Exhibition Brochure, Robert Whitman, Playback.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modernism 1 Modernism

Modernism 1 Modernism Modernism, in its broadest definition, is modern thought, character, or practice. More specifically, the term describes the modernist movement, its set of cultural tendencies and array of associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Modernism was a revolt against the conservative values of realism.[2] [3] [4] Arguably the most paradigmatic motive of modernism is the rejection of tradition and its reprise, incorporation, rewriting, recapitulation, revision and parody in new forms.[5] [6] [7] Modernism rejected the lingering certainty of Enlightenment thinking and also rejected the existence of a compassionate, all-powerful Creator God.[8] [9] In general, the term modernism encompasses the activities and output of those who felt the "traditional" forms of art, architecture, literature, religious faith, social organization and daily life were becoming outdated in the new economic, social, and political conditions of an Hans Hofmann, "The Gate", 1959–1960, emerging fully industrialized world. The poet Ezra Pound's 1934 collection: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. injunction to "Make it new!" was paradigmatic of the movement's Hofmann was renowned not only as an artist but approach towards the obsolete. Another paradigmatic exhortation was also as a teacher of art, and a modernist theorist articulated by philosopher and composer Theodor Adorno, who, in the both in his native Germany and later in the U.S. During the 1930s in New York and California he 1940s, challenged conventional surface coherence and appearance of introduced modernism and modernist theories to [10] harmony typical of the rationality of Enlightenment thinking. -

Press Release E.A.T.—Experiments in Art and Technology

Press Release E.A.T.—Experiments in Art and Technology July 25–November 1, 2015 Mönchsberg [3] & [4] The Museum der Moderne Salzburg presents an international premiere: a Presse comprehensive survey of the groundbreaking projects of E.A.T.—Experiments Mönchsberg 32 in Art and Technology, an evolving association of artists and technologists 5020 Salzburg who wrote history in the 1960s and 1970s with projects between New York and Austria Osaka. The show is on view on the Mönchsberg. T +43 662 842220-601 F +43 662 842220-700 Salzburg, July 24, 2015. The Museum der Moderne Salzburg mounts the first-ever comprehensive retrospective of the activities of Experiments in Art and Technology [email protected] www.museumdermoderne.at (E.A.T.), a unique association of engineers and artists who wrote history in the 1960s and 1970s. Artists like Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008) and Robert Whitman (b. 1935) teamed up with Billy Klüver (1927–2004), a visionary technologist at Bell Telephone Laboratories, and his colleague Fred Waldhauer (1927–1993) to launch a groundbreaking initiative that would realize works of art in an unprecedented collaborative effort. The Museum der Moderne Salzburg dedicates two levels of its temporary exhibition galleries on the Mönchsberg with over 16,000 sq ft of floor space to this seminal venture fusing art and technology; around two hundred works of art and projects ranging from kinetic objects, installations, and performances to films, videos, and photographs as well as drawings and prints exemplify the most important stages of E.A.T.’s evolution. “In the past smaller exhibitions have highlighted the best-known events in E.A.T.’s history, but a comprehensive panorama of the group’s activities that reveals the full range and diversity of E.A.T.’s output has long been overdue. -

Big in Japan at the 1970 World’S Fair by W

PROOF1 2/6/20 @ 6pm BN / MM Please return to: by BIG IN JAPAN 40 | MAR 2020 MAR | SPECTRUM.IEEE.ORG AT THE 1970 WORLD’S FAIR FAIR WORLD’S 1970 THE AT HOW ART, TECH, AND PEPSICO THEN CLASHED TECH, COLLABORATED, ART, HOW BY W. PATRICK M PATRICK W. BY CRAY c SPECTRUM.IEEE.ORG | MAR 2020 MAR | 41 PHOTOGRAPH BY Firstname Lastname RK MM BP EV GZ AN DAS EG ES HG JK MEK PER SKM SAC TSP WJ EAB SH JNL MK (PDF) (PDF) (PDF) (PDF) (PDF) (PDF) (PDF) Big in Japan I. The Fog and The Floats ON 18 MARCH 1970, a former Japanese princess stood at the tion. To that end, Pepsi directed close to center of a cavernous domed structure on the outskirts of Osaka. US $2 million (over $13 million today) to With a small crowd of dignitaries, artists, engineers, and busi- E.A.T. to create the biggest, most elaborate, ness executives looking on, she gracefully cut a ribbon that teth- and most expensive art project of its time. ered a large red balloon to a ceremonial Shinto altar. Rumbles of Perhaps it was inevitable, but over the thunder rolled out from speakers hidden in the ceiling. As the 18 months it took E.A.T. to design and balloon slowly floated upward, it appeared to meet itself in mid- build the pavilion, Pepsi executives grew air, reflecting off the massive spherical mirror that covered the increasingly concerned about the group’s walls and ceiling. vision. And just a month after the opening, With that, one of the world’s most extravagant and expensive the partnership collapsed amidst a flurry multimedia installations officially opened, and the attendees of recriminating letters and legal threats. -

The Art of Performance a Critical Anthology

THE ART OF PERFORMANCE A CRITICAL ANTHOLOGY edited by GREGORY BATTCOCK AND ROBERT NICKAS /ubu editions 2010 The Art of Performance A Critical Anthology 1984 Edited By: Gregory Battcock and Robert Nickas /ubueditions ubu.com/ubu This UbuWeb Edition edited by Lucia della Paolera 2010 2 The original edition was published by E.P. DUTTON, INC. NEW YORK For G. B. Copyright @ 1984 by the Estate of Gregory Battcock and Robert Nickas All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper or broadcast. Published in the United States by E. P. Dutton, Inc., 2 Park Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10016 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 79-53323 ISBN: 0-525-48039-0 Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Toronto 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition Vito Acconci: "Notebook: On Activity and Performance." Reprinted from Art and Artists 6, no. 2 (May l97l), pp. 68-69, by permission of Art and Artists and the author. Russell Baker: "Observer: Seated One Day At the Cello." Reprinted from The New York Times, May 14, 1967, p. lOE, by permission of The New York Times. Copyright @ 1967 by The New York Times Company. -

The Museum of Modern Art: the Mainstream Assimilating New Art

AWAY FROM THE MAINSTREAM: THREE ALTERNATIVE SPACES IN NEW YORK AND THE EXPANSION OF ART IN THE 1970s By IM SUE LEE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Im Sue Lee 2 To mom 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply grateful to my committee, Joyce Tsai, Melissa Hyde, Guolong Lai, and Phillip Wegner, for their constant, generous, and inspiring support. Joyce Tsai encouraged me to keep working on my dissertation project and guided me in the right direction. Mellissa Hyde and Guolong Lai gave me administrative support as well as intellectual guidance throughout the coursework and the research phase. Phillip Wegner inspired me with his deep understanding of critical theories. I also want to thank Alexander Alberro and Shepherd Steiner, who gave their precious advice when this project began. My thanks also go to Maureen Turim for her inspiring advice and intellectual stimuli. Thanks are also due to the librarians and archivists of art resources I consulted for this project: Jennifer Tobias at the Museum Library of MoMA, Michelle Harvey at the Museum Archive of MoMA, Marisa Bourgoin at Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art, Elizabeth Hirsch at Artists Space, John Migliore at The Kitchen, Holly Stanton at Electronic Arts Intermix, and Amie Scally and Sean Keenan at White Columns. They helped me to access the resources and to publish the archival materials in my dissertation. I also wish to thank Lucy Lippard for her response to my questions. -

EXPERIMENTS in ART and TECHNOLOGY a Brief History and Summary of Major Projects 1966 - 1998

EXPERIMENTS IN ART AND TECHNOLOGY A Brief History and Summary of Major Projects 1966 - 1998 Experiments In Art And Technology 69 Appletree Row Berkeley Heights, NJ 07922 March 1, 1998 MAINTAIN A CONSTRUCTIVE CLIMATE FOR THE RECOGNITION OF THE NEW . TECHNOLOGY AND THE ARTS B Y A CIVILIZED COLLABORATION BETWEEN GROUPS UNREALISTICALLY DEVELOP- ING IN ISOLATION . ELIMINATE TAE SEPARATION OF THE INDIVIDUAL FROM TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE AND EKPAND AND ENRICH TECHNOLOGY TO GIVE 'II0 INDIVIDUAL VARIETY, PLEASURE AND AVENUES FOR EXPLORATION AND IN- VOLVEMENT IN CONTEMPORARY LIFE* ENCOURAGE INDUSTRIAL INITIATIVE IN GENERATING ORIGINAL FORETHOUGHT, INSTEAD OF A COMPROMISE IN AFTER- , M A T H, AND PRECIPITATE A MUTUAL AGREEMENT IN , ORDER TO AVOID THE WASTE OF A CULTURAL REVOLUTION . EXPERIMENTS IN ART AND TECHNOLOGY BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF E .A .T . in 1966 by Billy in Art and Technology was founded Experiments Fred Waldhauer, and Robert Whitman . Kluver, Robert Rauschenberg, developed the not-for-profit organization The decision to form and Engineering," the experience of "9 Evenings : Theatre from Armory in New York City in October 1966 held at the 69th Regiment artists worked .engineers and ten contemporary where''forty It became clear that if continuing together on the performances . achieved, a artist-engineer relationships were to be organic made to set up the necessary major organized effort had to be physical and social conditions . was held in New York City, November 1966, a meeting of artists . In engineers and other interested people attended by 300 artists, providing the was positive to the idea of E .A .T . The reaction . Robert Rauschenberg with access to the technical world artists president, Robert Whitman became chairman, Billy Kluver was opened to Fred Waldhauer secretary . -

1000 Words: Robert Whitman Talks About Passport 2011

FOR MORE THAN FIFTY YEARS, Robert Whitman has been making theater pieces Indeed, Whitman is fascinated by events that can never be grasped in their that verge on alchemy. In these works, everyday objects take on uncanny properties, entirety but may be experienced intensely from particular points of view—a as in Two Holes of Water No. 3, 1966, where suburban station wagons wrapped preoccupation evident in such works as American Moon, 1960, where he dis in plastic become mobile TV and film projectors, or inPrune Flat, 1965, in which tributed audience members into partitioned “tunnels,” and Local Report, 2005, a single lightbulb descends from above, its brightness washing out the piece’s for which participants in five locations in four states provided video “news projected 16mm footage and restoring threedimensionality to the world onstage. reports” via their cell phones; for the latter work, the artist mixed video and sound In the 1960s, when many artists sought to escape metaphor and illusion, Whitman reports at the performance site while streaming them online. This piece, in turn, embraced them, even using stageshow tricks—mirrors, transparent scrims, shadow is part of a series of similar events dating back to works such as NEWS, 1972, play, and moving props—that hark back to vaudeville and magic lanterns. when Whitman used pay phones to transmit farflung dispatches, and radio Whitman is also celebrated for his pioneering collaborations with engineers waves to broadcast them. and scientists, the most famous of these being the many projects he undertook Whitman’s new work, Passport, is the latest exploration of this spatial disper with visionary engineer Billy Klüver. -

Notices of the American Mathematical Society

OF THE 1994 AMS Election Special Section page 7 4 7 Fields Medals and Nevanlinna Prize Awarded at ICM-94 page 763 SEPTEMBER 1994, VOLUME 41, NUMBER 7 Providence, Rhode Island, USA ISSN 0002-9920 Calendar of AMS Meetings and Conferences This calendar lists all meetings and conferences approved prior to the date this issue insofar as is possible. Instructions for submission of abstracts can be found in the went to press. The summer and annual meetings are joint meetings with the Mathe· January 1994 issue of the Notices on page 43. Abstracts of papers to be presented at matical Association of America. the meeting must be received at the headquarters of the Society in Providence, Rhode Abstracts of papers presented at a meeting of the Society are published in the Island, on or before the deadline given below for the meeting. Note that the deadline for journal Abstracts of papers presented to the American Mathematical Society in the abstracts for consideration for presentation at special sessions is usually three weeks issue corresponding to that of the Notices which contains the program of the meeting, earlier than that specified below. Meetings Abstract Program Meeting# Date Place Deadline Issue 895 t October 28-29, 1994 Stillwater, Oklahoma Expired October 896 t November 11-13, 1994 Richmond, Virginia Expired October 897 * January 4-7, 1995 (101st Annual Meeting) San Francisco, California October 3 January 898 * March 4-5, 1995 Hartford, Connecticut December 1 March 899 * March 17-18, 1995 Orlando, Florida December 1 March 900 * March 24-25, -

Guggenheim Museum Archives Reel-To-Reel Collection “Post Object Sculpture” with Jack Burnham, 1967 Good Afternoon, Ladies An

Guggenheim Museum Archives Reel-to-Reel collection “Post Object Sculpture” with Jack Burnham, 1967 MALE 1 Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to the third in a series of lectures on contemporary sculpture, presented by the museum on the occasion of the Fifth Guggenheim International Exhibition. Today’s lecture is by Mr. Jack Wesley Burnham. Mr. Burnham is an individual who combines the extraordinary qualities of being both artist and scientist, as well as writer. He was born in 1931 in New York City. He studied at the Boston Museum School, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He holds an engineering degree. He holds the degrees of Bachelor of Fine Arts and Master of Fine Arts from Yale University, at which institution he was on the faculty. [00:01:00] And he’s at present a professor at Northwestern University. He is the author of a major new study of modern sculpture, to be published next year by Braziller in New York, entitled Beyond Modern Sculpture. His lecture today is entitled, “Post-Object Sculpture.” After the lecture, there will be a short question-and-answer period. Mr. Burnham. JACK BURNHAM Mr. [Fry?], I’d like to thank you for inviting me. And I’d like to [00:02:00] thank all of you for being here today. I’m going to read part of this lecture, and part of it will be fairly extemporaneous. But I’d like to begin by saying that I find the task of speaking on post- object sculpture difficult for two reasons. First, because the rationale behind object sculpture and the art form itself have developed to such a sophisticated degree in the past two years. -

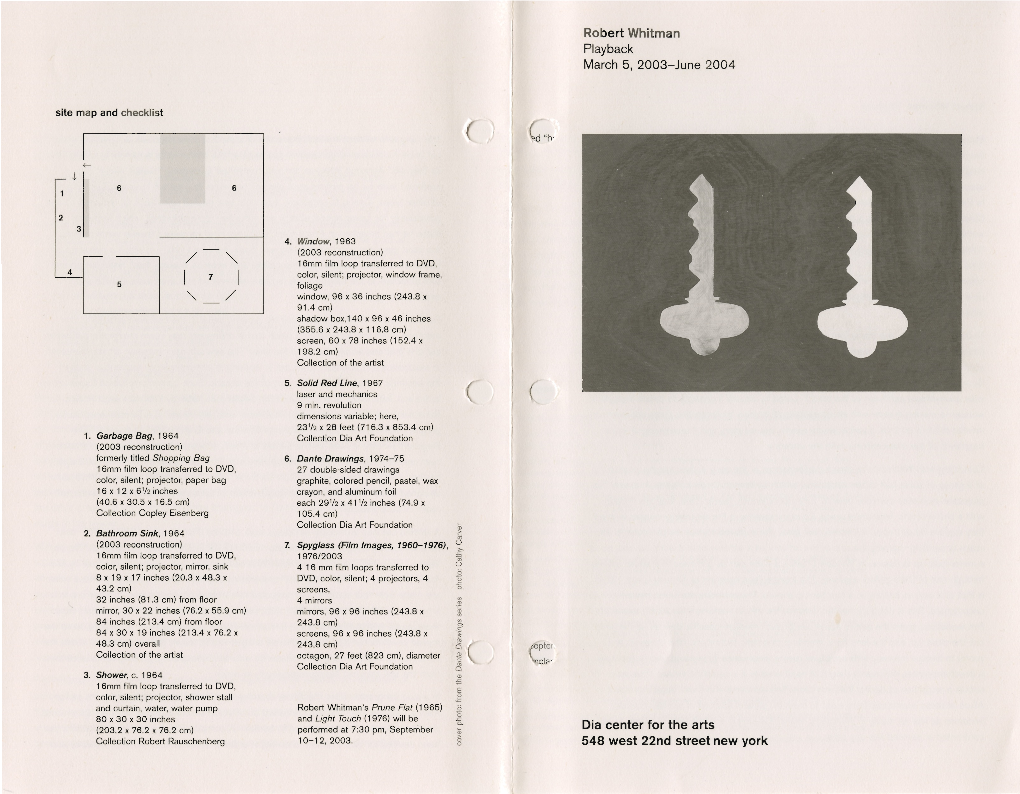

Brochure, Robert Whitman, Prune Flat, Light Touch.Pdf

Robert Whitman Prune Flat (1965) Light Touch (1976) Robert Whitman was born in New York City in 1935. He studied literature at Rutgers , The State University of New Jersey, from 1953 to 1957, and art history at Columbia University in 1958 . In the late fifties he began to present performances , including the pioneering works American Moon (1960) and Prune Flat (1965), as well as to exhibit his multimedia work in some of New York's more influential experimental venues, such as the Hansa, Reuben, and Martha Jackson galleries . With scientists Billy Kluver and Fred Waldhauer and artist Robert Rauschenberg, Whitman cofounded , in 1966, Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), a loose-knit association that organized collaborations between artists and scientists . His one-person exhibitions were held at such venues as the Jewish Museum, New York (1968) , the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago (1968), and the Museum of Modern Art , New York (1973). Dia organized a retrospective of his theater works in 1976 . Several theater projects have also toured to various European venues, including the Moderna Museet, Stockholm (1987 and 1989) , and the Centre Pompidou, Paris (2001 and 2002). selected bibliography La Prade, Erik. "The Seeing Word : An Interview with Robert Whitman: • Brooklyn Rail (June-July 2003). Robert Whitman: Playback. New York: Dia Art Foundation, 2003 . Texts by George Baker, Lynne Cooke , David Joselit, Ben Portis, and Robert Whitman . Off Limits: Rutgers University and the Avant-Garde, 1957-1963. Ed. Joan Marter. New Brunswick , N.J.: Rutgers University Press, in association with Newark Museum, Newark, N.J., 1999. Interview by Joseph Jacobs, pp . -

Art History 1

Art History 1 ART HISTORY Professors Farès El-Dahdah Contact Information Joseph Manca Art History Associate Professors https://arthistory.rice.edu/ Graham Bader 103 Herring Hall Leo Costello 713-348-4276 Gordon Hughes Graham Bader Fabiola López-Durán Department Chair Lida Oukaderova [email protected] Assistant Professors Sophie Crawford-Brown The Department of Art History offers a wide range of courses in Farshid Emami European, American, Latin American, Middle Eastern/Islamic, African/ Olivia Young African diaspora and Asian art history. The major in Art History is For Rice University degree-granting programs: structured to expose students to the chronological, geographical, and To view the list of official course offerings, please see Rice’s methodological breadth of the field of scholarship. Students in the Course Catalog (https://courses.rice.edu/admweb/!SWKSCAT.cat? program may pursue the BA degree with a major in Art History. The p_action=cata) department also offers a minor in Art History. To view the most recent semester’s course schedule, please see Rice's Bachelor's Program Course Schedule (https://courses.rice.edu/admweb/!SWKSCAT.cat) • Bachelor of Arts (BA) Degree with a Major in Art History (https:// Art History (HART) ga.rice.edu/programs-study/departments-programs/humanities/art- HART 100 - AP/OTH CREDIT IN ART HISTORY history/art-history-ba/) Short Title: AP/OTH CREDIT IN ART HISTORY Department: Art History Minor Grade Mode: Standard Letter Course Type: Transfer • Minor in Cinema and Media Studies (https://ga.rice.edu/programs- Credit Hours: 3 study/departments-programs/humanities/cinema-media-studies/ Restrictions: Enrollment is limited to Undergraduate, Undergraduate cinema-media-studies-minor/) Professional or Visiting Undergraduate level students. -

"The Line Between the Happening and Daily Life Should Be Kept As Fluid, and Perhaps Indistinct, As Possible."

"The line between the Happening and daily life should be kept as fluid, and perhaps indistinct, as possible." Synopsis What began as a challenge to the category of "art" initiated by the Futurists and Dadaists in the 1910s and 1920s came to fruition with the performance art movements, one branch of which was referred to as Happenings. Happenings involved more than the detached observation of the viewer; the artist engaged with Happenings required the viewer to actively participate in each piece. There was not a definite or consistent style for Happenings, as they greatly varied in size and intricacy. However, all artists staging Happenings operated with the fundamental belief that art could be brought into the realm of everyday life. This turn toward performance was a reaction against the long- standing dominance of the technical aesthetics of Abstract Expressionism and was a new art form that grew out of the social changes occurring in the 1950s and 1960s. © The Art Story Foundation – All rights Reserved For more movements, artists and ideas on Modern Art visit www.TheArtStory.org Key Ideas A main component of Happenings was the involvement of the viewer. Each instance a Happening occurred the viewer was used to add in an element of chance so, every time a piece was performed or exhibited it would never be the same as the previous time. Unlike preceding works of art which were, by definition, static, Happenings could evolve and provide a unique encounter for each individual who partook of the experience. The concept of the ephemeral was important to Happenings, as the performance was a temporary experience, and, as such could not be exhibited in a museum in the traditional sense.