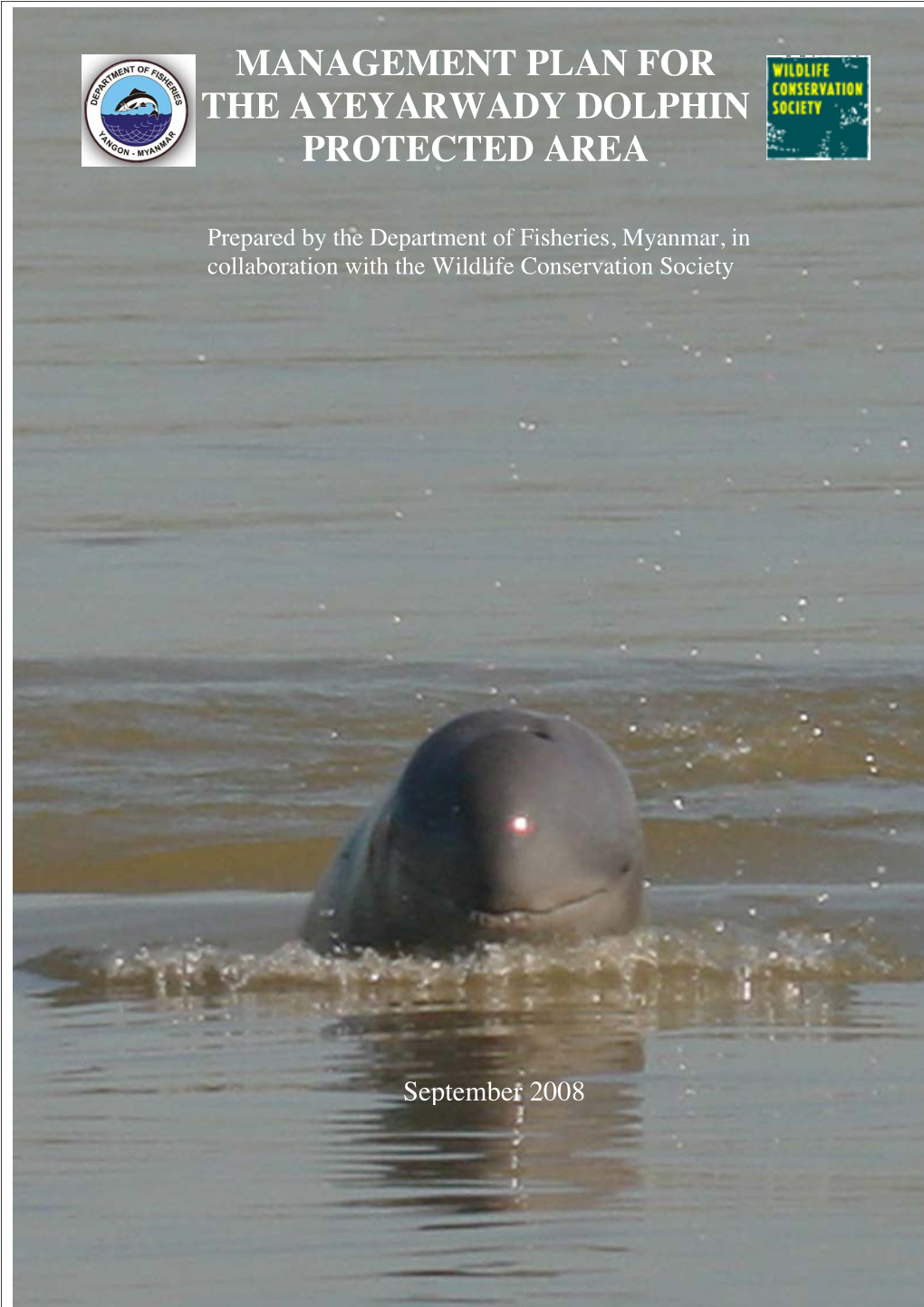

Ayeyarwady Dolphin Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STATUS and CONSERVATION of FRESHWATER POPULATIONS of IRRAWADDY DOLPHINS Edited by Brian D

WORKING PAPER NO. 31 MAY 2007 STATUS AND CONSERVATION OF FRESHWATER POPULATIONS OF IRRAWADDY DOLPHINS Edited by Brian D. Smith, Robert G. Shore and Alvin Lopez WORKING PAPER NO. 31 MAY 2007 sTATUS AND CONSERVATION OF FRESHWATER POPULATIONS OF IRRAWADDY DOLPHINS Edited by Brian D. Smith, Robert G. Shore and Alvin Lopez WCS Working Papers: ISSN 1530-4426 Copies of the WCS Working Papers are available at http://www.wcs.org/science Cover photographs by: Isabel Beasley (top, Mekong), Danielle Kreb (middle, Mahakam), Brian D. Smith (bottom, Ayeyarwady) Copyright: The contents of this paper are the sole property of the authors and cannot be reproduced without permission of the authors. The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) saves wildlife and wild lands around the world. We do this through science, conservation, education, and the man- agement of the world's largest system of urban wildlife parks, led by the flag- ship Bronx Zoo. Together, these activities inspire people to imagine wildlife and humans living together sustainably. WCS believes that this work is essential to the integrity of life on earth. Over the past century, WCS has grown and diversified to include four zoos, an aquarium, over 100 field conservation projects, local and international educa- tion programs, and a wildlife health program. To amplify this dispersed con- servation knowledge, the WCS Institute was established as an internal “think tank” to coordinate WCS expertise for specific conservation opportunities and to analyze conservation and academic trends that provide opportunities to fur- ther conservation effectiveness. The Institute disseminates WCS' conservation work via papers and workshops, adding value to WCS' discoveries and experi- ence by sharing them with partner organizations, policy-makers, and the pub- lic. -

Ichthyofaunal Diversity of Jinari River in Goalpara

CIBTech Journal of Zoology ISSN: 2319–3883 (Online) Online International Journal Available at http://www.cibtech.org/cjz.htm 2020 Vol.9, pp.30-35/Borah and Das Research Article [Open Access] ICHTHYOFAUNAL DIVERSITY OF JINARI RIVER IN GOALPARA, ASSAM, INDIA Dhiraj Kumar Borah and *Jugabrat Das Department of Zoology, Goalpara College, Goalpara, Assam, India, *Author for Correspondence: [email protected] ABSTRACT The present study attempts to access the ichthyofaunal diversity of Jinari river in Goalpara district of Assam, India. There was no previous report on piscine diversity of this river in Assam. Survey was conducted in the lower stretch of the river in Goalpara district from April 2018 to March 2019. Fish specimens were collected from five pre-selected sites, preserved and identified adopting standard methods. A total of 74 fish species belonging to nine (9) orders, 26 families and 58 genera were recorded. Cypriniformes was the dominant order with 35 species followed by Siluriformes with 19 species. IUCN status shows two vulnerable, eight near threatened and 66 species under the least concern category. Prevalence of anthropogenic threats like garbage dispersal and agricultural pesticide flow to the river, setting of brick industries on the bank, poison fishing in the upper stretch etc. may affect the fish population in this river. In this regard, awareness is the need of the hour among the inhabitants of the surrounding villages. Keywords: Ichthyofauna, Jinari River, Goalpara, Brahmaputra River, Assam INTRODUCTION The Northeastern region of India is considered to be one of the hotspots of freshwater fish biodiversity in the world (Ramanujam et al., 2010). -

2009 Board of Governors Report

American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists Board of Governors Meeting Hilton Portland & Executive Tower Portland, Oregon 23 July 2009 Maureen A. Donnelly Secretary Florida International University College of Arts & Sciences 11200 SW 8th St. - ECS 450 Miami, FL 33199 [email protected] 305.348.1235 23 June 2009 The ASIH Board of Governor's is scheduled to meet on Wednesday, 22 July 2008 from 1700- 1900 h in Pavillion East in the Hilton Portland and Executive Tower. President Lundberg plans to move blanket acceptance of all reports included in this book which covers society business from 2008 and 2009. The book includes the ballot information for the 2009 elections (Board of Govenors and Annual Business Meeting). Governors can ask to have items exempted from blanket approval. These exempted items will will be acted upon individually. We will also act individually on items exempted by the Executive Committee. Please remember to bring this booklet with you to the meeting. I will bring a few extra copies to Portland. Please contact me directly (email is best - [email protected]) with any questions you may have. Please notify me if you will not be able to attend the meeting so I can share your regrets with the Governors. I will leave for Portland (via Davis, CA)on 18 July 2008 so try to contact me before that date if possible. I will arrive in Portland late on the afternoon of 20 July 2008. The Annual Business Meeting will be held on Sunday 26 July 2009 from 1800-2000 h in Galleria North. -

Species Occurrence and Composition of Fish Fauna in Kyunmyityoe In, Ayeyarwady River Segment, Banmaw

1 Yadanabon University Research Journal, 2019, Vol-10, No.1 Species Occurrence and Composition of Fish Fauna In Kyunmyityoe In, Ayeyarwady River Segment, Banmaw Soe Soe Aye Abstract A study of the fish species occurrence and composition were undertaken during December 2017 to August 2018. A total of 57 species of fish belonging to 38 genera, 20 families and 8 orders were recorded from Kyunmyityoe In, Ayeyarwady river segment, Banmaw. Among the collected species order Cypriniformes was most dominant with 23 fish species (40%) followed by Siluriformes with 16 species (28%), Perciformes with 11 species (19%), Synbranchiformes with 3 species (5%), Clupeiformes, Osteoglossiformes, Beloniformes and Tetraodontiformes with one fish species (2% each). The largest number of species 46 species in each month of December and January and the smallest number of 20 species in April were recorded during the study period. Key words: fish species, occurrence,composition, Kyunmyityoe In, Ayeyarwady River Introduction Fishes form one of the most important groups of vertebrates, influencing its life in various ways. Fish diet provides protein, fats and vitamins A and D. A large amount of phosphorous and other elements are also present in it. They have a good taste and are easily digestible (Humbe et al., 2014). Fishes have formed an important item of human diet from time immemorial and are primarily caught for this purpose. Though the freshwater bodies contribute only 0.1% of the total water of the planet, it harbors 40% of fish species. Fish displays the greatest biodiversity of the vertebrates with over 27,500 species including 41 percent of freshwater species (Nelson, 1994 and 2006). -

Tfr 2019 8-1-13

www.sciencejournal.in UGC Approved Journal No: 63495 ICHTHYOFAUNAL DIVERSITY AND CONSERVATION STATUS ASSESSMENT OF DOYANG RESERVOIR, NAGALAND, INDIA Rongsen Kumzuk1, Deep Sankar Chini2, Manojit Bhattacharya2, Avijit kar2, Niladri Mondal2, B.C. Jha3, Bidhan Chandra Patra2 1Centre for Aquaculture Research, Extension and Livelihood, Department of Aquaculture Management and Technology, Vidyasagar University, Midnapore, West Bengal 721 102, India. 2 Department of Zoology, Vidyasagar University, Midnapore, West Bengal 721 102, India. 3 Central Inland Fisheries Research Institute, Barrackpore, Kolkata-700120 ABSTRACT The present study was incorporated with ichthyofaunal diversity and conservation assessment of freshwater fishes which are found in Doyang reservoir, Nagaland in between 2015 to 2018. Total 64 numbers of freshwater fishes in which 6 order and 16 families are found where most dominated order is Cypriniformes and family is Cyprinidae. The IUCN red list of threatened species find out that, 70% Least Concern (LC), 12% Near Threatened (NT), 8% Vulnerable (VU), 2% Endanger (EN), 3% Not Evaluated (NE) and 5% Data Deficient (DD) status have been availed by those species. As per IUCN, the population trends of the fish species also shows 75% are unknown, 11% stable and 14% have decreasing population trends in status. The distribution and abundance in different regions are also verified. The specified fishes are need immediate proper scientific management and conservation strategies for future availability of these freshwater fish species. KEYWORDS: Conservation, Distribution, Doyang Reservoir, Ichthyofaunal diversity, Nagaland. INTRODUCTION In India, the freshwater resources are found in different systems like ponds, canals, freshwater lakes, reservoirs, rivers, tanks, etc. About 10.86 million Indian people are directly or indirectly depended on fresh water fishery sectors (Sarkar, Sharma et al. -

The Nu River: a Habitat in Danger Krystal Chen, International Rivers

The Nu River: A Habitat in Danger Krystal Chen, International Rivers The Nu River is an important freshwater ecological system in Nu River (NFGRPA) was established in 2010, and approved by southwestern China. It boasts a wealth of fish species, more than 40 % the Ministry of Agriculture. The protected area covers 316 km of of which are endemic to the region. The region is worth protecting the Nu’s main stream and tributaries in the Nu Prefecture, where for its immense value to biodiversity research. However, the number seven species have been chosen as key protected species, including of fish species in the Nu has seen a sharp decrease in recent years, Schizothorax nukiangensis, Schizothorax gongshanensis, Tor hemispinus, and big fish are found and caught much less often. Overfishing and Placocheilus cryptonemus, Anguilla nebulosi, Akrokolioplax bicornis, and ecological degradation have been cited as possible causes. With five Pareuchiloglanis gongshanensis. Fifteen other species endemic to the Nu cascading hydropower stations planned in the upper and middle are also protected. reaches of the Nu, fish species in the Nu River now face alarming ZHENG Haitao conducted a preliminary analysis on the Index of threats. Biological Integrity (IBI) of the fish species in the upper and middle Fish biodiversity in the Nu River Region reaches of the Nu in 2004. The result showed that the integrity of fish species in the area is in good condition with low human intervention. According to CHEN Xiaoyong’s Fish Directory in Yunnan1 and Constraints mainly come from natural elements, such as habitat type other recent research2 conducted by his team, 62 species from 12 and food availability. -

Download Article (PDF)

e Z OL C o OCCASIONAL PAPER NO. 285 RECORDS OF THE ZOOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA Studies of Lower Vertebrates of Nagaland NIBEDITA SEN ROSAMMA MATHEW Zoological Survey of India, Eastern Regional Station, Risa Colony, Shillong - 793 003 Edited by the Director, Zoological Survey of India, Kolkata Zoological Survey of India Kolkata RECORDS OF THE ZOOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA OCCASIONAL PAPER NO. 285 2008 1-205 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 1 MAP OF NAGALAND SHOWING DISTRICTS ................................................................. 3 FIGURES 2-14 .......................................................................................................................... 4 PISCES ..................................................................................................................................... 11 SYSTEMATIC LIST .......................................................................................................... 11 SYSTEMATIC ACCOUNT ................................................................................................ 17 FIGURES 15-113 ............................................................................................................... 79 AMPlllBIA ............................................................................................................................. 107 SYSTEMATIC LIST ...................................................................................................... -

Ichthyofaunal Diversity of Arunachal Pradesh, India: a Part of Himalaya

International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies 2016; 4(2): 337-346 ISSN: 2347-5129 (ICV-Poland) Impact Value: 5.62 Ichthyofaunal diversity of Arunachal Pradesh, India: A (GIF) Impact Factor: 0.352 IJFAS 2016; 4(2): 337-346 part of Himalaya biodiversity hotspot © 2016 IJFAS www.fisheriesjournal.com Received: 28-01-2016 SD Gurumayum, L Kosygin, Lakpa Tamang Accepted: 01-03-2016 Abstract SD Gurumayum APRC, Zoological Survey of A systematic, updated checklist of freshwater fishes of Arunachal Pradesh is provided. A total of 259 fish India, Itanagar, Arunachal species under 105 genera, 34 families and 11 orders has been compiled based on present collection, Pradesh, India. available collections and literatures during the year 2014 to 2016. Thirty four fish species has been added to the previous report of 225 fish species. Besides, the state is type localities of 47 fish species and 32 L Kosygin species are considered endemic in the state. The fish fauna includes 19 threatened species as per IUCN Freshwater Fish Section, status. The state has high fisheries potential as it harbour many commercially important food, sport or Zoological Survey of India, ornamental fishes. The fish fauna is a mixture of endemic hill streams, Assamese, and widely distributed Indian Museum Complex forms. Kolkata, India. Keywords: Biodiversity, Fish, conservation status, commercial importance, Arunachal Pradesh Lakpa Tamang APRC, Zoological Survey of India, Itanagar, Arunachal Introduction Pradesh, India. Arunachal Pradesh is located between 26.28° N and 29.30° N latitude and 91.20° E and 97.30° E longitude and has 83,743 square km area. The state is a part of the Himalaya biodiversity hotspot with combination of diverse habitats with a high level of endemism. -

On a Recent Pioneering Taxonomic Study of the Fishes from Rivers Diyung, Vomvadung, Khualzangvadung, Tuikoi and Mahur in Dima Hasao District of Assam (India)

Transylv. Rev. Syst. Ecol. Res. 22.3 (2020), "The Wetlands Diversity" 83 ON A RECENT PIONEERING TAXONOMIC STUDY OF THE FISHES FROM RIVERS DIYUNG, VOMVADUNG, KHUALZANGVADUNG, TUIKOI AND MAHUR IN DIMA HASAO DISTRICT OF ASSAM (INDIA) Devashish KAR *, c.a and Dimos KHYNRIAM ** * Conservation Forum, Silchar, Assam, India, IN-788005; formerly Assam University, Department of Life Science, Silchar, Assam, India, IN-788011, [email protected], corresponding author ** Zoological Survey of India, North Eastern Regional Centre, Risa Colony, Fruit Garden, Shillong, India, IN-793003, [email protected] DOI: 10.2478/trser-2020-0019 KEYWORDS: ichthyofauna, conservation, Dima Hasao, Assam, India. ABSTRACT Ichthyofauna surveys in Diyung, Vomvadung, Khualzangvadung, Tuikoi, and Mahur rivers under Dima Hasao District of Assam resulted in the first report of 21 species of fish belonging to 19 genera, eight families, and four orders. These include Cypriniformes, Siluriformes, Synbranchiformes, and Perciformes. The species composition is highest in Vomvadung River with 11 species, followed by Diyung with eight species, Khualzangvadung with six species, Mohur with three species, and Tuikoi with two species. The conservation status of Systomus clavatus, Tor tor, Neolissochilus hexagonolepis, Neolissochilus hexastichus is near threatened, and Pterocryptis barakensis is endangered. RÉSUMÉ: Sur une etude taxonomique récente des poissons des rivières Diyung, Vomvadung, Khualzangvadung, Tuikoi et Mahur dans le district de Dima Hasao à Assam (Inde). L՚étude de l’ichtyofaune dans les rivières Diyung, Vomvadung, Khualzangvadung, Tuikoi et Mahur sous le district de Dima Hasao de l՚Assam a abouti au premier rapport de 21 espèces de poisons appartenant à 19 genres, huit familles et quatre ordres. Ceux-ci incluent les ypriniformes, les iluriformes, les Synbranchiformes et les Perciformes. -

Present Status and Habitat Ecology of Ompok Pabo (Ham-Buchanan) in Goronga Beel, Morigaon; Assam (India)

Available online a t www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com Pelagia Research Library Advances in Applied Science Research, 2012, 3 (1):481-488 ISSN: 0976-8610 CODEN (USA): AASRFC Present Status and Habitat Ecology of Ompok pabo (Ham-Buchanan) in Goronga Beel, Morigaon; Assam (India) Sarma. D1, Das. J 2, Goswami. U. C. 2 and Dutta A. 2 1Dept. of Zoology, Goalpara College, Goalpara(Assam) India 2Dept. of Zoology, Gauhati University, Guwahati(Assam) India _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT In the present communication, habitat ecology of Ompok pabo (Ham-Buchanan) in Goronga beel (Wetland), Morigaon; Assam were studied from September 2007 to August 2009. The wetland is riverine in origin and lies between the latitude of 19 0 2/ E and longitude of 26 015 / N. The endangered fish, Ompok pabo now restricted only few natural habitat including this wetland. Physico-chemical attributes of the wetland showed within permissible limit to support significantly in habitat suitability of the species. A total of 77 species recorded from the wetland during the period of investigation. The less recorded species in Bagridae family was also help in habitat suitability of Ompok pabo. The Shannon–Weiner diversity index of fish population of the wetland ranged from 2.11 to 3.41, which significantly indicates maximum species richness of the wetland. The floral and other faunal diversity of the wetland also showed important role in shaping microhabitat of the species. Key words: status, habitat ecology, Goronga beel , Assam. _____________________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The catfish Ompok pabo (Hamilton-Buchanan) locally known as pabda or pabo or butter fish is an indigenous freshwater small fish belonging to the family Siluridae of the order Siluriformes [1]. -

A Dataset of Fishes in and Around Inle Lake, an Ancient Lake of Myanmar, with DNA Barcoding, Photo Images and CT/3D Models

Biodiversity Data Journal 4: e10539 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.4.e10539 Data Paper A dataset of fishes in and around Inle Lake, an ancient lake of Myanmar, with DNA barcoding, photo images and CT/3D models Yuichi Kano‡, Prachya Musikasinthorn§, Akihisa Iwata |, Sein Tun¶¶, LKC Yun , Seint Seint Win#, Shoko Matsui¤,«, Ryoichi Tabata ¤, Takeshi Yamasaki», Katsutoshi Watanabe¤ ‡ Institute of Decision Science for Sustainable Society, Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan § Department of Fishery Biology, Faculty of Fisheries, Kasetsart University, Chatuchak, Bangkok, Thailand | Laboratory of Ecology and Environment, Division of Southeast Asian Area Studies, Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan ¶ Inle Lake Wildlife Sanctuary, Nature and Wildlife Conservation Division, Forest Department, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation, the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, Nyaung Shwe, Myanmar # Department of Zoology, Taunggyi University, Taunggyi, Myanmar ¤ Laboratory of Animal Ecology, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan « Osaka Museum of Natural History, Osaka, Japan » Yamashina Institute for Ornithology, Abiko, Japan Corresponding author: Katsutoshi Watanabe ([email protected]) Academic editor: Pavel Stoev Received: 17 Sep 2016 | Accepted: 03 Nov 2016 | Published: 09 Nov 2016 Citation: Kano Y, Musikasinthorn P, Iwata A, Tun S, Yun L, Win S, Matsui S, Tabata R, Yamasaki T, Watanabe K (2016) A dataset of fishes in and around Inle Lake, an ancient lake of Myanmar, with DNA barcoding, photo images and CT/3D models. Biodiversity Data Journal 4: e10539. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.4.e10539 Abstract Background Inle (Inlay) Lake, an ancient lake of Southeast Asia, is located at the eastern part of Myanmar, surrounded by the Shan Mountains. -

Diversity and Distribution of Cypriniformes in Kolodyne River Basin Of

DIVERSITY AND DISTRIBUTION OF CYPRINIFORMES IN KOLODYNE RIVER BASIN OF MIZORAM, INDIA By S. Beihrosa, Department of Environmental Science A Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Science of Mizoram University, Aizawl. Dedicated to my father S. Laitia (L), who passed away on 21st March, 2014. CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “Diversity and distribution of Cypriniformes in Kolodyne River basin of Mizoram, India” submitted to Mizoram University for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by S. Beihrosa, research scholar in the Department of Environmental Science, is a record of original work carried out during the period from 2013- 2016 is under our guidance and supervision. This work has not been submitted elsewhere for any degree. (Prof. LALNUNTLUANGA) (Dr. LALRAMLIANA) Supervisor Joint Supervisor Department of Environmental Science Department of Zoology Mizoram University Pachhunga University College MIZORAM UNIVERSITY AIZAWL-796004 27th October, 2016 DECLARATION I, Mr. S. Beihrosa, hereby declare that the subject matter of this thesis entitled “Diversity and distribution of Cypriniformes in Kolodyne River basin of Mizoram, India” is the record of work done by me, that the contents of this thesis did not form basis of the award of any previous degree to me or to the best of my knowledge to anybody else, and that the thesis has not been submitted by me for any research degree in any other University/Institute. This is being submitted to the Mizoram University for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Environmental Science.