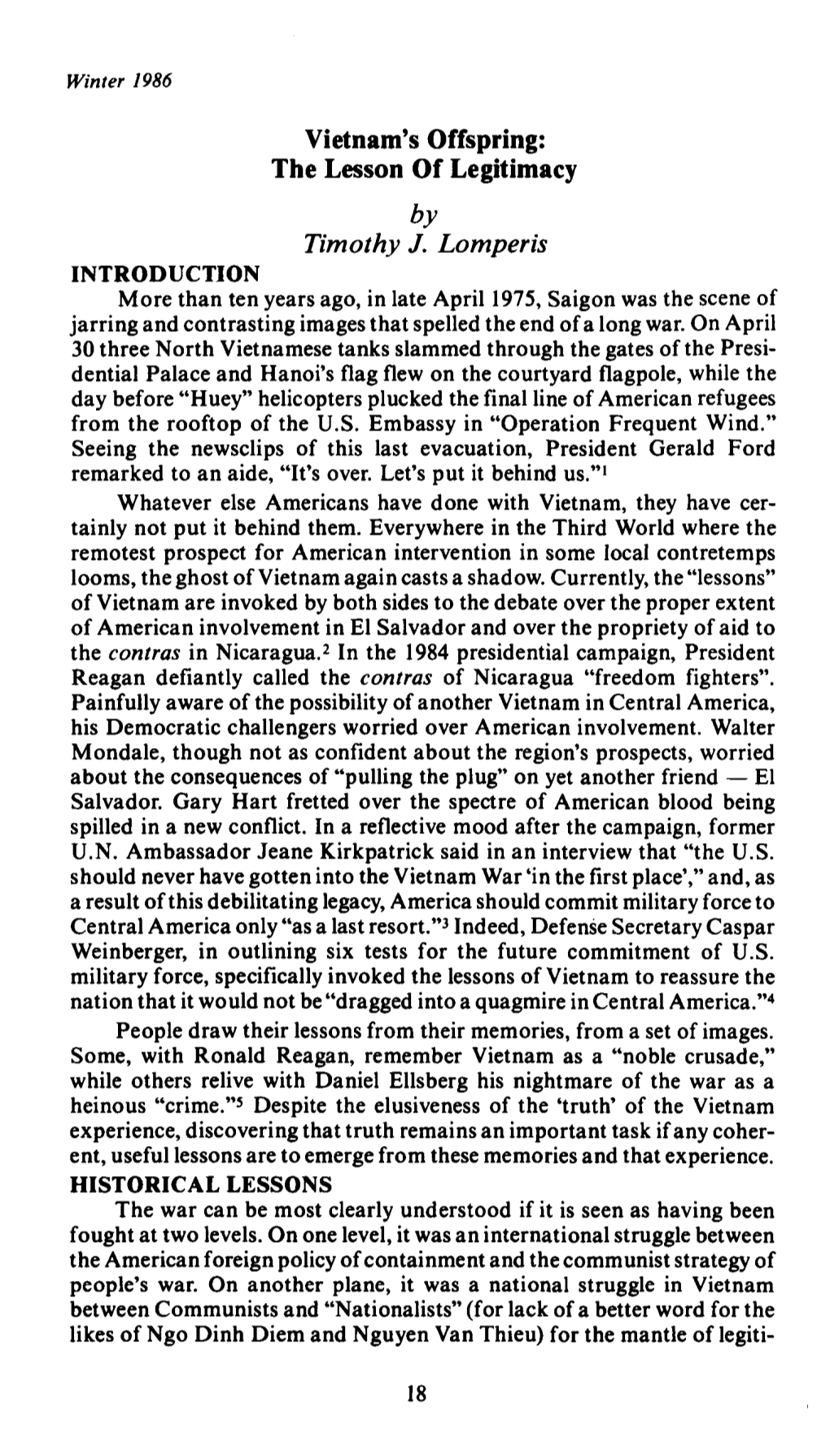

Vietnam's Offspring: the Lesson of Legitimacy by Timothy J. Lomperis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lyndon B. Johnson Film Collection

Johnson, Lyndon B. (1908-1973.) Film Collection, 1958-1969. Special Collections Department/Long Island Studies Institute Contact Information: Special Collections Department Axinn Library, Room 032 123 Hofstra University Hempstead, NY 11549 Phone: (516) 463-6411, or 463-6404 Fax: (516) 463-6442 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.hofstra.edu/Libraries/SpecialCollections FILMING LBJ: A SPECIAL COLLECTION FROM WHITE HOUSE NAVAL PHOTOGRAPHER COMMANDER THOMAS ATKINS, 1963-1969 The Lyndon B. Johnson presidency is unique in its collection of recordings of the chief executive’s activities. In the 1960s, the White House Naval Photographic Unit (NPC) began producing films that highlighted special presidential trips, visits, and events. Commander Thomas Atkins produced these films for the NPC, starting in 1963 in the John F. Kennedy administration and continuing through the Johnson years. About 43 of the 70+ films are available for viewing on the Lyndon B. Johnson Library’s YouTube channel at https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL853F6EAB74B64D1D . Hofstra University’s Peter S. Kalikow Center for the Study of the American Presidency has a full digitized set of the Atkins films, which are available for research in the Joan and Donald E. Axinn Library’s Special Collections room. In the summer of 2013, Ms. Nancy Lindemeyer (who, along with her husband, Robert Lindemeyer, served with Commander Atkins in the Navy) contacted Hofstra on behalf of the Atkins family to see if the Kalikow Center might be a suitable repository for the collection. Thanks to the generosity of the Atkins family and the cheerful, unstinting efforts of the Lindemeyers, the original 16 mm films were transferred to DVDs and became part of Hofstra’s holdings in 2015. -

Eric Hoffer: Implications for a Social Theory of Communication

ERIC HOFFER: IMPLICATIONS FOR A SOCIAL THEORY OF COMMDNICATION by Jane Ann Fisher B.A., University of South Dakota, 1967 Submitted to the Department of Speech and Drama and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Redacted Signature Instructor in charge Redacted Signature For the Department November, 1970 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many individuals have contributed to the progress of this research project, and it is impossible for me to ac- knowledge them all. However, there are certain people who have been especially instrumental to my completion of the study. The idea for this paper first occurred to me when I was taking a course in persuasion from Professor Donn W. Parson. He suggested to me that Eric Hoffer's philosophy had not been analyzed from the perspective of communication and that this might be fruitful ground for research. In subsequent courses, Professor Parson introduced me to the theories of the symbolic interactionists and, thus, I developed the theoretical approach which I have used in this study--that of the social theory of communication. I am grateful for this background as well as the help and advice which Professor Parson has given me while serving as my advisor. I also would like to thank Professors Berg and Hamlin, members of my thesis committee, for their support of my efforts. Thanks must go to the many graduate students at the University of Kansas who have given needed criticism as well as advice. But most importantly, without the en- couragement of my husband and parents, this project would never have reached completion. -

True Believer 1St Edition Ebook Free Download

TRUE BELIEVER 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nicholas Sparks | 9781455571666 | | | | | True Believer 1st edition PDF Book Hoffer maintained some prominence for thirty years, much loved on the Right for bringing to popular recognition that Communism was and is a religion as much as a political movement. More Details. I cannot count the times that a smirk has crossed my face recently when people have compared the mild, political edginess between today's political correctness and populism to the heady days of Germany's Weimar Republic and the bloody street fights between National Socialists and Marxists. The substitutes would be pride instead of self-confidence, memberships in a collective whole like a mass movement, absolute certainty instead of understanding. Eric Hoffer. He instructs, he tells parables, he shares wisdom. It is a book of thoughts, and it does not shy away from half-truths so long as they seem to hint as a new approach and help to formulate new questions. Now, if the young lovers are to have any kind of future at all, Jeremy must make a difficult choice: return to the life he knows, or do something he could never do before-take a giant leap of faith. The movements and rituals hide people's shortcomings from themselves. Quick Copy View. More information about this seller Contact this seller 4. Average rating 4. Stock Image. Early in the book Hoffer identifies many true believers as those who seek "substitutes either for the whole self or for the elements which make life bearable and which they cannot evoke out of their individual resources. -

Thinking Things Over

- : THE WALL STREET JOURN ,, One of these is Henry Hazlitt, currently • · ·.:~·~ · approaching his ninetieth year with no di·. , munition of mind and spirit. He first gained recognition as a literary critic (I still cherish his "Anatomy. of Criticism," :·;:'Thinking read in my college days) . He served on ·The Wall Street Journal before its present editors were born and was for a time an editorial writer on both the old New York Thing~ Herald-Tribune and the New York Times. Then some 40 years ago he wrote a .·· Over. · small volume, "Economics In One ·Les· son," which is almost what its title states. (\La:. ')_f ., ~ ~3 Anyway, there Is no better introduction to the fallacies of socialist economics or the ~~ Ve~nt ROyster..;..._.~ merits of the marketplace as a regulator of man's economic labors. The Half-Forgotten Men · Perhaps the oddest of those sowers of I'm not sure tliat "conservative,.. the seeds was Eric Hoffer, another who died word so often applied, is the right one for this year. What made him seem Odd was the mood of the country these past few that he was a "man of the people" who years. I am sure we are seeing a revolt worked all his life as .a day laborer and against the politics that brought us re who had· no formal education. Not at all peated inflation, rising taxes,· neglect of the sort of background from which you our defenses and a growing intrusion of would expect an intellectual to spring, es· government into everyone's life. It's a pecially one to take up cudgels against the moOd no politician, Democratic or Republi· collectivist political philosophy that once can, can afford to ignore. -

John F. Beck Papers (C4360)

John F. Beck Papers (C4360) Collection Number: C4360 Collection Title: John F. Beck Papers Dates: 1952-1998 Creator: Beck, John F., 1916-2007 Abstract: Correspondence, research material, CBS scripts, reports, transcripts of television productions and videotaped interview of a CBS Television producer, writer and director of the 1960s. Collection Size: 1.7 cubic feet, 1 video cassette (55 folders) Language: Collection materials are in English. Repository: The State Historical Society of Missouri Restrictions on Access: Collection is open for research. This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Columbia. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. Collections may be viewed at any research center. Restrictions on Use: The Donor has given and assigned to the University all rights of copyright, which the Donor has in the Materials and in such of the Donor’s works as may be found among any collections of Materials received by the University from others. Preferred Citation: [Specific item; box number; folder number] John F. Beck Papers (C4360); The State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center-Columbia [after first mention may be abbreviated to SHSMO-City]. Donor Information: The papers were donated to the University of Missouri by John F. Beck on August 10, 1999 (Accession No. 5824) Processed by: Processed by John Konzal on July 2, 2018. (C4360) John F. Beck Papers Page 2 Historical Note: John Frederick Beck was born on May 7, 1916, to John and Kathryn Beck. In the 1930s, he attended the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism, graduating in 1938. -

Eric Hoffer, Philosopher for the People

because it reflected badly on me and censorship, and financial obligations. Opus Dei; Opus Dei places its members Despite this, Opus Dei asserts that there Tammy DiNicola entered Opus Dei in in a position where they feel obligated is no secrecy, and that indeed Opus Dei 1988 as a Boston College sophomore. to breach the Eighth Commandment. is "an open book." Those of us who have She left Opus Dei in 1990 and is one When pressed by their families, Opus Dei been wounded and deceived by Opus Dei of the founders of the Opus Dei Aware- members will often lie or practice mental wish only that they would reform their ness Network, Inc., P.O. Box 4333, reservation, not only about when they deceptive practices and allow members Pittsfield, MA 01202. ODAN has a joined, but about other aspects of Opus to join freely without subtle pres- wealth of information on Opus Dei and Dei life such as corporal mortification, sures. its practices. composing The Organization Man, his Eric Hoffer, formidable and troubled study of that complacent social conformism, which Philosopher for the People Norman Vincent Peale, author of The Power of Positive Thinking, considered a sign of Our Maker's benefaction. Meanwhile, Korea was in flames, the Richard Arnold Cold War was deepening, and Joseph McCarthy set out to rescue an otherwise Fr he son of working-class Alsatian pristine body politic from massive immigrants, Eric Hoffer was born communist infiltration. Hoffer's book in New York City on July 25, 1902. He The True Believer fit no Manichean was orphaned at age five and stricken scheme. -

Eisenhower, Dwight D.: Post-Presidential Papers, 1961-69

EISENHOWER, DWIGHT D.: POST-PRESIDENTIAL PAPERS, 1961-69 1969 PRINCIPAL FILE Series Description This series contains correspondence that Dwight D. Eisenhower received during the last three months of his life as well as some letters and memos from staff in April and May 1969. Eisenhower spent the entire January to March period at Walter Reed. Robert Schulz, Eisenhower’s aide, responded to the bulk of the letters, cards, and telegrams written to Eisenhower and indicated to many correspondents that Eisenhower’s health problems made it impossible for him to make a personal response. Nonetheless, there are a limited number of letters from Eisenhower to individuals, including Harold Macmillan, Charles de Gaulle, Walter Cronkite, and Earl Warren. In March 1969 Eisenhower wrote a letter to Irving Berlin thanking him for the “wonderful melodies” he had created for everyone to enjoy. The series is divided into three subseries; the Subject Subseries, the Alphabetical Subseries, and the Bulk Mail Subseries. The first two subseries contain most of the correspondence and the last subseries contains the larger, bulky items staff did not want to mix with the correspondence. Besides cards and letters, some people sent Eisenhower gifts of books, poems, flowers, and candy. Some of the subjects covered in the correspondence include fund raising efforts for the Eisenhower College, the publication and sale of Eisenhower’s In Review, the Johns Hopkins Press project to published a selection of Eisenhower’s records, the National Railroad Museum and the Eisenhower locomotive and cars, and Eisenhower’s response to the John Birch Society and the book The Politician. -

Eric Hoffer Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt0n39n6dd No online items Register of the Eric Hoffer papers Finding aid prepared by David Jacobs Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2003 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Eric Hoffer papers 94057 1 Title: Eric Hoffer papers Date (inclusive): 1934-1996 Collection Number: 94057 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 146 manuscript boxes, 2 cubic foot boxes, 10 oversize boxes, 7 card file boxes, 1 painting(73.3 Linear Feet) Abstract: Speeches and writings, correspondence, reports, minutes, memoranda, printed matter, and audiovisual material relating to philosophy, social psychology, the nature of mass movements, social violence, the social role of intellectuals, and social conditions in the United States. Creator: Hoffer, Eric Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Video tapes (Boxes 144-146) may not be reproduced. Acquisition Information Materials were acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1994. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Eric Hoffer papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. 1898 Born, New York (?) 1920s-1930sWorked as migrant farm laborer and gold miner in California, Oregon, and Washington 1942 Began work as a longshoreman in San Francisco, California 1951 Author, The True Believer 1955 Author, The Passionate State of Mind 1963 Author, The Ordeal of Change 1967 Invited to the White House by President Lyndon B. -

American University Library Special Collections Finding Aid to The

American University Library Special Collections Finding Aid to the Papers of Edward Bliss, Jr. Processed by: Sonia Spurlock February 2011 VOLUME: 72.5 linear feet ACCESS: This collection is open to the public upon request. COPYRIGHT: Please consult the archivist for information about duplication or publishing of any materials from this collection. RELATED COLLECTIONS: Drew Pearson Papers and Merry-Go-Round Collections Laszlo Dosa Voice of America Science and Medicine Scripts TABLE OF CONTENTS: Biographical Note Scope and Content Note Provenance Processing Note Series Descriptions & Box and Folder Listing Biographical Note Edward “Ed” Bliss, Jr. was born on July 30, 1912 to Edward Lydston and May Bortz Bliss in Fuzhou, China. His father was a medical missionary and his mother was a teacher. After graduating from college in 1935, he worked as a print journalist and a news editor for several small newspapers in Columbus, Ohio. Bliss married Lois Arnette on August 26, 1940 with whom he had two children. In 1943, Bliss was hired by CBS to work the night shift. He was a producer and editor for Edward Murrow from 1945 to 1955. Bliss also served as an assistant to the president of CBS News in 1962 before becoming editor of “CBS Evening News with Walter Cronkite” in 1963. Bliss left CBS News in 1968 to establish the broadcast journalism program at the School of Communication at American University in Washington, D.C. He taught at American University until 1977. After retiring as a full professor, Bliss remained active as a news consultant for stations across the United States. -

The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements (Eric Hoffer) April 8, 2019

The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements (Eric Hoffer) April 8, 2019 Eric Hoffer was, Dwight Eisenhower said in 1952, his favorite phi- losopher. This endorsement made Hoffer, a self-educated San Francisco stevedore, famous. The True Believer is the book that Eisenhower gave all his friends. Read today, however, this book is mediocre, at best. It is the type of book that congratulates the reader while pretending to challenge him; it is a mirror that reflects to the reader what he wants to hear—especially for self-proclaimed “moderates” of flexible principle like Eisenhower. The True Believer is the Cream of Wheat of political books—you can taste anything you want in it, and if you add the right toppings yourself, you can be sure that you will be pleased. Hoffer was not only self-educated, he also manufactured his own life story. He claimed to be born in 1898 in the Bronx to Alsatian German immigrants, grown up there, and to have later lived on Skid Row in Los Angeles. The first records of him show up in the 1940s, when he started working on the Los Angeles docks, which he did for decades. Most of his backstory is probably false; he spoke with a Bavarian accent, and no New York accent, and the rest of his life story has zero confirmation, but it doesn’t really matter, since the essential facts about him are his auto-didacticism and his close actual connection with the working man. The True Believer attempts to construct a theory of irrational fanaticism as the basis for all mass movements, which for Hoffer means basically Christianity, Islam, Communism, and Nazism. -

Presidential Kin, Class, and Performance, 1789•fi2002

New England Journal of Public Policy Volume 18 | Issue 2 Article 4 3-21-2003 White House Inheritors and Climbers: Presidential Kin, Class, and Performance, 1789–2002 Garrison Nelson University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp Part of the President/Executive Department Commons, and the Social Influence and Political Communication Commons Recommended Citation Nelson, Garrison (2003) "White House Inheritors and Climbers: Presidential Kin, Class, and Performance, 1789–2002," New England Journal of Public Policy: Vol. 18: Iss. 2, Article 4. Available at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/nejpp/vol18/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Journal of Public Policy by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. White House Inheritors and Climbers White House Presidential Kin, Inheritors and Class, and Climbers Performance, 1789–2002 Garrison Nelson The 2000 presidential election that pitted Republican Texas Governor George W. Bush, the son of a former president against Democratic Vice President Albert Gore, Jr., the son of a former U.S. senator was a dramatic reminder that presi- dential politics in the United States is not an equal opportunity employer. In this article retrospective assessments of presidential performance are re- lated to social class and kinship connections for the forty-two presidents from George Washington to George W. Bush. Three separate evaluations of presiden- tial performance were used: the 1989 Murray-Blessing Survey; the widely cited 1996 New York Times poll prepared by Arthur M. -

The True Believer Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements 1St Edition Free Download

FREE THE TRUE BELIEVER THOUGHTS ON THE NATURE OF MASS MOVEMENTS 1ST EDITION PDF Eric Hoffer | 9780060505912 | | | | | The True Believer - Wikipedia The author of ten books, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in It is widely considered a classic. This book deals with some peculiarities common to all mass movements, be they religious movements, social revolutions or nationalist movements. It does not maintain that all movements are identical, but that they share certain essential characteristics which give them a family likeness. All mass movements generate in their adherents a readiness to die and a proclivity for united action; all of them, irrespective of the doctrine they preach and the program they project, breed fanaticism, enthusiasm, fervent hope, hatred and intolerance; all of them are capable of releasing a powerful flow of activity in certain departments of life; all of them demand blind faith and single-hearted allegiance …. The book passes no judgments, and expresses no preferences. It merely tries to explain… pp. Hoffer says that mass movements begin when discontented, frustrated, powerless people lose faith in existing The True Believer Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements 1st edition and demand change. The destitute are not usually converts to mass movements; they are too busy trying to survive to become engaged. Such people are resentful and blame others for their problems. Others include misfits, outcasts, adolescents, and sinners, as well as the ambitious, selfish, impotent, and bored. What all converts all share is the feeling that their lives are meaningless and worthless. A rising mass movement attracts and holds a following not by its doctrine and promises but by the refuge it offers from the anxieties, barrenness, and meaninglessness of an individual existence.