Spectrophotometric Modeling and Mapping of Ceres

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surface Characteristics of Transneptunian Objects and Centaurs from Photometry and Spectroscopy

Barucci et al.: Surface Characteristics of TNOs and Centaurs 647 Surface Characteristics of Transneptunian Objects and Centaurs from Photometry and Spectroscopy M. A. Barucci and A. Doressoundiram Observatoire de Paris D. P. Cruikshank NASA Ames Research Center The external region of the solar system contains a vast population of small icy bodies, be- lieved to be remnants from the accretion of the planets. The transneptunian objects (TNOs) and Centaurs (located between Jupiter and Neptune) are probably made of the most primitive and thermally unprocessed materials of the known solar system. Although the study of these objects has rapidly evolved in the past few years, especially from dynamical and theoretical points of view, studies of the physical and chemical properties of the TNO population are still limited by the faintness of these objects. The basic properties of these objects, including infor- mation on their dimensions and rotation periods, are presented, with emphasis on their diver- sity and the possible characteristics of their surfaces. 1. INTRODUCTION cally with even the largest telescopes. The physical char- acteristics of Centaurs and TNOs are still in a rather early Transneptunian objects (TNOs), also known as Kuiper stage of investigation. Advances in instrumentation on tele- belt objects (KBOs) and Edgeworth-Kuiper belt objects scopes of 6- to 10-m aperture have enabled spectroscopic (EKBOs), are presumed to be remnants of the solar nebula studies of an increasing number of these objects, and signifi- that have survived over the age of the solar system. The cant progress is slowly being made. connection of the short-period comets (P < 200 yr) of low We describe here photometric and spectroscopic studies orbital inclination and the transneptunian population of pri- of TNOs and the emerging results. -

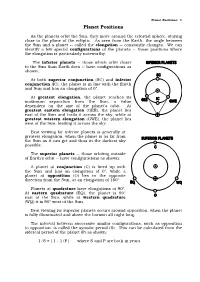

Planet Positions: 1 Planet Positions

Planet Positions: 1 Planet Positions As the planets orbit the Sun, they move around the celestial sphere, staying close to the plane of the ecliptic. As seen from the Earth, the angle between the Sun and a planet -- called the elongation -- constantly changes. We can identify a few special configurations of the planets -- those positions where the elongation is particularly noteworthy. The inferior planets -- those which orbit closer INFERIOR PLANETS to the Sun than Earth does -- have configurations as shown: SC At both superior conjunction (SC) and inferior conjunction (IC), the planet is in line with the Earth and Sun and has an elongation of 0°. At greatest elongation, the planet reaches its IC maximum separation from the Sun, a value GEE GWE dependent on the size of the planet's orbit. At greatest eastern elongation (GEE), the planet lies east of the Sun and trails it across the sky, while at greatest western elongation (GWE), the planet lies west of the Sun, leading it across the sky. Best viewing for inferior planets is generally at greatest elongation, when the planet is as far from SUPERIOR PLANETS the Sun as it can get and thus in the darkest sky possible. C The superior planets -- those orbiting outside of Earth's orbit -- have configurations as shown: A planet at conjunction (C) is lined up with the Sun and has an elongation of 0°, while a planet at opposition (O) lies in the opposite direction from the Sun, at an elongation of 180°. EQ WQ Planets at quadrature have elongations of 90°. -

The Opposition and Tilt Effects of Saturn's Rings from HST Observations

The opposition and tilt effects of Saturn’s rings from HST observations Heikki Salo, Richard G. French To cite this version: Heikki Salo, Richard G. French. The opposition and tilt effects of Saturn’s rings from HST observa- tions. Icarus, Elsevier, 2010, 210 (2), pp.785. 10.1016/j.icarus.2010.07.002. hal-00693815 HAL Id: hal-00693815 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00693815 Submitted on 3 May 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Accepted Manuscript The opposition and tilt effects of Saturn’s rings from HST observations Heikki Salo, Richard G. French PII: S0019-1035(10)00274-5 DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2010.07.002 Reference: YICAR 9498 To appear in: Icarus Received Date: 30 March 2009 Revised Date: 2 July 2010 Accepted Date: 2 July 2010 Please cite this article as: Salo, H., French, R.G., The opposition and tilt effects of Saturn’s rings from HST observations, Icarus (2010), doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2010.07.002 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. -

Summer ASTRONOMICAL CALENDAR

2020 Buhl Planetarium & Observatory ASTRONOMICAL CALENDAR Summer JUNE 2020 1 Mon M13 globular cluster well-placed for observation (Use telescope in Hercules) 3 Wed Mercury at highest point in evening sky (Look west-northwest at sunset) 5 Fri Full Moon (Strawberry Moon) 9 Tues Moon within 3 degrees of both Jupiter and Saturn (Look south before dawn) 13 Sat Moon within 3 degrees of Mars (Look southeast before dawn) Moon at last quarter phase 20 Sat Summer solstice 21 Sun New Moon 27 Sat Bootid meteor shower peak (Best displays soon after dusk) 28 Sun Moon at first quarter phase JULY 2020 5 Sun Full Moon (Buck Moon) Penumbral lunar eclipse (Look south midnight into Monday) Moon within 2 degrees of Jupiter (Look south midnight into Monday) 6 Mon Moon within 3 degrees of Saturn (Look southwest before dawn) 8 Wed Venus at greatest brightness (Look east at dawn) 11 Sat Moon within 2 degrees of Mars (Look south before dawn) 12 Sun Moon at last quarter phase 14 Tues Jupiter at opposition (Look south midnight into Wednesday) 17 Fri Moon just over 3 degrees from Venus (Look east before dawn) 20 Mon New Moon; Saturn at opposition (Look south midnight into Tuesday) 27 Mon Moon at first quarter phase 28 Tues Piscis Austrinid meteor shower peak (Best displays before dawn) 29 Wed Southern Delta Aquariid and Alpha Capricornid meteor showers peak AUGUST 2020 1 Sat Moon within 2 degrees of Jupiter (Look southeast after dusk) 2 Sun Moon within 3 degrees of Saturn (Look southeast after dusk) 3 Mon Full Moon (Sturgeon Moon) 9 Sun Conjunction of the Moon and -

POSTER SESSION I: CERES: MISSION RESULTS from DAWN 6:00 P.M

Lunar and Planetary Science XLVIII (2017) sess312.pdf Tuesday, March 21, 2017 [T312] POSTER SESSION I: CERES: MISSION RESULTS FROM DAWN 6: 00 p.m. Town Center Exhibit Area Russell C. T. Raymond C. A. De Sanctis M. C. Nathues A. Prettyman T. H. et al. POSTER LOCATION #171 Dawn at Ceres: What We Have Learned [#1269] A summary of the major discoveries and their implications at the close of the exploration of Ceres by Dawn. Ermakov A. I. Park R. S. Zuber M. T. Smith D. E. Fu R. R. et al. POSTER LOCATION #172 Regional Analysis of Ceres’ Gravity Anomalies [#1374] Put in geological and geomorphological context, the regional gravity anomalies give clues on the structure and evolution of Ceres’ crust. Nathues A. Platz T. Thangjam G. Hoffmann M. Mengel K. et al. POSTER LOCATION #173 Evolution of Occator Crater on (1) Ceres [#1385] We present recent results on the origin and evolution of the bright spots (Cerealia and Vinalia Faculae) at crater Occator on (1) Ceres. Buczkowski D. L. Scully J. E. C. Schenk P. M. Ruesch O. von der Gathen I. et al. POSTER LOCATION #174 Tectonic Analysis of Fracturing Associated with Occator Crater [#1488] The floor, walls, and ejecta of Occator Crater on Ceres are cut by multiple sets of linear and concentric fractures. We explore possible formation mechanisms. Pasckert J. H. Hiesinger H. Raymond C. A. Russell C. POSTER LOCATION #175 Degradation and Ejecta Mobility of Impact Craters on Ceres [#1377] We investigated the degradation and ejecta mobility of craters on Ceres, to investigate latitudinal variations, and to compare it with other planetary bodies. -

Historical Events Around US Neptune Cycles US Neptune: 22°25’ Virgo Greg Knell

Historical Events around US Neptune Cycles US Neptune: 22°25’ Virgo Greg Knell As we are in the midst of the United States’ Second Neptune Opposition, I initiated this research to consider the historical threads of this nation’s Neptunian narrative throughout its past 245 years. That this Neptune Opposition arrived to usher in the US’ First Pluto Return and its Fifth Chiron Return emphasized its prominence. Upon delving into this work, however, I came of the opinion that to isolate Neptune and its cycle would not do justice to what I sense is its place and purpose in the greater scheme of all relevant planetary cycles. Given that one Uranus cycle is roughly half of a Neptune cycle, Uranus Oppositions and Returns coincide with Neptune Squares, Oppositions, and Returns. Since its inception, the United States has had six Neptunian Timeline events: one return, two oppositions, and three squares. Among these, Pluto’s Timeline events have coincided four times. Given Pluto’s erratic orbit, this was by no means guaranteed. Pluto’s opposition occurred almost two-thirds through its entire orbit – in 1935, not even 100 years ago – instead of at the half way point of slightly before the turn of the Twentieth Century. This timing provides a clue as to the purpose, the plan, and the mission of these planetary cycles at this particular point in history. While it would be possible to isolate Neptune, perhaps, or any of the other cycles, I choose not to do so, as I do not believe that inquiry is worthy of individual pursuit for my purposes here. -

Lunar & Planetary Surface Power Management & Distribution

NASA SBIR 2020 Phase I Solicitation Z1.05 Lunar & Planetary Surface Power Management & Distribution Lead Center: GRC Participating Center(s): GSFC, JSC Technology Area: TA3 Space Power and Energy Storage Scope Title Innovative ways to transmit high power for lunar & Mars surface missions Scope Description The Global Exploration Roadmap (January 2018) and the Space Policy Directive (December 2017) detail NASA’s plans for future human-rated space missions. A major factor in this involves establishing bases on the lunar surface and eventually Mars. Surface power for bases is envisioned to be located remotely from the habitat modules and must be efficiently transferred over significant distances. The International Space Station (ISS) has the highest power (100kW), and largest space power distribution system with eight interleaved micro-grids providing power functions similar to a terrestrial power utility. Planetary bases will be similar to the ISS with expectations of multiple power sources, storage, science, and habitation modules, but at higher power levels and with longer distribution networks providing interconnection. In order to enable high power (>100kW) and longer distribution systems on the surface of the moon or Mars, NASA is in need of innovative technologies in the areas of lower mass/higher efficiency power electronic regulators, switchgear, cabling, connectors, wireless sensors, power beaming, power scavenging, and power management control. The technologies of interest would need to operate in extreme temperature environments, including lunar night, and could experience temperature changes from -153C to 123C for lunar applications, and -125C to 80C for Mars bases. In addition to temperature extremes, technologies would need to withstand (have minimal degradation from) lunar dust/regolith, Mars dust storms, and space radiation levels. -

March 21–25, 2016

FORTY-SEVENTH LUNAR AND PLANETARY SCIENCE CONFERENCE PROGRAM OF TECHNICAL SESSIONS MARCH 21–25, 2016 The Woodlands Waterway Marriott Hotel and Convention Center The Woodlands, Texas INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT Universities Space Research Association Lunar and Planetary Institute National Aeronautics and Space Administration CONFERENCE CO-CHAIRS Stephen Mackwell, Lunar and Planetary Institute Eileen Stansbery, NASA Johnson Space Center PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS David Draper, NASA Johnson Space Center Walter Kiefer, Lunar and Planetary Institute PROGRAM COMMITTEE P. Doug Archer, NASA Johnson Space Center Nicolas LeCorvec, Lunar and Planetary Institute Katherine Bermingham, University of Maryland Yo Matsubara, Smithsonian Institute Janice Bishop, SETI and NASA Ames Research Center Francis McCubbin, NASA Johnson Space Center Jeremy Boyce, University of California, Los Angeles Andrew Needham, Carnegie Institution of Washington Lisa Danielson, NASA Johnson Space Center Lan-Anh Nguyen, NASA Johnson Space Center Deepak Dhingra, University of Idaho Paul Niles, NASA Johnson Space Center Stephen Elardo, Carnegie Institution of Washington Dorothy Oehler, NASA Johnson Space Center Marc Fries, NASA Johnson Space Center D. Alex Patthoff, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Cyrena Goodrich, Lunar and Planetary Institute Elizabeth Rampe, Aerodyne Industries, Jacobs JETS at John Gruener, NASA Johnson Space Center NASA Johnson Space Center Justin Hagerty, U.S. Geological Survey Carol Raymond, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Lindsay Hays, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Paul Schenk, -

Contents JUPITER Transits

1 Contents JUPITER Transits..........................................................................................................5 JUPITER Conjunct Sun..............................................................................................6 JUPITER Opposite Sun............................................................................................10 JUPITER Sextile Sun...............................................................................................14 JUPITER Square Sun...............................................................................................17 JUPITER Trine Sun..................................................................................................20 JUPITER Conjunct Moon.........................................................................................23 JUPITER Opposite Moon.........................................................................................28 JUPITER Sextile Moon.............................................................................................32 JUPITER Square Moon............................................................................................36 JUPITER Trine Moon................................................................................................40 JUPITER Conjunct Mercury.....................................................................................45 JUPITER Opposite Mercury.....................................................................................48 JUPITER Sextile Mercury........................................................................................51 -

Neptune Closest to Earth for 2020 - a September 2020 Sky Event from the Astronomy Club of Asheville

Neptune Closest to Earth for 2020 - a September 2020 Sky Event from the Astronomy Club of Asheville Earth reaches “opposition” with the solar Not to Scale system’s most distant planet on September 11th. At opposition, speedier Earth, moving counterclockwise on its inside lane, laps the outer planet, positioning the Sun directly opposite the Earth from Neptune. This puts Neptune closest to Earth for the year and in great observing position for those using a telescope. Rising at dusk and setting at dawn, the planet Neptune is visible all night during the month of September. Located in the constellation Aquarius, Neptune is positioned some 2.7 billion miles (or 4 light-hours) away from Earth at “opposition” this month. _________________________________ At magnitude 7.8, Neptune will appear as a small blue disk in most amateur telescopes. You will find Neptune along the ecliptic in the constellation Aquarius this year. In September, it will be located about 2° southeast of the 4.2 magnitude star Phi (φ) Aquarii. Like Uranus, Neptune has an upper atmosphere with significant methane gas (CH4). Methane strongly absorbs red light; thus, the blue end of the light spectrum, from the reflected sunlight, is what primarily passes through to our eyes, when observing this distant planet. Neptune’s Discovery Neptune was the 2nd solar system planet to be discovered! Uranus’ discovery preceded it, when William Herschel observed its blue disk, quite by accident, in 1781. But Uranus’ orbit had an unexplained problem – a deviation that astronomers called a “perturbation”. Johannes Kepler’s laws of planetary motion and Isaac Newton’s laws of motion and gravity could not adequately explain this perturbation in Uranus’ orbit. -

Venus: Global Warming Gone Bad Earth & Venus: Sister Planets? Venus Earth

Venus: Global warming gone bad Earth & Venus: Sister planets? Venus Earth Mass 5x1024 kg 6x1024 kg a (semi- 0.7 AU 1 AU major axis) What is T at surface ~750 K ~300 K the boiling Temp of water? P at surface ~90 atm ~1 atm atm N2 and H2O CO2 and composition clouds H2SO4 clouds How do we know Venus’s surface temperature? How do we know Venus’s surface temperature? high energy low energy short wavelength long wavelength “bluer” “redder” hot cold How do we know Venus’s surface temperature? the Sun emits light Earth emits light here. T=6000 K here. T=300 K Venus emits light here. T=750 How do we know what the clouds are made of? Spectrum of planet with no atmosphere Amountof light observed above the atmosphere Wavelength of light (in the infrared) How do we know what the clouds are made of? Spectrum of Spectrum of planet with no planet with atmosphere atmosphere Wavelength at which a molecule in the atmosphere absorbs light Amountof light observed above the atmosphere Amountof light observed above the atmosphere Wavelength of light (in the Wavelength of light (in the infrared) infrared) How do we know what the clouds are made of? (Infrared light) How did Venus get so hot? Remember - all gases absorb light at specific wavelengths. “Greenhouse” gases (like carbon dioxide, water and methane) like to absorb in the infrared wavelengths. Planets emit light at infrared wavelengths (same as human bodies). Conclusio n? “Greenhouse” gases don’t lett the heat from the planet escape. -

Why Pluto Is Not a Planet Anymore Or How Astronomical Objects Get Named

3 Why Pluto Is Not a Planet Anymore or How Astronomical Objects Get Named Sethanne Howard USNO retired Abstract Everywhere I go people ask me why Pluto was kicked out of the Solar System. Poor Pluto, 76 years a planet and then summarily dismissed. The answer is not too complicated. It starts with the question how are astronomical objects named or classified; asks who is responsible for this; and ends with international treaties. Ultimately we learn that it makes sense to demote Pluto. Catalogs and Names WHO IS RESPONSIBLE for naming and classifying astronomical objects? The answer varies slightly with the object, and history plays an important part. Let us start with the stars. Most of the bright stars visible to the naked eye were named centuries ago. They generally have kept their old- fashioned names. Betelgeuse is just such an example. It is the eighth brightest star in the northern sky. The star’s name is thought to be derived ,”Yad al-Jauzā' meaning “the Hand of al-Jauzā يد الجوزاء from the Arabic i.e., Orion, with mistransliteration into Medieval Latin leading to the first character y being misread as a b. Betelgeuse is its historical name. The star is also known by its Bayer designation − ∝ Orionis. A Bayeri designation is a stellar designation in which a specific star is identified by a Greek letter followed by the genitive form of its parent constellation’s Latin name. The original list of Bayer designations contained 1,564 stars. The Bayer designation typically assigns the letter alpha to the brightest star in the constellation and moves through the Greek alphabet, with each letter representing the next fainter star.