The Opposition and Tilt Effects of Saturn's Rings from HST Observations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surface Characteristics of Transneptunian Objects and Centaurs from Photometry and Spectroscopy

Barucci et al.: Surface Characteristics of TNOs and Centaurs 647 Surface Characteristics of Transneptunian Objects and Centaurs from Photometry and Spectroscopy M. A. Barucci and A. Doressoundiram Observatoire de Paris D. P. Cruikshank NASA Ames Research Center The external region of the solar system contains a vast population of small icy bodies, be- lieved to be remnants from the accretion of the planets. The transneptunian objects (TNOs) and Centaurs (located between Jupiter and Neptune) are probably made of the most primitive and thermally unprocessed materials of the known solar system. Although the study of these objects has rapidly evolved in the past few years, especially from dynamical and theoretical points of view, studies of the physical and chemical properties of the TNO population are still limited by the faintness of these objects. The basic properties of these objects, including infor- mation on their dimensions and rotation periods, are presented, with emphasis on their diver- sity and the possible characteristics of their surfaces. 1. INTRODUCTION cally with even the largest telescopes. The physical char- acteristics of Centaurs and TNOs are still in a rather early Transneptunian objects (TNOs), also known as Kuiper stage of investigation. Advances in instrumentation on tele- belt objects (KBOs) and Edgeworth-Kuiper belt objects scopes of 6- to 10-m aperture have enabled spectroscopic (EKBOs), are presumed to be remnants of the solar nebula studies of an increasing number of these objects, and signifi- that have survived over the age of the solar system. The cant progress is slowly being made. connection of the short-period comets (P < 200 yr) of low We describe here photometric and spectroscopic studies orbital inclination and the transneptunian population of pri- of TNOs and the emerging results. -

Planet Positions: 1 Planet Positions

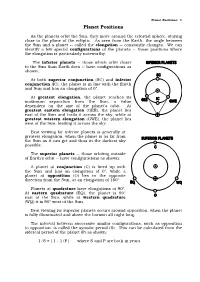

Planet Positions: 1 Planet Positions As the planets orbit the Sun, they move around the celestial sphere, staying close to the plane of the ecliptic. As seen from the Earth, the angle between the Sun and a planet -- called the elongation -- constantly changes. We can identify a few special configurations of the planets -- those positions where the elongation is particularly noteworthy. The inferior planets -- those which orbit closer INFERIOR PLANETS to the Sun than Earth does -- have configurations as shown: SC At both superior conjunction (SC) and inferior conjunction (IC), the planet is in line with the Earth and Sun and has an elongation of 0°. At greatest elongation, the planet reaches its IC maximum separation from the Sun, a value GEE GWE dependent on the size of the planet's orbit. At greatest eastern elongation (GEE), the planet lies east of the Sun and trails it across the sky, while at greatest western elongation (GWE), the planet lies west of the Sun, leading it across the sky. Best viewing for inferior planets is generally at greatest elongation, when the planet is as far from SUPERIOR PLANETS the Sun as it can get and thus in the darkest sky possible. C The superior planets -- those orbiting outside of Earth's orbit -- have configurations as shown: A planet at conjunction (C) is lined up with the Sun and has an elongation of 0°, while a planet at opposition (O) lies in the opposite direction from the Sun, at an elongation of 180°. EQ WQ Planets at quadrature have elongations of 90°. -

(101955) Bennu from OSIRIS-Rex Imaging and Thermal Analysis

ARTICLES https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-019-0731-1 Properties of rubble-pile asteroid (101955) Bennu from OSIRIS-REx imaging and thermal analysis D. N. DellaGiustina 1,26*, J. P. Emery 2,26*, D. R. Golish1, B. Rozitis3, C. A. Bennett1, K. N. Burke 1, R.-L. Ballouz 1, K. J. Becker 1, P. R. Christensen4, C. Y. Drouet d’Aubigny1, V. E. Hamilton 5, D. C. Reuter6, B. Rizk 1, A. A. Simon6, E. Asphaug1, J. L. Bandfield 7, O. S. Barnouin 8, M. A. Barucci 9, E. B. Bierhaus10, R. P. Binzel11, W. F. Bottke5, N. E. Bowles12, H. Campins13, B. C. Clark7, B. E. Clark14, H. C. Connolly Jr. 15, M. G. Daly 16, J. de Leon 17, M. Delbo’18, J. D. P. Deshapriya9, C. M. Elder19, S. Fornasier9, C. W. Hergenrother1, E. S. Howell1, E. R. Jawin20, H. H. Kaplan5, T. R. Kareta 1, L. Le Corre 21, J.-Y. Li21, J. Licandro17, L. F. Lim6, P. Michel 18, J. Molaro21, M. C. Nolan 1, M. Pajola 22, M. Popescu 17, J. L. Rizos Garcia 17, A. Ryan18, S. R. Schwartz 1, N. Shultz1, M. A. Siegler21, P. H. Smith1, E. Tatsumi23, C. A. Thomas24, K. J. Walsh 5, C. W. V. Wolner1, X.-D. Zou21, D. S. Lauretta 1 and The OSIRIS-REx Team25 Establishing the abundance and physical properties of regolith and boulders on asteroids is crucial for understanding the for- mation and degradation mechanisms at work on their surfaces. Using images and thermal data from NASA’s Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, and Security-Regolith Explorer (OSIRIS-REx) spacecraft, we show that asteroid (101955) Bennu’s surface is globally rough, dense with boulders, and low in albedo. -

(155140) 2005 UD and (3200) Phaethon*

The Planetary Science Journal, 1:15 (15pp), 2020 June https://doi.org/10.3847/PSJ/ab8e45 © 2020. The Author(s). Published by the American Astronomical Society. New Evidence for a Physical Link between Asteroids (155140) 2005 UD and (3200) Phaethon* Maxime Devogèle1 , Eric MacLennan2, Annika Gustafsson3 , Nicholas Moskovitz1 , Joey Chatelain4, Galin Borisov5,6, Shinsuke Abe7, Tomoko Arai8, Grigori Fedorets2,9, Marin Ferrais10,11,12, Mikael Granvik2,13 , Emmanuel Jehin10, Lauri Siltala2,14, Mikko Pöntinen2, Michael Mommert1 , David Polishook15, Brian Skiff1, Paolo Tanga16, and Fumi Yoshida8 1 Lowell Observatory, 1400 W. Mars Hill Rd., Flagstaff, AZ 86001, USA; [email protected] 2 Department of Physics, P.O. Box 64, FI-00014 University of Helsinki, Finland 3 Department of Astronomy & Planetary Science, Northern Arizona University, P.O. Box 6010, Flagstaff, AZ 86011, USA 4 Las Cumbres Observatory, CA, USA 5 Armagh Observatory and Planetarium, College Hill, Armagh BT61 9DG, UK 6 Institute of Astronomy and National Astronomical Observatory, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 72, Tsarigradsko Chaussèe Blvd., Sofia BG-1784, Bulgaria 7 Aerospace Engineering, Nihon University, 7-24-1 Narashinodai, Funabashi, Chiba 2748501, Japan 8 Planetary Exploration Research Center, Chiba Institute of Technology, Narashino, Japan 9 Astrophysics Research Centre, School of Mathematics and Physics, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast BT7 1NN, UK 10 Space sciences, Technologies & Astrophysics Research (STAR) Institute University of Liège Allée du 6 Août 19, B-4000 Liège, Belgium 11 Aix Marseille Université, CNRS, LAM (Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille) UMR 7326, F-13388, Marseille, France 12 Space sciences, Technologies, France 13 Division of Space Technology, LuleåUniversity of Technology, Box 848, SE-98128 Kiruna, Sweden 14 Nordic Optical Telescope, Apartado 474, E-38700 S/C de La Palma, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain 15 Faculty of Physics, Weizmann Institute of Science, 234 Herzl St. -

Summer ASTRONOMICAL CALENDAR

2020 Buhl Planetarium & Observatory ASTRONOMICAL CALENDAR Summer JUNE 2020 1 Mon M13 globular cluster well-placed for observation (Use telescope in Hercules) 3 Wed Mercury at highest point in evening sky (Look west-northwest at sunset) 5 Fri Full Moon (Strawberry Moon) 9 Tues Moon within 3 degrees of both Jupiter and Saturn (Look south before dawn) 13 Sat Moon within 3 degrees of Mars (Look southeast before dawn) Moon at last quarter phase 20 Sat Summer solstice 21 Sun New Moon 27 Sat Bootid meteor shower peak (Best displays soon after dusk) 28 Sun Moon at first quarter phase JULY 2020 5 Sun Full Moon (Buck Moon) Penumbral lunar eclipse (Look south midnight into Monday) Moon within 2 degrees of Jupiter (Look south midnight into Monday) 6 Mon Moon within 3 degrees of Saturn (Look southwest before dawn) 8 Wed Venus at greatest brightness (Look east at dawn) 11 Sat Moon within 2 degrees of Mars (Look south before dawn) 12 Sun Moon at last quarter phase 14 Tues Jupiter at opposition (Look south midnight into Wednesday) 17 Fri Moon just over 3 degrees from Venus (Look east before dawn) 20 Mon New Moon; Saturn at opposition (Look south midnight into Tuesday) 27 Mon Moon at first quarter phase 28 Tues Piscis Austrinid meteor shower peak (Best displays before dawn) 29 Wed Southern Delta Aquariid and Alpha Capricornid meteor showers peak AUGUST 2020 1 Sat Moon within 2 degrees of Jupiter (Look southeast after dusk) 2 Sun Moon within 3 degrees of Saturn (Look southeast after dusk) 3 Mon Full Moon (Sturgeon Moon) 9 Sun Conjunction of the Moon and -

Historical Events Around US Neptune Cycles US Neptune: 22°25’ Virgo Greg Knell

Historical Events around US Neptune Cycles US Neptune: 22°25’ Virgo Greg Knell As we are in the midst of the United States’ Second Neptune Opposition, I initiated this research to consider the historical threads of this nation’s Neptunian narrative throughout its past 245 years. That this Neptune Opposition arrived to usher in the US’ First Pluto Return and its Fifth Chiron Return emphasized its prominence. Upon delving into this work, however, I came of the opinion that to isolate Neptune and its cycle would not do justice to what I sense is its place and purpose in the greater scheme of all relevant planetary cycles. Given that one Uranus cycle is roughly half of a Neptune cycle, Uranus Oppositions and Returns coincide with Neptune Squares, Oppositions, and Returns. Since its inception, the United States has had six Neptunian Timeline events: one return, two oppositions, and three squares. Among these, Pluto’s Timeline events have coincided four times. Given Pluto’s erratic orbit, this was by no means guaranteed. Pluto’s opposition occurred almost two-thirds through its entire orbit – in 1935, not even 100 years ago – instead of at the half way point of slightly before the turn of the Twentieth Century. This timing provides a clue as to the purpose, the plan, and the mission of these planetary cycles at this particular point in history. While it would be possible to isolate Neptune, perhaps, or any of the other cycles, I choose not to do so, as I do not believe that inquiry is worthy of individual pursuit for my purposes here. -

Extended Mission Orbit #2 (XMO2, ~1500 Km Altitude)

Carol A. Raymond Deputy Principal Investigator SBAG 17 Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Caltech 13 Jun 2017 • Spacecraft and instruments are healthy and data return has been excellent to date • Primary mission ended on June 30 2016. All mission objectives and Level-1 requirements were met. • Extended mission at Ceres ends June 30 2017. All mission objectives and Level-1 requirements were met. • Primary mission data archive complete pending ongoing review; extended mission archive is up to date • NASA is considering options for continued operations beyond June 2017 2 • Loss of third reaction wheel on April 23rd limits Dawn’s lifetime – but otherwise does not affect the mission – dependent on hydrazine jets for attitude control – Lifetime decreases with orbit altitude • Dawn is currently in a ~20000x50000 km eccentric orbit • Recently performed opposition observation • Four special journal issues in work: – Icarus: Geological Mapping (in revision) – Icarus: Mineralogical Mapping (submitted) – MAPS: Composition/Crosscutting (in submission) – Icarus: Occator Crater (in progress) – Interest in a special issue on ground ice: contact Britney Schmidt if you would like to participate 3 Ceres Extended Mission Timeline Start of End of End of Extended Mission Extended Mission Project Operations Operations XM1 Science Plan Extended Mission Orbit #1 (XMO1, ~385 km altitude) • Obtain IR spectra of high-priority targets (VIR) ✓ • Expand high-resolution color imaging (FC) ✓ • Improve elemental mapping (GRaND) ✓ • Expand high-resolution surface coverage for topography -

Contents JUPITER Transits

1 Contents JUPITER Transits..........................................................................................................5 JUPITER Conjunct Sun..............................................................................................6 JUPITER Opposite Sun............................................................................................10 JUPITER Sextile Sun...............................................................................................14 JUPITER Square Sun...............................................................................................17 JUPITER Trine Sun..................................................................................................20 JUPITER Conjunct Moon.........................................................................................23 JUPITER Opposite Moon.........................................................................................28 JUPITER Sextile Moon.............................................................................................32 JUPITER Square Moon............................................................................................36 JUPITER Trine Moon................................................................................................40 JUPITER Conjunct Mercury.....................................................................................45 JUPITER Opposite Mercury.....................................................................................48 JUPITER Sextile Mercury........................................................................................51 -

Neptune Closest to Earth for 2020 - a September 2020 Sky Event from the Astronomy Club of Asheville

Neptune Closest to Earth for 2020 - a September 2020 Sky Event from the Astronomy Club of Asheville Earth reaches “opposition” with the solar Not to Scale system’s most distant planet on September 11th. At opposition, speedier Earth, moving counterclockwise on its inside lane, laps the outer planet, positioning the Sun directly opposite the Earth from Neptune. This puts Neptune closest to Earth for the year and in great observing position for those using a telescope. Rising at dusk and setting at dawn, the planet Neptune is visible all night during the month of September. Located in the constellation Aquarius, Neptune is positioned some 2.7 billion miles (or 4 light-hours) away from Earth at “opposition” this month. _________________________________ At magnitude 7.8, Neptune will appear as a small blue disk in most amateur telescopes. You will find Neptune along the ecliptic in the constellation Aquarius this year. In September, it will be located about 2° southeast of the 4.2 magnitude star Phi (φ) Aquarii. Like Uranus, Neptune has an upper atmosphere with significant methane gas (CH4). Methane strongly absorbs red light; thus, the blue end of the light spectrum, from the reflected sunlight, is what primarily passes through to our eyes, when observing this distant planet. Neptune’s Discovery Neptune was the 2nd solar system planet to be discovered! Uranus’ discovery preceded it, when William Herschel observed its blue disk, quite by accident, in 1781. But Uranus’ orbit had an unexplained problem – a deviation that astronomers called a “perturbation”. Johannes Kepler’s laws of planetary motion and Isaac Newton’s laws of motion and gravity could not adequately explain this perturbation in Uranus’ orbit. -

A Tale of Two Sides: Pluto's Opposition Surge in 2018 and 2019

EPSC Abstracts Vol. 14, EPSC2020-546, 2020, updated on 27 Sep 2021 https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-546 Europlanet Science Congress 2020 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. A Tale of Two Sides: Pluto's Opposition Surge in 2018 and 2019 Anne Verbiscer1, Paul Helfenstein2, Mark Showalter3, and Marc Buie4 1University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA ([email protected]) 2Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA ([email protected]) 3SETI Institute, Mountain View, CA, USA ([email protected]) 4Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, CO, USA ([email protected]) Near-opposition photometry employs remote sensing observations to reveal the microphysical properties of regolith-covered surfaces over a wide range of solar system bodies. When aligned directly opposite the Sun, objects exhibit an opposition effect, or surge, a dramatic, non-linear increase in reflectance seen with decreasing solar phase angle (the Sun-target-observer angle). This phenomenon is a consequence of both interparticle shadow hiding and a constructive interference phenomenon known as coherent backscatter [1-3]. While the size of the Earth’s orbit restricts observations of Pluto and its moons to solar phase angles no larger than α = 1.9°, the opposition surge, which occurs largely at α < 1°, can discriminate surface properties [4-6]. The smallest solar phase angles are attainable at node crossings when the Earth transits the solar disk as viewed from the object. In this configuration, a solar system body is at “true” opposition. When combined with observations acquired at larger phase angles, the resulting reflectance measurement can be related to the optical, structural, and thermal properties of the regolith and its inferred collisional history. -

Near-Infrared Mapping and Physical Properties of the Dwarf-Planet Ceres

A&A 478, 235–244 (2008) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20078166 & c ESO 2008 Astrophysics Near-infrared mapping and physical properties of the dwarf-planet Ceres B. Carry1,2,C.Dumas1,3,, M. Fulchignoni2, W. J. Merline4, J. Berthier5, D. Hestroffer5,T.Fusco6,andP.Tamblyn4 1 ESO, Alonso de Córdova 3107, Vitacura, Santiago de Chile, Chile e-mail: [email protected] 2 LESIA, Observatoire de Paris-Meudon, 5 place Jules Janssen, 92190 Meudon Cedex, France 3 NASA/JPL, MS 183-501, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91109-8099, USA 4 SwRI, 1050 Walnut St. # 300, Boulder, CO 80302, USA 5 IMCCE, Observatoire de Paris, CNRS, 77 Av. Denfert Rochereau, 75014 Paris, France 6 ONERA, BP 72, 923222 Châtillon Cedex, France Received 26 June 2007 / Accepted 6 November 2007 ABSTRACT Aims. We study the physical characteristics (shape, dimensions, spin axis direction, albedo maps, mineralogy) of the dwarf-planet Ceres based on high angular-resolution near-infrared observations. Methods. We analyze adaptive optics J/H/K imaging observations of Ceres performed at Keck II Observatory in September 2002 with an equivalent spatial resolution of ∼50 km. The spectral behavior of the main geological features present on Ceres is compared with laboratory samples. Results. Ceres’ shape can be described by an oblate spheroid (a = b = 479.7 ± 2.3km,c = 444.4 ± 2.1 km) with EQJ2000.0 spin α = ◦ ± ◦ δ =+ ◦ ± ◦ . +0.000 10 vector coordinates 0 288 5 and 0 66 5 . Ceres sidereal period is measured to be 9 074 10−0.000 14 h. We image surface features with diameters in the 50–180 km range and an albedo contrast of ∼6% with respect to the average Ceres albedo. -

Navigating Midlife

Navigating Midlife By Stephanie Johnson “For years Rita Golden Gelman felt she was living someone else’s life. She lived a privileged existence, attending glamorous parties and dining with celebrities. But none of it made her happy. Something was missing. When her marriage falters Rita decides to seize the opportunity to live her dream – take off and see the world on her own, and on her own terms. Fifteen years later, she is still traveling.” This publicity blurb on the back of a book entitled ‘Tales of a Female Nomad – Living At Large in the World” caught my eye. It spoke to something in me and I was hooked. The book is a fascinating read. While I would not want to live the life that Rita so enthusiastically embraces, there is something about her story that speaks to me, and I think possibly to many other women in the middle of their life. This incredible story of a women’s journey of discovery is more than simply a journal of physical discovery. It is one of emotional and spiritual discovery, of growth and of “relationship” – “relationship to self and others”. The honesty is raw and exciting, and something that is so easily lost in life, buried under responsibilities and society’s values. Rita’s book sparked in me a yearning to understand more about my own life, my own unspoken wishes and dreams and my own values. My own life is rich and rewarding and yet sometimes I feel an urge to break out. A lot of my women friends, also in the middle of their lives, have made radical changes in their lives.