Roehampton Community Capacity Report 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

253-255 Putney Bridge Road, London, SW15 2PU SELF-CONTAINED COMMERCIAL PREMISES to LET - A1 / A2 / B1 PLANNING CONSENT

253-255 Putney Bridge Road, London, SW15 2PU SELF-CONTAINED COMMERCIAL PREMISES TO LET - A1 / A2 / B1 PLANNING CONSENT FOR SALE / TO LET LOCATION: The available office and retail premises are prominently positioned fronting Putney Bridge Road, a popular residential and commercial area benefiting from the wide variety of local shops, restaurants, pubs along Putney Bridge Road. Putney High Street is similarly within walking distance from the available commercial premises and includes retailers such as; Waitrose, Costa Coffee, Byron, Bill's and The Boathouse along the river. Putney Bridge and Putney East underground stations (District Line) and Putney mainline station (direct to Waterloo via Clapham Junction & Vauxhall) are all within walking distance from the property. The area is similarly well connected with local bus routes. Cont’d MISREPRESENTATION ACT, 1967. Houston Lawrence for themselves and for the Lessors, Vendors or Assignors of this property whose agents they are, give notice that: These particulars do not form any part of any offer or contract: the statements contained therein are issued without responsibility on the part of the firm or their clients and therefore are not to be relied upon as statements or representations of fact: any intending tenant or purchaser must satisfy himself as to the correctness of each of the statements made herein: and the vendor, lessor or assignor does not make or give, and neither the firm or any of their employees have any authority to make or give, any representation or warranty whatever in relation to this property. VAT may be applicable to the terms quoted above. 253-255 Putney Bridge Road, London, SW15 2PU DESCRIPTION: The available commercial premises fronting Putney Bridge Road forms part of a mixed-use scheme comprising seven residential flats along with three commercial units. -

Peak Sub Region

Peak Sub Region Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment Final Report to Derbyshire Dales District Council, High Peak Borough Council and the Peak District National Park Authority June 2009 ekosgen Lawrence Buildings 2 Mount Street Manchester M2 5WQ TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................ 5 STUDY INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................. 5 OVERVIEW OF THE STUDY AREA ............................................................................................... 5 ROLE OF THE STUDY ................................................................................................................ 8 REPORT STRUCTURE.............................................................................................................. 10 2 SHLAA GUIDANCE AND STUDY METHODOLOGY..................................................... 12 SHLAA GUIDANCE................................................................................................................. 12 STUDY METHODOLOGY........................................................................................................... 13 3 POLICY CONTEXT.......................................................................................................... 18 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 18 NATIONAL, REGIONAL AND -

An Independent Study, the Future of Artists and Architecture? Screening Programme, Selected by Vanessa Scully 19 October 2019

Thamesmead Texas presents: An independent study, the future of artists and architecture? Screening programme, selected by Vanessa Scully 19 October 2019 Thamesmead Texas presents a selection of experimental and documentary films on social housing, gentrification and regeneration from the 1970’s – present day London. Selected by artist Vanessa Scully, as part of the series ‘Thamesmead Texas presents: An independent study, the future of artists and architecture? This screening event sits within a new installation entitled ‘Heavy View’ by British Artist Laura Yuile that developed out of Yuile’s consideration of technological and architectural obsolescence. TACO!, 30 Poplar Place, Thamesmead, London SE28 8BA. Saturday 19 October, 7-10pm. Part One: Meanwhile space in London*, shorts Katharine Meynell, Kissing (2014), 3:00 mins, digital video John Smith, Dungeness (1987) 3:35 mins, 16mm film William Raban, Cripps at Acme (1981), 5:35 mins, 16mm film Wendy Short, Overtime (2016), 10:09 mins, digital video Channel 4, Home Truths – Art and Soul (2014), 4:51 mins, digital video Vanessa Scully, No 1 The Starliner v1 (2014), 1:05 mins, 35mm slides and digital video Vanessa Scully, No 1 The Starliner v2 (2014), 1:05 mins, 35mm slides and digital video Vanessa Scully, No 1 The Starliner v3 (2014), 1:05 mins, 35mm slides and digital video John Smith & Jocelyn Pook, Blight (1996), 16 mins, 16mm film Part Two: A history of social housing in London, feature Tom Cordell, Utopia London (2010), 82 mins, digital video and archive material Tessa Garland, Here East (2017), 5:42 mins, HD video Part One: into his thirties) a figure to add to the pantheon of profoundly subversive, wildly misbehaved, and Katharine Meynell, Kissing (2014) perhaps genuinely unhinged twentieth-century artists, alongside Jack Smith, Harry Smith, Kenneth “Made in response to a word drawn from a hat with Anger, Chris Burden, Joe Coleman, and others.” LUX 13 Critical Forum, I kissed the iconic Balfron Jared Rap-fogelVol. -

Historical and Contemporary Archaeologies of Social Housing: Changing Experiences of the Modern and New, 1870 to Present

Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Emma Dwyer School of Archaeology and Ancient History University of Leicester 2014 Thesis abstract: Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Emma Dwyer This thesis has used building recording techniques, documentary research and oral history testimonies to explore how concepts of the modern and new between the 1870s and 1930s shaped the urban built environment, through the study of a particular kind of infrastructure that was developed to meet the needs of expanding cities at this time – social (or municipal) housing – and how social housing was perceived and experienced as a new kind of built environment, by planners, architects, local government and residents. This thesis also addressed how the concepts and priorities of the Victorian and Edwardian periods, and the decisions made by those in authority regarding the form of social housing, continue to shape the urban built environment and impact on the lived experience of social housing today. In order to address this, two research questions were devised: How can changing attitudes and responses to the nature of modern life between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries be seen in the built environment, specifically in the form and use of social housing? Can contradictions between these earlier notions of the modern and new, and our own be seen in the responses of official authority and residents to the built environment? The research questions were applied to three case study areas, three housing estates constructed between 1910 and 1932 in Birmingham, London and Liverpool. -

Future Forms and Design for Sustainable Cities This Page Intentionally Left Blank H6309-Prelims.Qxd 6/24/05 9:20 AM Page Iii

H6309-Prelims.qxd 6/24/05 9:20 AM Page i Future Forms and Design for Sustainable Cities This page intentionally left blank H6309-Prelims.qxd 6/24/05 9:20 AM Page iii Future Forms and Design for Sustainable Cities Mike Jenks and Nicola Dempsey AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON • NEW YORK • OXFORD PARIS • SAN DIEGO • SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Architectural Press is an imprint of Elsevier H6309-Prelims.qxd 6/24/05 9:20 AM Page iv Architectural Press An imprint of Elsevier Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP 30 Corporate Drive, Burlington, MA 01803 First published 2005 Editorial matter and selection Copyright © 2005, Mike Jenks and Nicola Dempsey. All rights reserved Individual contributions Copyright © 2005, the Contributors. All rights reserved No parts of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London, England W1T 4LP. Applications for the copyright holder’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science and Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: (ϩ44) (0) 1865 843830; fax: (ϩ44) (0) 1865 853333; e-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier homepage (http://www.elsevier.com), by selecting ‘Customer Support’ and then ‘Obtaining Permissions’. -

Introduction

Official WANDSWORTH BOROUGH COUNCIL BUILDINGS OF SPECIAL ARCHITECTURAL OR HISTORIC INTEREST INTRODUCTION The Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport is required to compile lists of buildings of special architectural or historic interest for the guidance of local planning authorities. Conservation policies are often based on the lists, which are being revised within nationally applied surveys of specific building types. How Buildings are Chosen The principles of selection for these lists were originally drawn up by an expert committee of architects, antiquarians and historians, and are still followed, although now adapted to thematic surveys and Post-War buildings. Buildings that qualify for listing are:- (a) All buildings before 1700 which survive in anything like their original condition. (b) Most buildings between 1700-1840, though some selection is necessary. (c) Between 1840 and 1914 only buildings of definite quality and character, the selection being designed to include the best examples of particular building types. (d) Selected buildings from the period after 1914 are selected on the same basis. (e) Buildings under 30 years old (but more than ten) are normally listed only if they are of outstanding quality and under threat. In choosing buildings, particular attention is paid to:- � Special value within certain types, either for architectural or planning reasons or as illustrating social and economic history (for instance, industrial buildings, railway stations, schools, hospitals, prisons, theatres). � Technological innovation or virtuosity (for instance cast iron, prefabrication, or the early use of concrete). � Group value, especially as examples of town planning (for instance, squares, terraces or model estates). � Association with well-known characters or events. -

2017 Annual Report Plc Redrow Sense of Wellbeing

Redrow plc Redrow Redrow plc Redrow House, St. David’s Park, Flintshire CH5 3RX 2017 Tel: 01244 520044 Fax: 01244 520720 ANNUAL REPORT Email: [email protected] Annual Report 2017 Annual Report 01 STRATEGIC REPORT STRATEGIC REDROW ANNUAL REPORT 2017 A Better Highlights Way to Live £1,660m £315m 70.2p £1,382m £250m 55.4p £1,150m £204m 44.5p GOVERNANCE REPORT GOVERNANCE 15 16 17 15 16 17 15 16 17 £1,660m £315m 70.2p Revenue Profit before tax Earnings per share +20% +26% +27% 17p 5,416 £1,099m 4,716 £967m STATEMENTS FINANCIAL 4,022 10p £635m 6p 15 16 17 15 16 17 15 16 17 Contents 17p 5,416 £1,099m Dividend per share Legal completions (inc. JV) Order book (inc. JV) SHAREHOLDER INFORMATION SHAREHOLDER STRATEGIC REPORT GOVERNANCE REPORT FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SHAREHOLDER 01 Highlights 61 Corporate Governance 108 Independent Auditors’ INFORMATION +70% +15% +14% 02 Our Investment Case Report Report 148 Corporate and 04 Our Strategy 62 Board of Directors 114 Consolidated Income Shareholder Statement Information 06 Our Business Model 68 Audit Committee Report 114 Statement of 149 Five Year Summary 08 A Better Way… 72 Nomination Committee Report Comprehensive Income 16 Our Markets 74 Sustainability 115 Balance Sheets Award highlights 20 Chairman’s Statement Committee Report 116 Statement of Changes 22 Chief Executive’s 76 Directors’ Remuneration in Equity Review Report 117 Statement of Cash Flows 26 Operating Review 98 Directors’ Report 118 Accounting Policies 48 Financial Review 104 Statement of Directors’ 123 Notes to the Financial 52 Risk -

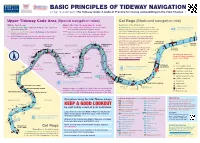

Upper Tideway (PDF)

BASIC PRINCIPLES OF TIDEWAY NAVIGATION A chart to accompany The Tideway Code: A Code of Practice for rowing and paddling on the Tidal Thames > Upper Tideway Code Area (Special navigation rules) Col Regs (Starboard navigation rule) With the tidal stream: Against either tidal stream (working the slacks): Regardless of the tidal stream: PEED S Z H O G N ABOVE WANDSWORTH BRIDGE Outbound or Inbound stay as close to the I Outbound on the EBB – stay in the Fairway on the Starboard Use the Inshore Zone staying as close to the bank E H H High Speed for CoC vessels only E I G N Starboard (right-hand/bow side) bank as is safe and H (right-hand/bow) side as is safe and inside any navigation buoys O All other vessels 12 knot limit HS Z S P D E Inbound on the FLOOD – stay in the Fairway on the Starboard Only cross the river at the designated Crossing Zones out of the Fairway where possible. Go inside/under E piers where water levels allow and it is safe to do so (right-hand/bow) side Or at a Local Crossing if you are returning to a boat In the Fairway, do not stop in a Crossing Zone. Only boats house on the opposite bank to the Inshore Zone All small boats must inform London VTS if they waiting to cross the Fairway should stop near a crossing Chelsea are afloat below Wandsworth Bridge after dark reach CADOGAN (Hammersmith All small boats are advised to inform London PIER Crossings) BATTERSEA DOVE W AY F A I R LTU PIER VTS before navigating below Wandsworth SON ROAD BRIDGE CHELSEA FSC HAMMERSMITH KEW ‘STONE’ AKN Bridge during daylight hours BATTERSEA -

International Pathway Programmes 2019/20

International Pathway Programmes 2019/20 London’s Campus University roehampton.ac.uk/pathway University of Roehampton Contents Welcome 4 Why Roehampton? 6 Our campus 9 Studying at Roehampton 10 Campus map 12 Supporting you 14 Free London 18 London’s campus university 20 Living costs 22 Sport at Roehampton 24 Your Students’ Union 26 Accommodation 28 Arriving at Roehampton 30 Pre-Sessional English 32 The Pathway College is a partnership between the University of Roehampton and QA Higher International Foundation Education – a UK Higher Education provider. The pathway programmes are validated by the Programme 34 University of Roehampton and taught by QA Higher Education. The University of Roehampton and QA Higher Education are committed to being equal Progression options 36 opportunities education providers and will therefore make reasonable adjustments for disabled applicants and students. How to apply 40 The information given in this publication is accurate at the time of going to print in March 2019 Our location and contacts 42 and the University of Roehampton and QA Higher Education will use all reasonable efforts to deliver the programmes as described. The University and QA Higher Education reserve the right to withdraw or change the programmes or programme combinations included in this prospectus. These changes will only be made as a result of UK legal compliance, minimum student number requirements or for course validation reasons and applicants will be contacted by the University or QA Higher Education in the instance of these changes occurring. Please check the website for up-to-date information on our programmes: roehampton.ac.uk/pathway 2 3 roehampton.ac.uk/pathway University of Roehampton Welcome At Roehampton, we believe passionately in the benefits of a university education undertaken away from your home country. -

LOW EMISSION BUS ZONES: EVALUATION of the FIRST SEVEN ZONES November 2018

LOW EMISSION BUS ZONES: EVALUATION OF THE FIRST SEVEN ZONES November 2018 LOW EMISSION BUS ZONES: EVALUATION OF THE FIRST SEVEN ZONES COPYRIGHT Greater London Authority November 2018 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk More London London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4000 minicom 020 7983 4458 ISBN Photographs © Copies of this report are available from www.london.gov.uk LOW EMISSION BUS ZONES: EVALUATION OF THE FIRST SEVEN ZONES 3 Introduction In August 2016 the Mayor of London announced London’s first Low Emission Bus Zone programme. A total of twelve Low Emission Bus Zones are planned across London. This report reviews the progress to date now that over half of the Low Emission Bus Zones are in operation. All the remaining zones will be complete by the end of 2019. What is a Low Emission Bus Zone? Low Emission Bus Zones use buses with top-of-the-range engines and exhaust systems that meet or exceed the highest Euro VI emissions standards1. The zones have been prioritised in the worst air quality hotspots outside central London where buses contribute significantly to road transport emissions. All TfL buses operating in the central London Ultra Low Emission Zone will meet the Euro VI standard from April 2019. The first zone was introduced along Putney High Street in March 2017 and was followed by a second Low Emission Bus Zone between Brixton Road and Streatham High Road in December 2017. All 12 zones are set to be completed in 2019 and form a central part of the Mayor's far- reaching plans for a drastic clean-up of London's toxic air. -

The London Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment 2017

The London Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment 2017 Part of the London Plan evidence base COPYRIGHT Greater London Authority November 2017 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk More London London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 Copies of this report are available from www.london.gov.uk 2017 LONDON STRATEGIC HOUSING LAND AVAILABILITY ASSESSMENT Contents Chapter Page 0 Executive summary 1 to 7 1 Introduction 8 to 11 2 Large site assessment – methodology 12 to 52 3 Identifying large sites & the site assessment process 53 to 58 4 Results: large sites – phases one to five, 2017 to 2041 59 to 82 5 Results: large sites – phases two and three, 2019 to 2028 83 to 115 6 Small sites 116 to 145 7 Non self-contained accommodation 146 to 158 8 Crossrail 2 growth scenario 159 to 165 9 Conclusion 166 to 186 10 Appendix A – additional large site capacity information 187 to 197 11 Appendix B – additional housing stock and small sites 198 to 202 information 12 Appendix C - Mayoral development corporation capacity 203 to 205 assigned to boroughs 13 Planning approvals sites 206 to 231 14 Allocations sites 232 to 253 Executive summary 2017 LONDON STRATEGIC HOUSING LAND AVAILABILITY ASSESSMENT Executive summary 0.1 The SHLAA shows that London has capacity for 649,350 homes during the 10 year period covered by the London Plan housing targets (from 2019/20 to 2028/29). This equates to an average annualised capacity of 64,935 homes a year. -

Putney Heath, Proposed LIGS London Borough of Wandsworth, TQ 231 732 (Best Exposure) Ownership: Local Authority

Guide to London’s Geological Sites GLA 25: Putney Heath, Proposed LIGS London Borough of Wandsworth, TQ 231 732 (best exposure) Ownership: Local Authority. Open access. Putney Heath Putney Heath has been selected as a site of local importance for its exposures of Black Park Gravel. The area cited is a plateau on the top of the wider parkland area which becomes Wimbledon Common to the south. This plateau also extends into adjacent Richmond Park to the east, separated by the valley cut by the Beverley Brook which flows north into the Thames. Black Park Gravel The Black Park Gravel is the oldest of the Thames Terraces, deposited immediately after the retreat of the Anglian Ice Sheet about 400,000 years ago (Oxygen Isotope Stage 12-11). On Putney Heath the height of the top of the exposure is 53 m which falls within the range of Black Park Gravel recorded from elsewhere (eg Hornchurch Railway Cutting SSSI, GLA19, and Mark’s Warren Quarry Complex,GLA 37, in East London) (see BGS Special Memoir, p. 61-64 and reference 1 below). At Hornchurch it overlies the glacial till abandoned by the retreating ice sheet of the biggest of the Ice Age glaciations, the Anglian, the only one to extend to London, although it never reached as far south as Putney. The graveI contains a larger proportion of exotic fragments than the later gravels as a direct consequence of its proximity to the icesheet that carried clasts from all over the country. As in the other Thames gravels by far the greatest proportion of the pebbles are flints.