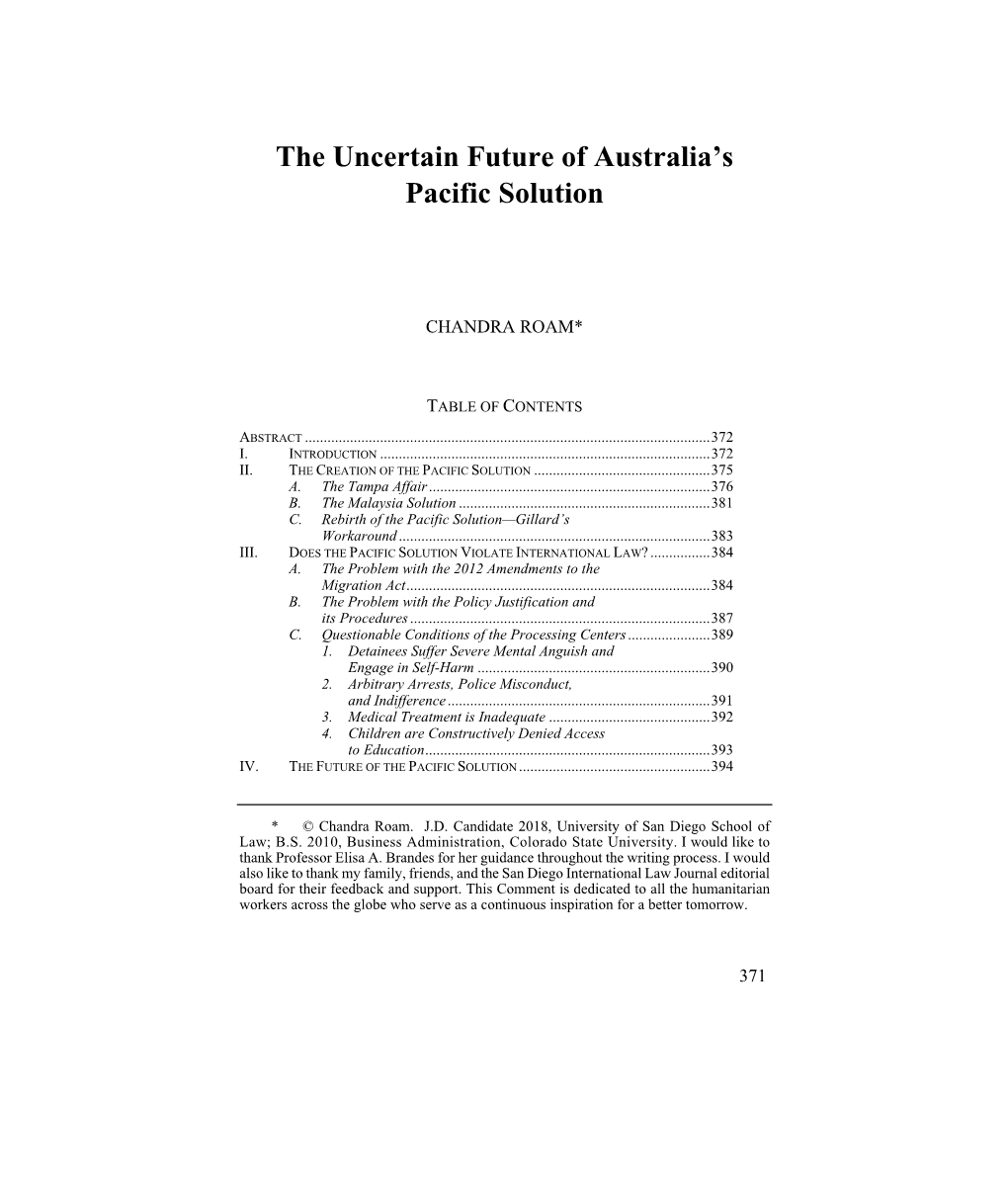

The Uncertain Future of Australia's Pacific Solution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Submission to the Senate Inquiry Into Manus Island and Nauru

Submission to the Inquiry into Serious allegations of abuse, self-harm and neglect of asylum seekers in relation to the Nauru Regional Processing Centre, and any like allegations in relation to the Manus Regional Processing Centre November 2016 Table of Contents Who we are ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Australian context ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Government policy ...................................................................................................................................... 4 The Australian Government and private contractors: Outsourcing our obligations .................................. 5 Legal and moral implications ....................................................................................................................... 7 Looking ahead.............................................................................................................................................. 8 Our Recommendations ................................................................................................................................ 9 References ................................................................................................................................................ -

William Yekrop (Australia) *

A/HRC/WGAD/2018/20 Advance edited version Distr.: General 20 June 2018 Original: English Human Rights Council Working Group on Arbitrary Detention Opinions adopted by the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention at its eighty-first session, 17–26 April 2018 Opinion No. 20/2018 concerning William Yekrop (Australia) * 1. The Working Group on Arbitrary Detention was established in resolution 1991/42 of the Commission on Human Rights, which extended and clarified the Working Group’s mandate in its resolution 1997/50. Pursuant to General Assembly resolution 60/251 and Human Rights Council decision 1/102, the Council assumed the mandate of the Commission. The Council most recently extended the mandate of the Working Group for a three-year period in its resolution 33/30. 2. In accordance with its methods of work (A/HRC/36/38), on 22 December 2017 the Working Group transmitted to the Government of Australia a communication concerning William Yekrop. The Government replied to the communication on 21 February 2018. The State is a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. 3. The Working Group regards deprivation of liberty as arbitrary in the following cases: (a) When it is clearly impossible to invoke any legal basis justifying the deprivation of liberty (as when a person is kept in detention after the completion of his or her sentence or despite an amnesty law applicable to him or her) (category I); (b) When the deprivation of liberty results from the exercise of the rights or freedoms guaranteed by articles 7, 13, 14, 18, -

3. Primary Decision-Making Procedures Under the Migration Act 1958 and Migration Regulations 1994

Chapter 3. Primary Decision-Making Procedures under the Migration Act 1958 and Migration Regulations 1994 This chapter will examine decision-making procedures for primary decisions and the role of policy in the Department and the Tribunals. This chapter also includes two appendices, outlining two significant new pieces of legislation – the Migration Amendment (Character and General Visa Cancellation) Act 2014 and the Migration and Maritime Powers Legislation Amendment (Resolving the Asylum Legacy Caseload) Act 2014. Part 1 – Decision-making at the primary level Visa application procedures The reasons why the Migration Act 1958 was amended with effect from 1 September 1994 to set out a detailed ‘code of procedure’ rather than relying on the common law principles of natural justice were examined in Chapter 2. The ‘code of procedure’ for making primary (Departmental) decisions1 can be found in Part 2, Division 3, Subdivision AB of the Act. Subdivision AB consists of ss 51–64 of the Act, which are entitled as follows: 51A. Exhaustive statement of natural justice hearing rule 52. Communication with Minister 54. Minister must have regard to all information in application 55. Further information may be given 56. Further information may be sought 57. Certain information must be given to applicant 58. Invitation to give further information or comments 59. Interviews 1 The Act usually refers to the ‘Minister’ as the decision maker. Subsection 496(1) provides that ‘[t]he Minister may, by writing signed by him or her, delegate to a person any of the Minister’s powers under this Act’. In practice, unless the Act specifically refers powers to the Minister personally, those powers are delegated to Departmental officers. -

Island of Despair

EMBARGOED COPY ISLAND OF DESPAIR AUSTRALIA’S “PROCESSING” OF REFUGEES ON NAURU Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2016 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, Cover photo: An Iranian refugee sits in an abandoned phosphate mine on Nauru international 4.0) licence. © Rémi Chauvin https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2016 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 12/4934/2016 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 1.1 Methodology 8 1.2 Terminology 9 2. BACKGROUND 11 2.1 Government of Australia’s policies towards people seeking protection 11 2.2 Nauru 12 2.3 Offshore “processing” of refugees 14 2.4 Legal standards 16 3. DRIVEN TO THE BRINK 19 3.1 Suicide and self-harm 19 3.2 Trapped in limbo 22 3.3 Inadequate medical care 24 3.4 Violations of children’s rights 29 4. -

Mr IB and Mr IC V Commonwealth of Australia (Department of Home Affairs)

Mr IB and Mr IC v Commonwealth of Australia (Department of Home Affairs) [2019] AusHRC 129 © Australian Human Rights Commission 2019. The Australian Human Rights Commission encourages the dissemination and exchange of information presented in this publication. All material presented in this publication is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence, with the exception of: • photographs and images; • the Commission’s logo, any branding or trademarks; • content or material provided by third parties; and • where otherwise indicated. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode. In essence, you are free to copy, communicate and adapt the publication, as long as you attribute the Australian Human Rights Commission and abide by the other licence terms. Please give attribution to: © Australian Human Rights Commission 2019. ISSN 1837-1183 Further information For further information about the Australian Human Rights Commission or copyright in this publication, please contact: Communications Unit Australian Human Rights Commission GPO Box 5218 SYDNEY NSW 2001 Telephone: (02) 9284 9600 Email: [email protected]. Design and layout Dancingirl Designs Printing Masterprint Pty Limited Mr IB and Mr IC v Commonwealth of Australia (Department of Home Affairs) [2019] AusHRC 129 Report into arbitrary detention Australian Human Rights Commission 2019 Contents 1 Introduction 7 2 Summary of findings and recommendations 7 3 Background 8 3.1 Mr IB 8 3.2 Mr IC 9 3.3 Current -

Immigration Detention in Nauru

Immigration Detention in Nauru March 2016 The Republic of Nauru, a tiny South Pacific island nation that has a total area of 21 square kilometres, is renowned for being one of the smallest countries in the world, having a devastated natural environment due to phosphate strip-mining, and operating a controversial offshore processing centre for Australia that has confined asylum seeking men, women, and children. Considered an Australian “client state” by observers, Nauru reported in 2015 that “the major source of revenue for the Government now comes from the operation of the Regional Processing Centre in Nauru.”1 Pointing to the numerous alleged abuses that have occurred to detainees on the island, a writer for the Guardian opined in October 2015 that the country had “become the symbol of the calculated cruelty, of the contradictions, and of the unsustainability of Australia’s $3bn offshore detention regime.”2 Nauru, which joined the United Nations in 1999, initially drew global attention for its migration policies when it finalised an extraterritorial cooperation deal with Australia to host an asylum seeker detention centre in 2001. This deal, which was inspired by U.S. efforts to interdict Haitian and Cuban asylum seekers in the Caribbean, was part of what later became known as Australia’s first “Pacific Solution” migrant deterrence policy, which involved intercepting and transferring asylum seekers arriving by sea—dubbed “irregular maritime arrivals” (IMAs)—to “offshore processing centres” in Nauru and Manus Island, Papua New Guinea.3 As part of this initial Pacific Solution, which lasted until 2008, the Nauru offshore processing centre was managed by the International Migration Organisation (IOM). -

Imagereal Capture

224 Australia’s Response to the Iraqi and Afghan Boat-People Volume 23(3) THE ‘TEMPORARY’ REFUGEES: AUSTRALIA’S LEGAL RESPONSE TO THE ARRIVAL OF IRAQI AND AFGHAN BOAT- PEOPLE HOSSEIN ESMAEILI* AND BELINDA WELLS** I. INTRODUCTION During the past year, over four thousand asylum seekers have travelled to Australia by boat, arriving without valid travel documents and seeking protection as refugees.* 1 The overwhelming majority of these new arrivals are from Iraq and Afghanistan.2 Typically, the final part of their travel to Australia has been facilitated by ‘people smugglers’ who operate from neighbouring South-East Asian countries, particularly Indonesia.3 The Australian Government has responded to these arrivals with a range of initiatives. Most controversially, it has created a two-tiered system of refugee protection: permanent protection visas are granted to those who apply for * LLB (Tehran) MA (TMU) LLM PhD (UNSW), Lecturer in Law, School of Law, University of New England. ** LLB (Adel) LLM (Lond), Lecturer in Law, School of Law, Flinders University of South Australia. The authors would like to thank the following people for their assistance during the research for this article: Robert Lachowicz, David Palmer, Tracy Ballantyne, Rohan Anderson, Stephen Wolfson, Marianne Dickie, John Eastwood, Des Hogan, Alistair Gee, Graham Thom, Shokoufeh Haghighat, Sam Berner and Michael Burnett. 1 “In 1999-00, 4 174 people arrived without authority on 75 Boats, compared with 920 on 42 Boats in 1998-9 (an increase of 354 per cent)”: Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs (“DIMA”), DIMA Fact Sheet 81: Unauthorised Arrivals by Air and Sea, 25 July 2000. -

Asylum Seekers in the Pacific (Manus, Nauru)

Dialogue: Asylum Seekers in the Pacific (Manus, Nauru) Guest edited by J C Salyer, Steffen Dalsgaard, and Paige West “It Is Not Because They Are Bad People”: Australia’s Refugee Resettlement in Papua New Guinea and Nauru j c salyer, steffen dalsgaard, and paige west Expanding Terra Nullius sarah keenan No Friend But the Mountains: A Reflection patrick kaiku Becoming through the Mundane: Asylum Seekers and the Making of Selves in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea paige west (continued on next page) The Contemporary Pacic, Volume 32, Number 2, 433–521 © 2020 by University of Hawai‘i Press 433 Dialogue: Asylum Seekers in the Pacific (Manus, Nauru) continued Guest edited by J C Salyer, Steffen Dalsgaard, and Paige West The Story of Holim Pas Tok Ples, a Short Film about Indigenous Language on Lou Island, Manus Province, Papua New Guinea kireni sparks-ngenge A Brief on the Intersection between Climate Change Impacts and Asylum and Refugee Seekers’ Incarceration on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea robert bino Weaponizing Ecocide: Nauru, Offshore Incarceration, and Environmental Crisis anja kanngieser From Drifters to Asylum Seekers steffen dalsgaard and ton otto The Denial of Human Dignity in the Age of Human Rights under Australia’s Operation Sovereign Borders j c salyer Weaponizing Ecocide: Nauru, Offshore Incarceration, and Environmental Crisis Anja Kanngieser The Pacific Solution (2001–2008) and Operation Sovereign Borders (2012–present) expanded Australia’s territorial and juridical borders through the establishment of three offshore regional processing centers in the Pacific nations of Nauru and Papua New Guinea (Manus Island) and on Christmas Island (an Australian territory in the Indian Ocean). -

Receiving Afghanistan's Asylum Seekers

FMR 13 19 Receiving Afghanistan’s asylum seekers: Australia, the Tampa ‘Crisis’ and refugee protection by William Maley n 22 January 2002, the announced that the government of the National Party, which made up the Chairman of the government- tiny Pacific nation of Nauru, a state country’s ruling coalition, and the O appointed Council for not party to the 1951 Convention, had opposition Australian Labor Party – Multicultural Australia, Neville Roach, agreed to the processing of asylum and it was left to minor parties, such resigned his position. In a newspaper claims on its soil. Nauru’s agreement as the Australian Democrats and the article three days later, this prominent was secured with a large aid package, Greens, to proffer a more nuanced and highly-respected businessman including payment of the unpaid account of the factors underpinning explained why he had taken such a Australian hospital bills of certain forced migration to Australia. dramatic step, which made headlines Nauruan citizens. Nonetheless, there are a number of right around the country. "If an advis- implications of these events which er", he wrote, "is faced with a Buoyed by the outcome of the Tampa government that has locked itself into Affair and trumpeting the merits of Logo of refugee infor- a position that is completely inflexi- its ‘Pacific solution’ to the problem of mation organisation ble, the opportunity to add value uninvited asylum seekers, the Howard reminding all non- disappears". The asylum seeker con- government was returned to office in indigenous troversy, he went on, "has a general election in November 2001. -

The Pacific Solution Or a Pacific Nightmare?: the Difference Between Burden Shifting and Responsibility Sharing

THE PACIFIC SOLUTION OR A PACIFIC NIGHTMARE?: THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN BURDEN SHIFTING AND RESPONSIBILITY SHARING Dr. Savitri Taylor* I. INTRODUCTION II. THE PACIFIC SOLUTION III. OFFSHORE PROCESSING CENTERS AND STATE RESPONSIBILITY IV. PACIFIC NIGHTMARES A. Nauru B. Papua New Guinea V. INTERPRETING NIGHTMARES VI. SPREADING NIGHTMARES VII. SHARING RESPONSIBILITY VIII. CONCLUSION I. INTRODUCTION The guarantee that persons unable to enjoy human rights in their country of nationality, who seek asylum in other countries, will not be returned to the country from which they fled is a significant achievement of international efforts to validate the assertion that those rights truly are the “rights of man.” There are currently 145 states,1 including Australia, that are parties to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (Refugees Convention)2 and/or the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees (Refugees Protocol).3 The prohibition on refoulement is the key provision of the Refugees Convention. Article 33(1) of the Refugees Convention provides that no state party “shall expel or return (refouler) a refugee in any manner * Senior Lecturer, School of Law, La Trobe University, Victoria 3086, Australia. 1 As of February 1, 2004. 2 July 28, 1951, 1954 Austl. T. S. No. 5 (entered into force for Australia and generally on April 22, 1954). 3 January 31, 1967, 1973 Austl. T. S. No. 37 (entered into force generally on October 4, 1967, and for Australia on December 13, 1973). 2 ASIAN-PACIFIC LAW & POLICY JOURNAL; Vol. 6, Issue 1 (Winter -

Asylum in Australia: 'Operation Sovereign Borders' And

Asylum in Australia: ‘Operation Sovereign Borders’ and International Law Joyce Chia,* Jane McAdam** and Kate Purcell*** I. Introduction On 18 September 2013, the day the Australian Coalition government was sworn into office, a new border protection policy took effect. Termed ‘Operation Sovereign Borders’ (OSB), it is based on the premise that Australia is facing a ‘border protection crisis’ that ‘requires the discipline and focus of a targeted military operation’.1 As a military-led operation, the government maintains a high degree of secrecy about its activities, which include intercepting and turning back asylum seeker boats. From early 2012 until mid-2013, there was a considerable increase in the number of asylum seekers seeking to reach Australia by boat — both in terms of total numbers (over 35,000 between January 2012 and July 2013) and intensity (over 3,000 arrivals per month between March and July 2013). Although these numbers remained very small in global terms (representing just three to four per cent of total asylum applications), 2 and 88 per cent of them were found to be refugees or otherwise in need of international protection,3 the unauthorised arrival of asylum seekers became one of the key political issues in the 2013 federal election. Playing upon generally poor community understandings about forced migration and common anxieties about ‘the uninvited’, terrorism, and security, politicians on both sides had championed increasingly draconian deterrence mechanisms — even when couched in the ostensibly humanitarian language of ‘saving lives at sea’.4 It was in this context that OSB was developed. This article begins by examining the background to OSB and what is known about its practical operation. -

Australian Border Policing: Regional 'Solutions' and Neocolonialism

RAC55310.1177/0306396813509197Race & ClassGrewcock 5091972014 Commentary SAGE Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, Washington DC Australian border policing: regional ‘solutions’ and neocolonialism MICHAEL GREWCOCK Abstract: Australia’s punitive border policing regime, aimed at deterring asylum seekers attempting unauthorised entry into the country, was ratcheted up even further in 2013 by the former Labor-led government and its successor (as of September 2013), the Liberal National Party Coalition. In effect, under the guise of combating ‘people-smuggling’, and a pledge to ‘Stop the Boats’, policies such as the mandatory detention of unauthorised arrivals and the use of off-shore detention facilities have been made even more draconian. Now the aim is to block entirely any right to resettlement or residence for refugees in Australia itself, using the weaker and poorer states of Nauru and Papua New Guinea, historically under Australia’s control, to act – to their own long-standing detriment – as detention and resettlement centres, for increasing numbers of migrants. Keywords: asylum-seeker, Australia border policing, immigration detention, Indonesia, LNPC, Nauru, Pacific solution, Papua New Guinea, people- smuggling, Stop the Boats On 19 July 2013, Australia’s Labor Prime Minister Kevin Rudd1 and Papua New Guinea’s Prime Minister, Peter O’Neill, convened a joint press conference to announce the signing of a Regional Settlement Arrangement (RSA) for asylum Michael Grewcock teaches law and criminology at the Faculty of Law, University of New South Wales, Sydney. His primary research interests are border policing and state crime. He is a member of the editorial board of the journal State Crime. Race & Class Copyright © 2014 Institute of Race Relations, Vol.