BT Response to Ofcom's Consultation on Promoting Competition And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virgin Media Welcomes the Opportunity to Participate in the Debate on the Future of Public Service Media (‘PSM’) in the UK

Non-Confidential Small Screen: Big Debate Consultation The Future of Public Service Media Summary Virgin Media welcomes the opportunity to participate in the debate on the future of public service media (‘PSM’) in the UK. Our contribution stems not only from our position as a pay-TV service provider, but also draws on our experience in the telecommunications market more broadly as some of the changes happening in the connectivity space will fuel the adoption of new ways of consuming content. We have played, and will continue to play, a leading role in the digitisation of the UK market. Since 2013 when Virgin Media was acquired by Liberty Global plc, we have spent more than £8.7bn on upgrading and expanding Virgin Media’s network, extending it to an additional 2.4 million premises to cover more than half the country – more than all of the alternative providers combined. We are also upgrading our network to bring next-generation gigabit broadband to our entire UK footprint by the end of 2021 – a pace unmatched by anyone else. We, together with our parent company Liberty Global, are a strong believer in the benefits of the fixed-mobile convergence (FMC) and are on a path to become a converged provider pending a regulatory approval of our Virgin Media / O2 joint venture. We expect the new joint venture to be able to deliver £10bn investment in the UK’s broadband network over the next five years, expand 5G and build to additional premises. The joint venture, and the associated investments, will accelerate the availability and take up of FMC propositions in the UK. -

These Listing Particulars Have Been Prepared Solely

THESE LISTING PARTICULARS HAVE BEEN PREPARED SOLELY FOR THE PURPOSES OF ADMITTING THE NOTES TO THE OFFICIAL LIST AND TRADING ON THE GLOBAL EXCHANGE MARKET OF EURONEXT DUBLIN LISTING MEMORANDUM Virgin Media Vendor financing Notes IV Designated Activity Company $500,000,000 5.000% Vendor Financing Notes due 2028 September 15, 2020 Application has been made to the Irish Stock Exchange PLC trading as Euronext Dublin ("Euronext Dublin") for the $500,000,000 5.000% Vendor Financing Notes due 2028 (the “Notes”) issued by Virgin Media Vendor Financing Notes IV Designated Activity Company (formerly Dolya Holdco 18 Designated Activity Company) (the "Issuer") to be admitted to its Official List and to trading on the Global Exchange Market. The Notes were issued pursuant to the trust deed dated as of June 24, 2020 (the “Trust Deed”), between, among others, the Issuer, as issuer, BNY Mellon Corporate Trustee Services Limited, as notes trustee (the “Notes Trustee”) and BNY Mellon Corporate Trustee Services Limited, as security trustee (the “Security Trustee”). Except as otherwise provided in the Trust Deed, the Notes will be treated as one single class for all purposes under the Indenture including, without limitation, waivers, amendments, redemptions and offers to purchase. This Listing Memorandum together with the Offering Circular dated June 10, 2020 (the “Offering Circular”) which is attached hereto as Annex A, constitutes listing particulars (the “Listing Particulars”) for the purposes of admitting the Notes to Euronext Dublin’s Official List and to trading on its Global Exchange Market and has been approved by Euronext Dublin. Any capitalized term used herein, but not otherwise defined or referenced in this Listing Memorandum, shall have the meaning ascribed to such term in the Offering Circular. -

July Scorecard

RootMetrics July 5G scorecard A look at 5G performance in Leicester, Liverpool, Manchester, and Newcastle 5G in the UK is growing fast. To provide the best view of the consumer’s real-world 5G experience, our new 5G Scorecards look at both 5G-only and 5G mixed mode results and combine those into one view of Everyday 5G performance. Our July 5G Scorecard looks at Everyday 5G availability and speed results from our first-half 2021 testing in Leicester, Liverpool, Manchester, and Newcastle. For added context, the maps below also show 5G-only results and overall median download speeds recorded on all network technologies. To learn more about Everyday 5G results, see below or read our new blog. To see more 5G results, visit our May and June 5G Scorecards. High-level storylines EE posted the highest Everyday 5G O2 (now Virgin Media O2) clocked availability in all four cities (including a tie the fastest Everyday 5G median download with Vodafone in Liverpool), along with speed in all four cities, topping out at a consistently fast Everyday 5G median speedy 153.4 Mbps in Leicester. While O2’s download speeds. EE also registered Everyday 5G availability wasn’t as improved Everyday 5G availability in all widespread as that of most operators, it four cities since 2H 2020, with faster showed nice improvement in each city Everyday 5G speeds in three of those cities. since 2H 2020. Three showed good progress in 1H 2021, Vodafone didn’t register any 5G increasing its Everyday 5G availability in all results in Leicester, but the operator had four cities since 2H 2020 and delivering fast Everyday 5G median download faster speeds in three cities. -

$750,000,000 51/2% Senior Secured Notes Due 2026 Issued by Virgin

LISTING PARTICULARS 1 $750,000,000 5 /2% Senior Secured Notes due 2026 issued by Virgin Media Secured Finance PLC Virgin Media Secured Finance PLC (“Virgin Media Secured Finance” or the “Issuer”) offered $750,000,000 aggregate 1 principal amount of its 5 /2% Senior Secured Notes due 2026 (the “Notes”). The Notes bear interest at a rate of 5.5% per annum. The Notes mature on August 15, 2026. Interest on the Notes is payable semi- annually on each February 15 and August 15, beginning on February 15, 2017. Some or all of the Notes may be redeemed at any time prior to August 15, 2021 at a price equal to 100% of the principal amount of the Notes redeemed plus accrued and unpaid interest to (but excluding) the redemption date and a “make-whole” premium, as described elsewhere in these listing particulars (the “listing particulars”). The Notes may be redeemed at any time on or after August 15, 2021 at the redemption prices set forth elsewhere in these listing particulars. In addition, at any time prior to August 15, 2019 we may redeem up to 40% of the applicable Notes with the net proceeds of one or more specified equity offerings at the redemption prices set forth elsewhere in these listing particulars. Prior to August 15, 2021, during each 12-month period commencing on the Issue Date (as defined below), up to 10% of the principal amount of the Notes may be redeemed at a redemption price equal to 103% of the principal amount thereof plus accrued and unpaid interest to (but excluding) the redemption date. -

February 16, 2021 “SAFE HARBOR” Associated with Network Expansions; Other Factors Detailed from Time to Time in Our Filings with the U.S

February 16, 2021 “SAFE HARBOR” associated with network expansions; other factors detailed from time to time in our filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Forward-Looking Statements + Disclaimer Commission; and management’s response to any of the aforementioned factors. For additional information on identifying factors This presentation contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995. In that may cause actual results to vary materially from those stated in forward-looking statements, please see our filings with the U.S. this context, forward-looking statements often address expected future business and financial performance and financial condition, Securities and Exchange Commission, including our most recently filed Form 10-K. These forward-looking statements speak only as of and often contain words such as “expect,” “anticipate,” “intend,” “plan,” “believe,” “seek,” “see,” “will,” “would,” “may,” “target,” and the date of this release. We expressly disclaim any obligation or undertaking to disseminate any updates or revisions to any forward- similar expressions and variations or negatives of these words. These forward-looking statements may include, among other things, looking statement contained herein to reflect any change in our expectations with regard thereto or any change in events, conditions statements with respect to our strategies and priorities, future growth prospects and opportunities, results of operations, uses of or circumstances on which any such statement -

Q2 2021 Earnings Release

Virgin Media O2 Reports Preliminary Q2 2021 Results • Supercharging convergence growth with the launch of Virgin Media O2 • Strong Q2 adds and pro forma transaction adjusted EBITDA +6% YoY • Merger synergies have been validated and the integration is underway • Solid capital structure supported by our first ever Green Bond issue VMED O2 UK Limited (Virgin Media O2) is an integrated communications provider in the U.K., delivering connectivity and entertainment services to 5.7 million fixed-line customers and to 41.0 million retail and wholesale mobile connections as of 30 June 2021. In addition, it provides business communication products and services to small, medium and large enterprise and public sector customers as well as wholesale services to other operators and partners. Formed on 1 June 2021, Virgin Media O2 is a 50:50 joint venture between Liberty Global plc (Liberty Global) and Telefónica, SA (Telefónica). This release includes the actual IFRS results for Virgin Media O2 from launch, as well as pro forma1 results for the company as though the joint venture was created on 1 January 2020. The commentary in this release is based on a discussion of pro forma results. Lutz Schüler, CEO of Virgin Media O2, commented: “Virgin Media O2 is off to a flying start. We’ve maintained the strong momentum of recent quarters and are one of the largest and fastest growing converged providers. Our mission is to upgrade the UK, and we are doing exactly that. Today we’ve announced a major new fibre upgrade programme which will see us begin the next evolution of our network, building on the investment, firepower and leadership we already have and ensuring we’re fibre fit for the future. -

BT Group Regulatory Affairs, Response Remove All 4

BT response to Ofcom’s consultation on promoting competition and investment in fibre networks - Wholesale Fixed Telecoms Market Review 2021-26 13 May 2020 Non-confidential version Branding: only keep logos if the response is on behalf of more than one brand, i.e. BT/Openreach joint response or BT/EE/Plusnet joint response. Comments should be addressed to: Remove the other brands, or if it is purely a BT BT Group Regulatory Affairs, response remove all 4. BT Centre, London, EC1A 7AJ [email protected] BT RESPONSE TO OFCOM’S CONSULTATION ON COMPETITION AND INVESTMENT IN FIBRE NETWORKS 2 Contents1 CONTENTS ....................................................................................................................................................... 2 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................................ 3 2. OFCOM'S MARKET ANALYSIS SHOULD BETTER REFLECT FORWARD-LOOKING COMPETITION .................. 10 OPENREACH FACES STRONG FORWARD-LOOKING WHOLESALE COMPETITION IN WLA MARKETS WHICH BENEFITS CONSUMERS .... 11 OFCOM SHOULD REVISIT ITS PROPOSED MARKET DEFINITION .......................................................................................... 19 OPENREACH DOES NOT HAVE SMP IN ULTRAFAST CAPABLE LINES NATIONALLY NOR FORWARD-LOOKING SMP AT ANY SPEEDS IN VIRGIN MEDIA AREAS ............................................................................................................................................. 22 LEASED LINES -

Liberty Global Annual Report 2021

Liberty Global Annual Report 2021 Form 10-K (NASDAQ:LBTYK) Published: March 30th, 2021 PDF generated by stocklight.com UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K/A (Amendment No. 1) ☑ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2020 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission file number 001-35961 Liberty Global plc (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) England and Wales 98-1112770 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) Griffin House 161 Hammersmith Rd London United Kingdom W6 8BS (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: +44.208.483.6449 or 303.220.6600 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered Class A ordinary shares LBTYA Nasdaq Global Select Market Class B ordinary shares LBTYB Nasdaq Global Select Market Class C ordinary shares LBTYK Nasdaq Global Select Market Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: none Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☑ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the Registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. -

O2, Virgin Media to Merge Into £38-Bn UK Telco Giant 7 May 2020, by Emmanuelle Michel

O2, Virgin Media to merge into £38-bn UK telco giant 7 May 2020, by Emmanuelle Michel Pallete said the merger would create "the leading operator in the United Kingdom" that would be "a game-changer" in the British telecoms sector. "We are creating a strong competitor with significant scale and financial strength to invest in UK digital infrastructure and give millions of consumers, business and public sector customers more choice and value." O2 is one of the few operators to have its own wireless network in the UK where it has 34 million mobile customers and access to several million via virtual operators like Tesco Mobile that use the O2 network. Rivals no more Virgin Media, which was purchased in 2013 by Liberty Global, the Colorado-based cable giant controlled by US tycoon John Malone, counts six Telefonica and Liberty Global on Thursday said million cable subscribers and 3.3 million mobile they would merge their UK units O2 and Virgin customers. Media to create a £38-billion telecoms giant that could shake up the British market. Alvarez-Pallete said it was Telefonica's "biggest- ever deal". The mega-deal is the biggest tie-up to be unveiled since the coronavirus pandemic hit home in March, He said it had "not yet been decided" who would sending most of the planet into lockdown and head the new company with the management to be dealing a major blow to the global economy. chose by the time the deal closes in mid-2021. Until now, O2, which is owned by Spain's 'Strong competitor for BT' Telefonica, and Virgin Media, which is owned by US cable giant Liberty Global, have been rivals. -

A Note About Everyday 5G Results

RootMetrics June 5G scorecard A look at 5G performance in Cardiff, Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Nottingham 5G in the UK is growing fast. To provide the best view of the consumer’s real-world 5G experience, our new 5G Scorecard looks at both 5G-only and 5G mixed mode results and combines those into one view of Everyday 5G performance. Our June 5G Scorecard looks at Everyday 5G availability and speed results from our first-half 2021 testing in Cardiff, Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Nottingham. For additional performance context, the maps below also show 5G-only results and overall median download speeds recorded on all network technologies. To learn more about Everyday 5G results, see below or read our new blog. To see more 5G performance results, visit our May 5G Scorecard. High-level storylines EE posted the highest Everyday 5G O2 (now Virgin Media O2) clocked availability in all four cities, along with the the fastest Everyday 5G median download fastest Everyday 5G median download speed in Edinburgh, and its speeds were speed in Nottingham. EE also had improved impressive elsewhere. O2 also showed an Everyday 5G availability in three out of four expanded 5G footprint since 2H 2020, cities since 2H 2020 and faster Everyday 5G registering 5G results in all four cities in 1H median download speeds in all four. In 2021 compared to just one in 2H 2020 short, EE performed well across the board. (Nottingham). Since then, O2 expanded its 5G service to Cardiff, Edinburgh, and Glasgow. Three showed expanded Everyday 5G Vodafone didn’t register any 5G availability in all four cities since 2H 2020. -

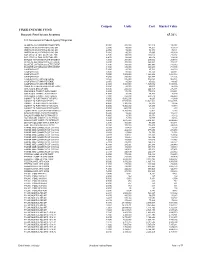

June 30, 2021

Coupon Units Cost Market Value FIXED INCOME FUND Domestic Fixed Income Securities 65.26% U.S. Government & Federal Agency Obligations ALAMEDA CA CORRIDOR TRANSPRTN 0.0000 200,000 192,815 196,952 AMERICAN MUNI PWR-OHIO INC OH 5.9390 80,000 88,201 117,679 AMERICAN MUNI PWR-OHIO INC OH 6.2700 50,000 50,373 70,481 AMERICAN MUNI PWR-OHIO INC OH 7.8340 80,000 87,695 132,393 BAY AREA CA TOLL AUTH TOLL BRI 6.2630 130,000 130,014 210,907 BAY AREA CA TOLL AUTH TOLL BRI 6.9070 80,000 80,010 139,634 BRAZOS TX HGR EDU AUTH STUDENT 1.9810 265,000 265,002 269,434 BUCKEYE OH TOBACCO SETTLEMENT 1.6500 370,000 369,997 378,327 BUCKEYE OH TOBACCO SETTLEMENT 1.7090 700,000 699,996 718,712 BUCKEYE OH TOBACCO SETTLEMENT 1.8090 695,000 694,995 714,500 CALIFORNIA ST 7.3000 80,000 85,722 128,033 CALIFORNIA ST 7.3500 80,000 80,729 128,811 CALIFORNIA ST 7.5500 1,070,000 1,464,882 1,824,349 CALIFORNIA ST 7.6250 250,000 263,977 421,136 CALIFORNIA ST UNIV REVENUE 3.0650 935,000 935,050 962,881 CALIFORNIA ST UNIV REVENUE 2.8970 85,000 85,002 84,927 CALIFORNIA ST UNIV REVENUE 2.9650 1,065,000 1,065,052 1,097,836 CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG NC HOSP 3.2040 80,000 80,000 85,303 CHICAGO IL BRD OF EDU 5.2820 225,000 224,307 236,371 CHICAGO IL TRANSIT AUTH SALES 6.2000 170,000 170,015 235,251 CHICAGO IL TRANSIT AUTH SALES 6.3000 30,000 30,261 30,703 CHICAGO IL TRANSIT AUTH SALES 5.3700 250,000 259,519 266,469 COMMIT TO PUR FNMA SF MT(OTC) 0.0000 -5,600,000 -9,625 -13,489 COMMIT TO PUR FNMA SF MTG 2.5000 32,525,000 33,542,683 33,640,506 COMMIT TO PUR FNMA SF MTG (OTC 0.0000 -7,300,000 -

Annual Report 2006 Dear Stockholder, 2006 Has Been an Exciting Year of Transformation

07-4863-1_VirginMedia10K_Cover.qxp 13/4/07 22:43 Page 1 (CyanMagentaYellowBlack plate) plate) plate)plate) Annual Report 2006 Dear Stockholder, 2006 has been an exciting year of transformation. Our hard working and dedicated employees have created a leading entertainment and communications business. We now have the U.K.’s first “quad-play” offering of television, broadband, and home and mobile phone services under the Virgin Media brand. Virgin is one of the most recognized consumer brands in the world, and has fantastic recognition in the U.K. In March 2006, our predecessor company NTL Incorporated merged with Telewest Global Inc. combining the two largest U.K. cable operators. Our cable network now passes approximately 51% of U.K. households and we serve almost 5 million customers. The merger has delivered significant synergies by reducing operating and capital costs from the combined businesses. We have made major process improvements in our customer operations and IT and have completed the first major billing system migration, driving two-thirds of our customers to one system. This is already paying dividends in terms of cost savings, improved flexibility and customer care. In July 2006, we added mobile telephone services to our product offering with the acquisition of Virgin Mobile, a leading U.K. mobile virtual network operator with approximately 4.5 million mobile phone customers. We have since merged ourretail channels across our Mobile and Cable segments and introduced significant cross-sell activity with the launch of offers such as our 4 for £40 at the end of September. Concurrent with the acquisition of Virgin Mobile we also secured a brand license agreement with the Virgin Group to use the ‘Virgin’ brand.