (judged in the cattle rings) 2.00 p.m. Sheep - Supreme Championship MAIN RING ATTRACTIONS: 08.00-12.00 Judging - Horse and Pony classes 12.00-12.35 Inch Perfect Trials Display Team 12.35-12.55 Terrier Racing 12.55-1.30 ATV Manoeuvrability Test 1.30-2.00 Young Farmers Mascot Football 2.00-2.20 Parade of Fox Hounds by West of Yore Hunt & Claro Beagles 2.20-3.00 Inch Perfect Trials Display Team 3.00-3.30 GRAND PARADE AND PRESENTATION OF TROPHIES (Excluding Sheep, Goats, Pigs, Produce and WI) Parade of Tractors celebrating 8 decades of Nidderdale Young Farmers Club 3.30- Show Jumping OTHER ATTRACTIONS: Meltham & Meltham Mills Band playing throughout the day 12.00-12.15 St Cuthbert’s Primary School Band 12.15-1.15 Lofthouse & Middlesmoor Silver Band Forestry Exhibition Heritage Marquee Small Traders/Craft Marquee Pateley Pantry Marquee with Cookery Demonstrations 11.00 a.m. -

LINCOLNSHIRE. C.!L'stor

DIRECTORY .J LINCOLNSHIRE. C.!l'STOR. 123 Countv Court Office, His Honor Sir G. Sherslron C.AIS:l'OR REGISTRATION DISTB,ICT. Baker hart. judge) Arthur A. ~adley, registrar & Superintendent Registrar, .A.rthu:r• Angostus Padley, high bailiff; George White, acting sub-bailiff. A Union offices, Caiswr; deputy, Joseph Snrfleet.. Red court is held at the Court house every two months, house, Caisto:r . the district of which comprises the following placeB: Registrars of Births & Deaths, Caistor sub-district, Geo. -Bigby, Brocklesby~ Cabourn, Caistor,. Claxby, Abraham, Plough hill, Caistor ; deputy, Geo. White, Olixby, Croxby, Ouxwold, Grasby, .Holton-le-Moor, Caistor; Market Rasen sub-dis~rict, Frederick Wm. Keelby, Kelsey (South & North), Limber Magna, Lim Chesman, Market Rasen; deputy, Tqomas Bee, ber Parva, Nettleton, Normanby-le-Wold, Riby, Both Waterloo street, Market Ras.!lll well, Searby-with-Owmby, Somerby, Swallow, Swin Registrars of Marriages, Caistm: sub-district, Charles hope, Thoresway & ThorganbJ.. , Ainger, Market place, Oaistor;. deputy, R. H. Parker, Oaistor for bankruptcy jurisdiction is included in Lin Caistor; Market Rasen suh-di!!trict, F. W .. Chesman, coln district; Frederick Charles Brogderr, 10 Bank st. Market Rasen; deputy, Thomas Bee, Waterloo street, Lincoln,. official receiver Market Rasen County Police StatiDn, Chapel street. The whole- of the petty sessional division is under the charge of the PUBLIC OFFIQERS. police supt. of Market Rasen Customs & Excise, Harold Vale Rhodes, officer Assessor & Collector of Taxes, George White Parish Council Fire Brigade, H. Willrinson, captain Assistant Overseer, Clerk to the Parish Council & Col~ Public Hall, High street, Charles Ainger, hon. sec lector .of Rates, John Brighton, Market place. -

"I Cried out and None but Jesus Heard!" Prophetic Pedagogy

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 "I Cried Out and None but Jesus Heard!" prophetic pedagogy: the spirituality and religious lives of three nineteenth century African-American women Elecia Brown Lathon Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Lathon, Elecia Brown, ""I Cried Out and None but Jesus Heard!" prophetic pedagogy: the spirituality and religious lives of three nineteenth century African-American women" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3120. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3120 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “I CRIED OUT AND NONE BUT JESUS HEARD!” PROPHETIC PEDAGOGY THE SPIRITUALITY AND RELIGIOUS LIVES OF THREE NINETEENTH CENTURY AFRICAN-AMERICAN WOMEN A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Curriculum and Instruction By Elecia Brown Lathon B.S., Southern University, 1993 M.Ed., Louisiana State University, 1996 Ed.S., Louisiana State University, 2002 December 2005 ©Copyright 2005 Elecia Brown Lathon All Rights Reserved ii For my mother Laverne S. Brown, my inspiration, my friend and my first teacher iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS All that I am and all that I ever hope to be I owe it all to thee. -

LINCOLNSHIRE. F .Abmers-Continmd

F..AR. LINCOLNSHIRE. F .ABMERs-continmd. Mars hall John Jas.Gedney Hill, Wisbech Mastin Charles, Sutterton Fen, Boston Maplethorpe Jackson, jun. Car dyke, Marshal! John Thos. Tydd Gate, Wibbech 1Mastin Fredk. jun. Sutterton Fen, Boston Billinghay, Lincoln Marsball John Thos. Withern, Alford Mastin F. G. Kirkby Laythorpe, Sleafrd Maplethorpe Jn. Bleasby, Lrgsley, Lncln Marshall Joseph, .Aigarkirk, Boston Mastin John, Tumby, Boston Maplethorpe Jsph. Harts Grounds,Lncln Marbhall Joseph, Eagle, Lincoln Mastin William sen. Walcot Dales, Maplethorpe Wm. Harts Grounds,Lncln MarshalJJsph. The Slates,Raithby,Louth Tattershall Bridge, Linco·n Mapletoft J. Hough-on-the-Hill, Grnthm Marshall Mark,Drain side,Kirton,Boston Mastin Wm. C. Fen, Gedney, Ho"beach Mapletoft Robert, Nmmanton, Grar.thm Marshall Richard, Saxilby, Lincoln Mastin Wi!liam Cuthbert, jun. Walcot Mapletoft Wil'iam, Heckington S.O Marshall Robert, Fen, :Fleet, Holbeach Dales, Tattel"!lhall Bridge, Lincoln Mappin S. W.Manor ho. Scamp ton, Lncln Marshall Robert, Kral Coates, Spilsby Matthews James, Hallgate, Sutton St. Mapplethorpe William, Habrough S.O Marshall R. Kirkby Underwood, Bourne Edmunds, Wisbech Mapplethorpe William Newmarsh, Net- Marshal! Robert, Northorpe, Lincoln Maultby George, Rotbwell, Caistor tleton, Caistor Marshall Samuel, Hackthorn, Lincoln Maultby James, South Kelsey, Caistor March Thomas, Swinstead, Eourne Marshall Solomon, Stewton, Louth Maw Allan, Westgate, Doncaster Marfleet Mrs. Ann, Somerton castle, Marshall Mrs. S. Benington, Boston Maw Benj. Thomas, Welbourn, Lincoln Booth by, Lincoln Marshall 'fhomas, Fen,'fhorpe St.Peter, Maw Edmund Hy. Epworth, Doncaster Marfleet Charles, Boothby, Lincoln Wainfleet R.S.O Maw George, Messingham, Brigg Marfleet Edwd. Hy. Bassingbam, Lincln Marshall T. (exors. of), Ludboro', Louth Maw George, Wroot, Bawtry Marfleet Mrs.