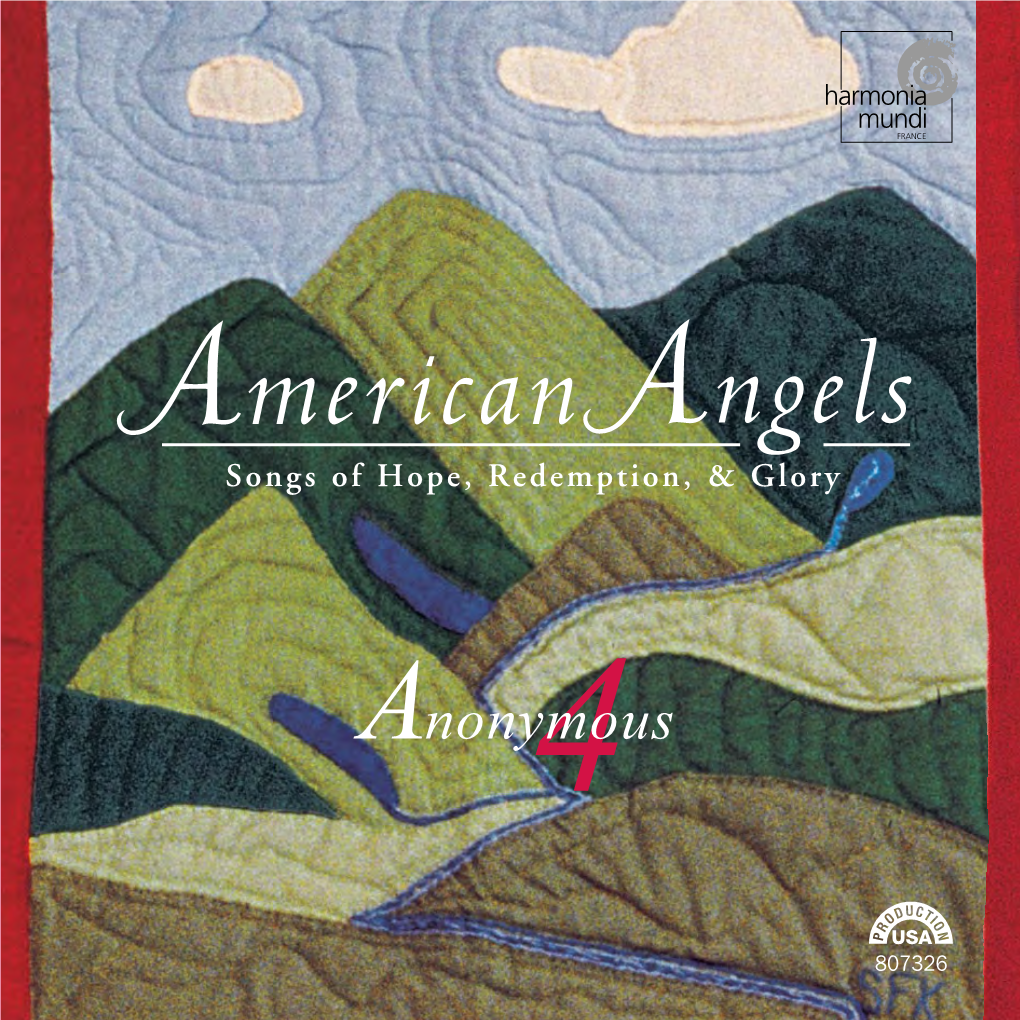

Angels American

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Christian Harmony, 2010 Edition 2016 Printing Page Location Title Text

Christian Harmony, 2010 Edition 2016 Printing Page Location Title Text Attribution Music Attribution 439 Lydia Village Hymns "C.L." in The Harmonist , 1837 407 Sweet Hope (Second) Christian Melodist A Selection of Psalm & Hymn Tunes , 1802 257 Jubilee Baltimore Collection , 1801 A Supplement to the Kentucky Harmony , 1820 508 Heavenly Rest Charles Wesley, 1744 A. Clark, 1867; Alto Wm. Walker 517 Rapture (Second) John Ogilvie, 1762 A. Reed, 1807 17 Call to Arms Courtney’s Christian Pocket Companion , 1805 A.A. Blocker, 1954 45b Lofty Sky Isaac Watts, 1719 A.D. Fillmore, 1865 37 Heaven’s My Home A.J. Showalter A.J. Showalter, 1889 189 One by One A.J. Showalter A.J. Showalter, 1889 54 My Trust Isaac Watts, 1709 A.M. Cagle, 1954 How Beautiful Heaven 77 Must Be Mrs. A. S. Bridgewater, 1920 A.P. Bland, 1920 Lady Touch Thy Harp 82t Again F.L. Stanton, 1881 A.R. Churchill, 1887 409t Little Marlborough Isaac Watts, 1707 Aaron Williams, 1763 519 Dalston Isaac Watts, 1719 Aaron Williams, 1763 398t St. Thomas Isaac Watts, 1719 Aaron Williams, c.1769 72t Jordan Samuel Stennett, 1787 Abner Jones, 1834 126 Ocean Isaac Watts, 1719 Adgate’s Philadelphia Harmony , 1789 72b Joyful News The American Baptist Sabbath-School Hymn-Book Aitken’s Compilation , 1787 432b Fish Pond Isaac Watts, 1707 Albert G. Holloway, Coosa County, Ala., 1873 390 Crown of Light Alexander Pope, 1712 Alexander Clark, 1853 480 Salineville Isaac Watts, 1707 Alexander Clark, 1853 287 Indian Convert T.D.C. in Youth's Magazine , 1814 Alexander Johnson, 1821; Alto, 1867 52 Newburg Isaac Watts, 1719 Amos Munson, 1798 58b Primrose Isaac Watts, 1707 Amzi Chapin, 1812 199 Vernon Charles Wesley, 1742 Amzi Chapin, 1813 455b Rockbridge Isaac Watts, 1709 Amzi Chapin, c.1798; Treble, 1847; Alto, 1867 419t Rockingham (First) Charles Wesley, 1739 Amzi Chapin; Arr. -

The Evolution of American Choral Music: Roots, Trends, and Composers Before the 20Th Century James Mccray

The Evolution of American Choral Music: Roots, Trends, and Composers before the 20th Century James McCray I hear America singing, the varied car- such as Chester, A Virgin Unspotted, ols I hear. David’s Lamentation, Kittery, I Am the —Walt Whitman Rose of Sharon, and The Lord Is Ris’n Leaves of Grass1 Indeed received numerous performanc- es in concerts by church, school, com- Prologue munity, and professional choirs. Billings Unlike political history, American cho- generally is acknowledged to be the most ral music did not immediately burst forth gifted of the “singing school” composers with signifi cant people and events. Choral of eighteenth-century America. His style, music certainly existed in America since somewhat typical of the period, employs the Colonial Period, but it was not until fuguing tunes, unorthodox voice lead- the twentieth century that its impact was ing, open-fi fth cadences, melodic writing signifi cant. The last half of the twentieth in each of the parts, and some surpris- century saw an explosion of interest in ing harmonies.11 By 1787 his music was choral music unprecedented in the his- widely known across America. tory of the country. American choral mu- Billings was an interesting personal- sic came of age on a truly national level, ity as well. Because out-of-tune singing and through the expansion of music edu- was a serious problem, he added a ’cello cation, technology, professional organiza- to double the lowest part.12 He had a tions, and available materials, the interest “church choir,” but that policy met re- in choral singing escalated dramatically. -

Hymnody of Eastern Pennsylvania German Mennonite Communities: Notenbüchlein (Manuscript Songbooks) from 1780 to 1835

HYMNODY OF EASTERN PENNSYLVANIA GERMAN MENNONITE COMMUNITIES: NOTENBÜCHLEIN (MANUSCRIPT SONGBOOKS) FROM 1780 TO 1835 by Suzanne E. Gross Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Maryland in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1994 Advisory Committee: Professor Howard Serwer, Chairman/Advisor Professor Carol Robertson Professor Richard Wexler Professor Laura Youens Professor Hasia Diner ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: HYMNODY OF EASTERN PENNSYLVANIA GERMAN MENNONITE COMMUNITIES: NOTENBÜCHLEIN (MANUSCRIPT SONGBOOKS) FROM 1780 TO 1835 Suzanne E. Gross, Doctor of Philosophy, 1994 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Howard Serwer, Professor of Music, Musicology Department, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland As part of an effort to maintain their German culture, the late eighteenth-century Mennonites of Eastern Pennsylvania instituted hymn-singing instruction in the elementary community schoolhouse curriculum. Beginning in 1780 (or perhaps earlier), much of the hymn-tune repertoire, previously an oral tradition, was recorded in musical notation in manuscript songbooks (Notenbüchlein) compiled by local schoolmasters in Mennonite communities north of Philadelphia. The practice of giving manuscript songbooks to diligent singing students continued until 1835 or later. These manuscript songbooks are the only extant clue to the hymn repertoire and performance practice of these Mennonite communities at the turn of the nineteenth century. By identifying the tunes that recur most frequently, one can determine the core repertoire of the Franconia Mennonites at this time, a repertoire that, on balance, is strongly pietistic in nature. Musically, the Notenbüchlein document the shift that occured when these Mennonite communities incorporated written transmission into their oral tradition. -

Reshaping American Music: the Quotation of Shape-Note Hymns by Twentieth-Century Composers

RESHAPING AMERICAN MUSIC: THE QUOTATION OF SHAPE-NOTE HYMNS BY TWENTIETH-CENTURY COMPOSERS by Joanna Ruth Smolko B.A. Music, Covenant College, 2000 M.M. Music Theory & Composition, University of Georgia, 2002 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Faculty of Arts and Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in Historical Musicology University of Pittsburgh 2009 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Joanna Ruth Smolko It was defended on March 27, 2009 and approved by James P. Cassaro, Adjunct Assistant Professor, Department of Music Mary S. Lewis, Professor, Department of Music Alan Shockley, Assistant Professor, Cole Conservatory of Music Philip E. Smith, Associate Professor, Department of English Dissertation Advisor: Deane L. Root, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Joanna Ruth Smolko 2009 iii RESHAPING AMERICAN MUSIC: THE QUOTATION OF SHAPE-NOTE HYMNS BY TWENTIETH-CENTURY COMPOSERS Joanna Ruth Smolko, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Throughout the twentieth century, American composers have quoted nineteenth-century shape- note hymns in their concert works, including instrumental and vocal works and film scores. When referenced in other works the hymns become lenses into the shifting web of American musical and national identity. This study reveals these complex interactions using cultural and musical analyses of six compositions from the 1930s to the present as case studies. The works presented are Virgil Thomson’s film score to The River (1937), Aaron Copland’s arrangement of “Zion’s Walls” (1952), Samuel Jones’s symphonic poem Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1974), Alice Parker’s opera Singers Glen (1978), William Duckworth’s choral work Southern Harmony and Musical Companion (1980-81), and the score compiled by T Bone Burnett for the film Cold Mountain (2003). -

MAY, 2011 Scarborough Presbyterian Church Scarborough, New York

THE DIAPASON MAY, 2011 Scarborough Presbyterian Church Scarborough, New York Cover feature on pages 30–32 May 2011 Cover A_518.indd 1 4/14/11 9:57:16 AM May 2011 pp. 2-19.indd 2 4/14/11 9:58:14 AM THE DIAPASON Letters to the Editor A Scranton Gillette Publication One Hundred Second Year: No. 3, Whole No. 1218 MAY, 2011 Review of Wayne Leupold Editions “major concerns” for any publisher. Established in 1909 ISSN 0012-2378 Bach Vol. 8 I’m not sure whether they should nec- An International Monthly Devoted to the Organ, I am well aware that one of the func- essarily be a major concern, but to me the Harpsichord, Carillon, and Church Music tions of a critical review is to criticize, the way a book feels and looks quite but that is certainly not the only func- obviously has an impact. If a book feels tion. As important as what one says nice, I want to pick it up, read and play negatively is what one says positively. It from it again and again. I think that’s CONTENTS Editor & Publisher JEROME BUTERA [email protected] is rare that one fi nds a work so poor that a highly desirable quality for any book 847/391-1045 good things cannot be said about it. But to have. FEATURES when one chooses to review a work with It is true that I wrote little about the Eighth International Organ and Associate Editor JOYCE ROBINSON so many outstanding features as the fi rst introductory essay, although I did com- Early Music Festival, Oaxaca, Mexico, [email protected] volume of Wayne Leupold Editions new ment on a few details in it. -

Kedron E Minor Amos Pilsbury, 1799 Scripture Hymns No

Charles Wesley, 1762 88. 88. (L. M.) Kedron E minor Amos Pilsbury, 1799 Scripture Hymns No. 686 Transcribed from The Kentucky Harmony, 1826. Arranged by Ananias Davisson, 1817 5 Tr. 1. Thou man of griefs, re mem ber me, Who ne ver canst thy self for get Thy last mys 2. When wrest ling in the strength of prayer Thy spi rit sunk be neath its load, Thy fee ble C. 3. A taste of thy tor men ting fears If now thou dost to me im part, Give the full 4. U nite my sor rows to thine own, And let me to my God com plain, Who mel ted T. 5. Fa ther, if I may call thee so, Re gard my fear ful heart's de sire, Re move this 6. I trem ble, lest the wrath d vine Which brui ses now my wret ched soul, Should bruise this B. 7. To thee my last dis tress I bring: The heigh tened fear of death I find; The ty rant 8. I de pre cate that death a lone, That end less ba nish ment from thee: O save, and 10 1. 2. 15 Tr. te rious a go ny, Thy fain ting pangs, and bloo dy sweat. flesh ab horred to bear The wrath of an Al migh ty God. C. vir tue of thy tears, The cries which pierced the Fa ther's heart. by thy Spi rit's groan, Can save me from that end less pain. T. load of guil ty woe, Nor let me in my sins ex pire. -

An Analysis of Shape Note Music in Terms of Information Entropy

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Honors Program Theses Spring 2021 Entropy in Music: An Analysis of Shape Note Music in Terms of Information Entropy Kyle Major [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.rollins.edu/honors Part of the Computer Sciences Commons, Musicology Commons, and the Music Practice Commons Recommended Citation Major, Kyle, "Entropy in Music: An Analysis of Shape Note Music in Terms of Information Entropy" (2021). Honors Program Theses. 152. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/honors/152 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Major 1 Entropy in Music: An Analysis of Shape Note Music in Terms of Information Entropy Honors Thesis, Rollins College Kyle Major Major 2 1. Abstract At first glance, the disciplines of music and computer science might seem like distinct and almost mutually exclusive fields. Music is often thought of as a subjective discipline rooted largely in a complex balance of aesthetic qualities such as pitch, rhythm, intonation, and dynamic contrast, while computer science is often seen as a discipline grounded in the ability to work with, and sometimes even think like calculating, logical, efficient machinery. And yet beneath the surface there are plenty of ways in which human sensibilities become important in computer science. One major example would be the entire subfield of Human Computer Interaction, which is built around the ability to help users take advantage of an interface to perform a task. -

Sacred Harp Singers, Professor Stephen A

―IF I CAN REACH THE CHARMING SOUND, I‘LL TUNE MY HARP AGAIN‖: THE FASOLA TUNEBOOK PUBLICATION RENAISSANCE By A. MITCHELL V. STECKER A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2019 © 2019 A. Mitchell V. Stecker ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are many individuals and groups whose support has facilitated the undertaking and completion of this document. First, I sincerely thank Dr. Laura Ellis and Dr. Jennifer Thomas for their time and energy spent not only on my thesis committee, but for all they both have invested in me over the better part of the past decade. I also wish to express my gratitude to the individuals and groups who gave of their time in answering questionnaires, giving interviews, and having informal conversations about this fascinating musical phenomenon, including the St. Louis Sacred Harp Singers, Professor Stephen A. Marini, and Micah Walter. I thank my parents for their unflagging support of my educational endeavors for the entirety of my life, and Sarah, whose love, encouragement, and strength are continual sources of inspiration. And finally, I would like to thank my singing friends everywhere, without the friendship and hospitality of whom I likely never would have discovered and been taken by this incredible music. How sweet the hours have passed away/Since we have met to sing and pray; How loath we are to leave the place/Where Jesus shows His smiling face. Oh could I stay with friends so kind,/How would it cheer my drooping mind! But duty makes me understand/That we must take the parting hand. -

Joseph Funk's "Allgemein Nützliche Choral-Music " (1816)

JOSEPH FUNK'S "ALLGEMEIN NÜTZLICHE CHORAL-MUSIC " (1816) By HARRY ESKEW As the main stream of the American singing-school movement during the early nineteenth century shifted gradually from the North to the South and West, an important area of musical activity was the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. In this Valley from 1816 to 1860 thirteen singing-school tune- books were published in at least thirty-two editions, beginning with Ananias Davisson's Kentucky Harmony. These Shenandoah Valley music publications are similar in several ways. The shape of each tunebook is oblong, being longer in width than height. Each collection opens with a theoretical introduction for teaching music reading in singing schools. The music of each tunebook is printed in shape notation, an aid to music reading which was widely accepted during this period in the South and West. These collections contain several types of vocal music set to religious texts, ranging from simple psalm and hymn tunes, including hymns of folk origin, to more elaborate fuging tunes and anthems. The music is given in open score, and the number of voice parts ranges from two to four, the latter being most frequent. The melody is normally found in the tenor part. These tunebooks were not limited to use in singing-school classes; they also found a place in religious services, as well as in other home and community activities. Although these Shenandoah Valley tunebooks are largely similar in format, contents, and usage, one of the earliest, entitled Allgemein nützliche Choral-Music, differs significantly from the others, for its language is Ger- man and its music is predominantly of German origin. -

Presbyterian Heritage Center Exhibit the Shape Note Tradition

attended only three sessions of school in late summer. Music fascinated him and his own curiosity would not be denied. Without a teacher, he mastered the music books Presbyterian Heritage Center Exhibit that were available to him. On the last day of December 1825, Ben White married Thurza Melvina The Shape Note Tradition Golightly. He met William Walker and dis- part of the Joyful, Joyful, We Adore Thee exhibit covered their mutual interest in music and they became friends. featuring 500 years of church music William Walker married Thurza’s sister, Amy, six years younger, in 1833. By this Shape Note Tradition time, Ben and William were working on a The repertoire of the nineteenth-century shape note music constitutes one of the collection of tunes that had been previously greatest American traditions. published. Walker took the shape note Shape notes may date from late 18th-century America. Shape note song books manuscript to New Haven, Connecticut, appeared at the beginning of the nineteenth century, when two publications came and The Southern Harmony (1835) became B.F. White and his wife, Thurza. out using shaped note heads – The Easy Instructor by William Little and William very popular in the South. Smith in 1801, and The Art of Singing (in three parts including the Musical Primer, In May 1842, Ben White moved his family to Georgia. He dreamt of compiling fourth edition) by Andrew Law in 1803, intended for use in singing schools. a tunebook. In one of his singing schools, he met Elisha J. Jing, who worked with Little and Smith used the four-shape system. -

Images and Comparisons of Melodious Accord Selections with Harmonia Sacra and Early Sources

APPENDIX B: IMAGES AND COMPARISONS OF MELODIOUS ACCORD SELECTIONS WITH HARMONIA SACRA AND EARLY SOURCES Included in this section are images from the earliest appearance in GCM,1 the current edition of HS-26, and other early sources of text and tune. Instances where the tune or text in MA differs from the early sources are also identified. Appendix B: MA #1 First line of text: “House of Our God, with Cheerful Anthems Ring;” author: Philip Doddridge (1702-51) Tune: Zion Meter: Meter (Metre 23 in HS-26): 10-10-10-10-11-11 First occurrence in GCM: 1st edition, 1832, page 57 2 1 For simplicity, in this section the abbreviations of MA, GCM, HS, and other sources will be set in Roman rather than Italic type. 2 The title pages of the respective editions of GCM and of other sources will be reproduced where they are first referenced in this appendix. 287 Page 57 Harmonia Sacra, 26th edition, 2008, title 288 HS-26, page 223 Source of text, as identified in GCM-1: Rippon Collection, 1807, Hymn 533 289 Hymn 533, continued Differences between GCM/HS, other sources, and MA: Key/Tune o Key: GCM/HS in C; MA in B-flat o Bar 11, beats 3-4 (circled): HS has quarter and two eighths; MA has two eighths and a quarter Text3 o 1.6 – GCM/Rippon “His blessings; HS/MA “His goodness”4 o 3.6 – GCM/Rippon “thy humble;” HS/MA “thine humble” o MA omits stanzas 2 and 5 of GCM; 2 of HS; 2, 5, and 6 of Rippon5 3 Stanza and line designations are the same as in Chapter 2 above: e.g., 1.6 refers to stanza 1, line 6. -

SACRED HARP SINGING SCHOOL & Potluck Supper Come Learn About and Participate in Community Singing

SACRED HARP SINGING SCHOOL & potluck supper Come learn about and participate in community singing Sacred harp, or shape-note singing descends from the singing-school movement of the 1700s and has been practiced continuously since then. The music is powerful and lively. Although the songs we sing are traditionally Christian, shape-note singing is not associated with any church or denomination. We don’t preach and we welcome all people of all faiths—or none. Please come to St Mary's Church Hamilton Village, 3916 Locust Walk on the UPenn campus, on Sunday September 13, 5:00-8:30 pm, for a good old-fashioned shape-note singing school and community supper. We’ll go over the basics of notes and rhythms and get practice leading songs. There will be plenty of singing, and we’ll teach the parts! Experience reading music is not required. All are welcome and songbooks will be available to borrow or purchase. The school is free. Please bring a potluck dish to share for the community supper if you are able. Please study the map. It's a little tricky to find - you have to go around the building to the cloister door. Please ring the bell in our “Philly Shape Note” sign. Contact: Rachel at [email protected] or 215-605-1621. PUBLIC TRANSPORT: The nearest subway stop is at 40th & Market, on the Market-Frankford Line. DRIVING DIRECTIONS: From I-76 East or West, take Exit 346A – South Street, which is a LEFT exit. Turn away from Center City and continue on Spruce Street.