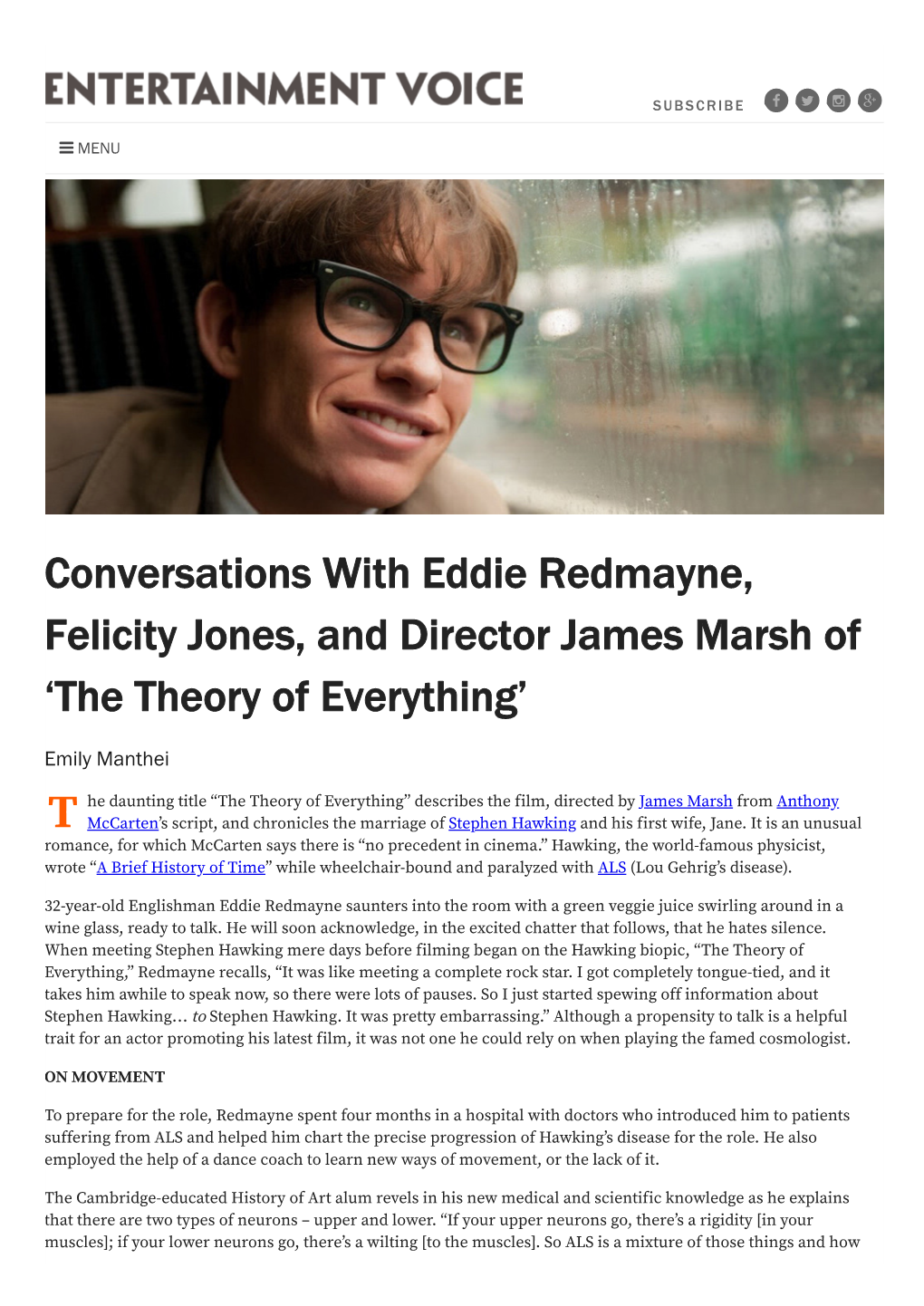

Conversations with Eddie Redmayne, Felicity Jones, and Director James Marsh of ‘The Theory of Everything’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entertainment Business Supplemental Information Three Months Ended September 30, 2015

Entertainment Business Supplemental Information Three months ended September 30, 2015 October 29, 2015 Sony Corporation Pictures Segment 1 ■ Pictures Segment Aggregated U.S. Dollar Information 1 ■ Motion Pictures 1 - Motion Pictures Box Office for films released in North America - Select films to be released in the U.S. - Top 10 DVD and Blu-rayTM titles released - Select DVD and Blu-rayTM titles to be released ■ Television Productions 3 - Television Series with an original broadcast on a U.S. network - Television Series with a new season to premiere on a U.S. network - Select Television Series in U.S. off-network syndication - Television Series with an original broadcast on a non-U.S. network ■ Media Networks 5 - Television and Digital Channels Music Segment 7 ■ Recorded Music 7 - Top 10 best-selling recorded music releases - Upcoming releases ■ Music Publishing 7 - Number of songs in the music publishing catalog owned and administered as of March 31, 2015 Cautionary Statement Statements made in this supplemental information with respect to Sony’s current plans, estimates, strategies and beliefs and other statements that are not historical facts are forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to, those statements using such words as “may,” “will,” “should,” “plan,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “estimate” and similar words, although some forward- looking statements are expressed differently. Sony cautions investors that a number of important risks and uncertainties could cause actual results to differ materially from those discussed in the forward-looking statements, and therefore investors should not place undue reliance on them. Investors also should not rely on any obligation of Sony to update or revise any forward-looking statements, whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise. -

Man on Wire Discussion Guide

www.influencefilmclub.com Man on Wire Discussion Guide Director: James Marsh Year: 2008 Time: 94 min You might know this director from: Project Nim (2011) Shadow Dancer (2012) The King (2005) FILM SUMMARY MAN ON WIRE is the story of French tightrope walker Philippe Petit who, on August 7, 1974, broke into the newly constructed Twin Towers of Manhattan. After months of painstaking preparations, he managed to enter the buildings during the night and string a wire between the two towers. For the next 45 minutes, Philippe Petit walked, danced, kneeled, and laid down on the wire - an expeirence he had dreamt of ever since he read about the Twin Towers six years before. Using contemporary interviews, archival footage, and Philippe’s own creations, this film tells the story of Philippe’s previous walks between towers such as the Notre Dame and the Sydney Harbour Bridge. Viewers learn about his passions, his friendships, and how he accomplished his Twin Towers walk, from getting the wire into the towers and hiding from guards to mounting the wire and taking the first step. The result is a story of daring, beauty, dedication to the point of insanity, loyalty and heartbreak, and the firm belief that nothing is impossible. Discussion Guide Man on Wire 1 www.influencefilmclub.com FILM THEMES On the surface, MAN ON WIRE may appear to be about one man’s determination to achieve his dream, but the story reveals a lot about human nature, from friendship and loyalty to dreaming beyond the norm “I must be a and achieving the impossible. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Super Active Film Making by James Marsh

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Super Active Film Making by James Marsh James Marsh is the author of super.activ Film Making (0.0 avg rating, 0 ratings, 0 reviews), Film Making (0.0 avg rating, 0 ratings, 0 reviews, published... Nov 07, 2014 · James Marsh: In terms of scale of filmmaking and resources, it absolutely was and it was so welcome to have a bigger budget. I’ve always worked very efficiently on small budgets, both in ... May 30, 2013 · Now, 50 Marsh consistently crafts films that viscerally delve into the human experience. His deft navigation between documentary and feature have inspired comparisons to Werner Herzog. Marsh’s third narrative feature, Shadow Dancer, is no different. Set in Belfast in the early ’90s, the morose, slow-burning thriller eschews political intricacies and instead focuses on Collette McVeigh (an vulnerable and nuanced Andrea Riseborough), a single mother and member of an active … Project Nim, is also directed by Marsh, but it doesn't have the same suspense that that film had. Man on Wire kept me interested in how Petit was able to achieve his goal, he was a very charismatic figure, and on the other hand Project Nim was kind of slow paced and didn't have any interesting characters…3.6/5(3K)Director: James MarshProduce Company: BBC Films, Red Box Films, Passion PicturesTeam of Artists Transformed Eddie Redmayne Into Stephen ...https://variety.com/2014/artisans/production/large...Nov 06, 2014 · He starts film at 21, an able- bodied, fresh-faceed, young man with whole world in front of him. -

Julianne Moore Stephen Dillane Eddie Redmayne

JULIANNE MOORE STEPHEN DILLANE EDDIE REDMAYNE ELENA ANAYA Directed By Tom Kalin UNAX UGALDE Screenplay by Howard A. Rodman Based on the book by Natalie Robins & Steven M. L. Aronson BELÉN RUEDA HUGH DANCY Julianne Moore, Stephen Dillane, Eddie Redmayne Elena Anaya, Unax Ugalde, Belén Rueda, Hugh Dancy CANNES 2007 Directed by Tom Kalin Screenplay Howard A. Rodman Based on the book by Natalie Robins & Steven M.L Aronson FRENCH / INTERNATIONAL PRESS DREAMACHINE CANNES 4th Floor Villa Royale 41 la Croisette (1st door N° 29) T: + 33 (0) 4 93 38 88 35 WORLD SALES F: + 33 (0) 4 93 38 88 70 DREAMACHINE CANNES Magali Montet 2, La Croisette, 3rd floor M : + 33 (0) 6 71 63 36 16 T : + 33 (0) 4 93 38 64 58 E: [email protected] F : + 33 (0) 4 93 38 62 26 Gordon Spragg M : + 33 (0) 6 75 25 97 91 LONDON E: [email protected] 24 Hanway Street London W1T 1UH US PRESS T : + 44 (0) 207 290 0750 INTERNATIONAL HOUSE OF PUBLICITY F : + 44 (0) 207 290 0751 info@hanwayfilms.com CANNES Jeff Hill PARIS M: + 33 (0)6 74 04 7063 2 rue Turgot email: [email protected] 75009 Paris, France T : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0370 Jessica Uzzan F : + 33 (0) 1 4970 0371 M: + 33 (0)6 76 19 2669 [email protected] email: [email protected] www.dreamachinefilms.com Résidence All Suites – 12, rue Latour Maubourg T : + 33 (0) 4 93 94 90 00 SYNOPSIS “Savage Grace”, based on the award winning book, tells the incredible true story of Barbara Daly, who married above her class to Brooks Baekeland, the dashing heir to the Bakelite plastics fortune. -

Top 30 Films

March 2013 Top 30 Films By Eddie Ivermee Top 30 films as chosen by me, they may not be perfect or to everyone’s taste. Like all good art however they inspire debate. Why Do I Love Movies? Eddie Ivermee For that feeling you get when the lights get dim in the cinema Because of getting to see Heath Ledger on the big screen for the final time in The Dark Knight Because of Quentin Tarentino’s knack for rip roaring dialogue Because of the invention of the steadicam For saving me from the drudgery of nightly weekly TV sessions Because of Malik’s ability to make life seem more beautiful than it really is Because of Brando and Pacino together in The Godfather Because of the amazing combination of music and image, e.g. music in Jaws Because of the invention of other worlds, see Avatar, Star Wars, Alien etc. For making us laugh, cry, sad, happy, scared all in equal measure. For the ending of the Shawshank Redemption For allowing Jim Carey lose during the 1990’s For arranging a coffee date on screen of De Niro an Pacino For allowing Righteous Kill to go straight to DVD so I could turn it off For taking me back in time with classics like Psycho, Wizard of Oz ect For making dreams become reality see E.T, The Goonies, Spiderman, Superman For allowing Brad Pitt, Michael Fassbender, Tom Hardy and Joesph Gordon Levitt ply their trade on screen for our amusement. Because of making people Die Hard as Rambo strikes with a Lethal Weapon because he is a Predator who is also Rocky. -

Pocket Product Guide 2006

THENew Digital Platform MIPTV 2012 tm MIPTV POCKET ISSUE & PRODUCT OFFILMGUIDE New One Stop Product Guide Search at the Markets Paperless - Weightless - Green Read the Synopsis - Watch the Trailer BUSINESSC onnect to Seller - Buy Product MIPTVDaily Editions April 1-4, 2012 - Unabridged MIPTV Product Guide + Stills Cher Ami - Magus Entertainment - Booth 12.32 POD 32 (Mountain Road) STEP UP to 21st Century The DIGITAL Platform PUBLISHING Is The FUTURE MIPTV PRODUCT GUIDE 2012 Mountain, Nature, Extreme, Geography, 10 FRANCS Water, Surprising 10 Francs, 28 Rue de l'Equerre, Paris, Delivery Status: Screening France 75019 France, Tel: Year of Production: 2011 Country of +33.1.487.44.377. Fax: +33.1.487.48.265. Origin: Slovakia http://www.10francs.f - email: Only the best of the best are able to abseil [email protected] into depths The Iron Hole, but even that Distributor doesn't guarantee that they will ever man- At MIPTV: Yohann Cornu (Sales age to get back.That's up to nature to Executive), Christelle Quillévéré (Sales) decide. Office: MEDIA Stand N°H4.35, Tel: + GOOD MORNING LENIN ! 33.6.628.04.377. Fax: + 33.1.487.48.265 Documentary (50') BEING KOSHER Language: English, Polish Documentary (52' & 92') Director: Konrad Szolajski Language: German, English Producer: ZK Studio Ltd Director: Ruth Olsman Key Cast: Surprising, Travel, History, Producer: Indi Film Gmbh Human Stories, Daily Life, Humour, Key Cast: Surprising, Judaism, Religion, Politics, Business, Europe, Ethnology Tradition, Culture, Daily life, Education, Delivery Status: Screening Ethnology, Humour, Interviews Year of Production: 2010 Country of Delivery Status: Screening Origin: Poland Year of Production: 2010 Country of Western foreigners come to Poland to expe- Origin: Germany rience life under communism enacted by A tragicomic exploration of Jewish purity former steel mill workers who, in this way, laws ! From kosher food to ritual hygiene, escaped unemployment. -

Larry D. Horricks Society of Motion Picture Stills Photographers

Larry D. Horricks Society of Motion Picture Stills Photographers www.larryhorricks.com Feature Films: Spaceman of Bohemia – Netflix – Johan Renck Director Cast – Adam Sandler, Carey Mulligan Producers: Michael Parets, Max Silva, Ben Ormand, Barry Bernardi White Bird – Lionsgate – Marc Forster Director (Unit + Specials_ Cast: Gillian Anderson ,Helen Mirren, Ariella Glaser, Orlando Schwerdt Producers: Marc Forster, Tod Leiberman, David Hoberman, Raquel J. Palacio Oslo – Dreamworks Pictures / Amblin / HBO / Marc Platt Prods.– Bart Sher Director (Unit + Specials) Cast: Ruth Wilson, Andrew Scott, Jeff Wilbusch,Salim Dau, Producers: Steven Spielberg, Kristie Macosko Krieger, Marc Platt, Cambra Overend, Mark Taylor Atlantic 437 – Netflix. Ratpack Entertainment – Director Peter Thorwath Producers: Chritian Becker,Benjamin Munz The Dig – Netflix, Magnolia Mae Films – Simon Stone Director Cast: Ralph Fiennes, Carey Mulligan, Lily James, Ken Stott, Johnny Flynn Producers: Gabrielle Tana, Carolyn Marks Blackwood, Redmond Morris A Boy Called Christmas – Netflix – Gil Kenan Director (Unit + Specials) Cast: Sally Hawkins, Kristen Wiig,Maggie Smith, Jim Broadbent, Toby Jones, Michiel Huisman, Harry Lawful Producers: Graham Broadbent, Pete Czernin, Kevan Van Thompson Minamata - Metalwork Pictures /HanWay Films / MGM - Andrew Levitas Director (Unit + Specials) Cast: Johnny Depp, Bill Nighy, Minami, Hiro Sanada, Ryo Kase, Sato Tadenobu, Jun Kunimura Producers: Andrew Levitas,Gabrielle Tana, Jason Foreman, Johnny Depp, Sam Sarkar, Stephen Deuters, Kevan -

Press Release

News Release Wednesday 26 July 2017 NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY COMMISSIONS NEW PHOTOGRAPH OF THIS IS ENGLAND AND SKINS ACTOR JACK O’CONNELL AS PART OF THE JOHN KOBAL NEW WORK AWARD Jack O’Connell by Tereza Červeňová, 2017 © National Portrait Gallery, London A striking newly-commissioned photograph of actor Jack O’Connell has been commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery, it was announced today, Wednesday 26 July 2017, coinciding with his West End starring role in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof with Sienna Miller opening this week. The portrait, taken by photographer Tereza Červeňová, was commissioned through the John Kobal New Work Award, a prize awarded annually to a photographer under thirty-five whose work is selected for display in the Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery. The London-based Slovakian photographer Tereza Červeňová won the John Kobal New Work Award commission following her selection as part of the Taylor Wessing Photographic Portrait Prize 2015 exhibition, and was invited to photograph the actor Jack O’Connell in March 2017. Červeňova’s photograph of Jack O’Connell was taken at his family home in Derby, and challenges the ‘angry youth’ image associated with acting roles such as his film debut as the blue-collar teenager Pukey Nicholls in the 2006 coming-of-age drama This is England, a young murderer in the British horror Eden Lake, a drug addict in Harry Brown and James Cook in the teen drama Skins. Shown with a hint of vulnerability and wearing a tee-shirt in a garden, O’Connell is reflected through a window as Červeňova creates a semi-abstracted composition playing with light and lines as the actor’s torso apparently emerges intertwined with panels of a wooden fence. -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

Oscar Ballot Oscar Ballot

AND THE AND THE OSCAR OSCAR GOES TO. GOES TO. THE 2015 THE 2015 OSCAR BALLOT OSCAR BALLOT ACTOR IN A LEADING ROLE ACTOR IN A LEADING ROLE BEST PICTURE BEST PICTURE Steve Carell (Foxcatcher) Steve Carell (Foxcatcher) American Sniper Bradley Cooper (American Sniper) American Sniper Bradley Cooper (American Sniper) Birdman Benedict Cumberbatch (The Imitation Game) Birdman Benedict Cumberbatch (The Imitation Game) Boyhood Michael Keaton (Birdman) Boyhood Michael Keaton (Birdman) The Grand Budapest Hotel Eddie Redmayne (The Theory of Everything) The Grand Budapest Hotel Eddie Redmayne (The Theory of Everything) The Imitation Game The Imitation Game Selma Selma ANIMATED FEATURE The Theory of Everything The Theory of Everything ANIMATED FEATURE Whiplash Big Hero 6 Whiplash Big Hero 6 The Boxtrolls The Boxtrolls How to Train Your Dragon 2 How to Train Your Dragon 2 ACTRESS IN A LEADING ROLE Son of the Sea ACTRESS IN A LEADING ROLE Son of the Sea The Tale of Princess Kaguya Marion Cotillard (Two Days, One Night) Marion Cotillard (Two Days, One Night) The Tale of Princess Kaguya Felicity Jones (The Theory of Everything) Felicity Jones (The Theory of Everything) PRODUCTION DESIGN Julianne Moore (Still Alice) Julianne Moore (Still Alice) PRODUCTION DESIGN Rosamund Pike (Gone Girl) THe Grand Budapest Hotel Rosamund Pike (Gone Girl) THe Grand Budapest Hotel Reese Witherspoon (Wild) The Imitation Game Reese Witherspoon (Wild) The Imitation Game Interstellar Interstellar Into the Woods Into the Woods ACTOR IN A SUPPORTING ROLE ACTOR IN A SUPPORTING ROLE Mr. Turner Mr. Turner Robert Duvall (The Judge) Robert Duvall (The Judge) Ethan Hawke (Boyhood) Ethan Hawke (Boyhood) COSTUME DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN Edward Norton (Birdman) Edward Norton (Birdman) Mark Ruffalo (Foxcatcher) The Grand Budapest Hotel Mark Ruffalo (Foxcatcher) The Grand Budapest Hotel J.K. -

SHIRCORE Jenny

McKinney Macartney Management Ltd JENNY SHIRCORE - Make-Up and Hair Designer 2003 Women in Film Award for Best Technical Achievement Member of The Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences THE DIG Director: Simon Stone. Producers: Murray Ferguson, Gabrielle Tana and Ellie Wood. Starring: Lily James, Ralph Fiennes and Carey Mulligan. BBC Films. BAFTA Nomination 2021 - Best Make-Up & Hair KINGSMAN: THE GREAT GAME Director: Matthew Vaughn. Producer: Matthew Vaughn. Starring: Ralph Fiennes and Tom Holland. Marv Films / Twentieth Century Fox. THE AERONAUTS Director: Tom Harper. Producers: Tom Harper, David Hoberman and Todd Lieberman. Starring: Felicity Jones and Eddie Redmayne. Amazon Studios. MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS Director: Josie Rourke. Producers: Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner and Debra Hayward. Starring: Margot Robbie, Saoirse Ronan and Joe Alwyn. Focus Features / Working Title Films. Academy Award Nomination 2019 - Best Make-Up & Hairstyling BAFTA Nomination 2019 - Best Make-Up & Hair THE NUTCRACKER & THE FOUR REALMS Director: Lasse Hallström. Producers: Mark Gordon, Larry J. Franco and Lindy Goldstein. Starring: Keira Knightley, Morgan Freeman, Helen Mirren and Misty Copeland. The Walt Disney Studios / The Mark Gordon Company. WILL Director: Shekhar Kapur. Exec. Producers: Alison Owen and Debra Hayward. Starring: Laurie Davidson, Colm Meaney and Mattias Inwood. TNT / Ninth Floor UK Productions. Gable House, 18 – 24 Turnham Green Terrace, London W4 1QP Tel: 020 8995 4747 E-mail: [email protected] www.mckinneymacartney.com VAT Reg. No: 685 1851 06 JENNY SHIRCORE Contd … 2 BEAUTY & THE BEAST Director: Bill Condon. Producers: Don Hahn, David Hoberman and Todd Lieberman. Starring: Emma Watson, Dan Stevens, Emma Thompson and Ian McKellen. Disney / Mandeville Films. -

Interview-With-Felicity-Jones

BURNING BRIGHT No longer the next big thing, with a clutch of films coming out, Felicity Jones is now getting all the attention she deserves. By Jane Cornwell. sl • 8 ometimes, when being Felicity a headache, visions and amnesia. saleswoman who met while working on SJones gets too much, Felicity Jones “I HAVEN’T Jones’ character Brooks, a lab-coat- the local newspaper and split when she likes to wander down to Hampstead wearing environmentalist, is quickly was three. Felicity and her elder brother, Heath, the ancient park that is one of HAD TO Langdon’s right-hand woman, racing a $lm editor whose wife hails from London’s best-loved green spaces. !en, with him across Europe to a) help him Brisbane (“Briz Vegas? Ha! !at’s so with her back against the trunk of her SACRIFICE recover his memory and b) quash a funny”), were brought up by their mum. favourite old oak tree, she’ll take out deadly virus aimed at wiping out half “I was raised to live in the moment.” her sketchpad and draw. TOO MUCH the world’s (over) population. Currently splitting her time between “!ey tend to be slightly abstract, Brooks isn’t what she seems, of course. north London and Brooklyn, New York, usually terrible pieces of artistic Nothing is. !is time the clues are to be Jones’ crisp vowels belie her consonant- endeavour,” says the petite actress, PRIVACY found in Dante Alighieri’s epic 14th dropping Brummie origins, which are 32, sitting in a suite in a posh London century poem about his journey through obvious, she says, once she’s had a drink hotel and looking every inch the English AND hell, which Langdon and Brooks pore or three and o"er scope “to be teased if rose in a royal-blue jumpsuit with pu" over in galleries and on laptops, and I ever got a big head”.