Protection from Unjustified Premiums Hearing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2011 Annual Report Ehealth 2011 Annual Report Ehealth Is the Leading Online Source of Health Insurance for Individuals, Families and Small Businesses

Leading Online Marketplace for Health Insurance 2011 Annual Report eHealth 2011 Annual Report eHealth is the leading online source of health insurance for individuals, families and small businesses. WHO WE ARE: We are the parent company of eHealthInsurance Services, Inc., the leading online source of health insurance for individuals, families and small businesses. eHealthInsurance was founded in 1997 and our technology was responsible for the nation’s first Internet-based sale of a health insurance policy. Since its inception, the company has helped to insure over 2 million Americans. We are headquartered in Mountain View, California. WHAT WE DO: Through our technology and online marketplace, eHealth turns complex health insurance information into an objective, user-friendly format and simplifies the process for consumers to find, compare and purchase the plans that best suit their needs. We are licensed to market and sell health insurance in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. We have partnerships with more than 180 health insurance companies, and offer thousands of health insurance products online. eHealth, Inc. also provides powerful online and pharmacy-based tools to help seniors navigate Medicare health insurance options, choose the right plan and enroll in select plans online through its wholly-owned subsidiary, PlanPrescriber, Inc. (http://www.planprescriber.com) and through its Medicare website http://www.eHealthMedicare.com. eHealth sells more than health insurance: in order to cater to different customer needs, we also sell related insurance products such as dental, vision, short-term, travel, accident and critical illness insurance. All of this is complemented by a full-service customer care center of licensed and trained customer service representatives. -

Spare the Air Employer Program Members

Spare the Air Employer Program Members 511 Affymetrix Inc. 1000 Journals Project Agilent Technologies ‐ Sonoma County 3Com Corporation Public Affairs 511 Contra Costa Agnews Developmental Center 511 Regional Rideshare Program AHDD Architecture 7‐Flags Car Wash Air Products and Chemicals, Inc. A&D Christopher Ranch Air Systems Inc. A9.com Akeena Solar AB & I Akira ABA Staffing, Inc. Akraya Inc. ABB Systems Control Alameda Co. Health Care for the Homeless Abgenix, Inc. Program ABM Industries, Inc Alameda County Waste Management Auth. Above Telecommunications, Inc. Alameda Free Library Absolute Center Alameda Hospital AC Transit Alameda Unified School District Academy of Art University Alder & Colvin Academy of Chinese Culture & Health Alexa Internet Acclaim Print & Copy Centers Allergy Medical Group Of S F A Accolo Alliance Credit Union Accretive Solutions Alliance Occupational Medicine ACF Components Allied Waste Services/Republic Services Acologix Inc. Allison & Partners ACRT, Inc Alta Bates/Summit Medical Center ACS State & Local Solutions Alter Eco Act Now Alter Eco Americas Acterra ALTRANS TMA, Inc Actify, Inc. Alum Rock Library Adaptive Planning Alza Corporation Addis Creson American Century Investment Adina for Life, Inc. American International (Group) Companies Adler & Colvin American Lithographers ADP ‐ Automatic Data Processing American Lung Association Advance Design Consultants, Inc. American Musical Theatre of San Jose Advance Health Center American President Lines Ltd Advance Orthopaedics Amgen, Inc Advanced Fibre Communications Amtrak Advanced Hyperbaric Recovery of Marin Amy’s Kitchen Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. Ananda Skin Spa Advantage Sales & Marketing Anderson Zeigler Disharoon Gallagher & Advent Software, Inc Gray Aerofund Financial Svcs.,Inc. Anixter Inc. Affordable Housing Associates Anomaly Design Affymax Research Institute Anritsu Corporation Anshen + Allen, Architects BabyCenter.com Antenna Group Inc BACE Geotechnical Anza Library BackFlip APEX Wellness Bacon's Applied Biosystems BAE Systems Applied Materials, Inc. -

Sustainable Health Spending and the US Federal Budget

Sustainable Health Spending and the U.S. Federal Budget— SYMPOSIUM Washington, DC, July 24, 2012 Sustainable Health Spending Growth Relative to Growth in GDP: 2011– 2035 2.5% 1.9% 2.0% 1.5% 1.5% 1.0% 1.0% 0.5% 0.5% 0.0% -0.5% 0.0% 0.7% -1.0% - -1.5% -1.4% -2.0% 18.5% 19.5% 20.5% 21.5% 22.5% 23.5% 24.5% Federal Tax Revenues as Share of GDP *Assumes 13.1% of GDP spent on social security, defense, and other non-health Example: GDP+0 is sustainable with tax revenues at 20.5% of GDP Symposium Monograph Judith Lave, Paul Hughes-Cromwick, Thomas Getzen, eds. November 13, 2012 Contributors: Joseph Antos, Ceci Connolly, Ziad Haydar, Karen Ignagni, Joanne Kenen, David Lansky, Donald Marron, Arnold Milstein, Len Nichols, Alice Rivlin, Charles Roehrig Altarum Institute Center for Sustainable Health Spending www.altarum.org/cshs Follow us on Twitter: @ALTARUM_CSHS ALTARUM Altarum Institute Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................................ii Contributors ..........................................................................................................................................................................iii Preface .................................................................................................................................................................................viii Summary and Reflections—Thomas Getzen ........................................................................................................................x -

Spare the Air Employer Program Members List Last Updated: April

Spare the Air Employer Program Members 1000 Journals Project Affymax Research Institute 511 Contra Costa - Pleasant Hill Affymetrix Inc. 511 Contra Costa - San Pablo Agilent 511 Regional Rideshare Program Agilent Technologies - Sonoma County 7 Flags Car Wash Public Affairs A Nobel Smile Air Products and Chemicals, Inc. A&D Christopher Ranch Air Systems Inc. A. Maciel Printing Airtreks A9.com Akira AB & I Akraya Inc. ABA Staffing, Inc. Alameda Co. Health Care for the Homeless ABB Systems Control Program Abbott Alameda County Waste Management Auth. Abgenix, Inc. Alameda Free Library Able Services Alameda Hospital ABM Industries, Inc Alameda Publishing Group Above Telecommunications, Inc. Alexa Internet Absolute Center All Covered AC Transit Allergy Medical Group Of S F A Academy of Chinese Culture & Health Alliance Credit Union Acclaim Print & Copy Centers Alliance Occupational Medicine Accolo Allied Waste Services Accretive Solutions Allied Waste Services -- SCCO Division ACF Components 4915 ACRT, Inc Allied Waste Services/Republic Services ACS State & Local Solutions Allison & Partners Act Now Alta Bates/Summit Medical Center Acterra Alter Eco Actify, Inc. Alter Eco Americas Actiontec Electronics ALTRANS TMA, Inc Adaptive Planning Alum Rock Library Addis Creson AMC Entertainment, Inc Adina for Life, Inc. Amelias Antics Adler & Colvin American Century Investment Adobe Lumber American International (Group) Companies ADP - Automatic Data Processing American Lung Association in California Adura Technologies American President Lines Ltd Advance Design Consultants, Inc. Amgen, Inc Advance Health Center Amtrak Advance Orthopaedics Amy’s Kitchen Advanced Hyperbaric Recovery of Marin Anderson Zeigler Disharoon Gallagher & Advantage Sales & Marketing Gray Advent Software, Inc Andrades Automotive Aerofund Financial Svcs.,Inc. Angela Klein, Architect Affinture Anixter Inc. -

Ticker Company Domain Application Security Cubit

Cyber Security Risk Rating The Egan-Jones Cyber Security Risk Ratings helps stakeholders assess the security posture (health) of covered entities. EJPS analysts use the SecuritiesScorecard platform to ascertain the company’s Score, which is incorporated into the EJPS Proxy Research Report. The methodology utilized for determining the Score can be found at http://ejproxy.com/media/documents/Egan-Jones_Proxy_Services_Cyber_Risk_Rating.pdf. For additional questions or comments, please contact [email protected] or +1-844-495-5244 x1102. Please be aware scores posted here may be delayed. For subscription questions about the direct live feed or the full SSC report please contact [email protected]. APPLICATION CUBIT DNS ENDPOINT HACKER IP NETWORK INFORMATION PATCHING SOCIAL Minimum TICKER COMPANY DOMAIN SECURITY SCORE HEALTH SECURITY CHATTER REPUTATION SECURITY LEAK CADENCE ENGINEERING Grade Final_EJP_Rating A AGILENT TECHNOLOGIES, INC. agilent.com B A B A A A B A A A B Good AA ALCOA INC. alcoa.com D A D B A B A A A A D Some Concerns AAC americanaddictioncenters.o F B D A A A A A B A F AAC HOLDINGS INC rg Needs Attention AAL ANGLO AMERICAN PLC, LONDON angloamerican.com C A D A A A A A A A D Some Concerns AAMC ALTISOURCE ASSET MANAGEMENT B A A A A A A A A A B CORPORATION altisourceamc.com Good AAN AARON'S INC. aaronrents.com A A A A A A A A A A A Superior AAOI APPLIED OPTOELECTRONICS INC. ao-inc.com B A B A A A B A A A B Good AAT AMERICAN ASSETS TRUST INC americanassetstrust.com B A A A A A A A A A B Good AAV ADVANTAGE OIL & GAS LTD. -

Annual Report

2012 Annual Report Getting Medicare Right 2 Message From Joe Baker and Bruce Vladeck 3 Who We Are 4 Counseling & Assistance 12 Volunteers 13 Education 16 Newsletters 17 Media 19 Public Policy 22 Fiscal Year 2012 Finances 23 Our Supporters 27 Board of Directors 28 Staff A Message From: Joe Baker, President, and Bruce Vladeck, Chairman of the Board Dear Friend, You probably heard a lot about Medicare in recent months. During a busy campaign season, and leading up to the New Year, Medicare found itself squarely in the spotlight, as presidential, senatorial, and congressional candidates voiced their plans to reduce the federal deficit by cutting Medicare. Amidst these discussions about the national debt, the Medicare Rights Center strengthened its services to people with Medicare while working in Washington to protect the promise of the program—ensuring that 50 million older adults and people with disabilities have access to comprehensive and affordable health care. Medicare Rights empowers people with Medicare—and those who support them—to advocate for themselves to access quality, affordable Joe Baker and Bruce Vladeck health care. During the last fiscal year, volunteers and staff on our national Consumer and Spanish-language Helplines provided over 12,000 answers to beneficiaries with Medicare questions. By successfully processing thousands of benefits for these individuals, we secured $6.2 million in out-of-pocket savings for them, their families, and state and local governments. In addition, Medicare Rights counseled more than 2,300 professionals in 2012, each of whom went on to help multiple people with Medicare; many of these professionals came to us through our Community Partners program, which builds the capacity of New York City nonprofits to better serve their own older and disabled clients. -

Downloaded Directly from CMS Websites

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Automated Analysis of User-Generated Content on the Web Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7tt7t9t5 Author Rivas, Ryan Publication Date 2021 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Automated Analysis of User-Generated Content on the Web A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science by Ryan Rivas March 2021 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Vagelis Hristidis, Chairperson Dr. Eamonn Keogh Dr. Amr Magdy Dr. Vagelis Papalexakis Copyright by Ryan Rivas 2021 The Dissertation of Ryan Rivas is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside The text of this dissertation, in part, is a reprint of the material as it appears in the following publications: Shetty P, Rivas R, Hristidis V. Correlating ratings of health insurance plans to their providers' attributes. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2016;18(10):e279. Rivas R, Montazeri N, Le NX, Hristidis V. Automatic classification of online doctor reviews: evaluation of text classifier algorithms. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2018;20(11):e11141. Rivas R, Patil D, Hristidis V, Barr JR, Srinivasan N. The impact of colleges and hospitals to local real estate markets. Journal of Big Data. 2019 Dec 1;6(1):7. Rivas R, Sadah SA, Guo Y, Hristidis V. Classification of health-related social media posts: evaluation of post content classifier models and analysis of user demographics. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance. -

Karen Ignagni President and CEO America's Health Insurance Plans

Karen Ignagni President and CEO America’s Health Insurance Plans As President and Chief Executive Officer of America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), Karen Ignagni is the voice of health insurance plans, representing members that provide health care, long-term care, dental and disability benefits to more than 200 million Americans. AHIP was formed in late 2003 as a result of a merger between the American Association of Health Plans (AAHP) and Health Insurance Association of America (HIAA). Ms. Ignagni led AAHP and, since joining the organization in 1993, she has won many accolades for her leadership. Washingtonian named her one of the Top Three “Top Guns” of all trade association heads. Modern Healthcare magazine routinely ranks her among the 100 Most Powerful People in Healthcare. The New York Times wrote, “In a city teaming with health care lobbyists, Ms. Ignagni is widely considered one of the most effective. She blends a detailed knowledge of health policy with an intuitive feel for politics.” Fortune described the political program Ms. Ignagni spearheaded at AAHP as “worthy of a presidential election bid.” For the past several years, the Hill Newspaper has consistently ranked Ms. Ignagni among Washington’s most effective lobbyists. Ms. Ignagni regularly testifies before Congress on key federal legislation. In recent years, she has appeared before Senate and House committees on matters ranging from health insurance plans’ role in homeland security to Medicare reform to patient protection issues and access to health care coverage issues. Ms. Ignagni has authored more than 90 articles on a wide range of health care policy issues, including pieces published in The New York Times, USA Today, New York Daily News, The Washington Times, Institutional Investor, New England Journal of Medicine, Health Affairs, Modern Healthcare and Physician’s Weekly. -

Personal Finance

Personal Financial Planning for Accountants Personal Financial Planning for Accountants Copyright 2014 by DeltaCPE LLC All rights reserved. No part of this course may be reproduced in any form or by any means, without permission in writing from the publisher. The author is not engaged by this text or any accompanying lecture or electronic media in the rendering of legal, tax, accounting, or similar professional services. While the legal, tax, and accounting issues discussed in this material have been reviewed with sources believed to be reliable, concepts discussed can be affected by changes in the law or in the interpretation of such laws since this text was printed. For that reason, the accuracy and completeness of this information and the author's opinions based thereon cannot be guaranteed. In addition, state or local tax laws and procedural rules may have a material impact on the general discussion. As a result, the strategies suggested may not be suitable for every individual. Before taking any action, all references and citations should be checked and updated accordingly. This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert advice is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. —-From a Declaration of Principles jointly adopted by a committee of the American Bar Association and a Committee of Publishers and Associations. All numerical values in this course are examples subject to change. -

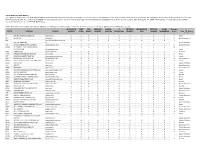

COMMONWEALTH of MASSACHUSETTS Data Breach

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS CHARLES D. BAKER MIKE KENNEALY GOVERNOR Office of Consumer Affairs and Business Regulation SECRETARY OF HOUSING AND 501 Boylston Street, Suite 5100, Boston, MA 02116 ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT KARYN E. POLITO (617) 973-8700 FAX (617) 973-8799 LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR www.mass.gov/consumer JOHN C. CHAPMAN UNDERSECRETARY Data Breach Notification Report Assigned Date Reported To OCA Organization Name Breach Type Breach Occur at MA Residents SSNBreached Account Drivers Credit Debit Provided Data Mobile Breach Description the Reporting Affected Number Licenses Numbers Credit Encrypted Device Lost Number Entity? Breached Breached Breached Monitoring Stolen 10272 1/2/2017 American Express Travel Related Electronic 11 Yes Services, Inc. 10273 1/2/2017 American Express Travel Related Electronic 213 Yes Services Company, Inc. 10274 1/3/2017 Salem Five Electronic 6 Yes 10275 1/3/2017 Eagle Bank Electronic 3 Yes 10276 1/3/2017 Bank of America Undefined Yes 2 Yes Yes Yes 10277 1/3/2017 Edgework Consulting Electronic Yes 50 Yes Yes 10533 1/3/2017 The Village Bank Electronic 1 Yes 10535 1/3/2017 The Village Bank Electronic 6 Yes 10537 1/3/2017 The Village Bank Electronic 3 Yes 10543 1/3/2017 The Village Bank Electronic 1 Yes 10544 1/4/2017 The Village Bank Electronic 3 Yes 10545 1/4/2017 The Village Bank Electronic 1 Yes 10546 1/4/2017 The Village Bank Electronic 1 Yes 10278 1/4/2017 MED-PASS Electronic Yes 1 Yes Yes 10279 1/4/2017 Webster Five Electronic 1289 Yes 10280 1/4/2017 Webster Five Electronic Yes 5 Yes Yes 10281 1/4/2017 Webster Five Electronic 28 Yes 10282 1/4/2017 American Pharmacists Electronic Yes 4 Yes Yes Association 10283 1/4/2017 Belmont Savings Bank Paper 1 Yes 10285 1/4/2017 Fidelity Investments Electronic Yes 1 Yes Yes 10286 1/5/2017 Eagle Bank Electronic 1 Yes COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS CHARLES D. -

2015 List of Businesses with Report

Entity Name "D" PLATINUM CONTRACTING SERVICES, LLC #THATZWHY LLC (2nd) Second Chance for All (H.E.L.P) Helping Earth Loving People (ieec) - FELMA.Inc 1 Campus Road Ventures L.L.C. 1 Love Auto Transport, LLC 1 P STREET NW LLC 1 Vision, INC 1,000 Days 10 FLORIDA AVE DDR LLC 10 Friends L.L.C. 100 EYE STREET ACQUISITION LLC 100 REPORTERS 100,000 Strong Foundation (The) 1000 CONNECTICUT MANAGER LLC 1000 CRANES LLC 1000 NEW JERSEY AVENUE, SE LLC 1000 VERMONT AVENUE SPE LLC 1001 CONNECTICUT LLC 1001 K INC. 1001 PENN LLC 1002 22ND STREET L.L.C. 1002 3RD STREET, SE LLC 1003 8TH STREET LLC 1005 E Street SE LLC 1008 Monroe Street NW Tenants Association of 2014 1009 NEW HAMPSHIRE LLC 101 41ST STREET, NE LLC 101 5TH ST, LLC 101 GALVESTON PLACE SW LLC 101 P STREET, SW LLC 101 PARK AVENUE PARTNERS, Inc. 1010 25th St 107 LLC 1010 25TH STREET LLC 1010 IRVING, LLC 1010 V LLC 1010 VERMONT AVENUE SPE LLC 1010 WISCONSIN LLC 1011 NEW HAMPSHIRE AVENUE LLC 1012 ADAMS LLC 1012 INC. 1013 E Street LLC 1013 U STREET LLC 1013-1015 KENILWORTH AVENUE LLC 1014 10th LLC 1015 15TH STREET, Inc. 1016 FIRST STREET LLC 1018 Florida Avenue Condominium LLC 102 O STREET, SW LLC 1020 16TH STREET, N.W. HOLDINGS LLC 1021 EUCLID ST NW LLC 1021 NEW JERSEY AVENUE LLC 1023 46th Street LLC 1025 POTOMAC STREET LLC 1025 VERMONT AVENUE, LLC 1026 Investments, LLC 1030 PARK RD LLC 1030 PERRY STREET LLC 1031 4TH STREET, LLC 1032 BLADENSBURG NE AMDC, LLC 104 O STREET, SW LLC 104 RHODE ISLAND AVENUE, N.W. -

Fall 2012 NAMD Conference

2012 CONFERENCERENC PROGRAM Fall 2012 NAMD Conference OCTOBER 28–30, 2012 ★ MARRIOTT CRYSTAL GATEWAY ★ ARLINGTON, VA WWW.MEDICAIDDIRECTORS.ORG CONTENTS AD INDEX AmeriHealth Mercy Family of GENERAL INFO Companies ...............................................2 Molina Healthcare, Inc. .....................4 & 6 NACDS .........................................................9 Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. ........... 16 Noridian Health Care Solutions ..............18 Fall 2012 MAXIMUS ................................................... 19 Navigant Healthcare ............................... 20 CVS Caremark ..........................................25 NAMD Wellpoint ...................................................37 UnitedHealthcare Community & State ................................................... 40 Conference Golden Living ...........................................42 Aetna Medicaid ....................................... 44 OCTOBER 28–30, 2012 PhRMA .......................................................47 MARRIOTT CRYSTAL GATEWAY Qualis Health ............................................49 ARLINGTON, VA BerryDunn ................................................ 50 Sellers Dorsey ...........................................52 Roche .........................................................53 Amerigroup Corporation ........................54 Medicaid Learning Center ......................56 LexisNexis..................................................57 HP ...............................................................58 ACS CAN ..................................................