MEMORANDUM and ORDER Signed by Senior Judge William B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Print Layout 1

TECHNICAL PROGRAM Monday, March 19 5:00 – 8:00 pm Welcome Reception Tuesday, March 20 8:00 – 10:00 Session 1: Setting the Conference Context and Drivers Chair: Geoff Slaff (Amgen) Roger Perlmutter (Amgen) Conquering the Innovation Deficit in Drug Discovery Helen Winkle (CDER, FDA) Regulatory Modernization 10:00 – 10:30 Break Vendor and poster review 10:30 – 12:30 Session 2: Rapid Cell Line Development and Improved Expression System Development Chairs: Timothy Charlebois (Wyeth) and John Joly (Genentech) Amy Shen (Genentech) Stable Antibody Production Cell-Line Development with an Improved Selection Process and Accelerated Timeline Mark Leonard (Wyeth) High-Performing Cell-Line Development within a Rapid and Integrated Platform Process Control Pranhitha Reddy (Amgen) Applying Quality-by-Design to Cell Line Development Lin Zhang (Pfizer) Development of a Fully-Integrated Automated System for High-Throughput Screening and Selection of Single Cells Expressing Monoclonal Antibodies 12:30 – 2:00 Lunch Vendor and poster review 2:00 – 4:30 Session 3: High-Throughput Bulk Process Development Chairs: Brian Kelley (Wyeth) and Jorg Thommes (Biogen Idec) Colette Ranucci (Merck) Development of a Multi-Well Plate System for High-Throughput Process Development Min Zhang (SAFC Biosciences) CHO Media Library – an Efficient Platform for Rapid Development and Optimization of Cell Culture Media Supporting High Production of Pharmaceutical Proteins in Chinese Hamster Ovary Cells Nigel Titchener-Hooker The Use of Ultra-Scale-Down Approaches to Enable Rapid Investigation -

Moderna Vaccine Day Presentation

Zika Encoded VLP mRNA(s) RSV CMV + EBV SARS-CoV- RSV-ped 2 Flu hMPV/PIV3 H7N9 Encoded mRNA(s) Ribosome Protein chain(s) First Vaccines Day April 14, 2020 © 2020 M oderna Therapeutics Forward-looking statements and disclaimers This presentation contains forward-looking statements within the meaning of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995, as amended including, but not limited to, statements concerning; the impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on the Company’s clinical trials and operations; the timing and finalization of a dose-confirmation Phase 2 study and planning for a pivotal Phase 3 study for mRNA-1647; the status and outcome of the Phase 1 clinical trial for mRNA-1273 being conducted by NIH; the next steps and ultimate commercial plan for mRNA-1273; the size of the potential market opportunity for mRNA-1273; the size of the potential commercial market for novel vaccines produced by Moderna or others; the potential peak sales for the Company’s wholly-owned vaccines; the probability of success of the Company’s vaccines individually and as a portfolio; and the ability of the Company to accelerate the research and development timeline for any individual product or the platform as a whole. In some cases, forward-looking statements can be identified by terminology such as “will,” “may,” “should,” “expects,” “intends,” “plans,” “aims,” “anticipates,” “believes,” “estimates,” “predicts,” “potential,” “continue,” or the negative of these terms or other comparable terminology, although not all forward-looking statements contain these words. The forward-looking statements in this press release are neither promises nor guarantees, and you should not place undue reliance on these forward-looking statements because they involve known and unknown risks, uncertainties, and other factors, many of which are beyond Moderna’s control and which could cause actual results to differ materially from those expressed or implied by these forward-looking statements. -

Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc., a Subsidiary of Pfizer Inc Mylotarg

Mylotarg FDA ODAC Briefing Document 11 July 2017 WYETH PHARMACEUTICALS INC., A SUBSIDIARY OF PFIZER INC MYLOTARG (gemtuzumab ozogamicin; PF-05208747) In combination with chemotherapy for the treatment of previously untreated de novo CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia and as monotherapy for the treatment of CD33-positive acute myeloid leukemia in first relapse FDA ONCOLOGIC DRUGS ADVISORY COMMITTEE BRIEFING DOCUMENT (BLA 761060) Meeting Date: 11 July 2017 ADVISORY COMMITTEE BRIEFING MATERIALS: AVAILABLE FOR PUBLIC RELEASE 090177e18c1aa788\Approved\Approved On: 12-Jun-2017 13:05 (GMT) Page 1 Mylotarg FDA ODAC Briefing Document 11 July 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS...........................................................................................................2 LIST OF TABLES.....................................................................................................................5 LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................6 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................7 1.1. Introduction..............................................................................................................7 1.2. Rationale for Mylotarg Dosing Regimens ...............................................................8 1.3. Mylotarg in Patients With Previously Untreated De Novo AML............................9 1.4. Mylotarg in Patients With AML in First Relapse..................................................11 -

HEALTH BENEFITS Providing Value for Our Employees

HEALTH BENEFITS Providing Value for Our Employees March 2017 Business Roundtable CEO members lead companies with more than $6 trillion in annual revenues and nearly 15 million employees. The combined market capitalization of Business Roundtable member companies is the equivalent of nearly one-quarter of total U.S. stock market capitalization, and Business Roundtable members invest $103 billion annually in research and development — equal to 30 percent of U.S. private R&D spending. Our companies pay $226 billion in dividends to shareholders and generate $412 billion in revenues for small and medium-sized businesses annually. Business Roundtable companies also make more than $7 billion a year in charitable contributions. Please visit us at www.brt.org, check us out on Facebook and LinkedIn, and follow us on Twitter. Copyright © 2017 by Business Roundtable HEALTH BENEFITS Providing Value for Our Employees March 2017 March 2017 DEAR BUSINESS LEADERS AND STAKEHOLDERS: I am pleased to share with you a new report highlighting what leading U.S. companies are doing to improve health outcomes for our employees and their families. America’s employer-sponsored health benefits system is the foundation of health care in the United States. Of the 209 million Americans who are covered by health insurance plans, 85 percent — or 177 million Americans* — receive health coverage through an employer. This report demonstrates many different ways employers are helping to drive a health care system that delivers better health care quality and value. I hope you find this report helpful. Sincerely, Brian Moynihan Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Bank of America * Bureau of Labor Statistics, Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2015, Current Population Reports, September 2016. -

Amgen and Wyeth Statement on FDA Announcement About Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Blockers

Amgen and Wyeth Statement on FDA Announcement About Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Blockers August 4, 2009 THOUSAND OAKS, Calif. and COLLEGEVILLE, Pa., Aug. 4 /PRNewswire-FirstCall/ -- Amgen (Nasdaq: AMGN) and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, a division of Wyeth (NYSE: WYE), issued a statement in response to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announcement regarding the results of a safety review of Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) blockers [marketed as Remicade (infliximab), Enbrel (etanercept), Humira (adalimumab), Cimzia (certolizumab pegol) and Simponi (golimumab)]. This safety review was the subject of an FDA Early Communication in June 2008 pertaining to cases of malignancy in pediatric patients exposed to a TNF blocker. As a result of this review, the FDA has required strengthened warnings about the occurrence of lymphoma and other cancers in children and young adults using these medicines. AMGEN AND WYETH STATEMENT: Amgen and Wyeth believe that ENBREL continues to offer a favorable benefit-risk relationship for patients with the diseases for which it is indicated to treat, including moderate to severe Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA). JIA can be a serious and potentially debilitating condition. Amgen will work with the FDA to update the U.S. Prescribing Information, and Medication Guide for ENBREL as described in the FDA communication which can be read at http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm175803.htm. In addition, Amgen and Wyeth will communicate the revised product labeling to both physicians and patients. ENBREL was first approved for JIA in the U.S. in 1999. It is estimated through postmarketing data that approximately 13,847 pediatric patients have been treated with ENBREL globally through February 2009, accounting for approximately 44,600 patient-years of exposure. -

Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. 2012 Annual Report Valeant Inc

Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. 2012 Annual Report Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. 2012 Annual Report Valeant Gathering Momentum Company Overview Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. (NYSE/TSX:VRX) is a multinational specialty pharmaceutical company that develops and markets prescription and non-prescription pharmaceutical products that make a meaningful difference in patients’ lives. Valeant’s primary focus is principally in the areas of dermatology and neurology. The Company’s growth strategy is to acquire, develop and commercialize new products through strategic partnerships, and build on the company’s strength in dermatology and neurology. Valeant plans to strategically expand its pipeline by adding new compounds or products through product or company acquisitions and will maximize its pipeline through strategic partnering to optimize its research and development assets and strengthen ongoing internal development capabilities. Valeant’s strategic markets are primarily in the United States, Canada, Central and Eastern Europe, Latin America, Australia and South East Asia. Headquartered in Montreal, Quebec, Valeant has approximately 7,000 employees worldwide. FORWARD-LOOKING Statements In addition to current and historical information, this Annual Report contains forward-looking statements, including, without limitation, statements regarding our strategy, expected future revenue, the prospects for approval of product candidates and the timing of regulatory approvals, and the growth and future development of the company, its business units and its products. Words such as “expects,” “anticipates,” “intends,” “plans,” “should,” “could,” “would,” “may,” “will,” “believes,” “estimates,” “potential,” or “continue” or similar language identify forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties. Our actual results may differ materially from those contemplated by the forward-looking statements. -

Mvx List.Pdf

MVX_CODE manufacturer_name Notes status last updated date manufacturer_id AB Abbott Laboratories includes Ross Products Division, Solvay Inactive 16-Nov-17 1 ACA Acambis, Inc acquired by sanofi in sept 2008 Inactive 28-May-10 2 AD Adams Laboratories, Inc. Inactive 16-Nov-17 3 ALP Alpha Therapeutic Corporation Inactive 16-Nov-17 4 AR Armour part of CSL Inactive 28-May-10 5 AVB Aventis Behring L.L.C. part of CSL Inactive 28-May-10 6 AVI Aviron acquired by Medimmune Inactive 28-May-10 7 BA Baxter Healthcare Corporation-inactive Inactive 28-May-10 8 BAH Baxter Healthcare Corporation includes Hyland Immuno, Immuno International AG,and North American Vaccine, Inc./acquired somInactive 16-Nov-17 9 BAY Bayer Corporation Bayer Biologicals now owned by Talecris Inactive 28-May-10 10 BP Berna Products Inactive 28-May-10 11 BPC Berna Products Corporation includes Swiss Serum and Vaccine Institute Berne Inactive 16-Nov-17 12 BTP Biotest Pharmaceuticals Corporation New owner of NABI HB as of December 2007, Does NOT replace NABI Biopharmaceuticals in this codActive 28-May-10 13 MIP Emergent BioSolutions Formerly Emergent BioDefense Operations Lansing and Michigan Biologic Products Institute Active 16-Nov-17 14 CSL bioCSL bioCSL a part of Seqirus Inactive 26-Sep-16 15 CNJ Cangene Corporation Purchased by Emergent Biosolutions Inactive 29-Apr-14 16 CMP Celltech Medeva Pharmaceuticals Part of Novartis Inactive 28-May-10 17 CEN Centeon L.L.C. Inactive 28-May-10 18 CHI Chiron Corporation Part of Novartis Inactive 28-May-10 19 CON Connaught acquired by Merieux Inactive 28-May-10 21 DVC DynPort Vaccine Company, LLC Active 28-May-10 22 EVN Evans Medical Limited Part of Novartis Inactive 28-May-10 23 GEO GeoVax Labs, Inc. -

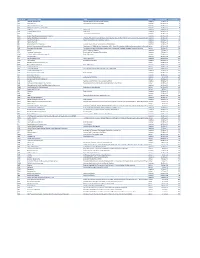

FDA Listing of Authorized Generics As of July 1, 2021

FDA Listing of Authorized Generics as of July 1, 2021 Note: This list of authorized generic drugs (AGs) was created from a manual review of FDA’s database of annual reports submitted to the FDA since January 1, 1999 by sponsors of new drug applications (NDAs). Because the annual reports seldom indicate the date an AG initially entered the market, the column headed “Date Authorized Generic Entered Market” reflects the period covered by the annual report in which the AG was first reported. Subsequent marketing dates by the same firm or other firms are not included in this listing. As noted, in many cases FDA does not have information on whether the AG is still marketed and, if not still marketed, the date marketing ceased. Although attempts have been made to ensure that this list is as accurate as possible, given the volume of d ata reviewed and the possibility of database limitations or errors, users of this list are cautioned to independently verify the information on the list. We welcome comments on and suggested changes (e.g., additions and deletions) to the list, but the list may include only information that is included in an annual report. Please send suggested changes to the list, along with any supporting documentation to: [email protected] A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V X Y Z NDA Applicant Date Authorized Generic Proprietary Name Dosage Form Strength Name Entered the Market 1 ACANYA Gel 1.2% / 2.5% Bausch Health 07/2018 Americas, Inc. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 ABCDEFG First Name Last Name

ABC D E F G Consultant, Speakers Bureau Stock or Other Financial 1 First Name Last Name Institution Grant/Research Support or Advisory Board Member Options University of Texas Southwestern Medical 2 Kenneth Altshuler MD Center Dallas Janssen Abbott, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Forest, Janssen, AstraZeneca, Bristol‐ AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Myers Squibb. Eli Lilly, 3 Lori Altshuler MD UCLA Abbott GlaxoSmithKline, Wyeth GlaxoSmithKline Western Psychiatric Institute Shire, Schering‐Plough, Jazz, 4 Boris Birmaher MD Pittsburg, PA Forest Solvay Abbott, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Elan, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson, Abbott, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly Research, Parke‐Davis, Janssen, Eli Lilly, Lilly Research, Abbott, AstraZeneca, Eli University of Texas Health Robert Wood Johnson and Sanofi‐Synthelabo, UCB Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, 5 Charles Bowden MD Science Center San Antonio Smith Kline Beecham Pharma, AstraZeneca, Pfizer Janssen AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Organon, Pfizer, Roche, 6 Robert Buchanan MD University of Maryland Janssen, Ortho‐McNeil Solvay, Wyeth Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol‐ Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol‐ Abbott, AZ, BMS, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer, Solvay, Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Janssen, Pfizer, Alamo, 7 Peter Buckley MD Medical College of Georgia Novartis Merck, Pfizer, Alamo, Novartis AstraZeneca Abbott, AstraZeneca, Merck, Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol‐ GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Eli Myers Squibb/Otsuka, Eli Lilly, Lilly, Pfizer, Ciba‐Geigy, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Robert Wood -

Amgen and Wyeth Statement on Outcome of Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee (DODAC) Meeting

Amgen and Wyeth Statement on Outcome of Dermatologic and Ophthalmic Drugs Advisory Committee (DODAC) Meeting June 18, 2008 FDA Advisory Committee Recommends Enbrel(R) (etanercept) for the Treatment of Children and Adolescents with Chronic Moderate to Severe Plaque Psoriasis THOUSAND OAKS, Calif. & COLLEGEVILLE, Pa.--(BUSINESS WIRE)--June 18, 2008--Amgen (NASDAQ: AMGN) and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, a division of Wyeth (NYSE: WYE), today issued the following statement on the outcome of today's meeting of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) Dermatologic and Ophthalmologic Drug Advisory Committee (DODAC) regarding the expanded use of ENBREL in treating pediatric patients with chronic moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. AMGEN AND WYETH STATEMENT: The Committee recommended, with an 8-5 vote, to approve ENBREL for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in children. The DODAC panel also provided input to the FDA regarding use in patients with more severe plaque psoriasis. Amgen and Wyeth are pleased the Committee adopted a position that is consistent with both companies' perspective that the benefits outweigh the risks in the population studied and that use should be reserved for appropriate patients. Amgen and Wyeth are hopeful that today represents an important step forward in working with the FDA to provide new treatment options for children living with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Despite the major impact this disease has on the lives of children and adolescents, there are currently no topical or systemic options approved in the U.S. for chronic use in this population. An expanded indication for ENBREL would address the unmet medical need for an approved and well-studied therapy in this small, under-served pediatric psoriasis patient population. -

Mckesson CORPORATION

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 SCHEDULE 14A Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (Amendment No. ) Filed by the Registrant ‘ Filed by a Party other than the Registrant Check the appropriate box: ‘ Preliminary Proxy Statement ‘ CONFIDENTIAL, FOR USE OF THE COMMISSION ONLY (AS PERMITTED BY RULE 14a-6(e)(2)) Definitive Proxy Statement ‘ Definitive Additional Materials ‘ Soliciting Material Pursuant to §240.14a-12 McKESSON CORPORATION (Name of Registrant as Specified In Its Charter) (Name of Person(s) Filing Proxy Statement, if other than the Registrant) Payment of Filing Fee (Check the appropriate box): No fee required. ‘ Fee computed on table below per Exchange Act Rules 14a-6(i)(4) and 0-11. (1) Title of each class of securities to which transaction applies: (2) Aggregate number of securities to which transaction applies: (3) Per unit price or other underlying value of transaction computed pursuant to Exchange Act Rule 0-11 (set forth the amount on which the filing fee is calculated and state how it was determined): (4) Proposed maximum aggregate value of transaction: (5) Total fee paid: ‘ Fee paid previously with preliminary materials. ‘ Check box if any part of the fee is offset as provided by Exchange Act Rule 0-11(a)(2) and identify the filing for which the offsetting fee was paid previously. Identify the previous filing by registration statement number, or the Form or Schedule and the date of its filing. (1) Amount Previously Paid: (2) Form, Schedule or Registration Statement No.: (3) Filing Party: (4) Date Filed: A LETTER FROM OUR INDEPENDENT CHAIR Dear Fellow Shareholders, First and foremost, on behalf of the Board of Directors, I would like to thank you for your investment in McKesson and for the confidence you place in this Board to oversee your interests in our Company particularly through the most unprecedented global health crisis in modern history. -

The Pfizer-Wyeth and Merck-Schering Plough Mergers

<:. t>-'- iRAOE COM!I.1/S ~\)'C-"0RECEIVED DOCUMENTS S~ . NOV 1 3111119 ) ' ./' Comments Submitted to the Federal Trade Commission o~/" the Pfizer-Wyeth and Merck-Schering Plough Mergers William S. Comanor and F. M. Scherer University ofCalifornia Harvard University Santa Barbara and Los Angeles Introduction We are both former Directors ofthe Bureau ofEconomics at the Federal Trade Commission, and have studied, lectured and written on the economics ofthe pharmaceutical industry for many years. As such, we feel obliged to submit these comments to the Commission because, in our judgment, both the Pfizer-Wyeth and Merck-Schering Plough mergers will further retard the rate ofpharmaceutical innovation and impose substantial consumer harm. This is an important matter, and we urge the Federal Trade Commission to consider these issues more fully. Pharmaceutical innovation is critically important for continued improvements in public health. l And for many decades, the major pharmaceutical companies have played an essential role in sustaining a rapid pace ofpharmaceutical innovation. Society has benefited greatly from their efforts. In recent years, however, the productivity ofthe innovation process has declined. The leading companies have spent increasing amounts on research and development without showing a corresponding increase in the number ofnew products introduced. Some companies have responded by seeking refuge in the greater scale achieved I H.E. Frech and Richard D. Miller, Health Care Matters: Pharmaceuticals, Obesity and the Quality ofLife, American Enterprise Institute, 2004. 1 through mergers. For the reasons outlined below, we believe that such efforts will merely depress further the rate ofinnovation. Many ofour views on these matters are contained in two earlier statements posted on the web site ofthe American Antitrust Institute, with whom we are both affiliated.